Punic War Gale documents

Connolly, Peter.

Hannibal and the enemies of Rome / written

937

C77h and illustrated by Peter Connolly. London : Macdonald

Educational ; 1978.

Details

My Bookbag

921

H19

Lamb, Harold.

Hannibal. Los Angeles : Pinnacle, c1958.

Details

My Bookbag

FIC

HARRIS

1999

Details

Harris, Thomas,

York, N.Y. :

My Bookbag

Hannibal / Thomas Harris. New

Delacorte Press, c1999.

© 2003 Mandarin Library Automation, Inc.

All Rights Reserved.

Punic Wars Begin, 264 B.C.

DISCovering World History. Online ed. Detroit: Gale, 2003.

About this Publication

How to Cite

Source Citation

Spanish

Punic Wars Begin, 264 B.C.

Table of Contents: Further Readings | View Multimedia File(s)

Use of military force

Principal Personages

Hiero, King of Syracuse 265-215 B.C.

Appius Claudius Caudex, consul in 264 B.C. and leader of the prowar faction in Rome, who led the first campaign into Sicily

Marcus Atilus Regulus, consul in 267 and 256 B.C., another leader of the war party who led the Roman invasion of Africa

Hamilcar Barca (270- 229), Carthaginian general in Sicily at the end of the war , and father of Hannibal the

Great

Summary of Event

The first Punic War was a milestone in Roman history. Entry into this conflict committed Rome to a policy of expansion on an altogether new scale; prosecution of the war marked the emergence of Rome as a world power; disposition of conquered territories reshaped its political condition domestically as well as in foreign affairs.

The Mediterranean world in the early third century B.C. consisted in the east of large territorial empires in areas conquered by Alexander the Great. In the west was Carthage, dominating the coasts of Africa and

Spain, while Rome ruled a network of allied cities in central Italy. In the center was Sicily, the only portion of the Greek world where the imperial ideal had failed to replace the older system of numerous independent city-states. Sicily was an anachronism, certain to attract efforts on the part of the Hellenistic monarchies to attach it to one or another of the eastern Empires. Carthage and Rome were equally certain to resist the establishment of Hellenistic powers in the western Mediterranean. When Pyrrhus, King of Epirus, led his armies into Italy and Sicily, he first met the resistance of Rome, then of Carthage. The failure of his Sicilian campaign between 280 and 275 B.C., left a power vacuum little different from that which existed before, and it was only a matter of time before Rome and Carthage could be expected to come into conflict there.

The occasion of Roman involvement in Sicily, and the beginning of the First Punic War , may have seemed of relatively slight importance. The Mamertines, once mercenary soldiers of Syracuse who had seized the city of Messana and used it as a base of operations in northeast Sicily, found themselves threatened by the growing power of Hiero, King of Syracuse. They called on the Carthaginians for aid, but then, fearing

domination by these traditional rivals, requested aid from Rome in order to expel the Carthaginian garrison.

Rome was a land power with no navy. The Roman senate, fearing overseas campaigns against a naval power, refused to accept the Mamertines' overtures. But the Roman people, perhaps foreseeing the prosperity they might gain from involvement in the rich territories of Sicily, perhaps merely failing to foresee the extent of the military operations they were initiating, voted to aid the Mamertines. Appius Claudius

Caudex, a leader in the prowar faction, was elected consul for the year 264 B.C. and led an expedition to

Sicily.

In the first phase of the war , the Roman forces aided Messana, while Carthage supported Syracuse. But this phase, and with it the original pretext for the war , was soon over. Hiero of Syracuse had no interest in matching his power against Rome's, nor in being dominated by his erstwhile allies. In 263 B.C., Hiero made peace with Rome on terms that left him extensive territories as well as his independence. Messana was saved. But Carthage and Rome now were in a struggle that neither cared to give up.

Between 262 and 256, Rome pressed hard, driving the Carthaginians into a limited number of military strongholds, and mounting her first fleet, which met with surprising success against the experienced

Carthaginian navy. In 256, under the consul Marcus Atilius Regulus, Rome transported an army into North

Africa; it had initial successes, but the Carthaginians, directed by the Greek mercenary Xanthippus, succeeded the next year in destroying the forces of Rome.

Back in Sicily, the fortunes of war took many turns. On land, Rome controlled extensive territories but

Carthage held her strongholds. At sea, the Roman navy was often victorious even though the loss of one fleet in battle and of others in storms weakened her position. By 247, both powers were fatigued. Peace negotiations stalled, but military efforts were at a minimum for some years.

In 244, the Roman government, too exhausted to build a new fleet, allowed a number of private individuals to mount one with the understanding that they should be repaid if the war were brought to a successful conclusion. In 242 this fleet arrived in Sicily. When a convoy of transports bringing supplies to Carthage's troops was captured, Carthage came to terms. The Carthaginians agreed to evacuate Sicily and pay an enormous indemnity over a long period of time.

Sicily, or many of the territories in it, became Rome's first province. Her annexation of it as a subject, tributepaying territory marked the start of developments that gained in importance through the remaining history of the Roman Republic. By annexing a Hellenic territory Rome became, in a sense, a Hellenistic state, a fact that had a profound effect upon Roman cultural life as well as upon foreign relations. Rome's development of naval capacity made possible commercial and military involvement with all the Mediterranean world. Its need to govern conquered territory caused it to modify city-state institutions and begin constitutional developments that would in the end undo the republican form of government in Rome.

FURTHER READINGS

Frank, Tenney. "Rome and Carthage: The First Punic War," The Macmillan Company, Cambridge

Ancient History . 7(1928)Ch. 21.

Picard, Gilbert Charles; Collete Picard. The Life and Death of Carthage . Trans. by Dominique

Collon. Sidgwick & Jackson, 1968.

Grant, Michael. The Ancient Mediterranean . Charles Scribner's Sons, 1969.

A general history of the Mediterranean world from prehistoric times through the achievement of

Roman domination

Grimal, Pierre; Hermann Bengtson. Hellenism and the Rise of Rome . Trans. by A. M. Sheridan

Smith, Carla Wartenburg. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1968.

A survey of the Mediterranean world in the third century B.C

Heitland, W. E. The Roman Republic . The University Press, 1923.

A thorough, three-volume study of the political and military history of the Roman Republic

Toynbee, Arnold J. Hannibal's Legacy . The University Press, 1965.

A two-volume account of the struggles between Rome and Carthage, and their effects on Italy and

Rome

Warmington, Brian Herbert. Carthage . Praeger, 1960.

A description and history of Carthage

Scipio Africanus (236 B.C.-c. 184 B.C.). Reinhart Lutz.

DISCovering World History. Online ed. Detroit: Gale, 2003.

About this Publication

How to Cite

Source Citation

Spanish

Scipio Africanus

236 B.C.-c. 184 B.C.

Born: 236 B.C.

in Rome

Died: c. 184 B.C.

in Liternum, Campania, Italy

Nationality: Roman (ancient).

Occupation: General.

Table of Contents: Awards | Biographical Essay | Further Readings

Scipio's military victory over Carthaginian forces in Spain and North Africa, brought about by his genius as strategist and innovator of tactics, ended the Second Punic War and established Roman hegemony in the

Western Mediterranean.

Biographical Essay:

Early Life

Publius Cornelius Scipio, known as Scipio Africanus or Scipio the Elder, was born to one of the most illustrious families of the Roman Republic; his father, who gave the boy his name, and his mother,

Pomponia, were respected citizens of the patrician dynasty of the gens Cornelii. At Scipio's birth, Rome had begun to show its power beyond the boundaries of Italy, and the young nation was starting to strive for hegemony west and east of the known world. Coinciding with expansion outward was Rome's still-stable inner structure; nevertheless, the influence of the Greek culture had begun a softening, or rounding, of the

Roman character.

Scipio's early life clearly reflects this transition. His lifelong sympathy with Greek culture made him somewhat suspect in the eyes of his conservative opponents, who accused him of weakening the Roman spirit. On the other hand, as a patrician youth, he must have received early military training, for Scipio entered history (and legend) at the age of seventeen or eighteen, when he saved his father from an attack by hostile cavalry during a skirmish with the invading forces of Hannibal in Italy in 218.

His military career further advanced when Scipio prevented a mutiny among the few survivors of the disastrous Battle of Cannae in 216. As a military tribune, the equivalent of a modern staff colonel, he

personally intervened with the deserters, placed their ringleaders under arrest, and put the defeated army under the command of the surviving consul.

In 211, another serious defeat for Rome brought Scipio an unprecedented opportunity. In Spain, two armies under the command of his father and an uncle had been defeated, and the commanders were killed.

Although he was still rather young —twenty-seven according to the ancient historian Polybius—and had not served in public office with the exception of the entry-level position of curulic aedile (a chief of domestic police), Scipio ran unopposed in the ensuing election and became proconsul and supreme commander of the reinforcements and the RomanRoman in Spain.

His election attests the extraordinary popularity which he enjoyed with the people of Rome and later with his men. So great was his reputation, which also rested partly on his unbounded self-confidence and (according to Polybius) a streak of rational calculation, that people talked about his enjoying a special contact with the gods. A religious man who belonged to a college of priests of Mars, Scipio may himself have reinforced these adulatory rumors. Whether his charisma and popularity were further aided by particularly "noble" looks, however, is not known. Indeed, all the extant representations of him, no matter how idealized, do not fail to show his large nose and ears, personal features which do not detract from the overall image of dignity but serve to humanize the great general.

His marriage to Aemilia, the daughter of the head of a friendly patrician family, gave Scipio at least two sons and one daughter, who would later be mother to the social reformers Gaius and Tiberius Gracchus.

Life's Work

Arriving in Spain, Scipio followed the strategic plan of continuing the offensive warfare of his father and uncle and thus trying to tear Spain, their European base, away from the Carthaginians. After he had reorganized his army, Scipio struck an unexpected blow by capturing New Carthage, the enemy's foremost port, in 209. A year later he launched an attack on one-third of the Carthaginian forces at Baecula, in south central Spain. While his light troops engaged the enemy, Scipio led the main body of Roman infantry to attack both flanks of the Carthaginians and thus win the battle. Hasdrubal Barca, the Carthaginian leader, however, managed to disengage his troops and escape to Gaul, where Scipio could not follow him, and ultimately arrived in Italy.

The decisive move followed in 206, when Scipio attacked the united armies of Hasdrubal, the son of Gisco, and Mago at Ilipa (near modern Seville). Meanwhile, his generous treatment of the Spanish tribes had given him native support. Scipio placed these still-unreliable allies in the center of his army, to hold the enemy, while Roman infantry and cavalry advanced on both sides, wheeled around, and attacked the Carthaginian war elephants and soldiers in a double enveloping maneuver which wrought total havoc.

Scipio's immediate pursuit of the fleeing enemy succeeded so completely in destroying their forces that

Carthage's hold on Spain came to a de facto end. After a punitive mission against three insurgent Spanish cities, and the relatively bloodless putting down of a mutiny by some Roman troops, Scipio received the surrender of Gades (Cádiz), the last Carthaginian stronghold in Spain.

When Scipio returned to Rome, the senate did not grant him a triumph. He was elected consul for the year

205, but only his threat to proceed alone, with popular support, forced the senate to allow him to take the war to Carthage in North Africa rather than fight an embattled and ill-supported Hannibal in Italy. In his province of Sicily, Scipio began with the training of a core army of volunteers; uncharacteristically for Roman thought, but brilliantly innovative in terms of strategy, he emphasized the formation of a strong cavalry.

In 204, Scipio landed in North Africa near the modern coast of Tunisia with roughly thirty-five thousand men and more than six hundred cavalry. He immediately joined forces with the small but well-trained cavalry detachment of the exiled King Masinissa and drew first blood in a successful encounter with Carthaginian cavalry under General Hanno.

Failing to capture the key port of Utica, Scipio built winter quarters on a peninsula east of the stubborn city.

One night early the next spring, he led his army against the Carthaginian relief forces under Hasdrubal and

King Syphax, who had broken an earlier treaty with Scipio. The raid was successful, and the camps of the

enemy were burned; now Scipio followed the reorganized adversaries and defeated them decisively at the

Great Plains. The fall of Tunis came soon after.

Beaten, Carthage sought an armistice of forty-five days, which was granted by Scipio and broken when

Hannibal arrived in North Africa. Hostilities resumed and culminated in the Battle of Zama. Here, the attack of the Carthaginian war elephants failed, because Scipio had anticipated them and opened his ranks to let the animals uselessly thunder through. Now the two armies engaged in fierce battle, and, after the defeat of the Carthaginian auxiliary troops and mercenaries, Scipio attempted an out-flanking maneuver which failed against the masterful Hannibal. In a pitched battle, the decisive moment came when the Roman cavalry and that of Masinissa broke off their pursuit of the beaten Carthaginian horsemen and fell upon the rear of

Hannibal's army. The enemy was crushed.

After the victory of Zama, Scipio granted Carthage a relatively mild peace and persuaded the Roman senate to ratify the treaty. When he returned to Rome, he was granted a triumph in which to show his rich booty, the prisoners of war (including Syphax), and his victorious troops, whom he treated generously. It was around this time that Scipio obtained his honorific name "Africanus."

There followed a period of rest for Scipio. In 199 he took the position of censor, an office traditionally reserved for elder statesmen, and in 194 he held his second consulship. An embassy to Masinissa brought

Scipio back to Africa in 193, and in 190 he went to Greece as a legate, or general staff officer, to his brother

Lucius. In Greece, the Romans had repulsed the Syrian king Antiochus the Great and prepared the invasion of Asia Minor. Because of an illness, Scipio did not see the Roman victory there.

At home, their political opponents, grouped around archconservative Cato the Censor, attacked Scipio and his brother in a series of unfounded lawsuits, known as "the processes of the Scipios," concerning alleged fiscal mismanagement and corruption in the Eastern war . Embittered, Scipio defended his brother in 187 and himself in 184, after which he left Rome, returning only when the opposition threatened to throw Lucius in jail. Going back to his small farm in Liternum in the Campania, Scipio lived a modest life as a virtual exile until his death in the same year or in 183. His great bitterness is demonstrated by his wish to be buried there instead of in the family tomb near the capital.

Summary

The military victories of Scipio Africanus brought Rome a firm grip on Spain, victory over Carthage, and dominion over the Western Mediterranean. Scipio's success rested on his great qualities as a farsighted strategist and innovative tactician who was bold enough to end the archaic Roman reliance on the brute force of its infantry; he learned the lesson of Hannibal's victory at Cannae. His newly formed cavalry and a highly mobile and more maneuverable infantry secured the success of his sweeps to envelop the enemy.

On the level of statesmanship, Scipio's gift for moderation and his ability to stabilize and pacify Spain secured power for Rome without constant blood-letting. His peace with Carthage would have enabled this city to live peacefully under the shadow of Rome and could have prevented the Third Punic War , had the senate later acted differently.

Finally, Scipio never abused his popularity to make himself autocratic ruler of Rome, although temptations to do so abounded. At the height of his influence in Spain, several tribes offered him the title of king; he firmly refused. After his triumph, the exuberant masses bestowed many titles on the victor of Zama, but he did not grasp for ultimate power. Unlike Julius Caesar, Scipio Africanus served the Roman state; he did not master it. He is perhaps the only military leader of great stature who achieved fame as a true public servant.

Awards:

Areas of Achievement:

Warfare and government

FURTHER READINGS

Dorey, T. A.; D. R. Dudley. Rome Against Carthage . Secker and Warburg, 1971.

Chapters 3 to 7 deal with the Second Punic War and place Scipio's conquests in context. Useful discussion of his campaigns, Roman policy toward Carthage, and the origins of the conflict. Contains many illustrations and maps and an adequate bibliography

Eckstein, Arthur M. Senate and General . University of California Press, 1987.

Generally scrutinizes who had the power to make political decisions. Chapter 8 illuminates various aspects of Scipio's struggle with the senate. Includes a good, up-to-date bibliography

Haywood, Richard M. Studies on Scipio Africanus . Johns Hopkins University Press, 1933. Reprint,

Greenwood Press, 1973.

Revises the account by Polybius, who rejected old superstitions about Scipio but made him more calculating and scheming than Haywood believes is justified. The bibliography is still useful

Liddell-Hart, B. H. A Greater Than Napoleon: Scipio Africanus . Little, Brown and Co., 1927.

Reprint, Biblo and Tannen, 1971.

Popular account of Scipio's life, with emphasis on his military achievements. Scipio is judged sympathetically and praised for tactical innovations and rejection of "honest bludgeon work."

Contains many helpful maps

Scullard, Howard H. Roman Politics 220-150 B.C.

. Clarendon Press, 1973.

Chapters 4 and 5 deal with Scipio's influence on Roman politics and place his career in the context of political and dynastic struggle for control in the Roman Republic. Shows where Scipio came from politically and traces his legacy. Contains appendix with diagrams of the leading Roman families

Scullard, Howard H. Scipio Africanus: Soldier and Politician . Cornell University Press, 1970.

General study and excellent, comprehensive biography. Carefully balanced and well-researched work. Written with a feeling for its subject, which makes it interesting to read. Contains useful maps

Scullard, Howard H. Scipio Africanus in the Second Punic War . Cambridge University Press, 1930.

An in-depth study of Scipio's campaigns and military achievements, highly technical but readable and with good maps. Brings alive Scipio while dealing exhaustively with its subject

Source Citation:

Lutz, Reinhart. "Scipio Africanus (236 B.C.-c. 184 B.C.)." DISCovering World History . Online ed. Detroit:

Gale, 2003. Student Resource Center - Junior . Thomson Gale. Beaver Country Day School. 15 Nov. 2007

<http://find.galegroup.com/srcx/infomark.do?&contentSet=GSRC&type=retrieve&tabID=T001&prodId=SRC-

4&docId=EJ2105100509&source=gale&srcprod=SRCJ&userGroupName=mlin_m_beaver&version=1.0>.

How to Cite

Thomson Gale Document Number:

EJ2105100509

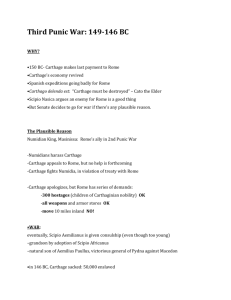

Battle of Zama, 202 B.C.

DISCovering World History. Online ed. Detroit: Gale, 2003.

About this Publication

How to Cite

Source Citation

Spanish

Battle of Zama, 202 B.C.

Table of Contents: Further Readings

Engagement between Roman and Carthaginian armies

Principal Personages

Hannibal (248- 182), Carthaginian general

Hasdrubal Barca (d. 207), younger brother of Hannibal

Publius Cornelius Scipio (236- 184), Roman consul and general

Massinissa (240- 148), King of eastern Numidia, and an ally of Rome

Gaius Laelius, consul 190, and Roman commander under Scipio

Summary of Event

After Hannibal had finally been trapped in southern Italy by the "Fabian tactics" of Rome, the tide of the

Second Punic War turned against him. Scipio's victories in Spain from 208 to 206, and the frustration of the efforts by Hasdrubal, Hannibal 's younger brother, to reinforce Hannibal in 207, prepared the way for an invasion of Africa by Scipio in 204. It was then Rome's turn to ravish the enemy countryside as Hannibal had done for fifteen years in Italy. With a large and well-disciplined army, mostly volunteers, Scipio outwitted two defense forces collected by Carthage, captured the rural areas around the city, and damaged its economy. The Carthaginians offered a truce to gain time in order to effect Hannibal 's return from Italy; he succeeded in getting away with a force of more than ten thousand veterans.

Hannibal spent the winter of 203-202 collecting and training an army for the decisive meeting with Scipio.

Since both Roman and Carthaginian cavalry was limited, the rival generals each sent out appeals for aid to various African chieftains. Scipio turned to an old companion in arms, the wily desert sheik Massinissa, who had fought with the Romans in Spain. In 204-203 Scipio had helped Massinissa defeat a rival for control of a kingdom in Numidia, west of Carthage. But in 202 Massinissa was slower to respond to Scipio than were other African princes who brought cavalry and elephants to aid Hannibal . So Scipio moved his army inland and westward to avoid a major battle until he had secured more cavalry.

Hannibal marched his army in pursuit of the Romans, hoping to force a confrontation before Scipio was ready. When the Carthaginian army came near the village of Zama, about five days' march southwest of

Carthage, he sent scouts to search out Scipio's position. These spies were captured, but after being shown

through the Roman camp they were released. Scipio by this device hoped that their reports would discourage an immediate Carthaginian attack. Polybius, the Greek historian who lived in the first half of the first century B.C., reports that before the battle the two generals actually had a dramatic face-to-face meeting, alone on a plain between two opposing hills where their armies were encamped. However,

Hannibal 's peace proposals were rejected by Scipio, who had recently been encouraged by the arrival of

Massinissa with four thousand cavalrymen and other reinforcements.

On the following day the two armies were drawn up for battle. They were probably about equal in size, although some scholars estimate that Hannibal 's force was as large as fifty thousand men while Scipio's was as small as twenty-three thousand. Certainly the Roman cavalry was stronger. Hannibal placed his eighty elephants in front of his first-line troops, who were experienced mercenaries from Europe and Africa.

Scipio's front line was divided into separate fighting units with gaps between them to allow the elephants to pass through without disarranging the line.

When the battle began, bugles stampeded the elephants, which turned sideways on to Hannibal 's own cavalry stationed on the wings. The Roman cavalry under Laelius and Massinissa took advantage of the confusion to drive the Carthaginian cavalry off the battlefield.

During the infantry battle which ensued, the disciplined front rank of Roman legionaires, closely supported by their second-rank comrades, managed to penetrate Hannibal 's line in places. The second-line troops of

Ca rthage, apparently not as well coördinated, allowed both Punic lines to be driven back with heavy casualties. Hannibal had kept in reserve a strong third line of veterans, intending to attack with this fresh force when the Romans were exhausted, but he allowed a fatal pause during which Scipio regrouped his detachments. The final stage of the battle raged indecisively until the cavalry of Laelius and Massinissa returned to the field to attack the Carthaginians in the rear and destroy most of those encircled by this maneuver. Polybius reports twenty thousand Carthaginian casualties compared to only fifteen hundred

Romans killed.

Hannibal escaped, but Carthage was exhausted and surrendered without a siege, accepting peace terms which took away all Carthaginian possessions outside Africa, imposed a heavy indemnity, and guaranteed the autonomy of Massinissa's kingdom. Scipio returned in triumph to Rome where he was awarded the title

"Africanus." Remarkably undaunted by defeat, Hannibal led Carthage within a few years to economic recovery; later he was forced by Rome into exile, and he fled eastward to aid adversaries of Rome in further wars.

By their victory at Zama, the Romans gained supremacy in the western Mediterranean and launched an imperialistic program which eventually made them dominant throughout most of Europe and the Near East, repressing eastern leadership until the rise of Moslem power.

FURTHER READINGS

Scullard, H. H. Scipio Africanus : Soldier and Politician. Cornell University Press, 1970.

Dodge, T. A. Hannibal . Houghton Mifflin Co, 1891. 2 vols.

Liddell Hart, B. H. A Greater than Napoleon : Scipio Africanus. William Blackwood and Sons, 1926.

A semipopular but solid account lauding Scipio as greater than Caesar, Alexander, and Frederick the

Great

Hallward, B. L. "Scipio and Victory," The University Press, The Cambridge Ancient History .

8(1928)ch. 4.

In discussing the Battle of Zama, this account eulogizes Hannibal as the "consummate strategist" and statesman

Russell, Francis H. "The Battlefield of Zama," Archaeology . 23(April 1970): 120-129. No. 2.

A beautifully illustrated study of the Battle of Zama

Warmington, B. H. Carthage . Robert Hale Ltd, 1960.

A history including a brief description of the Battle of Zama and its consequences for history

Baker, G. P. Hannibal . Dodd, Mead & Company, 1929.

A clear account of Zama with three maps to show different stages of the battle

Cottrell, Leonard. Hannibal, Enemy of Rome . Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1960-1961.

An interesting biography which provides clear battle diagrams

De Beer, Gavin. Hannibal . Viking Press, 1969.

This handsomely illustrated biography gives only a brief account of the Battle of Zama

Source Citation:

"Battle of Zama, 202 B.C." DISCovering World History . Online ed. Detroit: Gale, 2003. Student Resource

Center - Junior . Thomson Gale. Beaver Country Day School. 15 Nov. 2007

<http://find.galegroup.com/srcx/infomark.do?&contentSet=GSRC&type=retrieve&tabID=T001&prodId=SRC-

4&docId=EJ2105240282&source=gale&srcprod=SRCJ&userGroupName=mlin_m_beaver&version=1.0>.

How to Cite

Thomson Gale Document Number:

EJ2105240282

Hannibal Barca (247 B.C.-183 B.C.).

Encyclopedia of World Biography. Ed. Suzanne M. Bourgoin. 2nd ed. Detroit: Gale Research, 1998.

About this Publication

How to Cite

Source Citation

Spanish

Hannibal Barca

247 B.C.-183 B.C.

Born: 247 B.C.

in Africa

Died: 183 B.C.

in Libyssa, Bithynia

Nationality: Carthaginian.

Occupation: military leader.

Table of Contents: Biographical Essay | Further Readings

Biographical Essay:

Hannibal Barca (247-183 BC) was a Carthaginian general and one of the greatest s of the ancient world. A brilliant strategist, he developed tactics of outflanking and surrounding the enemy with the combined forces of infantry and cavalry.

As a boy of 9, Hannibal begged his father, Hamilcar Barca, to take him on the campaign in Spain, but

Hamilcar, before fulfilling this childish wish, made him solemnly swear eternal hatred of Rome. As a young officer in Spain, Hannibal won his first laurels under the command of Hasdrubal, Hamilcar's successor and son-in-law.

Livy gives a remarkable portrait of Hannibal 's physique and character at this time: to the old soldiers he seemed a Hamilcar reborn, as he possessed the lively expression and penetrating eyes of his father; the younger men were won over by his bravery, endurance, simplicity of life, and willingness to share all hardships with his troops. The accusations of cruelty, treachery, and lack of religion must be discounted as anti-Carthaginian war propaganda of Livy's Roman sources.

In Spain

Upon the assassination of Hasdrubal in 221 B.C., Hannibal , at the age of 26, was immediately proclaimed commander in chief by the entire army, an appointment soon afterward ratified by the Carthaginian

Senate.Making New Carthage his headquarters, Hannibal consolidated Carthaginian power in Spain by attacking and defeating the Olcades on the upper Guadiana and the Vaccaei and Carpetani beyond the

Tagus. In the spring of 219 he besieged Saguntum, a city south of the Iberus River (Ebro) and an ally of

Rome. Although he did not formally break the treaty of 226, which had defined the Iberus River as the line of demarcation between the Roman and Carthaginian spheres of influence, the blockade of Saguntum and its final destruction after an 8-month siege brought about the declaration of war.

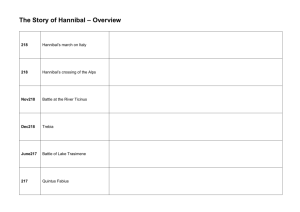

Crossing the Alps

Aware of Roman supremacy on the sea, Hannibal conceived of an invasion of Italy from the north. He wanted to crush the Roman army with his superior land forces in their own territory, especially since he counted on the disaffection of Rome's Italian allies. Thus he crossed the Iberus in the spring of 218, and, after bloody battles with Spanish tribes, he marched with about 40,000 men across the Pyrenees. Once in

Gaul, he hastened to the Rhone River without meeting resistance and, within a week, transported his army and war elephants across the river.

Meanwhile, the Roman consul Publius Cornelius Scipio, who had transported his troops by sea to Massilia

(Marseilles), was moving north on the right bank of the Rhone, but when he heard that Hannibal had already crossed the river, he sent his brother Gnaeus with two legions to Spain, while he himself returned to northern Italy. Hannibal , on the other hand, wanted to cross the Alps and reach the Po Valley before the

Romans were able to collect their forces against an unexpected invader. In 15 days he marched through rugged, unknown mountain passes, with his enormous army of diverse origin and language and his 38 war elephants, in the midst of enemy attacks, landslides, and early autumn snow —a heroic feat which has captured the imagination of historians and poets alike.

When Hannibal finally reached the Po Valley, his army was reduced to half its former size and most of his war elephants were lost. And yet, when he met the army of Publius Scipio at the Ticinus River, Hannibal 's

Numidian cavalry won a decisive victory over the Romans. Scipio, who was seriously wounded, withdrew to the Trebia River south of Placentia, where the consular army of Titus Sèmpronius Longus, recalled by the

Senate from Sicily, joined him. Using the tactics of both ambush and outflanking the enemy, Hannibal defeated the combined armies, causing the loss of about 20,000 Roman soldiers.

In Italy

After spending the winter in the Po Valley, where he gained many recruits among the Gauls and Ligurians,

Hannibal crossed the Apennines in the spring of 217. By ravaging Etruria he provoked the pursuit of the new consul Gaius Flaminius, whom Hannibal trapped with two legions in a defile on the northern shore of

Lake Trasimenus. Rushing down from their ambush on the opposing hills, Hannibal 's troops annihilated almost the entire army and, shortly afterward, intercepted and destroyed the cavalry that was sent to aid

Flaminius.

Now Hannibal marched to Picenum, where he granted his troops a period of rest in the hope that Rome's

Italian allies would defect. He continued to ravage Apulia and Campania without being able to involve the dictator Quintus Fabius, called Cunctator for his tactics of delay, in anything but minor skirmishes. But in the following year, when a new pair of consuls put into effect the aggressive war policy of the Senate, Hannibal beat the Romans in the worst defeat they had ever suffered. This happened at Cannae, where his strategy of outflanking the enemy again brought victory to the Carthaginians over superior numbers.

Now Capua and many other cities in southern Italy revolted against Rome, but Hannibal 's weakened forces prevented him from taking full advantage of his victory. Making Capua his headquarters, he changed from an offensive to a defensive policy, mostly because his home government refused to send him adequate reinforcements. Although he was able to capture Tarentum, conquer Bruttium, and win a few minor victories, he gradually lost ground against the superior numbers of the Romans.

Negotiations with Philip V of Macedon and with Hieronymus of Syracuse proved ineffective, and the small band of Numidian cavalry sent to him from Carthage was insufficient for major warfare. In 211, when he was unable to relieve the Roman siege of Capua, Hannibal marched on Rome, pitched camp on the Anio River at a 3-mile distance from the city, but withdrew again to Apulia in the hope that his brother Hasdrubal would bring fresh troops across the Alps from Spain. This hope was shattered in 207, when his brother's bloody head was thrown at his feet as a testimony to the destruction of Hasdrubal's army in the battle of the

Metaurus. Hannibal now concentrated his forces in Bruttium, where he held his ground for 4 more years, until he was recalled in 203 to defend Carthage against the victorious army of Publius Cornelius Scipio the

Elder (Scipio Africanus Major).

In Africa

Back in his native land after 16 years of victorious warfare in enemy territory, Hannibal was finally defeated by Scipio Africanus in the battle of Zama. Ironically, Hannibal became the victim of his own strategy: Scipio outflanked and surrounded the Carthaginians with the aid of King Masinissa's Numidian cavalry. Hannibal escaped with only a few horsemen and rushed to Carthage, where he counseled peace. The treaty was concluded in 201.

Elected a suffete (civil magistrate) in 197, Hannibal broke the power of the Carthaginian oligarchy and worked for social and economic reforms. His political enemies accused him in Rome of intriguing with King

Antiochus III of Syria. When the Romans sent a commission to investigate the matter, Hannibal fled, first to

Antiochus's court at Ephesus, and, after the latter's defeat at Magnesia in 189, to King Prusias of Bithynia.

Hannibal helped his host successfully in a naval battle against King Eumenes of Pergamum, Rome's ally.

When another senatorial commission was sent to demand from Prusias the surrender of the famous

Carthaginian exile, Hannibal poisoned himself.

FURTHER READINGS

The major ancient sources for the life of Hannibal are Livy, Polybius, and Cornelius Nepos. Among the numerous modern biographies are T. A. Dodge, Hannibal (2 vols., 1891); W. O'C. Morris,

Hannibal (1897); George P. Baker, Hannibal (1929); Harold Lamb, Hannibal : One Man against

Rome (1958); Leonard Cottrell, Hannibal : Enemy of Rome (1960); Robert N. Webb. Hannibal :

Invader from Carthage (1968), especially designed for young people; and Gavin de Beer, Hannibal :

Challenging Rome's Supremacy (1969). On Hannibal 's crossing the Alps see H. Spenser Wilkinson,

Hannibal 's March through the Alps (1911); Cecil Torr, Hannibal Crosses the Alps (1924); and Gavin de Beer, Alps and Elephants: Hannibal 's March (1955). Recommended for general historical background are T. Frank, Roman Imperialism (1914); The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. 8 (1930); and A. J. Toynbee, Hannibal 's Legacy: The Hannibalic War's Effects on Roman Life (2 vols., 1965).

Source Citation:

Heibges, Ursula. "Hannibal Barca (247 B.C.-183 B.C.)." Encyclopedia of World Biography . Ed. Suzanne M.

Bourgoin. 2nd ed. Detroit: Gale Research, 1998. 17 vols.

Student Resource Center - Junior . Thomson Gale.

Beaver Country Day School. 15 Nov. 2007

<http://find.galegroup.com/srcx/infomark.do?&contentSet=GBRC&type=retrieve&tabID=T001&prodId=SRC-

4&docId=EK1631002830&source=gale&srcprod=SRCJ&userGroupName=mlin_m_beaver&version=1.0>.

How to Cite

Thomson Gale Document Number:

EK1631002830

Hannibal Barca (247 B.C.-183 B.C.).

Encyclopedia of World Biography. Ed. Suzanne M. Bourgoin. 2nd ed. Detroit: Gale Research, 1998.

About this Publication

How to Cite

Source Citation

Spanish

Hannibal Barca

247 B.C.-183 B.C.

Born: 247 B.C.

in Africa

Died: 183 B.C.

in Libyssa, Bithynia

Nationality: Carthaginian.

Occupation: military leader.

Table of Contents: Biographical Essay | Further Readings

Biographical Essay:

Hannibal Barca (247-183 BC) was a Carthaginian general and one of the greatest s of the ancient world. A brilliant strategist, he developed tactics of outflanking and surrounding the enemy with the combined forces of infantry and cavalry.

As a boy of 9, Hannibal begged his father, Hamilcar Barca, to take him on the campaign in Spain, but

Hamilcar, before fulfilling this childish wish, made him solemnly swear eternal hatred of Rome. As a young officer in Spain, Hannibal won his first laurels under the command of Hasdrubal, Hamilcar's successor and son-in-law.

Livy gives a remarkable portrait of Hannibal 's physique and character at this time: to the old soldiers he seemed a Hamilcar reborn, as he possessed the lively expression and penetrating eyes of his father; the younger men were won over by his bravery, endurance, simplicity of life, and willingness to share all hardships with his troops. The accusations of cruelty, treachery, and lack of religion must be discounted as anti-Carthaginian war propaganda of Livy's Roman sources.

In Spain

Upon the assassination of Hasdrubal in 221 B.C., Hannibal , at the age of 26, was immediately proclaimed commander in chief by the entire army, an appointment soon afterward ratified by the Carthaginian

Senate.Making New Carthage his headquarters, Hannibal consolidated Carthaginian power in Spain by attacking and defeating the Olcades on the upper Guadiana and the Vaccaei and Carpetani beyond the

Tagus. In the spring of 219 he besieged Saguntum, a city south of the Iberus River (Ebro) and an ally of

Rome. Although he did not formally break the treaty of 226, which had defined the Iberus River as the line of demarcation between the Roman and Carthaginian spheres of influence, the blockade of Saguntum and its final destruction after an 8-month siege brought about the declaration of war.

Crossing the Alps

Aware of Roman supremacy on the sea, Hannibal conceived of an invasion of Italy from the north. He wanted to crush the Roman army with his superior land forces in their own territory, especially since he counted on the disaffection of Rome's Italian allies. Thus he crossed the Iberus in the spring of 218, and, after bloody battles with Spanish tribes, he marched with about 40,000 men across the Pyrenees. Once in

Gaul, he hastened to the Rhone River without meeting resistance and, within a week, transported his army and war elephants across the river.

Meanwhile, the Roman consul Publius Cornelius Scipio, who had transported his troops by sea to Massilia

(Marseilles), was moving north on the right bank of the Rhone, but when he heard that Hannibal had already crossed the river, he sent his brother Gnaeus with two legions to Spain, while he himself returned to northern Italy. Hannibal , on the other hand, wanted to cross the Alps and reach the Po Valley before the

Romans were able to collect their forces against an unexpected invader. In 15 days he marched through rugged, unknown mountain passes, with his enormous army of diverse origin and language and his 38 war elephants, in the midst of enemy attacks, landslides, and early autumn snow —a heroic feat which has captured the imagination of historians and poets alike.

When Hannibal finally reached the Po Valley, his army was reduced to half its former size and most of his war elephants were lost. And yet, when he met the army of Publius Scipio at the Ticinus River, Hannibal 's

Numidian cavalry won a decisive victory over the Romans. Scipio, who was seriously wounded, withdrew to the Trebia River south of Placentia, where the consular army of Titus Sèmpronius Longus, recalled by the

Senate from Sicily, joined him. Using the tactics of both ambush and outflanking the enemy, Hannibal defeated the combined armies, causing the loss of about 20,000 Roman soldiers.

In Italy

After spending the winter in the Po Valley, where he gained many recruits among the Gauls and Ligurians,

Hannibal crossed the Apennines in the spring of 217. By ravaging Etruria he provoked the pursuit of the new consul Gaius Flaminius, whom Hannibal trapped with two legions in a defile on the northern shore of

Lake Trasimenus. Rushing down from their ambush on the opposing hills, Hannibal 's troops annihilated almost the entire army and, shortly afterward, intercepted and destroyed the cavalry that was sent to aid

Flaminius.

Now Hannibal marched to Picenum, where he granted his troops a period of rest in the hope that Rome's

Italian allies would defect. He continued to ravage Apulia and Campania without being able to involve the dictator Quintus Fabius, called Cunctator for his tactics of delay, in anything but minor skirmishes. But in the following year, when a new pair of consuls put into effect the aggressive war policy of the Senate, Hannibal beat the Romans in the worst defeat they had ever suffered. This happened at Cannae, where his strategy of outflanking the enemy again brought victory to the Carthaginians over superior numbers.

Now Capua and many other cities in southern Italy revolted against Rome, but Hannibal 's weakened forces prevented him from taking full advantage of his victory. Making Capua his headquarters, he changed from an offensive to a defensive policy, mostly because his home government refused to send him adequate reinforcements. Although he was able to capture Tarentum, conquer Bruttium, and win a few minor victories, he gradually lost ground against the superior numbers of the Romans.

Negotiations with Philip V of Macedon and with Hieronymus of Syracuse proved ineffective, and the small band of Numidian cavalry sent to him from Carthage was insufficient for major warfare. In 211, when he was unable to relieve the Roman siege of Capua, Hannibal marched on Rome, pitched camp on the Anio River at a 3-mile distance from the city, but withdrew again to Apulia in the hope that his brother Hasdrubal would bring fresh troops across the Alps from Spain. This hope was shattered in 207, when his brother's bloody head was thrown at his feet as a testimony to the destruction of Hasdrubal's army in the battle of the

Metaurus. Hannibal now concentrated his forces in Bruttium, where he held his ground for 4 more years, until he was recalled in 203 to defend Carthage against the victorious army of Publius Cornelius Scipio the

Elder (Scipio Africanus Major).

In Africa

Back in his native land after 16 years of victorious warfare in enemy territory, Hannibal was finally defeated by Scipio Africanus in the battle of Zama. Ironically, Hannibal became the victim of his own strategy: Scipio outflanked and surrounded the Carthaginians with the aid of King Masinissa's Numidian cavalry. Hannibal escaped with only a few horsemen and rushed to Carthage, where he counseled peace. The treaty was concluded in 201.

Elected a suffete (civil magistrate) in 197, Hannibal broke the power of the Carthaginian oligarchy and worked for social and economic reforms. His political enemies accused him in Rome of intriguing with King

Antiochus III of Syria. When the Romans sent a commission to investigate the matter, Hannibal fled, first to

Antiochus's court at Ephesus, and, after the latter's defeat at Magnesia in 189, to King Prusias of Bithynia.

Hannibal helped his host successfully in a naval battle against King Eumenes of Pergamum, Rome's ally.

When another senatorial commission was sent to demand from Prusias the surrender of the famous

Carthaginian exile, Hannibal poisoned himself.

FURTHER READINGS

The major ancient sources for the life of Hannibal are Livy, Polybius, and Cornelius Nepos. Among the numerous modern biographies are T. A. Dodge, Hannibal (2 vols., 1891); W. O'C. Morris,

Hannibal (1897); George P. Baker, Hannibal (1929); Harold Lamb, Hannibal : One Man against

Rome (1958); Leonard Cottrell, Hannibal : Enemy of Rome (1960); Robert N. Webb. Hannibal :

Invader from Carthage (1968), especially designed for young people; and Gavin de Beer, Hannibal :

Challenging Rome's Supremacy (1969). On Hannibal 's crossing the Alps see H. Spenser Wilkinson,

Hannibal 's March through the Alps (1911); Cecil Torr, Hannibal Crosses the Alps (1924); and Gavin de Beer, Alps and Elephants: Hannibal 's March (1955). Recommended for general historical background are T. Frank, Roman Imperialism (1914); The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. 8 (1930); and A. J. Toynbee, Hannibal 's Legacy: The Hannibalic War's Effects on Roman Life (2 vols., 1965).

Source Citation:

Heibges, Ursula. "Hannibal Barca (247 B.C.-183 B.C.)." Encyclopedia of World Biography . Ed. Suzanne M.

Bourgoin. 2nd ed. Detroit: Gale Research, 1998. 17 vols.

Student Resource Center - Junior . Thomson Gale.

Beaver Country Day School. 15 Nov. 2007

<http://find.galegroup.com/srcx/infomark.do?&contentSet=GBRC&type=retrieve&tabID=T001&prodId=SRC-

4&docId=EK1631002830&source=gale&srcprod=SRCJ&userGroupName=mlin_m_beaver&version=1.0>.

How to Cite

Thomson Gale Document Number:

EK1631002830