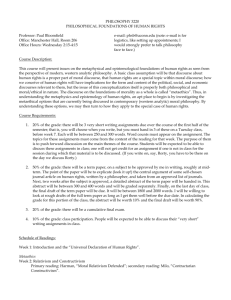

4.8 COPING WITH NIETZSCHE'S LEGACY: Rorty, Derrida, Gadamer

advertisement

HZT4UE – Theory of Knowledge UNIT 4: LANGUAGE 4.8 COPING WITH NIETZSCHE'S LEGACY: Rorty, Derrida, Gadamer I know my fate. One day my name will be associated with the memory of something tremendous—a crisis without equal on earth, the most profound collision of conscience, a decision that was conjured up against everything that had been believed, demanded, hallowed so far. I am no man, I am dynamite. — Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, "Why I Am a Destiny." For us who today read Nietzsche after Heidegger, Nietzsche symbolizes the end of metaphysics (the death not only of "God" but also, as a necessary consequence, of the human "subject"). Whether or not Nietzsche actually succeeded in "overcoming metaphysics"—by means of his inventive myths, his "fictions," of the Will to Power, the Uebermensch, and the Eternal Return—or whether, as Heidegger would have had it, he was simply the "last of the metaphysicians," his own "last man" in effect, is a question still awaiting an answer. What I wish to reflect on in this essay is the meaning of what has been and is going on in the wake of Nietzsche's deconstructive critique of the Tradition. Where do we stand, where can we stand when the very concept of "ground," the metaphysical concept par excellence, has been swept away? A quote from the literary critic Terry Eagleton might help to pinpoint the crucial cultural issue arising out of Nietzsche's all-out attack on the Tradition. Eagleton writes: We are now in the process of wakening from the nightmare of modernity, with its manipulative reason and fetish of the totality, into the laid-back ["joyful," as Nietzsche would say] pluralism of the postmodern, that heterogeneous range of life-styles and language games which has renounced the nostalgic urge to totalize and legitimate itself....Science and philosophy must jettison their grandiose metaphysical claims and view themselves more modestly as just another set of narratives. In other words, as a result of Nietzsche, what has been called into question in these postmodern times is that which has served always as the ultimate legitimation of the philosophical enterprise: the search for Truth, for Knowledge, for, that is to say, Science (Wissenschaft, episteme). i.e., the One (Universal), True Account of Things (Reality). The concept of a Science of Truth is a Platonic invention, but it underwent a new twist at the beginning of modern times with the emergence of mathematical, experimental science of the Galilean sort. Modern philosophy can be said to have begun when, bedazzled by this new development, philosophers took the new science as the supreme model of genuine, foundational knowledge. They were, ever afterwards, to labor in the shadow cast by this great Idol. Even the "free thinking," godless philosophers of late modernity continued to pay a sort of religious hommage to it. As Nietzsche remarked in the Genealogy of Morals, "They are far from being free spirits: for they still have faith in Page 1 of 9 truth." And as he went on to say: "It is still a metaphysical faith that underlies our faith in science—and we men of knowledge of today, we godless men and anti-metaphysicians, we, too, still derive our flame from the fire ignited by a faith millennia old, the Christian faith, which was also Plato's, that God is truth, that truth is divine." When at long last Nietzsche took to doing philosophy with a hammer, it was precisely this Idol that he sought to demolish. In other words, as Nietzsche would say, when the value of truth is called into question, everything becomes (mere) interpretation ("There is only a perspective seeing, only a perspective 'knowing'"). When the "real world" at last becomes a myth, a simulacrum, we are witnessing the death not only of Truth and of Science, but also of Philosophy itself. At least Philosophy with a capital P, as Rorty would say. What are we then left with? Is there anything to be found in Nietzsche's legacy ("Let us abolish the real world") other than the most abyssmal of nihilisms? What are we to do when there is no more Truth and no more Reality—and no more Philosophy (Science) to tell us what Truth and Reality really and truly are? How are we to cope with this situation which defines our postmodernity? Perhaps we could pick up some pointers by considering how three eminent thinkers of our times—Rorty, Derrida, Gadamer—have sought to cope with Nietzsche's legacy, each in his own quite distinctive way. Rorty Rorty, it must be admitted, has not had any great trouble knowing what to do after the end of Philosophy. Of the three thinkers I shall be considering, Rorty has been the least discomforted by the heavy burden of Nietzsche's legacy. Indeed, in the light-hearted joyfulness of his new-found philosophical innocence, he has wholeheartedly embraced Nietzsche's pronouncements about the demise of Truth. If he is anything at all, Rorty is a carefree, happy-go-lucky nihilist who is not about to let himself be bothered any more by the old concerns of philosophy. Nietzsche's word about the "death of God" seems to have been the liberating news he had been awaiting throughout all of the years of his exile in the arid waste lands of analytic philosophy. He tells us now that reading philosophy books is mostly a waste of time (it doesn't contribute to human solidarity): Who, he asks, was ever convinced in ways that matter by a philosophical argument? We ought to read novels instead, people like Nabokov and Orwell, Dickens and Proust. Rorty fully endorses Lyotard's claim that philosophical metanarratives are out, mininarratives are in. What counts is not to say something "truthful" but something "interesting," something "edifying." We should also change the conversation as much as possible, lest it become boring (we do this, according to Rorty, by continually inventing new "vocabularies," "simply by playing the new off against the old"). Not Socrates' "Don't tell a lie," but Johnny Carson's "Don't be boring" seems to have become Rorty's watchword. And indeed Rorty has many interesting, even "edifying," things to say. I have no doubt that his Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1980) has performed an extremely valuable service to the English-speaking philosophical community (to those, at least, who have lent it an attentive ear). Page 2 of 9 What is liberating and exhilarating about the book is the way in which it was able to open the eyes of so many people to the utter bankrupcy of traditional, foundationalist philosophizing. European philosophers (e.g., Derrida) had of course already said much the same thing, but Rorty's easy style of writing served to bring the message home with great éclat. What is announced here so effectively is the demise of modern philosophy, of, in other words, the whole epistemological project of modernity or what Rorty calls "epistemology centered philosophy." In Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature Rorty uses the term "hermeneutics," to designate this central attempt on the part of postmodern thinking to set aside epistemologically centered philosophy. This is a most fitting term since Gadamer himself has characterized his philosophizing—hermeneutics—as an attempt to overcome the modes of thought of "the epistemological era (l'ère de la théorie de la connaissance)." In his subsequent writings, however, Rorty tends to use the term "hermeneutics" less and less, perhaps due to the influence of Derrida, who quite erroneously has insinuated that hermeneutics remains attached to the old metaphysics of presence. But this, too, is fitting since in this book Rorty gives a hint of what is to come when he says that "hermeneutics is an expression of hope that the cultural space left by the demise of epistemology will not be filled". Unlike Gadamer who has sought, by means of hermeneutics, to provide an alternative, a postmodern option, to "epistemologically centered philosophy," Rorty does indeed leave us with a cultural void. This is precisely what makes Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature a "deeply disturbing" book. What indeed, we may ask, are the ultimate "consequences" of Rorty's postmodern pragmatism? I think they can fairly well be summed up in two words: relativism and nihilism. Rorty has, to be sure, protested the charge of relativism, but his responses are evasive and his arguments lack the power of conviction (which I suppose is only fitting in the case of someone who no longer believes in philosophical argumentation). We are inevitably condemned to relativism when, rejecting like Rorty the metaphysical notion of Truth, we reject the legitimacy of theory, which always seeks some form of universal validity. And, similarly, we find ourselves in a state of nihilism when, rejecting the metaphysical notion of Reality, we go on to assert as well that everyone's "truths" are merely their own private "fictions," when, that is, we equate fiction with mere semblance and deny it the power to recreate or refigure, and thus enhance, what is called "reality." Rorty says that in a post-Philosophical age the attempt to understand things (by means of philosophical theory) is passé. The important thing, he says, is to learn how to cope. Rorty obviously likes to view himself as a kind of social or culture critic, denouncing cruelty and promoting solidarity. One thing that flows from his postphilosophical stance, however, is the rejection of any form of universal theory (diverse cultures or "conceptual schemes" are simply "incommensurable"), and thus any form of philosophical, which is to say universal, critique; for this he would substitute a "de-theoreticized sense of community," in other words, compassionate feelings of a Rousseauian sort. Having thrown overboard the universalist claims of Enlightenment reason, the best Rorty can do when confronted with "cruelty" is to express his personal distaste for it by not admitting cruel people to his own comfy club of "we postmodernist bourgeois liberals," i.e., Page 3 of 9 "people who are more afraid of being cruel than of anything else." Letting it be known that they are not "one of us" is about as condemnatory as he can get. We may believe in something like human rights and the value of the individual, but if we are candid, we must admit that "this belief is caused by nothing deeper than contingent historical circumstance". What right do we have, therefore, to "impose" it on people in other cultures and historical circumstances? None, it would seem, since there are no "general principles," only historical narrations whose validity (if that's the proper word) is limited to a given community at a given time. It is hard to imagine what kind of argument Rorty could address to the violators of human rights in China, or any other country, other than to urge them to read George Orwell. I can in fact see how the ruling clique in China could well turn Rorty's anti-universalist, "frankly ethnocentric," stance to their own good use when they feel the urge to protest Western denunciations of their barbaric practices as so much interference in their "internal affairs": Who are we Westerners, we "bourgeois liberals", we non-Chinese, to tell them what to do anyhow? Rorty has deconstructed the metaphysical absolutism of the Tradition only to land himself in the quagmire of a quite traditional form of ethical relativism. Like (as some would say) Nietzsche himself, Rorty has not succeeded in "overcoming metaphysics"—although he has at least managed, willy-nilly, to find a way of coping with the nihilism which, as Nietzsche pointed out, tends inevitably to follow upon the overthrowing of metaphysics. Rorty's writings can be of value to those who no longer have any principled way of defending the notion of value. Derrida Derrida is one of Rorty's cultural heroes, and it is not hard to see why. As a fellow postnietzschean who also proclaims the demise of philosophy and the end of "man," Derrida has all the appearances of being a living incarnation of the Rortyan ideal of the nonchalant postphilosophical thinker, viz., the "kibitzer" and "all-purpose intellectual," the "intellectual dilettante." Derrida is clearly a child of Nietzsche's, an heir, as Rorty sees it, to Nietzsche's joyful wisdom who, beyond all metaphyscial seriousness, extols the playful "innocence of becoming." Like, you might say, the child idealized by Nietzsche who in his playfulness "constructs and destroys, all in innocence," who "builds towers of sand...at the seashore, piles them up and tramples them down...in innocent caprice." For Rorty, Derrida is the great postphilosophical prankster, the "ironist," the indefatigable turner-out of texts which are mercifully free from the burden of having to actually mean something (qui ne veulent rien dire, as Derrida himself would say), a superb fabricator of "private fantasies." A number of Derrida's writings, especially later ones such as Glas (which even Derrida scholars seem to have difficulty making sense of) would, on the face of it at least, seem to be nothing more than elaborate jokes, philosophy just for the fun (or pun) of it, a form of gleeful, uninhibited scribbling which, as Rorty says, seeks neither to demonstrate anything nor refute anybody. Compared to the up-tight analytic philosophers Rorty grew up with, Derrida is undoubtedly a delightful jokester. And yet there is a kind of seriousness to the Derridian enterprise that escapes Rorty's notice or, to be more precise, that Rorty prefers to ignore, to which he turns a blind eye. Page 4 of 9 Derrida may indeed be a postmodern gamester, but there is more to his work than "just gaming". It is of course true that Derrida is no more of a believer in the traditional metanarratives of philosophy than is Rorty and is thus, like him, a kind of postmodern agnostic who sets no store by philosophy's traditional claim to "knowledge" (scientia) and is in fact out to undermine it as best he can. In some ways Derrida is even less of a "philosopher" than Rorty, since he not only does not have a "position" to defend but does not even engage in arguments against various philosophical positons. What is referred to as "deconstruction" is not a set of theses or beliefs, not even loosely articulated ones like those of Rorty, but is simply, so to speak, a method, a way of reading texts, philosophical ones in particular. Actually, it is not even a "method," at least not in the modernist sense of the term, i.e., a set of explicit rules to be followed so as to arrive at certain positive results ("the truth"). This is why Derrida insists that what he is doing is not "hermeneutics," by which he means that his reading of texts does not aim at unconvering a hidden meaning in them. Derrida quite simply does not believe in meaning—a hopelessly metaphysical concept according to him. The task of deconstruction is in fact to show that philosophical texts do not mean what they seem to mean, do not mean what their authors wanted them to mean (what they "intended"), do not in fact have any "decidable" meaning at all. The aim of a deconstructive reading is to show how texts laying claim to knowledge are full of internal tensions and contradictions or antinomies which end up by subverting their stated goals and their own claims to truth. The purpose of a deconstructive reading of philosophical texts is frankly anti-Philosophical; it is aimed at showing how in every instance the attempt by traditional philosophers to use language in such a way as to get beyond language so as to arrive at some translinguistic, transcultural, transhistorical Truth— which language could then be said to "mirror," inevitably fails. Philosophers who aim at the Truth, at universal essences, cannot in fact escape the gravitational pull of a particular language. Philosophy's univocal concepts turn out to be nothing more than disguised metaphors of strictly local prominence and significance. There's no escaping the play of language. That is the "liberating and exhilarating" side to Derrida's work. But there is another side to it which, if not "deeply disturbing" (as in the case of Rorty), is, at the very least, disappointing. The trouble with deconstruction is that it does not seem to "go" anywhere. Unlike Rorty, Derrida realizes, as I mentioned before, that one cannot simply toss "metaphysics" out the window and be done with it once and for all. The work of deconstruction is serious and demanding, requiring "the skill of the tightrope walker, tripping the light fantastic on a world-wire over the abysss." Overcoming metaphysics is thus no easy matter; it is necessary, Derrida suggests, to lodge "oneself within the traditional conceptuality in order to destroy it." There is an honesty here that one does not find in Rorty who seems to believe that whenever it strikes our fancy we can change ourselves overnight by simply inventing new "vocabularies." That notwithstanding, having deconstructed metaphysics but unable to get beyond it, remaining, as he might say, "on the edge," Derrida is left, and leaves us, sitting in the rubble of this once magnificent monument to human pride and presumptuousness. This is perhaps why the later Derrida, who is much more to Rorty's liking, tends more and more to just horse Page 5 of 9 around, turning out texts whose philosophical significance, if any there be, is hard to detect but which are the aesthetic delight of lit crit audiences this side of the Atlantic. But even Derrida's earlier (Of Grammatology, (1965)), more "serious" works are disappointing. After having deconstructed metaphysics, we are left, in a way similar to Rorty, with an immense philosophical void, with, indeed, a kind of nihilism. Derrida seems to believe that, in the absence of metaphysical absolutes, of a "transcendental signified," all that remains is the ultimately meaningless play of words which refer not in any way to "reality" but only to more and more other words, in an endless drift, deferral, or dissemination of undecidable meaning (différence), words without end, an abyssmal labyrinth in which we are forever condemned to wander aimlessly about."There are only, everywhere," he says, "differences and traces of traces," nothing but "a play of traces or differance that has no sense." Or as Rorty says of his hero: "For Derrida, writing always leads to more writing, and more, and still more." libido scribendi, ad nauseum, as the Romans would have said (or "logorrhea," as Allan Megill says). Because (as Derrida rightly perceives) nothing means any one thing in particular, he concludes that in the last analysis nothing means anything at all. Gadamer Disregarding the standard (pre-postmodern) narrative ordering according to which, as Descartes insisted, one should always begin at the beginning, I turn to Gadamer last. Even though his work is earlier than both Derrida's and Rorty's, its significance is perhaps best understood when viewed in the light of his wayward progeny. It is, after all, a basic hermeneutical principle that we always understand backwards, après coup. As Gadamer himself has remarked: "All beginnings lie in the darkness, and what is more, they can be illuminated only in the light of what came later and from the perspective of what followed." When examined in the context of what I have said about Rorty and Derrida, Gadamer's hermeneutics may perhaps be seen to provide valuable suggestions for doing philosophy in a postnietzschean, postmodern age, ones that are not to be found in either Rorty or Derrida. If the writings of Rorty and Derrida can be said to be liberating, and if indeed the notion of liberation figures prominently in one way or another in what they have to say, the same is no less true of Gadamer's work. Indeed, Gadamer has no qualms about retelling one of the greatest metanarratives of all time, that of the progressive liberation of humankind. In the context (significantly enough perhaps) of a discussion of Hegel he writes: [T]here is no higher principle of reason than that of freedom. Thus the opinion of Hegel and thus our own opinion as well. No higher principle is thinkable than that of the freedom of all, and we understand actual history from the perspective of this principle: as the ever-to-be-renewed and the never-ending struggle for this freedom. One remarkable thing about this text is how it manages to reiterate most of those notions that postmodernists of a relativistic and nihilistic bent have felt obliged to discard, notions such as progress, humanity, reason (philosophy), and history. It would be all too Page 6 of 9 easy, on the basis of a pronouncement such as this, to attribute to Gadamer a residual— or-not-so-residual—attachment to the old ideas of Philosophy. Jack Caputo, a great admirer of Derrida's, does not hesitate to accuse Gadamer of being a "closet essentialist." Gadamer himself has protested Derrida's portrayal of him as "a lost sheep in the dried up pastures of metaphysics." What critics like Caputo fail to notice is for Gadamer, there is only one thing we can know for sure, and that is that any kind of Hegelian absolute is irremediably beyond our grasp. "Philosophical thinking," he writes," is not science at all....There is no claim of definitive knowledge, with the exception of one: the acknowledgement of the finitude of human being in itself." To acknowledge human finitude is to acknowledge that, for us at least (for any existing individual, as Kierkegaard would say), there can be no end to history—and thus no guaranteed, transcendenally sanctioned meaning to it (i.e., no science of history). All things considered, this is a fairly apt description of the difference between hermeneutics and deconstruction. One could sum up this difference by saying that whereas deconstruction undermines the traditional notions of "truth," "reality," and "knowledge," leaving nothing in their place (nihilism), hermeneutics has sought to work out a genuine understanding of these concepts. For hermeneutics, "truth" no longer signifies the "correspondence" of "mental states" to "objective" reality, and "meaning" is no longer conceived of as some sort of objective, initself state of affairs which merely awaits being "discovered" and "represented" by a mirroring mind. "Truth" and "meaning" refer instead to creative operations on the part of human understanding itself, which is always interpretive (never simply "representational"). Hermeneutical truth is inseparable from the interpretive process, and meaning, as hermeneutics understands it, is nothing other than what results from such a process, namely, the existential-practical transformation that occurs in the interpreting subject as a result of his or her active encounter with texts, other people, or "the world." Truth and meaning have nothing "objective" about them, in the modern, objectivistic sense of the term; they are integral aspects of the "event" of understanding itself, are inseparable from, as Gadamer would say, the "play" of understanding. In reconceptualizing truth and meaning in this way, hermeneutics thereby also reconceptualizes the pivotal notion of "knowledge." What is called "knowledge" is nothing other than the shared understanding that a community of inquirers comes to as a result of a free exchange of opinions. For Gadamer, understanding "is a process of communication." In reconceptualizing matters in this way, and in insisting on the "communicative" nature of human understanding, hermeneutics offers us something more than does deconstruction, i.e., something more than the mere cacophony of everyone's parodying, fanciful interpretations of things (the "private fantasies" of Derrida that Rorty speaks of). Accomplished though he be in exposing the "blind spots" in philosophical texts, there is in Derrida's own writings a rather curious and in any event very significant blind spot. If Page 7 of 9 Derrida rejects the notion of truth altogether, it is because he equates truth with representation. Gadamer breaks with this understanding of truth and proposes a quite different, genuinely postmodern conception of truth. Truth is not something simply to be discovered ("represented") but something to be made—through the exercise of communicative rationality. Truth is a practical concept. It is something that can exist only if we take responsibility for its existence. "Philosophy" is one name for the exercise of this kind of responsibility. In emphasizing the importance of common agreement and mutual understanding in what is called "knowledge," hermeneutics allows us to conceive of, and to strive to realize, a society which would be something more than a deconstructed Tower of Babel. Gadamer's dialogical view of understanding (as a communication process) provides the model for a social order based not on coercion or domination but on rational persuasion, the kind of tolerant and pluralist social order envisaged by the great rhetoricians and humanists of the past. That being said, Gadamer felt that the error of the Enlightenment was its 'prejudice against prejudices', ie. the refusal to acknowledge that the 'objective' rational scientific persona sought by the Enlightenment is always immersed in a subjective culture, language and tradition and therefore the understanding of ourselves as human beings can never be reduced to the positivistic methodologies of the natural sciences. Gadamer examined these and related issues in great detail in his enormously influential work, Truth and Method (1960). I might note as well that because hermeneutics, unlike deconstruction, contains quite definite implications for social behaviour, it promotes the exercise of critical reason. The function of hermeneutical criticism is to expose and denouce forms of socio-political organization which oppress and stifle the communicative process—fostering thereby the development of communities which dialogue . As both the theory and the practice of interpretive understanding, hermeneutics, Gadamer says, "may help us to gain our freedom in relation to everything that has taken us in unquestioningly." The hermeneutical enterprise is indeed, as Gadamer says, one of "translating the principle of freedom into reality." Madison, Gary Brent. Philosophy Today, (Winter 1991): 3-19. [From his forthcoming book, The Politics of Postmodernity: Essays in Applied Hermeneutics] Page 8 of 9 Questions on Nietzsche's Legacy 1. Three of Nietzsche's major ideas are Eternal Return, Zarathustra (or Superman), and the Will to Power. These ideas were discussed in class. Summarize each of them in your own words. What do you think about each of them? 2. Summarize, in your own words, the quote attributed to Terry Eagleton. 3. What is nihilism? For Nietzsche, nihilism is the result of what? 4. How does Rorty respond to Nietzsche's nihilism? Use the word 'edifying' in your answer. 5. What is a weakness of Rorty's pragmatic coping? 6. What commonality does Derrida have with Rorty? 7. How does Derrida use deconstruction? 8. What does the word différance signify for Derrida? 9. Gadamer is a little more optimistic about the demise of Philosophy than Derrida and Rorty. What does Gadamer value most highly? 10. What is the Enlightenment error? Explain. 11. What kind of society behaviour does Gadamer prescribe? Page 9 of 9