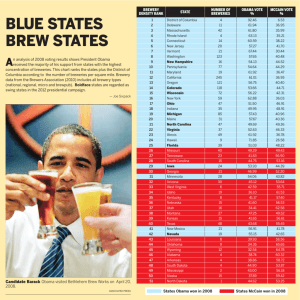

Slate

advertisement