Slate

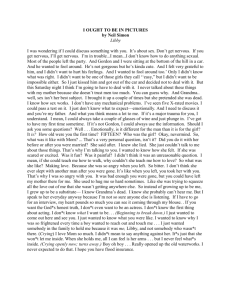

advertisement