Ch 8 possibilities, preferences, and choices I. Consumption

advertisement

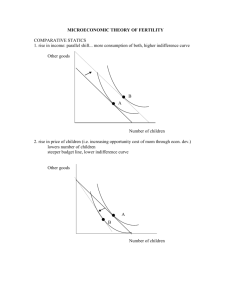

Ch 8 possibilities, preferences, and choices I. Consumption Possibilities A. A household’s consumption choices are constrained by its income and the prices of the goods and services available. The budget line describes the limits to the household’s consumption choices. Figure 8.1 shows a consumer’s budget line. 1. Divisible goods can be bought in any quantity desired (gasoline, for example) 2. Indivisible goods must be bought in whole units (movies, for instance). B. The Budget Equation 1. We can describe the budget line by using a budget equation, which uses the fact that income equals expenditure. a) Calling the price of soda PS, the quantity of soda QS, the price of a movie PM, the quantity of movies QM, and income Y, we can write the budget equation for Lisa who consumes only soda and movies as: PSQS + PMQM = Y, which can be rearranged to: QS = Y/PS – PM/PS QM. 2. A household’s real income is the household’s income expressed as a quantity of goods the household can afford to buy. For example, the vertical intercept for the above budget line, Y/PS, is the consumer’s real income in terms of soda. 3. A relative price is the price of one good divided by the price of another good. The magnitude of the slope of the budget line, PM/PS, is the relative price of a movie in terms of soda. This relative price shows how many sodas must be foregone to see an additional movie. 4. The budget line slope is reflects the rate at which one good can be substituted for another good while keeping the level of income unchanged. The budget line changes if the relative price of a good changes or shifts if the household’s income changes. a) A fall in the price of the good on the horizontal (vertical) axis increases the total affordable quantity of that good and decreases (increases) the slope of the budget line. Figure 8.2a shows the rotations of the budget line after changes in the relative price of movies. b) An increase (decrease) in the household income results in a parallel shift of the budget line rightward (leftward). The slope of the budget line does not change when the consumer’s income changes. The effect of a decrease in income is illustrated in Figure 8.2b. II. Preferences and Indifference Curves A. Figure 8.3 illustrates a consumer’s indifference curve and indifference map, which is based on the idea that people can sort all possible combinations of goods into three groups: preferred, not preferred and indifferent. 1. An indifference curve is a line that shows those combinations of goods among which a consumer is indifferent. a) The consumer prefers points above the indifference curve to points on the indifference curve. And the consumer prefers points on the indifference curve to points below the indifference curve. b) But the consumer is indifferent among (hence its name) all the points on an indifference curve. 2. A single indifference curve is one of a family of curves that form an indifference map, which resemble the contour lines on a topographical map. Figure 8.3b shows three indifference curves from a consumer’s family of indifference curves. B. Marginal Rate of Substitution 1. The marginal rate of substitution, (MRS) measures the rate at which a person will give up good y, (the good measured on the y-axis) to get an additional unit of good x (the good measured on the x-axis) and at the same time remain indifferent (remain on the same indifference curve). 2. The magnitude of the slope of the indifference curve measures the marginal rate of substitution. a) If the indifference curve is relatively steep, the MRS is high. b) If the indifference curve is relatively flat, the MRS is low. 3. The diminishing marginal rate of substitution is the tendency for the marginal rate of substitution of good x for good y to fall as more of good x is consumed. Figure 8.4 shows the diminishing MRS of movies for soda. C. Degree of Substitutability 1. Figure 8.5a shows the indifference curves for ordinary goods, which display diminishing MRS. 2. Figure 8.5b shows the indifference curves for perfect substitutes, which are straight lines with a constant MRS. 3. Figure 8.5c shows the indifference curves for perfect compliments, which are Lshaped. III. Predicting Consumer Behavior A. The consumer’s best affordable point, illustrated in Figure 8.6, meets three conditions: 1. It is on the budget line. 2. It is in the highest attainable indifference curve. 3. It has a marginal rate of substitution between the two goods equal to the relative price of the two goods. B. A Change in Price 1. The price effect shows how a change in the price of a good affects the quantity of that good demanded. 2. As the price of the good on the x-axis decreases (increases), the budget line rotates around the y-axis intercept quantity and becomes flatter (steeper). a) Figure 8.7a shows how a fall in the price of a movie leads the consumer to substitute movies for sodas. The change in the relative prices allows the consumer to reach a higher indifference curve by substituting away from the relatively more expensive good and toward the relatively inexpensive good. b) The new consumption bundle at point J satisfies all three properties of the best affordable point: it is on the new budget line, it is on the highest attainable indifference curve, and the MRS equals the slope of new budget line. 3. Figure 8.7b shows how the consumer’s demand curve can be derived from the budget line and indifference curves. The demand curve is downward sloping, in accord with the law of demand. C. A Change in Income 1. The income effect is the effect of a change in income on the quantity of a good consumed. 2. As the consumer’s income increases, the budget line shifts outward from the origin. The set of affordable combinations of goods increases, which enables the consumer to reach a higher indifference curves. 3. As the consumer’s income decreases, the budget line shifts inward toward the origin. The set of affordable combinations of goods decreases, which enables the consumer to reach only lower indifference curves. Figure 8.8a shows how a decrease in a consumer’s income forces the consumer to a lower indifference curve and decreases the demand for movies. 4. The relative price of the goods has not changed, so the slope of the budget line remains constant. The new consumption bundle satisfies the three properties of the best affordable point: it is on the new budget line, it is on the highest attainable indifference curve, and the MRS equals the slope of the new budget line. 5. When a good is a normal good, the quantity of the good consumed will decrease (increase) as income decreases (increases). Figure 8.8a shows that the quantity of the good consumed has decreased without a change in the relative price of the good, which indicates that the demand curve for that good shifted leftward when income decreased. Figure 8.8b shows how the decrease in the consumer’s income shifts the demand curve for movies leftward. 6. When a good is an inferior good, the quantity of the good consumed will increase (decrease) as income decreases (increases). Because the quantity of the good consumed increases when income falls without a change in the relative price of the good, the demand curve for the good shifts rightward as income decreases. D. Substitution Effect and Income Effect 1. For a normal good, a fall in the price of the good always increases the quantity consumed. We can prove this proposition by breaking the price effect in two different parts: a) The substitution effect is the effect of a change in price on the quantity bought when the consumer (hypothetically) remains indifferent between the original situation and the new situation. To analyze this effect, the consumer moves along the same indifference curve until the MRS equals the slope of the new budget line reflecting the change in price. In Figure 8.9b, the substitution effect is the movement from point C to point K. This effect always leads to an increase in the quantity of the good whose relative price has fallen. b) The income effect is the effect of a change in income at the new relative price. This effect shifts the budget line outward (with no change in its slope) from the consumption reached by the substitution effect to the highest affordable indifference curve attainable on the new budget line reflecting the price change. In Figure 8.9b, the income effect is the movement from point K to point J. For a normal good, the quantity of the good consumed increases when income increases. 2. Because both the substitution effect and income effect lead to an increase in the quantity of the good consumed, a fall in price always increases the quantity consumed for a normal good. As a result, the demand curve for a normal good is always downward sloping. 3. For an inferior good, a fall (rise) in price might not always increase (decrease) the quantity consumed. a) In this case the income effect is negative and counteracts the substitution effect. b) If the negative income effect is stronger than the substitution effect, then a lower (higher) price for an inferior good does not lead to an increase (decrease) in the quantity of that good demanded. c) The demand curve in this case will have a positive slope. But such a case has not been found in any market for real world goods or services. IV. Work-Leisure Choices A. Labor Supply 1. Indifference curves can be used to study the allocation of time between work and leisure. 2. The two goods are leisure and income. “Income” represents all other goods. B. The Labor Supply Curve 1. By changing the wage rate, we can find a person’s labor supply curve. 2. A higher wage rate makes leisure relatively more expensive because the opportunity cost of not working increases. As a result, a higher wage rate creates a substitution effect away from leisure and toward more work. 3. A higher wage rate also has a positive income effect. Leisure is a normal good, so the income effect leads to increased consumption of leisure, which means less work. a) If the income effect is weaker than the substitution effect, the quantity of work hours increases when the wage rate rises. b) If the income effect is stronger than the substitution effect, then the quantity of work hours could decrease when the wage rate rises.