Realism - Primary Sources v2

advertisement

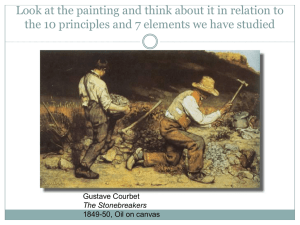

Humanities – Visual Art Realism: Primary Sources (mostly related to Gustave Courbet) The following passages are culled from primary sources. The first two passages are statements by Gustave Courbet, the French painter most strongly associated with a “realist” school or movement. In the third passage, the anarchist philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, an important friend of Courbet’s, asserts some of his views on the place of art in society, with some specific reference to Courbet. The penultimate passage is from one of several responses by the French novelist Emile Zola to the works of Edouard Manet, another important painter sometimes labelled a realist. Finally, the poet Charles Baudelaire, who responded to works by both Courbet and Manet, is represented in the form of a diatribe on the advent of photography. Note: Both Proudhon and Baudelaire are included, among many other contemporaries, in one of Courbet’s major works, The Painter’s Atelier: A Real Allegory Determining Seven Years of My Life as an Artist. In addition, Manet painted more than one image of Zola. The interchange between writers/critics, painters, and social theorists was very lively in this period. Italicized passages are introductory material written by Linda Nochlin to give background for the primary sources. GUSTAVE COURBET: 1819-1877 The Realist Manifesto Gustave Courbet, leader and artistic embodiment of the Realist movement, had attracted scandal and controversy since exhibiting his gigantic Burial at Ornans and Stone-Breakers at the Salon of 1850-1851. Courbet's determination to paint unelevated, familiar subjects (preferably those from around his native village of Ornans in the Franche-Comte) in a broad straightforward manner, on the grand scale hitherto reserved for historical or religious painting, was immediately equated with social anarchy and political revolution by public and critics during the period of conservative reaction following the downfall of the 1848 Revolutionary Government. When Courbet's major works, the Burial at Ornans and the newly painted Artist's Studio, were rejected by the jury of the Universal Exposition of 1855, an infuriated Courbet withdrew the eleven pictures that they had accepted and had his own exhibition building constructed on the Avenue Montaigne, where, with customary bravado, he held a one-man show in competition with the official international exhibition. The so-called "Realist Manifesto," reminiscent of the political manifestoes of this stormy period both in its aggressive tone and in its concise setting-forth of a program, was actually the introduction to the Catalogue of Courbet's private exhibition. According to some authorities, Courbet's ideas were put into coherent form by the realist writer and critic Champfleury (see pp.36 to 45), Courbet's staunchest supporter and initiator of the "bataille réaliste." The title of Realist was thrust upon me just as the title of Romantic was imposed upon the men of 1830. Titles have never given a true idea of things: if it were otherwise, the works would be unnecessary. Without expanding on the greater or lesser accuracy of a name which nobody, I should hope, can really be expected to understand, I will limit myself to a few words of elucidation in order to cut short the misunderstandings. I have studied, outside of any system and without prejudice, the art of the ancients and the art of the moderns. I no more wanted to imitate the one than to copy the other; nor, furthermore, was it my intention to attain the trivial goal of art for art's sake. No! I simply wanted to draw forth from a complete acquaintance with tradition the reasoned and independent consciousness of my own individuality. To know in order to be able to create, that was my idea. To be in a position to translate the customs, the ideas, the appearance of my epoch, according to my own estimation; to be not only a painter, but a man as well; in short, to create living art-this is my goal. Art Cannot Be Taught When in 1861, Courbet received a petition from a group of dissatisfied Ecole des Beaux-Arts students requesting him to open a studio and teach them the theory and practice of Realism, the artist, who had always rejected academic training himself, was at first reluctant. But he then decided to open an unorthodox, democratic atelier, where an atmosphere of mutual aid and equality would reign among the students arid their teacher and where the models were to include not only the usual nudes, but an ox, a horse, and a deer (presumably stuffed) as well. Courbet explained his position in art open letter to his students, dated December 25, 1861, which appeared in the Courrier du dimanche, His ideas about the impossibility of teaching art, his insistence on each individual's personal assimilation of tradition and unique interpretation of his own epoch, and upon the essentially concrete nature of painting itself make this letter Courbet's most important and far reaching contribution to art theory; the artist was probably assisted in putting his thoughts into words by his friend and supporter, the critic Castagnary, who was also in charge of running the studio and who later re-printed the letter under the title "Courbet: His Studio His Theories" in Les Libres Propos, 1864. PARIS, DECEMBER 25, 1861 GENTLEMEN AND COLLEAGUES: You were anxious to open a studio of painting where you would be able to continue your education. as artists without restraint, and you were eager to suggest that it be placed under my direction. Before making any reply, I have to get things straight with you about that word direction. I can't lay myself open to making it a question of teacher and students between us. I must explain to you what I recently had the occasion to tell the congress at Antwerp: I do not have, I cannot have, pupils. I, who believe that every artist should be his own teacher, cannot dream of setting myself up as a professor. I cannot teach my art, nor the art of any school whatever, since I deny that art can be taught, or, in other words, I maintain that art is completely individual, and is, for each artist, nothing but the talent issuing from his own inspiration and his own studies of tradition. I say in addition that, in my opinion, for an artist art or talent can only be a way of applying his own personal abilities to the ideas and objects of the time in which he lives. Above all, the art of painting can only consist of the representation of objects which are visible and tangible for the artist. An epoch can only be reproduced by its own artists, I mean by the artists who lived in it. I hold the artists of one century basically incapable of reproducing the aspect of a past or future century-in other words, of painting the past or the future. It is in this sense that I deny the possibility of historical art applied to the past. Historical art is by nature contemporary. Each epoch must have its artists who express it and reproduce it for the future. An age which has not been capable of expressing itself through its own artists has no right to be represented by subsequent artists. This would be a falsification of history. The history of an era is finished with that era itself and with those of its representatives who have expressed it. It is not the task of modern times to add anything to the expression of former times to ennoble or embellish the past. What has been, has been. The human spirit must always begin work afresh in the present, starting off from acquired results. One must never start out from foregone conclusions proceeding from synthesis to synthesis, from conclusion to conclusion. The real artists are those who pick up their age exactly at the point to which it has been carried by preceding times. To go backward is to do nothing; it is pure loss; it means that one has neither understood nor profited by the lessons of the past. This explains why the archaic schools of all kinds are brought down to the most barren compilations I maintain, in addition, that painting is an essentially concrete art and can only consist of the representation of real and existing things It is a completely physical language, the words of which consist of all visible objects; an object which is abstract, not visible, non-existent, is not within the realm of painting. Imagination in art consists in knowing how to find the most complete expression of an existing thing, but never in inventing or creating that thing itself. The beautiful exists in nature and may be encountered in the midst of reality under the most diverse aspects. As soon as it is found there, it belongs to art, or rather, to the artist who knows how to see it there. As soon as beauty is real and visible, it has its artistic expression from these very qualities. Artifice has no right to amplify this expression; by meddling with it, one only runs the risk of perverting and, consequently, of weakening it. The beauty provided by nature is superior to all the inventions of the artist. Beauty, like truth, is a thing which is relative to the time in which one lives and to the individual capable of understanding it. The expression of the beautiful bears a precise relation to the power of perception acquired by the artist. Here are my basic ideas about art. With such ideas, to think of the possibility of opening a school for the teaching of conventional principles would be going back to the incomplete, received notions which have everywhere directed modern art up to this point. . . . It is not possible to have schools for painting; there are only painters. Schools have no use except for discerning the analytic procedures of art. No school is capable of pressing on to a synthesis in isolation. Painting can not, without falling into abstraction, let a partial aspect of art dominate, whether it be drawing, color, composition, or any other one of the extraordinary multiplicity of means the totality of which alone constitutes this art. I am, therefore, unable to open a school, to form pupils, to teach this or that partial tradition of art. I can only explain to some artists, who would be my collaborators and not my pupils, the method by which, in my opinion, one becomes a painter, by which I myself have tried to become one since my earliest days, leaving to each person the complete control of his individuality, the full liberty of his own expression in the application of this method. To achieve this aim, the organization of a communal studio, recalling those extremely fruitful collaborations of the studios of the Renaissance, could certainly be useful and contribute to the opening of the era of modern painting, and I would eagerly give myself to everything you want of me in order to attain this goal. With deepest sincerity, GUSTAVE COURBET From a letter from Courbet to a friend, the writer Champfleury (who is one of the seated characters on the righthand side of The Painter’s Studio) in explanation of the painting: [The Studio is] perhaps even larger than the Burial, which will show that I am not dead yet, and nor is Realism, since Realism is a fact. It is the moral and physical history of my workshop, first stage; there are those who serve me, who support me in my idea, who participate in my action. There are those who live on life and who live on death. It is society at its top, bottom and middle. In a word, it is my way of seeing society in its interests and its passions. It is the world come to be painted at my place. You see that the picture has no title [ie, there is no story or explicit subject matter]. I shall try to give you a more exact idea of it through a dry description. The scene takes place in my atelier in Paris. The painting is divided into two parts. I am in the middle, painting. To the right are all the shareholders, that is to say friends, fellow workers and amateurs from the art world. To the left is the other world of the trivial life, the people, misery, poverty, wealth, the exploited, the exploiters, people who live on death ... I will list the characters beginning at the extreme left. At the edge is a Jew I saw in England making his way through the febrile activity of the London streets, religiously carrying a money-box on his right arm; while covering it with his left hand he seemed to be saying, 'It is I who am on the right track' ... Behind him is a priest with a triumphant look and a bloated red face. In front of them is a poor withered old man, a republican veteran of '93... , a man of ninety years, holding his ammunition bag, dressed in old white linen made out of patches and a visored cap. He looks down at the romantic cast-offs at his feet. (He is pitied by the Jew.) Next come a hunter; a reaper, a strong-man, a buffoon, a textile peddler, a workman's wife, a worker, an undertaker, a death's head on a newspaper, an Irishwoman suckling a child, an artist's dummy... The cloth peddler presides over all of this: he displays his finery to everyone, and all show the greatest interest, each in his own way Behind him, lying in the foreground, are a guitar and a plumed hat. Second part. Then comes the canvas at my easel with me painting it seen from the Assyrian side of my head. Behind my chair is a nude female model. She is leaning on the back of my chair to watch me paint for a moment. Following this woman come Promayet with his violin ... Then behind him are Bruyas, Cuenot, Buchon, Proudhon (I would like to have the philosopher Proudhon who is of our way of seeing; I would be pleased if he would pose. If you see him, ask if I can count on him). Then it is your turn towards the foreground of the composition. You are seated on a stool, legs crossed and a hat on your lap. Next to you and closer to the foreground is a woman of the world and her husband, both luxuriously dressed. Then towards the extreme right, sitting on the edge of a table, is Baudelaire reading a large book... [But] I have explained it all to you quite badly. I started on the wrong side. I should have begun with Baudelaire, but it would take too long to start again. You'll have to understand it as best you can. The people who want to judge will have their work cut out for them, they will manage as best they can. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon The Aim of Art To paint men in the sincerity of their natures and their habits, in their work, in the accomplishment of their civic and domestic functions, with their present-day appearance, above all without pose; to surprise them, so to speak, in the dishabille of their consciousness, not simply for the pleasure of jeering, but as the aim of general education and by way of aesthetic information: such would seem to me to be the true point of departure for modern art. This does not exclude, in the future, exhibitions more flattering to our vanity, more idealized, since it is thus that the ideal is understood. But-and I don't hide it-I do not expect to see anything of the sort; I do not think that nowadays either Courbet or anyone else will succeed in it. Let us humble ourselves beneath the weight of our unworthiness. It is really not such a trifling thing to be able to show us as we are. In all these respects, I dare say that, aside from the finish of the execution, . . . the painting of Courbet is more serious and higher in its aim than almost anything that the Dutch school has left. . . It is against this degrading theory of art for art's sake that Courbet and, with him, the whole school called realist up until the present, boldly arise and energetically protest. 'No," says he (I translate here Courbet's ideas as embodied in his works, rather than citing them from his speeches): "no, it is not true that the only aim of art is pleasure, for pleasure is not an end; it is not true that it has no other aim but itself, for everything sticks together, everything is connected, everything is conjoined, everything has an aim in humanity and in nature: the idea of a faculty without aim, of a principle without consequence, of a cause without effect is as absurd as that of an effect without a cause. Art has the objective of leading us to the knowledge of ourselves by the revelation of all our thoughts, even the most secret ones, of all our tendencies, of our virtues, of our vices, of our ridiculousness, and in this way it contributes to the development of our dignity, to the perfecting of our being. It was not given to us to feed ourselves with myths, to intoxicate ourselves with illusions, to deceive ourselves and lead ourselves into evil with mirages as the classicists and romantics would have it, as well as all the sectarians of a vain ideal, but rather, to deliver ourselves from these harmful illusions by denouncing them . . .” From Philosophie du progrès, on work [a central concept for Courbet and Realism] What neither gymnastics, politics, music, philosophy, nor all combined have been able to do, Work will accomplish. Just as in ancient times beauty was brought by the gods, in the distant future beauty will be revealed by the worker, by the veritable ascetic; and it is in the innumerable forms of industry that beauty will find diverse forms of expression, each one original and true. Then, finally, . . . laborious mankind, more beautiful and more free than the Greeks had ever been, with no nobles or slaves, with no magistrates or priests, will form all together on the cul-tivated Earth a familv of heroes, sages, and artists. (Note: In art there are really only two periods: the religious or idolatrous epoch, to which Greece gave the highest expression; and the industrial or humanitarian epoch, which has just barely begun. . . . For our swiftest regeneration I would like to burn all the museums, cathedrals, palaces, salons, and boudoirs, including all of their furnishings, both ancient and modern. Then forbid artists to practice their art for fifty years. The past forgotten, we might be able to accomplish something.) A supposed conversation between Courbet and Proudhon about Courbet’s painting The Stonebreakers: "Tell me now, Citizen Master Painter, what brought you to do your Stonebreaker&?" "But," answered the Citizen Master Painter, "I found the motif picturesque and suitable for me." "What? Nothing more? . . . I cannot accept that such a subject be treated without a preconceived idea. Perhaps you thought of the sufferings of the people in representing two members of the great family of manual laborers exercising a profession so difficult and so poorly remunerated?" "You are right, Citizen Philosopher, I must have thought of that." From that time on it was not unusual to hear Courbet say: "One would think I paint for the pleasure of it, and without ever having meditated my subject. . . . Wrong, my friends! There is always in my painting a humanistic philosophical idea more or less hidden. . . . It is up to you to find it." -Account of a conversation between Courbet and Proudhon in the early 1850s, from Alexandre Schanne, Souvenirs de Schaunard, Paris, 1892, p.301. Emile Zola Characteristics of Manet’s Style He is a child of our times. I see him as an analytic painter. All the problems have once more been called into question: science wanted a firm basis and therefore returned to a precise observation of facts. And this movement has been taking place not only in the realm of science; all the disciplines, all human efforts are directed toward the search for sure and definitive principles in nature. Our modern landscapists have gone far beyond our painters of history and genre because they have studied our countryside, content to translate the first spot of forest they come upon. Edouard Manet applies the same method to each of his works. While others rack their brains to invent a new Death of Caesar or a new Socrates Drinking the Hemlock, he calmly places a few objects and people in a corner of his studio and begins to paint the whole thing, carefully analyzing nature all the while. I repeat, he is a simple analyst; his labor is much more interesting than the plagiarisms of his colleagues; art itself thus leads toward certitude. The artist is an interpreter of that which is, and his works have for me the enormous charm of a precise description made in a human and original language. He has been reproached for imitating the Spanish masters. I will agree that there may be some resemblance between his early works and those of these masters; one is always someone's son. But since his Dejeuner sur l'herbe he seems to me to have confirmed clearly that personality which I have tried to explain and briefly comment upon. Perhaps the truth is that the public, seeing him paint Spanish scenes and costumes, decided that he took his models from across the Pyrenees. From this it is not far to go on to an accusation of plagiarism. But it is good to know that if Edouard Manet painted espadas or majos, it was because in his studio he had Spanish costumes which he thought beautiful in color. He visited Spain only in 1866, and his canvases have too individual an accent for anyone to find him nothing but a bastard of Velasquez and Goya . . . Charles Baudelaire [poet and friend of Courbet: he spoke of the “heroism of everyday life.”] The Modern Public and Photography (Salon of 1859) During this lamentable period, a new industry arose which contributed not a little to confirm stupidity in its faith and to ruin whatever might remain of the divine in the French mind. The idolatrous mob demanded an ideal worthy of itself and appropriate to its nature-that is perfectly understood. In matters of painting and sculpture, the present-day Credo of the sophisticated, above all in France (and I do not think that anyone at all would dare to state the contrary), is this: "I believe in Nature, and I believe only in Nature [there are good reasons for that]. I believe that Art is, and cannot be other than, the exact reproduction of Nature [a timid and dissident sect would wish to exclude the more repellent objects of nature, such as skeletons or chamber-pots]. Thus an industry that could give us a result identical to Nature would be the absolute of art." A revengeful God has given ear to the prayers of this multitude. Daguerre was his Messiah. And now the faithful says to himself: "Since Photography gives us every guarantee of exactitude that we could desire [they really believe that, the mad fools!], then Photography and Art are the same thing." From that moment our squalid society rushed, Narcissus to a man, to gaze at its trivial image on a scrap of metal. A madness, an extraordinary fanaticism took possession of all these new sunworshippers. Strange abominations took form. By bringing together a group of male and female clowns, got up like butchers and laundry-maids at a carnival, and by begging these heroes to be so kind as to hold their chance grimaces for the time necessary for the performance, the operator flattered himself that he was reproducing tragic or elegant scenes from ancient history. Some democratic writer ought to have seen here a cheap method of disseminating a loathing for history and for painting among the people, thus committing a double sacrilege and insulting at one and the same time the divine art of painting and the noble art of the actor. As the photographic industry was the refuge of every would-be painter, every painter too ill-endowed or too lazy to complete his studies, this universal infatuation bore not only the mark of a blindness, an imbecility, but had also the air of a vengeance. . . . I am convinced that the ill-applied developments of photography, like all other purely material developments of progress, have contributed much to the impoverishment of the French artistic genius, which is already so scarce. . . . If photography is allowed to supplement art in some of its functions, it will soon have supplanted or corrupted it altogether, thanks to the stupidity of the multitude which is its natural ally. It is time, then, for it to return to its true duty, which is to be the servant of the sciences and arts-but the very humble servant, like printing or shorthand, which have neither created nor supplemented literature. Let it hasten to enrich the tourist's album and restore to his eye the precision which his memory may lack; let it adorn the naturalist's library, and enlarge microscopic animals; let it even provide information to corroborate the astronomer's hypotheses; in short, let it be the secretary and clerk of whoever needs an absolute factual exactitude in his profession-up to that point nothing could be better. But if it be allowed to encroach upon the domain of the impalpable and the imaginary, upon anything whose value depends solely upon the addition of something of a man's soul, then it will be so much the worse for us! It is an incontestable, an irresistible law that the artist should act upon the public, and that the public should react upon the artist; and besides, those terrible witnesses, the facts, are easy to study; the disaster is verifiable. Each day art further diminishes its self-respect by bowing down before external reality; each day the painter becomes more and more given to painting not what he dreams but what he sees. Nevertheless it is a happiness to dream, and it used to be a glory to express what one dreamt. But I ask you! does the painter still know this happiness? . .