Betta History

advertisement

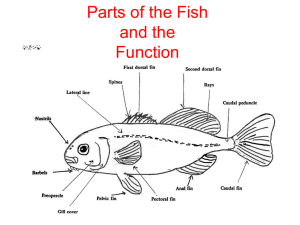

http://home.hiwaay.net/~keiper/bettastory.htm Rainbow-hued bettas have colorful history When a betta's rainbow hues catch your eye, it is easy to overlook the rich history that has brought aquarists the different varieties and color patterns available today. The Siamese Fighting Fish, Betta splendens, has a history as colorful as its flowing fins. The Siamese have possessed an interest in the betta, primarily for its fighting nature, for many centuries. The fish selected to fight were chosen for their pugnacious attitude rather than their looks. These fighters -- streamlined, short-finned, dirty greenish-brown fish -- bore little resemblance to the bettas of today. In 1840, the King of Siam presented several of his prized fighting fish to a friend of Theodor Cantor, and he, in turn, gave them to Cantor, a doctor in the Bengal Medical Service. Although these fish were more colorful than their earlier counterparts, their predominant colors of olive green, black and red still left much to be desired. The fin lengths also varied from specimen to specimen. In 1849, Cantor published an article on the fighting fish he called Macropodus pugnax, var. It was not until 1909 that C. Tate Regan reexamined this and noted that pugnax was already a distinct species. Since the fish had no scientific name, Regan named it Betta splendens, according to Gene Wolfsheimer, author of Enjoy the Fighting Fish of Siam. The German aquarists Arnold and Ahl explained that the first living fighters were introduced into Germany in 1896. They described these imports as short-finned fish with varied coloring. This same species did not arrive in the United States until 1910, according to Wolfsheimer. William T. Innes, famed American aquarist, explains that in the early days of the hobby, Betta splendens had a yellowish brown body with some touches of color and a few indistinct horizontal lines, moderately sized fins and a rounded tail. It was not until 1927 that the first brightly-hued, flowing-finned Siamese fighting fish arrived in the United States, according to Wolfsheimer. These fish were in a shipment consigned to Frank Locke of San Francisco. He noted both dark bodied and lighter cream colored variations. Thinking these light-bodied specimens were a new species, he named them Betta cambodia. But it soon became evident that this particular variant was only another of the many-hued forms of Betta splendens. Dr. Hugh M. Smith, renowned author of the Fresh Water Fishes of Siam or Thailand, made this observation concerning the Cambodian bettas. He believed these light-bodied fish originated in French Indochina in about 1900. According to Smith, the Siamese referred to them as "pla kat khmer" or Cambodian biting fish. To understand the colors and patterns bettas are bred to have, you must understand the layers of color involved. David Johnson, in his information on breeding and keeping bettas, explains that yellow is the bottommost color, then black, then red and finally blue. To get a yellow betta, you have to have one that has genes for non-red, non-blue and non-black. There are three types of blue: metallic blue, royal blue, and blue-green, with royal blue being the mixed form of the other two. Cambodian bettas are basically bettas with one body color and another fin color while butterfly bettas are Cambodians with two fin colors. Breeders developed golds out of a Cambodian-black cross. Some of the F1 fry were iridescent green with a sparkle of gold on the pectorals. The F2 fry yielded green and Cambodian fry with a golden shine on their bodies and fins. Through several generations of breeding, the red was removed and the gold enhanced. Tutweiler founded the Tutweiler Butterfly, a Cambodian with fins divided between white and red, but this strain was never fixed. Jay C. Niel of Michigan founded the butterflies we have today. He managed to raise cambodian-red-white fry, thus giving birth to the butterfly bettas. True butterflies should have color at the tips of the unpaired fins and not closest to the body. The marbles have their roots in the Indiana State Prison, where they were developed by Orville Gulley, an inmate. Walt Maurus, founder of Bettas Unlimited, bought some of Gulley's bettas. Gulley didn't pursue the marble betta, but several people who acquired his fish kept the line going. Dr. Gene Lucas, betta specialist, developed opaque white bettas around 1960. Other traits have been fixed then lost and found again. Paul Kirtley re-created doubletail blacks in the '80s, and they have been around ever since. The fixing of color strains and the doubletail traits are largely due to the International Betta Congress and its members. Paul Ogles, who has worked with long-finned domestic bettas for many years, explained that it is safe to say that yellows, marbles, blacks and most doubletails exist today because there are show classes for them within the IBC. Betta splendens' flowing fins give them a distinct look unmatched by other tropicals. The pelvic or ventral fins are found in front of the anus. They are colorful and long, and contain 5 rays. The dorsal fin, found on the betta's back, is usually very long. If the betta is a doubletail, or carries the doubletail gene, the dorsal fin will be about twice as wide as a regular betta's 6 rays. The caudal peduncle is the rear part of the fish's body to which the tail fin, or caudal fin, is attached. In the case of a double-tailed betta, sometimes the caudal peduncle is visibly separated near where the tail fin itself is attached, as if the fish literally had two separate tails, according to Terri Gianola, manager of the Bettas WebRing on the World Wide Web. The caudal fin is generally wide and flowing in the male betta splendens, often falling as far as the bottom of the anal fin. The caudal fin of the doubletail is literally split into two separate tail fins. If the separation begins in the caudal peduncle, these fish have two separate tails. The anal fin, located on the bottom of the fish, behind its anus, runs the length of the fish from its anus to its tail. It consists of 25 rays. The fins closest to the alert eyes and upturned lips of the male betta's face are some of the most ordinary. These pectoral fins, found behind the gills on the sides of the fish, often lack color, while other bettas have partial or good coloring of the pectoral fins. These fins should have 12 rays. Bettas are not limited to the species splendens. The different species differ in body shape, fin length and aggressiveness. The Betta imbellis, or "peaceful betta," identified by Ladiges in 1975, has shorter fins but still exhibits bright colors. The males can be kept together and will attempt mock fights, but with little or no damage resulting. The short-finned Betta coccina is a timid fish, while the Betta brederi is a semi-agressive mouthbreeder. The male Betta pugnax also mouthbroods the eggs, and this species can be kept in a community tank in pairs. The male Betta splendens tends to his eggs and young in a beautifully built nest of bubbles at the water's surface. Regardless of the species, Bettas are anabantids, that is, they have the ability to breathe atmospheric air using a special organ called the labyrinth. Bibliography Gianola, Terri. Bettas and Spawning. http://members.aol.com/terrig2/bettas.htm, 1997. Johnson, David. The Betta FAQ: Breeding and Keeping Bettas. http://www.starpoint.net/dave/betfaq.html, 1996. Lucas, Gene A. Siamese Fighting Fish yearBOOK. Tropical Fish Hobbyist, Neptune, New Jersey. (No date listed) Marus, Walt. Bettas: A Complete Introduction. Tropical Fish Hobbyist, 1987. Ogles, Paul. Email interview. 1997. Wolfsheimer, Gene. Earl Schdeider, Editor. Enjoy the Fighting Fish From Siam. The Pet Library LTD, New York, New York. (No date available) Published in Tropical Fish Hobbyist February, 1998 Written By Bethany Waldrop Keiper Do not copy or reproduce without permission of TFH.