Comfort Women - Language Resource Center

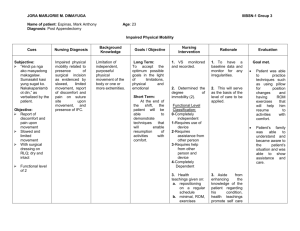

The Comfort Women: Controversy, Culture, and Context

Jacqueline Pak and Jinhee Kim

When the dismaying reality of comfort women as Japanese military sex slaves was initially revealed in 1991 in Korea, it inevitably caused deep stir and profound shock.

Much began with the heroic efforts of a single individual, former professor Yun Jeongok of women’s studies at Ewha Women’s University, a petite, quiet and self-effacing but persevering woman. She vowed to inform the world about the historical reality and existence of cruel suffering of Korean comfort women whom she remarked belonged to her own generation and thus it was her responsibility to tell the world about it. Whether it was due to her “survivor’s guilt” or not, we have much to thank for her act of courage and commitment.

With escalated activism on comfort women in the late 1980s, Yun Jeongok became the founding mother of “The Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military

Sexual Slavery by Japan”, or Han’guk jeongsindae munje daechaek hyopuihoe

.

Established in 1990 with other academics, leaders, and activists, the organization is often known by its abbreviated name, Jeong-dae-hyop . The original name and spirit of the organization can be more broadly translated as “A conference association to consult, address, respond, or offer counter-measure to the problem of Korean spirit girls.”1 A breakthrough moment of the comfort women movement and controversy was the coming-out by Kim Haksoon, the former Korean comfort woman, in 1991. She had been persuaded by Yun Jeongok over time to announce and declare to the public about the

1

human atrocities that she and other Korean comfort women suffered by the Japanese military.

Yet, almost a decade prior to these developments, a fictional series on a daily, a novel, a television drama and documentaries on comfort women had appeared in Korean language from the early 1980s to the late 1990s. In fact, from the early 1980s, the Korean public became aware of the possible historical reality of comfort women, though it will be confirmed by survivor’s accounts only later. It is intriguing to delineate the nature and context of the early embryonic novels, drama series, and documentaries on comfort women as cultural products which contributed to the formation of public discourse in

Korea and beyond. In this essay, I attempt to broadly portray the milieu that gave rise to the comfort women controversy and movement from the 1980s to the present through some of the cultural representations on comfort women. Jinhee Kim provides close reviews of three English-language novels by Therese Park, A Gift of the Emperor (1997),

Nora Okja Keller, The Comfort Woman (1997), and Changrae Lee, A Gesture Life (1999), related to the theme of comfort women. She thus juxtaposes the fictional accounts of a first-generation Korean-American woman writer Therese Park, a biracial Korean-

American woman author Nora Okja Keller, and a second-generation Korean-American male writer Changrae Lee. Due to limited space and time, not all cultural representations and literary or film products on comfort women can be mentioned or included here.

The aim or motivation of the essay was to discern the unfolding momentum and process of consciousness-raising of the comfort women issue in Korea and abroad by cultural products, osmosis, and means. How was the shocking yet sensationalistic problem of comfort women, hidden under silence and shame for so long, begin to be

2

introduced to the public in Korea by cultural, literary, or media instruments? How was the comfort women controversy and the movement buttressed by the growing public discourse in terms of academic, intellectual and cultural representations, which were often transnational and diasporic in nature? As the comfort women discourse unfolded in

Korea and abroad, how has the comfort women phenomenon as controversy and movement been represented and defined? How was the disturbing historical knowledge and phenomenon of Japanese military sex slaves been culturally represented, popularly distributed, and publicly ingested? In what ways did the comfort women problem become part and parcel of shared national and transnational history, knowledge and discourse? Perhaps, not all the questions can be adequately answered here, but an effort is made to explore relevant facets of the problematics and pragmatics of the comfort women controversy and movement.

1. Eye of the Dawn: A Colonial Drama, 1981-1992

A television drama based on a serial fiction by a Korean writer Kim Seongjong, “Eye of the Dawn” appeared in a Korean daily in 1981.

2 This was perhaps the first fiction to address the harrowing and disturbing reality of comfort women during the Japanese colonial rule. As a serial drama to commemorate the thirty-year anniversary of MBC, a

Korea’s major television network station, “Eye of the Dawn” (or a.k.a. “Burning Dawn”) was broadcast from October 7, 1991 to 1992, in thirty-six episodes. The highly successful and provocative television drama series was directed by Kim Jonghak with the script written by Song Jina.

Of the same title by the writer, “Eye of the Dawn” is a narrative of three young

3

Korean protagonists caught in the maelstrom of the nation’s modern history. Spanning from the colonial period to the Korean War, the series brought attention to Japanese war crimes, especially the comfort women, and the subsequent tragedies wrought by Korea’s ideological divisions. It also raised the unresolved history problems of Japanese colonialism and imperialism in East Asia, such as the Nanking massacre, “731 Unit” of

Japanese military which performed medical and chemical experiments on live Koreans and Chinese subjects, and the legacy of pro-Japanese collaborators in post-liberation

Korean history. For example, a Korean named Suzuki who served as a policeman to torture Koreans for Japanese continued to serve in such a role after the liberation in 1945.

The story of drama concerns three protagonists, Jang Harim, Choe Daechi, and

Yun Yeo-ok, caught in the tumults of colonial Japan’s militaristic drive to the subsequent chaotic national liberation to the civil war which mercilessly sacrificed, uprooted, and scattered loves and lives. With strong script, acting, directing, and production as well as a poignantly lingering theme song, the television drama series became a huge hit. With a cast of more than 270 as well as more than 27,000 extras, location shoots in the

Philippines and China (which at the time was unprecedented as South Korea had yet to normalize relations with its communist neighbor), three-years in the making, “Eye of the

Dawn” was a huge critical and popular success.

Beginning with a premise of the main protagonist, Yun Yeo-ok, who was forced to become a comfort woman during the colonial era, this drama series was the first on

Korean television to introduce and problematize the issue of the Korean sex slaves for the

Japanese military. Now well-known but then promising actors Choi Jae Sung and Park

Sang Won assumed the leading roles. A young, beautiful, and versatile actress Chae Sira

4

played the role of Yun Yeo-ok with high acclaim. Fresh-faced Chae debuted at sixteen in a commercial and achieved a star status in this wildly popular television drama. Though it was in the early 1990s, fans still remember the actress foremost as the innocent and tragic heroine as a comfort woman in “Eye of the Dawn”.

“Eye of the Dawn” pioneered the “special project” template for networks in the future and paved the way for a landmark television syndrome Sandglass or Morae Sigae

(1995), by Kim Jonghak and Song Jina. It dealt for the first time in a television drama with what had been political taboo subjects in Korea -- the Kwangju massacre and the shadowy underworld and corruption of the Park Chunghee era -- for the then budding and rival network, SBS. The drama won many top awards of the industry in Korea. The following is a list of the awards it won: Baeksang Awards (1992) - Daesang (Grand Prize),

Best Drama, Best Director, Best Actor (Choi Jae Sung), Best Actress (Chae Si Ra);

Korean Broadcasting Awards (1992) - Best Drama, Best Producer; and Producers

Association Awards (1993) - Best Drama.

2. Spirit Girls to Sex Slaves: A Nascent Novel, 1982

A prolific Korean woman writer Yun Jeongmo is widely known, especially among the pro-democracy and anti-American student protesters in the 1980s. She is best known for her work, Rope, or Koppi, published in 1988, which was considered a must-read for all entering college freshman. The Korean book title, koppi , suggests a rough twined cord that binds or kinks. It also implies a form of enslavement as in the case of a cow who works life-long for a farmer or a fateful tie and inescapable connectedness.

Published in 1982, Your Mother was a Korean Comfort Woman ( Emi Irumun

5

Josenppi yeotta) by Yun Jeongmo was one of the earliest novels or fictional works on the subject of Japanese military sex slaves in Korean language. It certainly appears to be the first book on comfort women by a Korean woman writer. A more literal translation of the title of the novel is “Your Mother’s Name was Josenppi

”.

Not a sweeping historical melodrama in the way that the fictionalized television series, Eye of the Dawn, was, the book is a haunting story of a Korean woman who had been a comfort woman for the

Japanese military whose life was filled with han of sadness, bitterness, and pain. It is a more intimate narrative of a Korean mother and her relationship with her daughter. This novel was one of the earliest to addresses and exposes the issue of comfort women, and importantly foreshadowed the rise of comfort women activism in Korea and controversy in East Asia and the world.

Actually, I came to befriend the writer Yun Jeongmo and her family while I was a doctoral student in London in 1995-1999. I cannot exactly recall when I first met her.

Over time, I saw her on numerous occasions with mutual friends with whom we socialized in London. A warm, thoughtful, and humane person, the writer gave me a copy of the book and inquired whether I could perhaps find time to translate her work into

English. I regret that I never quite found the time. Nonetheless, her effort to write and publish a book on comfort women is appreciated all the more in retrospect. In 1997, after fifteen years since its first publication, a reprint edition of the book appeared. Here, the author edited and improved the work and added illustrations by artist Yi Kyongsin. The book was translated into Japanese.

In her novel, Yun Jeongmo refers to the comfort women as jeongsindae , or “spirit girls”, in her book. Her work shows how the terms have evolved -- from the “spirit girls”

6

in earlier works to the more widely used euphemism of “comfort women” to the current circulation of more direct and explicit, “military sex slaves” -- over the past decades with growing awareness and consciousness-raising of the issue domestically and globally. The history of suffering of Korean women is not in past tense. To the extent that the Korean comfort women have not yet received official apology and compensation from the

Japanese government, it is very much a continuing problem of the present. This book also alerts us to this fact of historical responsibility and reflection. From 1968 to 2005, Yun

Jeongmo wrote nineteen books, including this work on comfort women.

3. Grandmother Trilogy: The Comfort Women Documentaries, 1995-1999

A remarkable feat of cultural production concerning the Korean comfort women in the

1990s is the documentary tilogy, “Grandmother”, or Halmoni. With an activist’s sensibility and purposefulness, it is a documentary series on the plight of comfort women by a Korean woman director Byun Youngjoo, created during the years of 1995-1999. Her documentary trilogy is composed of The Murmuring (Nateun moksori I) (1995), Habitual

Sadness (Nateun moksori II) (1997) and My Own Breathing (Sumgyol) (1999) which deal with the lives of comfort women who were forced into sexual slavery for the soldiers of the Japanese empire during World War II.

By 1995, the comfort women stories had become more widely known by the

Korean public. The special feature of Byun’s documentaries is not only her highly intimate esthetic style which dealt with extremely painful and difficult subject but also that she purposefully made the comfort women “familial” and “familiar” by evoking the grandmotherliness of the comfort women for all Koreans. She made the gut-wrenching

7

historical pain of comfort women for all Koreans to be shared in the most close-up familial domain, as if they were all our own grandmothers to us. The reality of comfort women, in fact, could have happened to anybody and anybody’s grandmother in Korea or other parts of the world affected by Japanese colonialism, militarism, and imperialism.

The fact of horrible sexual shame and stigma of the comfort women, in this way, could be sympathized, empathized, and desexualized. Moreover, in the close-knit clan and family culture and values of Korea, the individual and collective han of past history can be exorcised, if it belonged to one’s very own grandmother.

Through the documentaries, Byun lets us know and open our eyes to the fact that the comfort women could have been just as easily anyone’s grandmother. Not only by their age, the comfort women were old and growing old. And many of them were dying each day due to old age and illness. The remaining Korean comfort women were indeed

“grandmothers” in every sense of the word. According to an interview with Byun

Youngjoo by Adam Hartzell, her documentary The Murmuring was the first documentary to receive a theatre release in South Korea. Byun received critical praise for her aesthetic approach within these documentaries, along with her efforts to obtain redress from the

Japanese government for these women.

Most recently in 2008 in Korea, I have seen Byun as one of three film directorcommentators on a culture program on television which discusses Korean and other films,

“Cinema Heaven” (Cinema Cheonguk, after the famous Italian film

Cinema Paradiso ). A mannish-looking feminist, Byun often displays and employs her formidable perception, intelligence, and talent as a film director and commentator in the program. She is often enthusiastic with her concerns about the esthetic, narrative, and art of her own

8

filmmaking, and the new direction, course, and future of the Korean films.

Byun Youngjoo studied law at Ewha Women’s University and film at Chungang

University. She is presently the head of Vista, a documentary film production group. She made her directorial debut in 1993 with a video, “A Woman-being in Asia”, which documented the problem of “geisha tour” on the Cheju Island. While shooting this film, she met a woman prostituting to pay for her mother’s medical care, who suffered from the experiences as a comfort woman during World War II. Realizing that the issue was still affecting the lives of Korean women today, she set out to film, The Murmuring , the first of the Grandmother Trilogy. Byun Youngjoo worked with the comfort women for two years for her film, The Murmuring , which was screened at the Amnesty International

Film Festival in 1996.

The “Sharing House”, or Nanum ui jip, for comfort women provided the setting for Habitual Sadness , the second part of her Grandmother Trilogy showing the enduring wounds but strong spirit of the former comfort women. About her filming the documentary, Byun remarked: “During our time together, the [comfort women] slowly grew more comfortable and eventually even bold in front of the camera. As I watched them change, I felt as much joy as sadness, a habitual sadness that is always weighing on our lives,” said the director.

Habitual Sadness was a major success in South Korea and a hit at the Hong Kong Film Festival. Byun also stated that, “The victims do not look like they are weak. They look powerful. I think that is the special thing of my documentary.”

The director also noted: “What could be more frightening to a person who suddenly reveals herself to the world after fifty years of shame and silence, than to have people forget that determination, as if to tell you not to dare dream that all your hard-found

9

courage could change the world? Myself, I wanted only to express one thing: Let us not forget. We cannot forget. It is with these words of resolution that I repay what these women have helped me learn over the last five years.”

In the third documentary of her triptych, My Own Breathing , Byun explores the lives of Yi Yongsoo, who now lives in Daegu, was sixteen when she was captured by the

Japanese army as a sex slave to Taiwan, where she spent three years during World War II.

She is now energetically engaged in activities to bring justice for and receive compensation from those responsible for the crimes. While comforting fellow victims, who are worn out mentally and physically, she convinces them to give testimony in order to keep the memory alive. Kim Yoonshim, who recently won the Cheon Taeil Literary

Award for her writing based on her diary, was thirteen when she was taken to Harbin,

China. When she found out that her daughter was born with a hearing disability due to the syphilis she contracted at that time, she left home secretly and raised her daughter by herself. Despite the fact that she takes part in a demonstration every Wednesday and gives testimony around the country, to this day she is still unable to tell her daughter about her past.

In the director’s statement, Byun remarked: “In the five years that have passed since I began work on my two previous films on Japanese military comfort women, five of the women who appeared in those films have died. I complete this third film, My Own

Breathing , then, with a sense of grief and condolence. In those other two films,

Murmuring (1995) and Habitual Sadness (1997), the main space shown was the alternative living cooperative, the Sharing House. This time I asked for the testimony of other halmoni who spoke of past and present life among family and neighbors. The film

10

is divided into two parts to point out that these halmoni express themselves in two ways.

In the first part, a victim asks questions of other victims. But a comfort woman who does not particularly wish to recall excruciating connections to the past asks not to know, but rather to preserve memory. Eventually, the interviews create a dialogue, a perfect replica of history, a past into which the present cannot intervene. If the first part of the film is composed of the protective gaze of the camera, in the second half, the questions shift to the present, where my own role emerges. How do their pasts and my present confront each other? How is our time different and how is it the same? To me, making this film was to have a dialogue with these halmoni who face my camera, to face yet another death.

4. Nanjing Massacre and Comfort Women, 1995-2007

One of the earliest fictions in English that dealt with Nanjing massacre and comfort women is by Paul West, The Tent of Orange Mist (1995). A highly stylistic work filled with strong ambience and nuance of words yet also with terror of the situation, the novel was short-listed for National Book Critics Circle Fiction Award. On the book jacket, the novel is introduced as follows: “Paul West deftly illuminates the plight of intellectuals and artists during the Japanese occupation of China in this story of a young woman who must transform herself completely in order to survive. Scald Ibis, the properly-reared daughter of a Chinese scholar, is forced to work as a prostitute in a bordello as she changes slowly and painfully from girl to woman. When her father reappears in her life, she must deal with his inner demons as well as her own.” From the Library Journal , an excerpt of the review describes as follows: Set in China during the Japanese invasion of

11

the mid-1930s, this new novel by West, a writer Vance Bourjaily once called “our finest living stylist in English,” is both moving and intriguing.

Paul West, born in 1930, is a British-born American poet and novelist with twenty-four novels and three books of poetry. He has also written autobiography and nonfiction, and has won several major literary awards. Currently, he resides in upstate

New York with his wife Diane Ackerman, a writer, poet, and naturalist. He studied at

Oxford and Columbia University. With an eclectic style, he is a prolific writer on the human condition. The recurrent themes in his works include psychic abuse, failed relationships, and societal inadequacy, with a strong sense of self-discovery and survival.

In 1997, a best-selling non-fiction book by Iris Chang, Rape of Nanking: The

Forgotten Holocaust of World War II , caused quite a stir worldwide. Becoming a subject of international controversy, the book received acclaim by the public but also criticism by academics who observed Chang’s lack of professional and critical training as a historian in dealing with the documents and sources. Among other raw materials, Chang's research was aided by the finding of the diaries of German John Rabe, who had been called the

“Schindler of Nanking”, and an American woman missionary Minnie Vautrin. They both saved many Chinese lives in the Nanking safety zone, an area which protected Chinese civilians during the Nanjing massacre.

Her work importantly addressed the close causal and historical link between

Japanese military’s Nanjing massacre and the subsequent institutionalization of comfort women system by the Japanese government. Despite the shortcomings of scholarship,

Chang’s book also allowed to frame the discourse of Japan’s historical atrocities in a

12

broader rubric, as she referred to the Nanking massacre and other brutalities of Japanese imperialism and colonialism as the “East Asian holocaust”. Chang’s book was turned into

Nanking , a 2007 documentary about the Nanjing massacre, by Ted Leonsis who funded and produced the project. Chang related difficulties of translating her book on Nanjing massacre into Japanese to introduce to the Japanese public. She admitted receiving death threats from the Japanese right-wing. While working on another book, she committed suicide.

Two years before Chang’s book appeared, Christine Choy created one of the earlier documentaries in English in 1995 on the subject of Nanjing massacre and the comfort women, In the Name of the Emperor .

Nearly a dozen documentaries to her credit,

Choy is best-known for an Oscar-nominated Who Killed Vincent Chin ? (1988). This documentary investigated the death of a Chinese man beaten by a laid-off auto worker who thought Chin was Japanese, in a milieu of growing Japanese auto imports into

America. The 1988 film on an Asian-American has been described as follows. “It is

1982 in Detroit, a city plunged into recession by the advances of Japanese corporations. A

Chinese-American named Vincent Chin is mistaken as Japanese by Ebens, just laid off from an auto plant, and is beaten to death. The light sentence is completely out of balance with the injustice of the murder and sparks a large-scale protest movement. This work pursues the truth within the incident, intertweaving news footage with testimony from relatives and witnesses.”

Born in 1954 in Shanghai, Choy’s background is defined as a Chinese or Chinese-

American woman filmmaker. Yet, it has also been written in a website that she is a half

13

Korean and a half Chinese as an Asian-American. Her documentary in 1991, Homes

Apart: Korea , dealt with the ongoing pains and suffering of divided Korean families. She received a master’s degree in architecture from Columbia University and directing certificate from the American Film Institute. She taught at New York University, Yale,

Cornell, and SUNY Buffalo. She received Guggenheim and Rockefeller fellowships. Her works include Mississippi Triangle (1982-83), Best Hotel on Skid Row (1990), The Shot

Heard Round the World (1996-97), and Ha Ha Shanghai (2001).

5. A Gift of the Emperor, 1997

It is a compelling story about a young Korean woman’s traumatic experience as a comfort woman during World War II. The main protagonist, Soonah, is shipped to a horrifying land of deceit, cruelty and torture. Through the perspective of Soonah abducted from her village and forced into a comfort woman amidst the bomb-dropping atmosphere of World

War II. Therese Park, a Korean-American woman writer, vividly describes the brutalities encountered by her protagonist as a sex slave for Japanese soldiers. In addition to the representation of the harsh conditions that the war produced, this novel also artfully depicts and analyzes the transformation of the young protagonist who embodies the victory of the human spirit over adversity.

For the novel, the author displays a highly accessible, easy, and straightforward narrative style. An uncanny ability of the author to draw the readers to empathize and identify with the narrator is an alluring charm of the novel. Vivid details of Soonah’s life, beginning with her abduction into the Japanese army to her realization of her enslavement as a comfort woman to her ensuing escape from the comfort station, are

14

painted with emotion, stirring a resonant cord with the readers. Whether it is her heartwrenching protest against her sexual slavery in the Japanese army or her bitter anger after the Japanese emperor Hirohito finally surrenders, the readers have no problems in experiencing the depth of emotions embedded in these events. The novel offers a great deal of visual information about the malevolent nature and monstrosity of human beings.

As the story unfolds, the readers gradually come to recognize the changes that

Soonah undergoes both in her beliefs and convictions. The lives of her family were ruined by Japanese colonial oppression and the war. Soonah’s brother was recruited by the Japanese to fight for the Japanese army; her father was beaten and murdered for suspicion of being an underground Korean patriot; and a Japanese officer raped her mother in front of her. As if witnessing the cold-blooded murder of her father and rape of her mother by Japanese are not cruel enough, Soonah is later forced to joint the military effort as one of the vulnerable Josenjin girls. The events beyond her control force her to mature too quickly into an adult, but not without anger and resentment. The novel thus becomes a story of an individual seeking to survive in the face of adversity.

From the outset of the novel, we observe Soonah’s amazing courage. As a comfort woman, she is ravaged time after time. She contemplates suicide, like the actual testimonies of numerous comfort women. Forced to serve the Japanese soldiers in repulsive manners and immersed in grueling and savage atmosphere on a ship, Soonah confronts the tragic and dreadful reality of her life. Many Koran girls were actually taken away from their home as comfort women for the Japanese military beginning in 1938.

Young Korean girls were told that they were gifts chosen by the Japanese emperor to comfort the Japanese soldiers who were fighting the war. As gifts of the emperor, these

15

comfort women were to serve the Japanese imperial nation as virtual sex machines for the military.

Initially, because of her identity as a sex slave, Soonah falls into self-denials, feeling that she deserves nothing of importance or joy in life. Soonah also had difficulty conceiving or finding love because she felt that she is unclean and undeserving. For this very reason, she finds the romantic pursuits of her friend Ayako repulsive and outrageous.

But Soonah is ultimately able to find her love despite the horror of her obligation as a sex slave through the love of Sadamu, a Japanese soldier, who teaches her to respect herself.

Soonah slowly comes to a realization that her enslavement is not her fault at all. She also comes to recognize that Japanese individuals cannot be judged collectively. Finally, she gathers enough courage and compassion that hate in her heart only brings misery The readers notice Soonah’s transition from a vengeful young girl to a mature young woman who transcends hatred and resentment by opening her heart to the power of forgiveness.

Emerging from a young seventeen-year-old girl violated by the Japanese soldiers,

Soonah begins to find a new footing for herself through love. With the love of an unexpected companion and her newfound respect for herself, Soonah is able to overcome her difficulties. Soonah’s romance with Sadamu brings an interesting twist, as the novel takes Soonah to an uncharted path of life: she becomes a woman of audacity and inner strength. By closing the chapter of her life smeared by a tragic memory, Soonah is now resolved to move on with strength and endurance. While the book becomes a vivid account of the journey that Soonah endures until the end of World War II, the details of her love and escape from the island are quite adventurous and thrilling.

Though the story may seem a little farfetched at times, such as the escape to a

16

deserted island where Soonah and Sadamu live for months on mangos and coconuts, the novel still creates a believable plot. The escape appears a little bit too romantic for such a war-ravaged time but it adds fresh air to the novel. Soonah and Sadamu flee to a small yet uninhabited island in the Philippines. They are eventually rescued by an American ship. Soonah is then sent to Hawaii, while Sadamu, a Japanese journalist, is used as a spy for counter-intelligence by American military in the Philippines. His identity is soon divulged and is eventually killed by a double agent.

One of the most unique facets of the novel is the representation of Japan. In most stories pertaining to Korea and Japan relations, especially concerning comfort women, the strident antagonist is Japan. For decades without apology and compensation in the post-war era, Japanese government has been compared to the Nazis of the East, in the

East Asian version of Holocaust. Here, Soonah’s love for Sademu perhaps paints a different picture. The juxtaposition of Samadu to the Japanese soldiers offers a thoughtprovoking portrayal. The Christian humanism of the work indeed offers a multidimensional portrayal of Japan and Japanese people.

Violence, although powerfully moving, is not graphic or explicitly emphasized in the novel. The author seems to be far more concerned with the ethnocentric view of the superior over the inferior, or the victor over the vanquished. Such a view colors the account of the past and present circumstances. In this sense, it is not only a war novel but also a love story, which solicits historical remorse for comfort women by Japan and questions imperialist ideology of Japan.

The novel gradually focuses on the adventure of the main character fighting a battle within herself against the background of the actual war. She possesses strength to

17

live and overcomes the impossible and loves a man. Sadamu is a man of sincerity. And she is able to learn to live and realize that she too is worthy of being loved. Just as there are evil people, as the malevolent sergeant character, there are also people who are noble and genuine as Sadamu. A religious or spiritually redemptive aspect to the novel is that there are many times when Soonah is so angry that she almost plans revenge toward

Japanese. Yet, she always chooses to forgive the enemy. Perhaps, this is related to the fact that her murdered father is a priest, or that she believes deeply that even some of the horrible Japanese soldiers could be or should be forgiven.

As a first-generation Korean-American, Park incorporates Japanese-American characters to show the different views compared to the native Korean and Japanese characters. She also offers a more introspective view of the life of a comfort woman.

She is able to explore the day-to-day accounts of these women to demonstrate who they were and how they lived. She depicts how they were taken away from their families and allows the reader to trace the life of a comfort woman. Through the eyes and sensibilities of a young Korean school girl, the work provides a rare gaze into the world of sexual slavery and cruelties of war time.

For possible problems of the book, some have challenged the verisimilitude of the novel. For instance, it has been pointed out that the portrayal of comfort women in the work was inaccurate as it was tainted by the author’s imagination. It seems to me that she has done research on the topic of comfort women, but the ways in which she documented bad occurrences one after another made it seem not realistic. It is also unlikely that Soonah was able to escape from the comfort station without getting caught; she and Sadamu survived on the deserted island for so long; and an American ship

18

eventually picked them up. I also thought that the book compressed the events too much within the first twenty-four pages. In fact, just about everything terrible that could possible happen to a human being did happen to Soonah in these early pages. The ending was also abrupt and did not close well. Perhaps, this was done purposefully so that the author could lead the readers to wonder about the novel’s sequel, which is forthcoming.

6. Comfort Woman, 1997

What if your own mother had been a sex slave to Japanese soldiers during the World War

II? Can you imagine your mother going days without eating or bathing and wandering around the city? Can you imagine your mother singing and dancing in a manner only the ghosts could recognize? Can you imagine living in constant fear of losing your mother to a supernatural force? However unappealing they may sound, all of these scenarios are put together to create the unflinching fictional reality in which the character Beccah finds herself in Nora Okja Keller’s first novel,

Comfort Woman (Penguin, 1997).

Reminiscent of Chinese American author Amy Tan’s much celebrated Joy Luck

Club in its theme and tenor, Comfort Woman is, in essence, a story about a troubled love between Korean-born mother, Akiko, and her American-born daughter Beccah. Weaving together the Korean past and the American present through intimate accounts of Korean history, folklore, and shamanism, the novel also illuminates the struggles of Korean immigrants in their adopted country. Raised by a single mother on a forlorn edge of

Honolulu, Beccah is confronted by the alien yet overwhelming immediacy of Korean culture which her mother cannot escape. At the same time, she is challenged by the harsh way of life introduced to her by her father’s America--a journey all too common for many

19

Koreans in America.

While Beccah was growing up, her mother Akiko was a mystery to her. Akiko was Korean but went by her Japanese name. She worked at a restaurant but ran her own business at home. In addition to telling fortunes for people, she would often fall under mysterious spells, disappear into strange trances, and speak to spirits. Fearing that someone would come to take her mother away for her madness, Beccah would lock the door before leaving for school. She brought home half of her lunch from school to ease her mother’s hunger. Although Beccah was torn between love and embarrassment for her mother, she prayed that no one would take her mother away from her.

As Beccah struggled to keep her mother unharmed from spirits as well as the ridicule of her neighbors, she often retreated into her own world. As a teenager, she used to imagine that the Julie Andrews character in the movie Sound of Music was her real mother and wished Mr. Rogers on TV was her real father. Beccah could never understand her mother and knew even less of her father. A shallow pool of early childhood memories was her only source in which she could find the semblance of a family. In the absence of a normal childhood, she envied her friends who were growing up with a domestic mother and a protective father.

The emotional rift only deepened as the toll of taking care of her mother persisted, and after a certain age, Beccah stopped looking after her mother. She becomes a woman of her own means. Beccah now works as an obituary writer at a local newspaper. Her early ambition to make her mark as a serious journalist digresses into simply turning in copy after copy, and her relationships with her boyfriends prove utterly unsatisfying.

Then suddenly, a turning point in her life arrives with the news of her mother’s death.

20

Even though she struggles for days with the task of writing her mother’s obituary, Beccah is unable to write even a single line. It is at this time that she rummages through her mother’s belongings and finds a cassette tape which eventually leads her to discover her mother’s secret.

In a Japanese war camp in the Pacific Theater, Akiko, at the age of twelve, was forced to undergo a most humiliating and painful experience. Before she assumed the role of Akiko #41, her name was Soon Hyo, and she was the fourth daughter of a destitute cow trader in a forlorn village in Korea. After both parents died, Soon Hyo’s oldest sister sold her to the recruiters in order to finance her own dowry. At the comfort station, Soon

Hyo, too young to be a vessel for sexual slavery or service, was first given the responsibility of cleaning, cooking, washing, and serving as a handmaid to older women.

Following the brutal death of Akiko, a fiercely defiant Korean comfort woman who would not stop yelling out “Induk,” her Korean name, even at the sight of a sword at her throat, Soon Hyo took her place and became a comfort woman. She inherited not only

Induk’s slave name but also her clothes, shoes, comb, and most significantly her unflinching spirit, which explains the source of Akiko’s shaman power.

Not until her mother died, did Beccah have a clue about her mother’s former identity. Akiko hid her past as a comfort woman from her daughter, the only person whom she truly loved and trusted. Her shame forbade her from sharing her emotional wounds and disclosing the ugly world of comfort women. Yet the revelation does not stop there. Despite her seeming incompetence, Akiko was all along a woman of independent means who had her wits about her. She saved her earnings to the last penny and managed to leave a roomy house and a large bank account in Beccah’s name. A Korean mother’s

21

love, as Akiko demonstrates, might speak the language of subdued silence, but it comes in abundance.

A more cathartic moment happens at the end of the novel. Following Akiko’s death, Beccah has dreams in which she finds herself drowning, pulled down by the legs.

The same nightmare haunts her until she has another dream in the last chapter of the novel. But this time Beccah collects courage to meet the force that pulls her down to bottom of the water. When she sees that it is her mother hanging onto her, she yields. She expects to drown, but instead she breathes in air, bright and clear. She soars to the sky like a bird of freedom. When she looks down at the earth, she sees herself “sleeping in bed, coiled tight around a small seed planted” by her mother, “waiting to be born.” As soon as Beccah gives up her struggle with her mother, a symbol of Beccah’s acceptance of her mother, all the loose ends between Beccah and her mother tie together. Here,

Beccah experiences a transformation similar to the one that Akiko experienced after

Induk’s death.

Keller’s keen insight into the mother-daughter relationship and her portrait of crossing cultures can easily be attributed to the fact that she is a biracial Korean who grew up in Hawaii. Vestiges of plurality can be found in the structure of the novel as well.

Alternating the narrative voice between Akiko and Beccah, the novel presents the dark chaos of war as well as the unstable state of Akiko’s conscience which is constantly attacked by intrusive, painful memories. The timeline shifts between past and present keeping the reader on his or her toes. These shifts push the reader to experience the confusing and irrational world of a woman living in her own personal hell created by a tormented past. Keller’s use of the dual narrative voice, her circular writing style, and her

22

literary imagery allows the reader to experience the viewpoints of both mother and daughter. The first person point of view brings the reader close to and elicits empathy for the main characters. The novel falls out of rhythm at times, but it is in this “halt” that the unmitigated rawness of the characters’ emotions is best delivered. Keller’s appeal to the senses of pity, anger, and love draws the reader deeply into the story and even induces a new respect for the people of Korea. Although lacking in superfluous details and slightly tainted by Keller’s misuse of the Korean language, the novel pieces together love, memories, and history to create a unique literary collage of people living under torment few of us can even imagine.

The comfort women who were forced to provide sexual services for Japanese soldiers during World War II has, for long, been an obscure or obtuse topic that many people in America have little knowledge of. This novel sheds light upon many aspects of war crimes committed by the Japanese imperialists which have evaded the attention of the international community. It also opens eyes to what Korean people had to go through during World War II. Readers unfamiliar with shamanism will find Akiko’s ability to communicate with ghosts, to say the least, puzzling. But many readers will also have compassion for Akiko, especially since she was betrayed by the people close to her: her older sister who sold her into the recreation camps; her missionary husband who lusted for her body; and finally her young daughter who thought she was crazy. Keller bares the souls of two distraught individuals. The ultimate symbol of the novel lies in Akiko’s inert yet constant love for Beccah and her determination to weather through humiliation and poverty. Akiko’s perseverance transcends the holocaust of comfort women and her own death. Seen in this way, Comfort Woman is intriguing, humbling, and enlightening. And

23

above of all, it presents us with a valuable learning experience.

The reputation of the novel, however, does not stand without criticism. Voicing their discontent with the novel, a number of Korean-Americans have labeled Comfort

Woman intellectually offensive, because Keller portrays a Korea that is first and foremost palatable to the curiosity of White America. Keller is accused that her depiction of shamanism is less than adequate, which at its best, critics claim, exoticizes Korea. In the postmodern context where ethnic particulars and cultural sensitivity are valued as the primary academic inquiries, Comfort Woman , failing to give a fuller account of Korean culture and religion, ultimately perpetuates the ways in which the West gazes at the East.

In the eyes of foreigners, Korea continues to remain the “other” world full of strange sounds, colors, and people.

Keller has also been criticized for her lack of Koreanness. In addition to the fact that she was raised in a biracial family in Hawaii, her proficiency of the Korean language is questionable for her frequent misuse of Korean words in her novel. Her knowledge of shamanism also appears to be far from sufficient. As Keller is less Korean than Korean

American, that leads us to question, “How important is the author’s ethnic identity in her handling of second-hand memories?”

No critic will seriously dispute the common sentiment that a novelist does not have to possess expert knowledge equaling that of a social scientist or a historian to write a historical or socially conscious novel. At the same time, because this is a novel detailing the tribulations of characters whose ethos is deeply entrenched in a particular historical moment, can a writer like Keller afford to be less than careful? When a novelist manipulates the field of established history and the factual details of a particular

24

country, where do we draw the line in determining her cultural responsibility?

7. A Gesture Life: An Asian Man in Exile, 1999

In the current absence of nationally renowned Asian American male writers, the Korean

American novelist Changrae Lee has been crowned as the prince of an emerging voice.

He has landed comfortable positions as professor of Creative Writing, first at the

University of Oregon, and then Hunter College in New York City and now at Princeton

University. His two novels, Native Speaker (1997) and A Gesture Life (1999) were both published by Riverhead Books owned by Penguin Putnam, which gave him a nice entrée to literary fame and recognition within literary circles. There may be more roads to travel before Lee becomes as well known to lay readers as someone like Amy Tan, and we will have to wait to see if his novels will be read by the academe with the same interest as the novels of Maxine Hong Kingston. Perhaps it is too early to presume that Lee will bend publishing houses to his will and attract academic accolades. Judging from the reception of his books, however, he is well on his way to etching out his own unique version of the

Asian American experience.

Quiet but resilient, reserved but thoughtful, sensitive but armed with survival instincts, Oriental in temperament but a great student of American culture, withstanding the harrowing memories of World War II but fearful of the exuberance of life: these are some of the attributes of Franklin Hata, the protagonist of A Gesture Life . A long-time resident of Bedley Run, an affluent suburb outside Manhattan, Hata, at first glance, seems to be leading a serene and rather effortless life. His business has prospered. His investments keep growing. And his reputation in town has never staggered. He is not only

25

successful but also accepted by his neighbors who do not hesitate to call him “Doc Hata,” even though he is not a doctor, but only the manager of a medical supply store in town.

Hata has earned his honorary title. He looks after people around him, such as Anne

Hickey and her ailing son. He is a surrogate father to the cardiovascular patient Renny

Benarjee and to the super-energetic real-estate broker, Live Crawford, Renny’s on-and-off lover.

Life has taught this gentle-mannered, soft-spoken man a lesson: accept the frailties of life, including death, whether it is your own or another’s. In Hata’s universe, life and death are two sides of the same coin. Life always embraces death. In fact, his spiritual death began a long time ago when he saw a young Korean comfort woman, who touched his soul, brutally slain at the hands of ravaging Japanese soldiers in the Pacific.

The war came to an end more than half a century ago. But the nightmares of the war have never stopped haunting Hata.

During the war, when a fresh load of comfort women was dropped off, Captain

Ono, the surgeon of the platoon, singled out K, the youngest and the prettiest of them, and instructed Hata to excuse her from her sexual service so that he could enjoy her alone.

A black flag was chosen by Ono as their secret sign. Whenever Hata saw a black flag on the front of the infirmary, he was supposed to fetch K and ready her for Ono. In olden times, Japanese villages would raise black flags by their gates to signal the spreading of deadly or contagious disease.

When Hata kills Captain Ono, it seems that K might escape from the cruelty of sexual violation. But the relief K enjoys is all too short-lived. Soldiers in the company knew all along that the captain had given special sanction to K. With the captain’s death,

26

she became fair game for all, no longer to be kept apart for the exclusive pleasure of a high-ranking officer. One day Hata returned from his daily duty of injecting the colonel with sedatives, and found K in the clearing, lying quiet and lifeless.

Hata’s heart is filled with such frightening memories. His tormented soul knows that his days on earth are numbered. Nonetheless, he embraces the treacheries of life as graciously as possible, and that is where the novel hits its highest notes. Hata is not a war hero. He does not possess a flare for romantic chivalry. He is far from being a perfect father either. But there is one attribute of his that cannot be denied: he is a dutiful student of life. Instead of following K into death, Hata stays behind to weather it all.

Since the early days when Lee decided to promote his first book Native Speaker -a novel about a Korean American industrial spy named Henry Park--at conferences and other venues sponsored by Korean Americans, he has been accused of taking advantage of his Korean heritage as a selling point but at the same time denying the Korean community. In addition, his pronounced discomfort with his ethnic identity has unnerved many young Korean Americans who are eager to discover a role model and expect Lee to fill the vacuum. Lee has publicly disquieted the Korean American community on several occasions by declaring that his being labeled a Korean American writer is simply

“uninteresting.”

His aspiration to become an American writer without the hyphen sets Lee in motion to create Franklin Hata. Hata displays the staple characteristics of an aging Asian man--quiet, passive, kind, and gentle. At the same time, the carefully-constructed images which Lee paints on page after page allow the character of Hata to cut through cultural stereotypes. His Asianness does not deter Hata from being fully assimilated into

27

mainstream American culture. As an active element in the melting pot, Hata sees the journey of his life as a man of the world and not of a nation. For Hata, therefore, ethics lie outside the popular political spectrum of minorities and immigrants. The fact that he is of

Korean parentage, that he was raised by a Japanese couple, that he adopted a Korean girl, and finally that his grandson is biracial are not summoned in his inquiries about life’s meaning and purpose. Rather, Hata simply acknowledges that these things make him a man of pride and a loving father.

Lee noted that A Gesture Life was a difficult book to write and that he had to force himself to keep writing. He further professed that he writes precisely because of his discomfort with English. What does he mean by this? At one level, Lee apparently feels enormous passion for the English language. He strives to bring out the beauty and lyricism of the English language, a language which he adopted when he arrived in

America at the age of five. He also aims for perfection of his craft. It would be interesting to know whether Lee is as fastidious as James Joyce who, according to a source, once spent an entire day inserting and deleting a single punctuation mark in his manuscript. With or without the help of a punctuation mark, Joyce created unforgettable images of a modern man who wanders around the streets in Dublin. Hata’s daily walks through the alleys of Bedley Run render a similar image. Only this time it is an Asian man in exile on the East coast of North America.

Lee’s initial project, tentatively titled “Black Flag,” was more directly concerned with Korean comfort women. Prior to undertaking the project, he flew to Korea to interview six former comfort women in Korea. The research he did in Seoul was discarded later along with the manuscript. Then the project veered off to make Hata, a

28

minor character in the original manuscript, the central voice. A Gesture Life , Lee stresses, is a book about a man and the choices he makes.

Lee asserts that he wanted to write a different kind of novel from what is commonly available on the market. This remark counter-measures the current debates which lay a claim to the need to cultivate political sensitivity toward certain ethnic and racial groups. Whether the Korean American community finds Lee’s new novel satisfying or not, A Gesture Life was first and foremost designed to be read as a novel of a subsumed vision. The promise of inclusion indeed becomes the North Star guiding Lee’s creative force. Readers who pick up the book expecting to read of the sufferings of

Korean comfort woman might be disappointed. But if one takes the book as a product of a time when the notion of plurality has come under intellectual and political scrutiny, he or she will encounter in Franklin Hata a character who wears his exile with ease.

8. Silence Broken: The Testimonies of Comfort Women, 1995-

The early publications in English language were at least two collections of testimonials of comfort women as monographs from 1995. True Stories of the Korean Comfort Women edited by Keith Howard, British ethnomusicologist at the University of London, SOAS,

(1995) contained nineteen testimonies from surviving comfort women, which portray the coercion, violence, abduction, rape and false imprisonment they suffered. Numerous

Korean activists on comfort women contributed their efforts and assisted with the collection of the material to make the publication of the book possible to the English language speaking audience. Another was The Comfort Women: Sex Slaves of Japanese

Imperial Forces by an independent researcher and writer George L. Hicks (1995). While

29

they were not serious academic efforts of historical analysis or interpretation but rather a collection of documentary accounts, they nonetheless importantly introduced the critical subject and problem of comfort women in English to the world.

Another book of oral history and testimonials, Silence Broken: Korean Comfort

Women , by Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, an academic-turned-filmmaker, was published in 1999.

This was made into a documentary in 2000, which attempted to offer “flesh and blood” to the narrative as a dramatized account of comfort women. From Dai Sil Kim-Gibson’s homepage (www.twotigers.org), her work is introduced: Silence Broken: Korean Comfort

Women , is a documentary about Korean women forced into sexual servitude by the

Japanese Imperial Military during World War II. After a half-century silence for Korean women, the women finally demand justice for the “crimes against humanity” committed against them. Their compelling testimonies are presented with interviews of Japanese soldiers, recruiters, and scholars. Some of their stories, portrayed in dramatization with their own voices, echo soulful sorrow and the amazing resilience of human spirit. It was broadcast on PBS in the U.S. in May 2000 and broadcast on KBS in Korea in August

2000.

Within the arc of activists and academics who have endeavored for the comfort women controversy and movement, historians, anthropologists, independent scholars and researchers, and government bureaucrats can be included for their efforts to inform, analyze, and address the problem. Among the Japanese scholars, Yoshimi Yoshiaki’s work, (1992) is perhaps best-known as a classic since it confirmed the existence of comfort women by his discovery of Japanese government documents and initiated the debate of comfort women within Japan. There are other scholars and writers such as

30

Hayashi Hirofumi, Yuki Tanaka, Yukiko and Toshiyuki Tanaka, Chizuki Ueno, and Ito

Ruri, among others, who have written on the subject of comfort women over the years, especially on the recent e-journal Japan Focus .

Among Korean-language works, a woman sociologist at Seoul National

University trained at the University of Chicago, Jeong Jinseong’s book, xx, (From the

1990s) is considered a standard classic on the subject. She had long been involved with the comfort women movement from its inception in the early 1990s. Among Korean-

American scholars, Sarah Chunghee Soh, an anthropologist who teaches in San Francisco, has been the most prolific on comfort women. As a conference volume on comfort women, Margaret Stetz and Bonnie Oh’s edited work is also not to be missed. In terms of the collected accounts of the testimonies of Korean comfort women, there are works by

Chungmoo Choi, Kim Hyun Sook, Sangmie Choi Schellstede and Soon Mi Yu and Hye

Seung Chung, in addition to the afore-mentioned books by George Hicks and Keith

Howard. As a Dutch comfort woman, Jan Ruff O’Herne published her own account.

There are other accounts, including those by Filipina and other Asian comfort women.

Among the American and Japanese-American scholars, journalists, and researchers, Alexis Dudden, a historian of modern Japan and Korea, joined the discussion in the late 2000s but has been an active scholar on the issue of comfort women. Several pieces of her e-articles on the comfort women controversy and movement can be found on Japan Focus . A long-time Korea analyst in Washington, D.C., Larry Niksch, the impact and spill-over of his Congressional Research Service report on comfort women is discussed in another chapter of this book by Soon Won Park. There are also Tessa Morris-

Suzuki, Norma Field, and Ken Silverstein, among others, who have written on the

31

relevant subjects surrounding the issue of Japanese colonial legacy and comfort women.

Increasingly, feminist and legal scholars as well as human rights lawyers and activists are becoming more involved in the subject of military sexual slavery and human trafficking which, unfortunately, still continue to occur in the current world.

9. Conclusion

From the 1980s to the present, the cultural, literary and media representations of comfort women evolved and enlarged the discourse and debate of the comfort women controversy and movement. Essentially, the comfort women movement engaged the process of historical redress since the early 1990s for nearly two decades with the government of former colonial power Japan, 1905-1945. The thoughless words and behaviors on comfort women by Japanese politicians in the past fifteen years from 1990 to 2005 demonstrate that the history and legacy problem is far from being resolved. (See

Appendix 1.) Over time, the comfort women movement has also come to address historical justice with the former dictatorial government of Korea, i.e., the Park Chunghee regime, which signed a normalization treaty with Japan in 1965, as much as the patriarchal structure and values of the society.

If the comfort women problematique can be generally described as one of power and powerless, it was more explicitly a phenomenon where all forms of victimization collided in terms of imperialism, colonialism, militarism, and sexism in East Asian history of the twentieth century. It has also been suggested that the comfort women as a historical atrocity was derived, ultimately, from the patriarchical structure and malecentered world and worldview which led to such heinous victimization of women as a

32

government-sanctioned practice. Concerning the culture, context, and critique as well as the course and configuration of the comfort women controversy and movement, perhaps more questions are raised than answered in this essay.

The Comfort Women Controversy

What was the process of evolution or development of scholarship as a discourse and debate?

How has the problem been discussed, or how has the discourse evolved or unfolded over time?

How have the definitions and interpretations evolved of the comfort women over time?

How has the issue been academically framed and interpreted?

What has been the nature and substance of academic scholarship and output in terms of ideas, concepts, and paradigms?

What underscored the process of defining and redefining the problem, including the issues of evidence and interpretation as well as new terminologies and paradigms?

How is it tied to the textbook and other controversies between Korea and Japan in

East Asia?

For example, how was historical consciousness raised through the problem of comfort women as part of the broader complex of legacy of the East Asian holocaust?

What kind of conceptual or paradigmatic shifts can be imagined and explored for

33

the problematique of comfort women?

In what ways the rethinking or reframing of history, gender, femininity and sexuality possible in light the past history of colonial sexual slavery, beyond the oft-cited academic categories of nation, gender, race and class?

The Comfort Women Movement

What has been the source of longevity over the past twenty years?

Who have been the main visionaries, architects, or leaders of the movement?

What are the strategic aims and agendas?

How successful has the movement been in terms of reaching its goals?

How has the movement been financially or organizationally supported and sustained? And how has the substance of the movement transformed or adjusted to the external environment?

What were the lessons learned from the comfort women movement?

What is the nature of new strategic vision and direction?

To consider and define the comfort women controversy and movement as an inquiry or praxis, it appears that new genres, terminologies, and paradigms of conceptualizing may be necessary. To expand the definition, conceptiualization, and paradigmization of the subject of comfort women with comparative and documentary insights from world history, I believe that the following categories will increasingly reframe the comfort women discourse, controversy and movement. In terms of the notion or trope of

“holocaust” beyond the Nazi holocaust, there has been a number of books appearing from

34

over a decade ago in 1998, since Iris Chang and other books have emerged to describe the historical inhumanity committed by Japan as “East Asian holocaust”. For instance, there is Hopes for a Network: The Asian Holocaust 1931-1945 -- Hidden Holocaust in World

War II by the Japanese Army: Unit 731, BCW, Nanjing Massacrea, Comfort Women.

Another way of perceiving and defining the comfort women problem is to recognize and assess it as “mass rape” during wartime and more works are increasingly being done to report and analyze the special vulnerability and victimization of women, whether in

Africa, East Europe, or Burma. More information continues to be unearthed about the historical fact and evidence of mass rape during wartimes. The issue of wartime rape or organized mass rape is increasingly gaining academic and media attention, and the idea of comfort women as mass rape should be further studied as a subject of inquiry. As so many of the comfort women were murdered at the end of Pacific War by Japanese military, it is also possible to view the problem as “genocide”, with growing scholarship on the subject. By an investigative reporter, Samantha Powers’ book on Genocide which occurred during wartime in recent years is helpful in this regard. I have included the concept of “prostitution” here to definitively and explicitly distinguish the comfort women as victims of Japanese military sexual slavery from military or other forms of prostitutes. Expanded numbers of studies are currently being undertaken on the subject of prostitution, legal or illegal as well as historical and anthropological. Further efforts on the subject, whether from the feminist, historical, legal, or activist angles, should add to clarification and definition of the comfort women as not prostitutes, but sex slaves.

While the military sex slaves sanctioned by government would certainly be unique in the annals of human cruelty, broader research on the nature, network and trade of slaves and

35

slavery system in world history can be considered. Valuable comparative insights may be gained for the comfort women inquiry from other practices of historical slavery system, such as the African-American example, among others. Finally, the underlying hope for the inquiry and praxis of comfort women movement rests in the growing network of civil activism and activated and fertilized non-government organizations (NGO’s) of the younger generation in East Asia. And we are indeed beginning to see hopeful signs as we witness expanding historical consciousness and activism of civil organizations within

Korea and Japan as well as other nations.

The Comfort Women as New Paradigmatic Inquiry and Praxis o Holocaust o Mass Rape o Genocide o Prostitution o Slavery

36

APPENDIX I

List of Thoughtless Words on Comfort Women by Japanese Politicians

(Mang’oennok), 1990-2005 (The list needs to be edited.)

1990.6.6

1990.4.21

1994.5.4

Shimizu Tsutao, Job Security Chief, Ministry of Labor

“The task of military comfort women does not have any connection with the [Japanese] government. Private businessmen accompanied the military. No investigation is allowed.”

Ono Masayaki, Councilor, Embassy of Japan

“There was no compulsory hauling of comfort women.

Compensation was finished with the claims negotiation between

Korea and Japan in 1965.”

Nagano Shigeto, Minister of Justice

“Despite the matter of degree, there were comfort women for the

U.S and British troops. Comfort women were licensed prostitution in those days so that it cannot be said as women contempt or discrimination of Korean through the present eyes.”

1994.12.22

1996.5.30

1996.6.4

1996.6.5

1996.7.1

1996.7.18

1996.9.20

1996. 9.23

1997.1.15

Murayama Tomiyichi, Prime Minister

“Personal compensation is impossible. The policy of comfort women did not violate international law. It turned out that there is no reference concerning the matter after the [Japanese] National

Policy Agency’s investigation.”

Atakaki Dadashi, LDP Member

“Comfort women is not a historical fact.”

Atakaki Dadashi, LDP Member

“I cannot believe that the military forced it. There must have been financial payment. Comfort women was a licensed prostitution.”

Okuno Seiske, LDP Member

“Comfort women were part of commercial transaction without compulsion. It is not related to the government.”

Okuno Seiske, LPD Member

“Comfort women was run privately.”

Atakaki Dadashi, LDP Member

“Comfort women were not compulsorily mobilized. There is no evidence of 200,000 victims of Nanjing mass slaughter.”

Sakurauchi Yoshio, Chairman of the Diet, LDP

“Although textbooks mention ‘invasion’ or ‘comfort women’, it was something we could not control, rather than an ‘invasion’. There are many countries which became independent as the result of war.”

Watanuki Damiske, Former Minister of Construction

“There were military nurses, but no comfort women.”

Eto Dakami, Member of the Japanese Diet and LDP

“There is no evidence of compulsory recruitment of military

37

1997.1.24

1997.2.4

1997.2.6

1997.2.27

1998.8.1

2001.2.18

2001.4

2001.4.13

2001.4.13

2004.10.27

2005.3.31 comfort women by Japanese authorities.”

Gajiyama Seyroku, Chief Cabinet Secretary

“Without teaching the prostitution system at the time, mentioning only comfort women issue is ridiculous.” (in criticizing junior high school textbooks)

Nishimura Shingo, Member of the Japanese Diet

“What Eto Dakami and Gajiyama said is all true.”

Shimamura Yoshinobu, LDP Member

“Comfort women must have been proud of themselves serving the

Japanese military. They were gathered by prostitution traders, not by the Japanese military, and most of Korean or Chinese did that job.”

LDP Member and Young Committee on the Japanese Perspective and History Textbooks

“Without any accurate proof of the comfort women, the then chief cabinet secretary Gonoyohei approved the Japanese government’s participation in the problem of comfort women under compulsion in

1993.”

Nakagawa Showichi

“The issue of comfort women cannot be in textbook because compulsory recruitment is not clear.”

Norota Yoshinari

“Only by denying the past, Japan’s education system can be changed. Due to the war initiated by Japan, Asian countries did not become colonies of Western world powers.”

Sakamoto Dakao, Professor, Japan Graduate Institute of Studies

“Describing the ‘Sex’ issue in the special situation such as combat field comfort women system in the junior school textbook is problem. The change of Japanese toilet structure and Japan’s war crime are not supposed to be taken as legitimate Japanese history.”

Hujioka Nobukatsu, Professor, Tokyo University

“It is not true that there was a compulsory recruitment by Japanese military of [comfort women]. It is common to have licensed quarters for soldiers for any country. Japan also has the right to interfere in foreign textbooks.”

Dakubo Dadae, Professor, Kyorin University

“It is not proper to teach about comfort women to junior school students. If we do not put patriotism into Japanese textbooks, the nation will collapse.”

Nakayama Nariaki, Education Minister

“There are many self-torturing descriptions in Japan’s history textbooks. It is good that expressions such as ‘comfort women’ or

‘compulsory recruitment’ have been reduced.”

Shimomura Hakubun, Officer, Ministry of Education

“Considering the growth and development stage of children, it is not proper to put the word ‘comfort women’ in junior high school

38

2005.4.13

2005.6.13 history textbooks. The comfort women really existed, and I do not deny the fact. However, the terms of ‘compulsory recruitment’ or

‘comfort women’ did not exist at the time.”

Hujioka Nobukasu, Professor, Dakushoku University

“I think that the people demonstrating in front of the Japan embassy in Korea are not real military comfort women, but agents from

North Korea.”

Nakayama Nariaki, Education Minister

“The term of military comfort women did not exist at the time

(during the second World War). The problem was to insert the term in textbooks. It is good to get rid of the wrong things from textbooks.”

1. The circumstances of the birth and origins of the Korean Council for comfort women can be found in xx by Margaret Stetz and Bonnie Oh et al., which describes the early creation process of Jeongdaehyop.

39