TEDESCHI ED IMPERO OTTOMANO

Otto Liman von Sanders

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

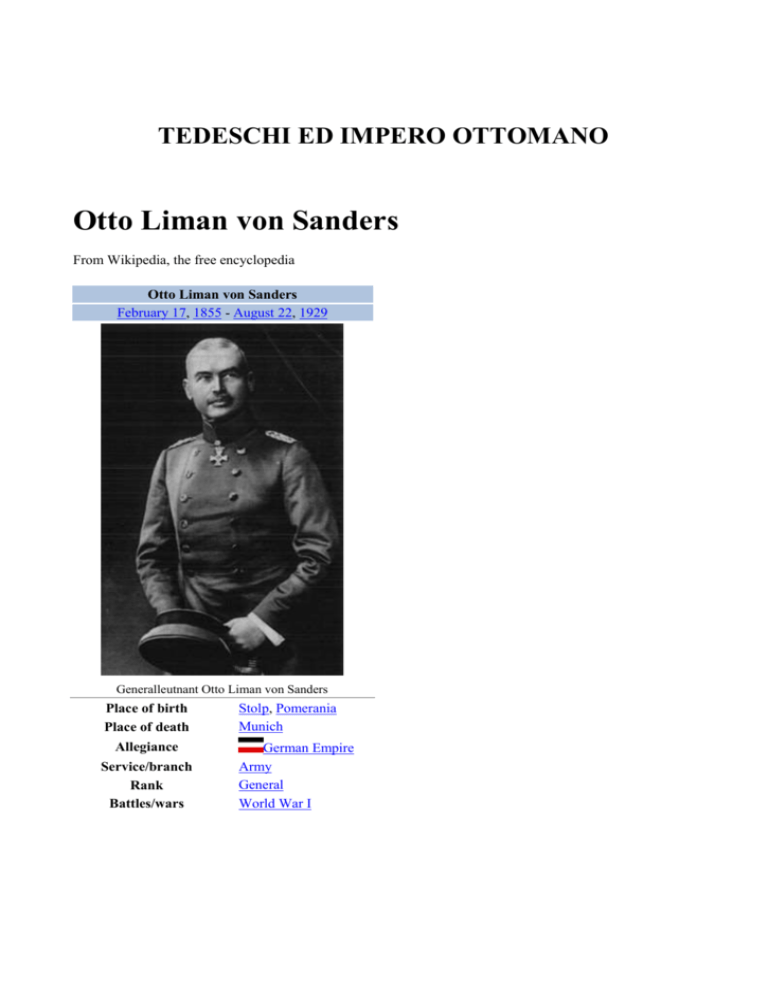

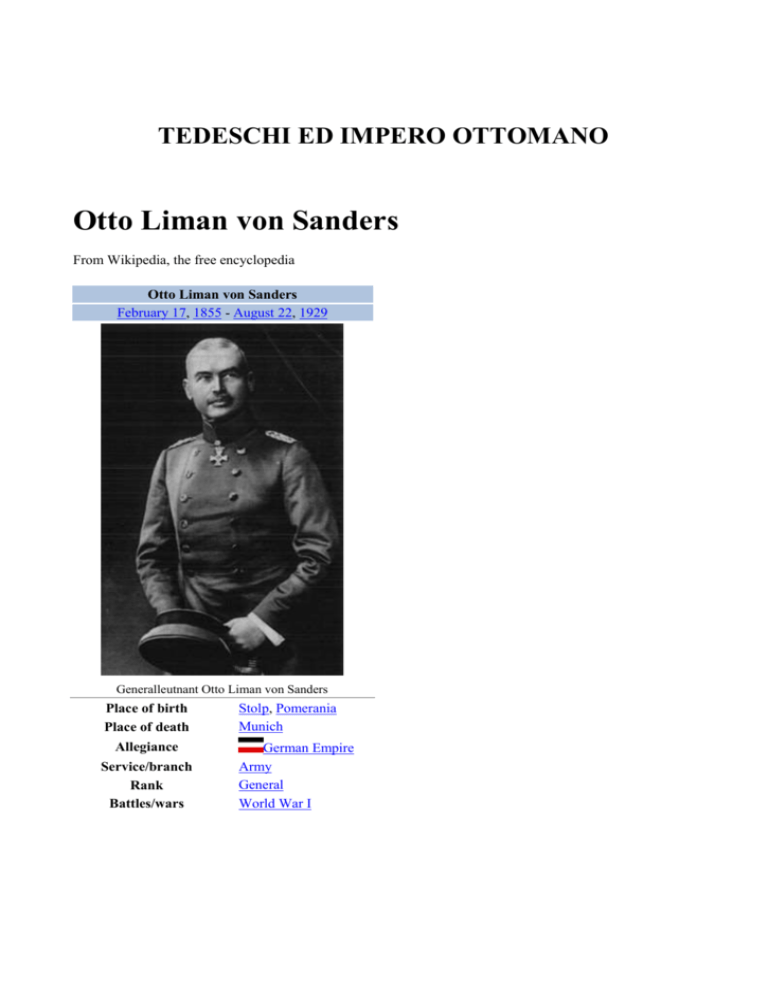

Otto Liman von Sanders

February 17, 1855 - August 22, 1929

Generalleutnant Otto Liman von Sanders

Place of birth

Place of death

Allegiance

Service/branch

Rank

Battles/wars

Stolp, Pomerania

Munich

German Empire

Army

General

World War I

Otto Liman von Sanders, Hans-Joachim Buddecke, and Oswald Boelcke in Turkey, 1916

Generalleutnant Otto Liman von Sanders (February 17, 1855 - August 22, 1929) was a German

general who served as adviser and military commander for the Ottoman Empire during World War

I.

He was born in Stolp in Pomerania. His father was a Prussian nobleman.[1] Like many other

Prussians from aristocratic families, he joined the military and rose through the ranks to Lieutenant

General. Like several Prussian generals before him (e.g., Von Moltke and Baron von der Goltz), he

was appointed the head of a German military mission to the Ottoman Empire in 1913. For nearly

eighty years, the Ottoman Empire had been trying to modernize their army along European lines.

Liman von Sanders would be the last German to attempt this task.

Initially Liman formed a very low opinion of the Ottoman army and its political leadership. In July

1914 (with the war about to start), Enver Pasha offered an alliance, of a sort, with Germany. The

German ambassador in Istanbul, Hans von Wangenheim, after consulting with Liman von Sanders,

refused Enver's offer. The analysis was that the Ottoman army was weak, the government had little

money to spend, and the leadership was incompetent. However, on 1 August 1914 the Germans and

the Ottoman government did sign a secret treaty of alliance; included in the provisions of the treaty

was that the German military mission would wield "effective influence" over the military operations

of the Ottoman armies. [2] At first, this influence was nearly zero. But when Enver Pasha and

Djemal Pasha both suffered defeats, the German military mission took increasing control over the

Ottoman armies.

When the Ottoman forces finally entered the war (after trying to avoid open conflict with the

Alliance for two months), Enver Pasha showed Liman his grand scheme to destroy the Russian

army defending Kars. Liman tried to dissuade Enver from implementing the plan, but his advice

was ignored and Enver Pasha personally led the Ottoman army into its worst defeat of World War I

at the Battle of Sarikamis. Cemal Pasha was given the task of attacking the Suez Canal; his personal

military advisor was the German Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein. The attack on the Suez

also failed, although without enormous losses.

A shaken Enver Pasha returned to Istanbul and took command of the Ottoman army in the area

around the capital. However immediately after a huge British and French fleet destroyed the

Ottoman forts along the Dardanelles (18 March 1915), Enver turned over command to Liman von

Sanders. Defending the Ottoman government was now in the hands of the German general.

Main article: Naval operations in the Dardanelles Campaign

Main article: Battle of Gallipoli

Liman had little time to organize the defences, but he had two things in his favor. First, the Ottoman

5th Army was the best army they had, some 84,000 well-equipped soldiers in six divisions. Second,

he was helped by poor Allied leadership. Instead of using their massive fleet to force a passage

through the straits to Istanbul, the British and French admirals called for ground troops to capture

the Dardanelles peninsula so their battleships could sail on into the Sea of Marmara unmolested.

Liman had just over a month to prepare. Then, on 23 April 1915, the British landed a major force at

Cape Helles. One of Liman's best decisions during this time was to promote Mustafa Kemal (later

known as Atatürk) to commander of the 19th division. Kemal's division literally saved the day for

the Ottomans. His troops marched up on the day of the invasion and occupied the ridge line above

the ANZAC landing site, just as the ANZAC troops were moving up the slope themselves. Kemal

recognized the danger and personally made sure his troops held the ridge line. They were never

forced off despite constant attacks for the next five months.

From April to November 1915 (when the decision to evacuate was made), Liman had to fight off

numerous attacks against his defensive positions. The British tried another landing at Suvla Bay,

but this also was halted by the Ottoman defenders. The only bright spot for the British in this entire

operation was that they managed to evacuate their positions without much loss. However, this battle

was a major victory for the Ottoman army and some of the credit is given to the generalship of

Liman von Sanders.

Early in 1915, the previous head of the German military mission to the Ottoman Empire, Baron von

der Goltz arrived in Istanbul as military advisor to the (essentially powerless) Sultan, Mehmed V.

The old Baron did not get along with Liman von Sanders and did not like the three Pashas (Enver

Pasha, Cemal Pasha and Talat) who ran the Ottoman Empire during the war. The Baron proposed

some major offensives against the British, but these proposals came to nothing in the face of Allied

offensives against the Ottomans on three fronts (the Dardanelles, the Caucusus Front, and the newly

opened Mesopotamian Front). Liman was rid of the old Baron when Enver Pasha sent him to fight

the British in Mesopotamia in October 1915. (Goltz died there six months later just before the

British army at Kut surrendered).

In 1918, the last year of the war, Liman von Sanders took over command of the Ottoman army in

Palestine, replacing the German General Erich von Falkenhayn who had been defeated by British

General Allenby at the end of 1917.

Main article: Sinai and Palestine Campaign

Liman was hampered by the significant decline in power of the Ottoman army. His forces were

unable to do anything more than occupy defensive positions and wait for the British attack. The

attack was a long time in coming, but when General Allenby finally unleashed his army, the entire

Ottoman army was destroyed in a week of fighting (see the Battle of Megiddo). In the rout, Liman

was nearly captured by British soldiers.

After the war ended he was arrested in Malta in February 1919 on charges of having committed war

crimes, but he was released six months later. He retired from the German army that year.

In 1927 he published a book he had written in captivity in Malta about his experiences before and

during the war (there is an English translation[3]). Two years later Otto Liman von Sanders died in

Munich at the age of seventy-four.

References

1. ^ Bernt Engelmann,"Germany without Jews". Translated from German by D.J. Beer, New York:

Bantam Books, 1984, p. 132

2. ^ A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern

Middle East David Fromkin. Owl Books. 636 pages. 2001. ISBN 0-8050-6884-8

^ Five years in Turkey Otto Viktor Karl Liman von Sanders. 326 pages. United States Naval

Gallipoli Campaign

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Battle of Gallipoli)

Campaign

Part of the Middle Eastern Theatre (First World

War)

Gallipoli Campaign, April 1915.

Date

Location

Result

25 April 1915 – 6 January 1916

Gallipoli peninsula, Turkey

Decisive Ottoman victory

Belligerents

British Empire

Australia

British India

Newfoundland

New Zealand

United

Kingdom

Ottoman Empire

Germany[2]

Austria-Hungary[3]

[nb 1]

France

French West

Africa

Commanders

Otto Liman von

Sanders

Mustafa Kemal

Esat Paşa

Strength

5 divisions (initial)

6 divisions (initial)

16 divisions (final)[citation 15 divisions (final)[citation

Sir Ian Hamilton

Lord Kitchener

John de Robeck

needed]

needed]

Casualties and losses

220,000, 59% casualty

300,000 60% Casualty

rate[4]

rate[5]

[show]

v•d•e

Gallipoli Campaign

[show]

v•d•e

Theatres of World War I

The Gallipoli Campaign took place at Gallipoli peninsula in Turkey from 25 April 1915 to 9

January 1916, during the First World War. A joint British Empire and French operation was

mounted to capture the Ottoman capital of Istanbul, and secure a sea route to Russia. The attempt

failed, with heavy casualties on both sides.

In Turkey, the campaign is known as the Çanakkale Savaşları, after the province of Çanakkale. In

the United Kingdom, it is called the Dardanelles Campaign or Gallipoli. In France it is called Les

Dardanelles. In Australia,[6] New Zealand[7] and Newfoundland,[8] it is known as the Gallipoli

Campaign or simply as Gallipoli. It is also known as the Battle of Gallipoli.

The Gallipoli campaign resonated profoundly among all nations involved. In Turkey, the battle is

perceived as a defining moment in the history of the Turkish people—a final surge in the defence of

the motherland as the centuries-old Ottoman Empire was crumbling. The struggle laid the grounds

for the Turkish War of Independence and the foundation of the Turkish Republic eight years later

under Atatürk, himself a commander at Gallipoli.

In Australia and New Zealand, the campaign was the first major battle undertaken by a joint

military formation, the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), and is often considered

to mark the birth of national consciousness in both of these countries. Anzac Day (25 April)

remains the most significant commemoration of military casualties and veterans in Australia and

New Zealand, surpassing Armistice Day/Remembrance Day.

Contents

[hide]

1 Prelude

2 Naval attacks

3 Invasion

o 3.1 Ottoman preparations

o

3.2 Landings

4 The early battles

5 August offensive

6 Evacuation

7 Aftermath

8 Political repercussions

9 Conditions

10 Casualties

11 Popular influence

12 See also

13 Notes

14 References

15 Further reading

16 External links

Prelude

The Allies were keen to open an effective supply route to Russia: efforts on the Eastern Front

relieved pressure on the Western Front. Germany and Austria-Hungary blocked Russia's land trade

routes to Europe, while no easy sea route existed. The White Sea in the north and the Sea of

Okhotsk in the Far East were distant from the Eastern Front and often icebound. The Baltic Sea was

blocked by Germany's formidable Kaiserliche Marine. The Black Sea's only entrance was through

the Bosporus, which was controlled by the Ottoman Empire. When the Ottoman Empire joined the

Central Powers in October 1914, Russia could no longer be supplied from the Mediterranean Sea.

By late 1914, the Western Front, in France and Belgium, had effectively become a stalemate. A new

front was desperately needed. Also, the Allies hoped that an attack on the Ottomans would draw

Bulgaria and Greece into the war on the Allied side. However, an early proposal to use Greek

troops to invade the Gallipoli peninsula was vetoed by Russia as its South Slavic allies would feel

threatened by an expansion of Greek power and influence.

A first proposal to attack Turkey had already been suggested by French Minister of Justice Aristide

Briand in November 1914, but it was not supported. A suggestion by British Naval Intelligence

(Room 39) to bribe the Turks over to the Allied side was not taken up.

Later in November 1914, First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill put forward his first plans

for a naval attack on the Dardanelles, based at least in part on what turned out to be erroneous

reports regarding Turkish troop strength, as prepared by Lieut. T. E. Lawrence. He reasoned that the

Royal Navy had a large number of obsolete battleships which could not be used against the German

High Seas Fleet in the North Sea, but which might well be made useful in another theatre. Initially,

the attack was to be made by the Royal Navy alone, with only token forces from the army being

required for routine occupation tasks.

Panoramic view of the Dardanelles fleet

Naval attacks

Main article: Naval operations in the Dardanelles Campaign

Turkish battery at Gallipoli

On 19 February, the first attack on the Dardanelles began when a strong Anglo-French task force,

including the British battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth, bombarded Turkish artillery along the coast.

Many believed victory to be inevitable. Admiral Carden sent a cable to Churchill on 4 March,

stating that the fleet could expect to arrive in Istanbul within fourteen days.[9] A sense of impending

victory was heightened by the interception of a German wireless message which revealed the

Ottoman Dardanelle forts were close to running out of ammunition.[9] When the message was

relayed to Carden, it was agreed a main attack would be launched on or around 17 March. It

transpired that Carden, suffering from stress, was placed on the sick list by the medical officer,

meaning the fleet was now placed in command of Admiral de Robeck.

On 18 March the main attack was launched. The fleet, comprising 18 battleships as well as an array

of cruisers and destroyers, sought to target the narrowest point of the Dardanelles where the straits

are just a mile wide. Despite some damage sustained by ships engaging the Ottoman forts,

minesweepers were ordered to proceed along the straits. According to an account by the Turkish

General Staff, by 2pm "All telephone wires were cut, all communications with the forts were

interrupted, some of the guns had been knocked out... in consequence the artillery fire of the

defense had slackened considerably"[10]. The French ship Bouvet was sunk by a mine, causing it to

capsize with its entire crew aboard. Minesweepers, manned by civilians and under constant fire of

Ottoman shells, retreated leaving the minefields largely intact. HMS Irresistible and HMS Inflexible

both sustained critical damage from mines, although there was confusion during the battle whether

torpedoes were to blame. HMS Ocean, sent to rescue the Irresistible, was itself struck by an

explosion and both ships eventually sank.[11] The French battleships Suffren and Gaulois were also

badly damaged. All the ships had sailed through a new line of mines placed secretly by the

defenders 10 days before.

The losses prompted the Allies to cease any further attempts to force the straits by naval power

alone. Losses had been anticipated during the planning of the campaign, so mainly obsolete

battleships had been sent which were unfit to face the German fleet, but many naval officers

including de Robeck and Fisher did not consider the losses acceptable. The defeat of the British

fleet had also given the Turks a morale boost, although their gunners had almost run out of

ammunition before the British fleet retreated. The reasons for the decision to turn back are

unclear— if the British had pushed forward with the naval attack, as Churchill demanded, then

Gallipoli might not have been a defeat. On the other hand, it is possible that they would simply have

trapped themselves in the Sea of Marmara, with insufficient force to take Istanbul and a minefield

between themselves and the Mediterranean Sea.

Invasion

After the failure of the naval attacks, it was decided that ground forces were necessary to eliminate

the Turkish mobile artillery. This would allow minesweepers to clear the waters for the larger

vessels. The British Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, appointed General Sir Ian Hamilton

to command the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force that was to carry out the mission.

In early 1915, Australian and New Zealand volunteer soldiers were encamped in Egypt, undergoing

training prior to being sent to France. The infantry were formed into the Australian and New

Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), which comprised the Australian 1st Division and the New Zealand

and Australian Division. General Hamilton also had the regular British 29th Division, the Royal

Naval Division (RND) (Royal Marines and hastily drafted naval recruits) and the French Oriental

Expeditionary Corps (including four Senegalese battalions) under his command.

Ottoman preparations

Disposition of Turkish 5th Army

Heavy artillery from the German armoured cruiser Roon, 1915

There was a delay of over six weeks before many of the troops arrived from Britain, allowing

Turkish forces time to prepare for a land assault. Ottoman commanders began to debate the best

means of defending the peninsula. All agreed that the most effective form of defence was to hold

the highground on the ridges of the peninsula, there was disagreement however as to where they

believed the enemy would land, and hence where to concentrate their own forces. Mustafa Kemal, a

34 year old Lt.-Col., familiar with the Gallipoli peninsula from his operations against Bulgaria in

the Balkan War,[12] believed Cape Helles, the southern tip of the peninsula, and Gaba Tepe would

be the two most likely areas for landing. In the case of the former, Kemal perceived the British

would use their navy to command the land from every side which the tip of the peninsula would

allow. In Gaba Tepe, the short distance to the eastern coast meant forces could easily reach the

Narrows.

Ultimately, Otto Liman von Sanders disagreed. In his view, the greatest danger posed was in Besika

Bay on the Asiatic coast, where Sanders believed British forces would benefit from more accessible

terrain and target the most important Ottoman batteries guarding the straits.[13] As such, Sanders

placed two divisions, a third of the total force of the fifth army, in this area.[13] Two more divisions

were concentrated at Bulair at the northern isthmus of the peninsula, where he believed that should

the area be captured, vital supply and communications lines would be cut.[14] Finally, at Cape

Helles, on the tip of the peninsula, and along the Aegean coast, two more divisions were placed in

the form of the Ninth and Nineteenth division, the latter of which was placed under the command of

Mustafa Kemal. For von Sanders, the bulk of the forces were to be held inland with minor coastal

defences spread across the peninsula. The strategy drew complaints from Turkish commanders,

including Mustafa Kemal, who believed Turkish forces were too widely dispersed and not in a

position to drive the attackers immediately into the sea as soon as their invasion commenced.[15]

The delay in landings by the British allowed Turkish officers to prepare defenses. Von Sanders

notes "The British allowed us four good weeks of respite for all this work before their great

disembarkation...This respite just sufficed for the most indispensable measures to be taken."[16]

Roads were constructed, small boats assembled to carry troops and equipment across the narrows,

beaches were wired and makeshift mines constructed from torpedo-heads. Trenches and gun

emplacements were dug along the beaches whilst troops were regularly taken on long marches to

avoid lethargy.[16] Mustafa Kemal, whose Nineteenth division would become pivotal in the battle,

observed the beaches and awaited signs of an invasion from his post at Boghali, near Maidos.

Landings

Main articles: Landing at Anzac Cove – Landing at Cape Helles

The invasion plan of 25 April 1915 was for the 29th Division to land at Helles on the tip of the

peninsula and then advance upon the forts at Kilitbahir. The Anzacs were to land north of Gaba

Tepe on the Aegean coast from where they could advance across the peninsula and prevent retreat

from or reinforcement of Kilitbahir. The small cove around and in which they landed became

known as Anzac Cove. This sector of the Gallipoli Peninsula became known as 'Anzac'; the area

held by the British and French became known as the 'Helles sector' or simply 'Helles'. The French

made a diversionary landing at Kum Kale on the Asian shore before re-embarking to hold the

eastern area of the Helles sector. There was also a diversion by the Royal Naval Division, including

a one-man diversion by Bernard Freyberg, a three-star General in WW2, at Bulair.

Cape Helles landing beaches.

The Helles landing was made by the 29th Division under the command of Major-General Aylmer

Hunter-Weston, on five beaches in an arc about the tip of the peninsula, designated from east to

west as S, V, W, X and Y beach. The Jewish Legion also landed at Helles on the 25th, as well as a

regiment of British Gurkhas, specifically the 6th Gurkha Rifles, the latter of which took and secured

Sari Bair above the landing beaches.[17]

The commander of the Y Beach landing was able to walk unopposed to within 500 metres of

Krithia village, which was deserted. The British never got so close again. Y Beach was eventually

evacuated the following day as Turkish reinforcements arrived.

The main landings were made at V Beach, beneath the old Seddülbahir fortress, and at W Beach, a

short distance to the west on the other side of the Helles headland.

At V Beach the covering force from the Royal Munster Fusiliers and Royal Hampshires was landed

from a converted collier, SS River Clyde, which was run aground beneath the fortress so that the

troops could disembark directly via ramps to the shore. The Royal Dublin Fusiliers would land at V

Beach from open boats. At W Beach the Lancashire Fusiliers also landed in open boats on a small

beach overlooked by dunes and obstructed with barbed wire. On both beaches the Turkish

defenders were in a position to inflict appalling casualties on the landing infantry. The troops

emerging one by one from the sally ports on the River Clyde presented perfect targets to the

machine guns in the Seddülbahir fort. Out of the first 200 soldiers to disembark, only 21 men made

it onto the beach.[18]

As at Anzac, the Turkish defenders were too few to force the British off the beach. At W Beach,

thereafter known as Lancashire Landing, the Lancashires were able to overwhelm the defences

despite their dreadful losses, 600 killed or wounded out of a total strength of 1,000. The battalions

that landed at V Beach suffered about 70% casualties. Six awards of the Victoria Cross were made

amongst the Lancashires at W Beach. Six Victoria Crosses were also awarded amongst the infantry

and sailors at the V Beach landing and a further three were awarded the following day as they

finally fought their way off the beach. During the fighting in this sector, Sergeant Yahya with five

squads of infantry particularly distinguished themselves. The Turkish platoon beat back several

determined attacks on their hilltop position, until the defiant defenders disengaged under the cover

of darkness. [19]After the landings, there were so few of the Dublin Fusiliers and Munster Fusiliers

left that they were amalgamated into one unit, "The Dubsters". Only one Dubliner officer survived

the landing; overall, of the 1,012 Dubliners who landed, only 11 would survive the entire Gallipoli

campaign unscathed.

The early battles

Anzac, the landing 1915 by George Lambert, 1922 shows the landing at Anzac Cove, 25 April 1915

On the afternoon of 27 April Kemal launched a concerted attack to drive the Anzacs back to the

beach. With the support of naval gunfire, the Turks were held off throughout the night.

On 28 April, the British, now supported by the French on the right of the line, intended to capture

Krithia in what became known as the First Battle of Krithia. The plan of attack was overly complex

and poorly communicated to the commanders in the field. The troops of the 29th Division were still

exhausted and unnerved by the battle for the beaches and for Seddülbahir village, captured after

heavy fighting on 26 April. The attack ground to a halt around 6 pm with a gain of some ground but

the objective of Krithia village was not reached. After the battle, the Allied trenches lay about

halfway between the Helles headland and Krithia village. With Turkish opposition stiffening by the

day, the opportunity for the anticipated swift victory on the peninsula was disappearing. Helles, like

Anzac, became a siege. Strong Turkish counter-attacks on the nights of 1 May and 3 May were

repulsed despite breaking through the French defences.

The first attempt at an offensive at Anzac took place on the evening of 2 May when New Zealand

and Australian Division commander, General Godley, ordered the Australian 4th Infantry Brigade,

commanded by General John Monash, and the New Zealand Infantry Brigade, to attack from

Russell's Top and Quinn's Post towards Baby 700. The troops advanced a short distance during the

night and tried to dig in to hold their gains but were forced to retreat by the night of 3 May, having

suffered about 1,000 casualties.

Believing Anzac to be secure, Hamilton moved two brigades, the Australian Second Infantry

Brigade and the New Zealand Infantry Brigade, to the Helles front as reserves for the Second Battle

of Krithia starting on 6 May. This was the first major assault at Helles and gained about a quarter of

a mile on a wide front at the now customary enormous cost in casualties.

The Turks launched a major assault at Anzac on 19 May—42,000 Turks attacked 17,000

Australians and New Zealanders—but the attack miscarried. Lacking sufficient artillery and

ammunition, the Turks relied on surprise and weight of numbers for success but their preparations

were detected and the defenders were ready. When it was over the Turks had suffered about 13,000

casualties, of which 3,000 were killed.[20]In comparison, the Australian casualties were 160 killed

and 468 wounded. The Turkish losses were so severe that a truce was organized by Aubrey Herbert

and others on 24 May in order to bury the large numbers of dead lying in no man's land. This

momentary contact led to a strange camaraderie between the armies much like the Christmas truce

of 1914. It was not repeated formally.

The Sphinx, one of the battlefield's most distinctive physical landmarks

In May the British naval artillery advantage was diminished following the torpedoing of the

battleship HMS Goliath on 13 May by Turkish torpedo boat Muavenet-i Milliye. Shortly after

German submarine SM U-21 sank HMS Triumph on 25 May and HMS Majestic on 27 May.

Following these losses much of the battleship support was withdrawn and those remaining would

fire while under way, reducing their accuracy and effectiveness.

The Turkish forces in the meantime found themselves in an unenviable position, with not enough

artillery ammunition stocks to allow them to soften the Allied defenders thoroughly prior to

launching counterattacks aimed at breaking their defenses. Turkish field batteries were only able to

fire approximately 18,000 artillery rounds between early May and first week of June.[21]

By the end of the Third Battle of Krithia on 4 June, all thought of a decisive breakthrough was gone

and the plans for battle had reverted to trench warfare with objectives being measured in hundreds

of metres. Casualties ran to around 25% for both sides; the British suffering 4,500 from an attacking

force of 20,000.

In June, a fresh division, the 52nd Division, began to land at Helles in time to participate in the last

of the major Helles battles, the Battle of Gully Ravine which was launched on 28 June. This battle

advanced the British line along the left (Aegean) flank of the battlefield which resulted in a rare but

limited victory for the Allies. However, Major-General Liman von Sanders has asserted that the

British attack was repelled. He credited the successful defence to two Turkish officers, Faik Pasa

and Albay Refet.[21] Between 1 July and 5 July the Turks launched a series of desperate counterattacks against the new British line but failed to regain the lost ground. Their casualties for the

period were horrendous, estimated at in excess of 14,000.

One final British action was made at Helles on 12 July before the Allied main effort was shifted

north to Anzac. Two fresh brigades from the 52nd Division were thrown into an attack in the centre

of the line along Achi Baba Nullah (known as Bloody Valley) and sustained 30% casualties without

making any significant progress.

August offensive

Main article: Battle of Sari Bair

A trench at Lone Pine after the battle, showing Australian and Turkish dead on the parapet

The repeated failure of the Allies to capture Krithia or make any progress on the Helles front led

Hamilton to pursue a new plan for the campaign which resulted in what is now called the Battle of

Sari Bair. On the night of 6 August a fresh landing of two infantry divisions was to be made at

Suvla, five miles (8 km) north of Anzac. Meanwhile at Anzac a strong assault would be made on

the Sari Bair range by breaking out into the rough and thinly defended terrain north of the Anzac

perimeter.

The landing at Suvla Bay was only lightly opposed but the British commander, Lieutenant-General

Sir Frederick Stopford, had so diluted his early objectives that little more than the beach was seized.

Once again the Turks were able to win the race for the high ground of the Anafarta Hills thereby

rendering the Suvla front another case of static trench warfare.

The offensive was preceded on the evening of 6 August by diversionary assaults at Helles and

Anzac. At Helles, the diversion at Krithia Vineyard became another futile battle with no gains and

heavy casualties for both sides. At Anzac, an attack on the Turkish trenches at Lone Pine by the

infantry brigades of the Australian 1st Division was a rare victory for the ANZACs. However, the

main assault aimed at the peaks of Chunuk Bair and Hill 971 was less successful.

The force striking for the nearer peak of Chunuk Bair comprised the New Zealand Infantry Brigade.

It came within 500 metres of the peak by dawn on 7 August but was not able to seize the summit

until the following morning. This delay had fatal consequences for another supporting attack on the

morning of 7 August; that of the Australian 3rd Light Horse Brigade at the Nek which was to

coincide with the New Zealanders attacking back down from Chunuk Bair against the rear of the

Turkish defences. The New Zealanders held out on Chunuk Bair for two days before relief was

provided by two New Army battalions from the Wiltshire and Loyal North Lancashire Regiments.

A massive Turkish counter-attack, led in person by Mustafa Kemal, swept these two battalions from

the heights.

Of the 760 men of the New Zealanders' Wellington Battalion who reached the summit, 711 were

casualties.

Another planned attack on Hill 971 never took place. The attacking force of the Australian 4th

Infantry Brigade (General J. Monash) and an Indian brigade was defeated by the terrain and became

lost during the night. All subsequent attempts to resume the attack were easily repulsed by the

Turkish defenders at great cost to the Allies.

The Suvla landing was reinforced by the arrival of the British 53rd and 54th Divisions along with

the British 10th Division from Kitchener's New Army Divisions plus the dismounted yeomanry of

the 2nd Mounted Division. The unfortunate 29th Division was also shifted from Helles to Suvla for

one more push. The final British attempt to resuscitate the offensive came on 21 August with

attacks at Scimitar Hill and Hill 60. Control of these hills would have united the Anzac and Suvla

fronts but neither battle achieved success. When fighting at Hill 60 ceased on 29 August, the battle

for the Sari Bair heights, and indeed the battle for the peninsula, was effectively over.

Inertia set in. Alan Moorehead records that one old Turkish batman was regularly permitted to hang

his platoon's washing on the barbed wire without attracting fire, and that there was a "constant

traffic" of gifts being thrown across no-man's land: dates and sweets from the Turkish side, and

cans of beef and cigarettes from the ANZAC side.

See Also: Battle of Krithia Vineyard – Battle of Lone Pine – Battle of Chunuk Bair – Battle of the

Nek – Battle of Scimitar Hill – Battle of Hill 60

Evacuation

W Beach, Helles, on 7 January, 1916 just prior to the final evacuation

Following the failure of the August Offensive, the Gallipoli campaign entered a hiatus while the

future direction was debated. The persistent lack of progress was finally making an impression in

the United Kingdom as contrasting news of the true nature of the campaign was smuggled out by

journalists like Keith Murdoch and Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett discrediting Hamilton's performance.

Disaffected senior officers such as General Stopford also contributed to the general air of gloom.

The prospect of evacuation was raised on 11 October 1915 but Hamilton resisted the suggestion,

fearing the damage to British prestige. He was dismissed as commander shortly afterwards and

replaced by Lieutenant-General Sir Charles Monro.

The situation was complicated by the entry of Bulgaria into the war on the side of the Central

Powers. On 5 October 1915 the British opened a second Mediterranean front at Salonika which

would compete for reinforcements with Gallipoli. Also Germany would now have a direct land

route to Turkey, enabling it to supply heavy siege artillery which would devastate the Allied trench

network, especially on the confined front at Anzac.

Having reviewed the state of his command, Monro recommended evacuation. Kitchener disliked the

notion of evacuating the peninsula and made a personal visit to consult with the commanders of the

three corps; VIII Corps at Helles, IX Corps at Suvla and Anzac. The decision to evacuate was made.

Evacuation of 14 divisions in winter in proximity to the enemy would be difficult and heavy losses

were expected. The untenable nature of the Allied position was made apparent when a heavy rainstorm struck on 27 November 1915 and lasted for three days, followed by a blizzard at Suvla in

early December. The rain flooded trenches, drowning soldiers and washing unburied corpses into

the lines. The following snow killed yet more men from exposure.

Ironically the evacuation was the greatest Allied success of the campaign. Suvla and Anzac were to

be evacuated in late December, the last troops leaving before dawn on 20 December 1915. Troop

numbers had been progressively reduced since 7 December 1915 and cunning ruses, such as

William Scurry's self-firing rifle (described below), were used to fool the Turks and prevent them

discovering that the Allies were departing. At Anzac, the troops would maintain utter silence for an

hour or more until the curious Turks would venture out to inspect the trenches, whereupon the

Anzacs would open fire. As the numbers in the trenches were thinned, rifles were rigged to fire by

water dripped into a pan attached to the trigger. The entire Allied force was evacuated, but large

quanties of supplies and stores fell into Turkish hands. [22] Helles was retained in case the British

wanted to resume the offensive. However, a decision to evacuate there also was made on 27

December. The Turks were now warned of the likelihood of evacuation and mounted an attack on 6

January 1916 but were repulsed. The last British troops departed from Lancashire Landing on 9

January 1916. Amazingly, only two troops were lost during the evacuation despite the prior

warnings of 50% casualties from Sir Ian Hamilton.

Aftermath

Memorial of Anzac Cove, commemorating the loss of thousands of Turkish and Anzac soldiers in

Gallipoli.

Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives… you are now lying in the soil of a friendly country.

Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets where they lie side by

side here in this country of ours… You the mothers who sent their sons from far away countries, wipe away

your tears. Your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. Having lost their lives on this land they

have become our sons as well.

—Atatürk 1934

The Ottoman victory over the Allies at Gallipoli renewed Turkey's visions for the empire. In

Mesopotamia the Turks surrounded a British expedition at Kut Al Amara, forcing their surrender in

1916. From southern Palestine the Turks pushed into the Sinai with the aim of capturing the Suez

Canal and driving the British from Egypt. Defeat at the Battle of Romani marked the end of that

ambition and for the remainder of the war the British were on the offensive in the Middle East.

After the evacuation, Allied troops reformed and regrouped in Egypt. The Anzacs underwent a

major reorganization; the infantry were expanded and bound for the Western Front, the light horse

were reunited with their horses and formed into mounted divisions for operations in the Sinai and

Palestine. At the Battle of Beersheba they would finally achieve the decisive break-through victory

that had eluded the Allies on Gallipoli.

Amongst the generals, Gallipoli marked the end for Hamilton and Stopford but Hunter-Weston was

granted another opportunity to lead the VIII Corps on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. The

competence of Australian brigade commanders, John Monash and Henry Chauvel, would be

recognized with promotion to the command of divisions and ultimately corps. Lord Kitchener was

too popular to be punished, but he never recovered his old reputation for invincibility and was

increasingly sidelined by his colleagues until his death the following year.

On the Turkish side, the meteoric rise of Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) began at Gallipoli.

Political repercussions

The failure of the landings had significant repercussions in the UK, which began even as the battle

was still in progress. The First Sea Lord, John Fisher resigned in May after bitter conflict with

Winston Churchill over the campaign. The crisis that followed forced the Prime Minister, Herbert

Asquith to end his single-party Liberal Government and form a Coalition Government with the

Conservative Party.

Churchill was demoted from First Lord of the Admiralty as a prerequisite for Conservative entry to

the coalition; although retained in the Cabinet, he was given the sinecure job of Chancellor of the

Duchy of Lancaster, from which he resigned at the end of 1915, departing for the Western Front

where he commanded an infantry battalion early in 1916. Asquith was partly blamed for Gallipoli

and other disasters, and was overthrown in December 1916 when David Lloyd George successfully

split the Liberal Party in two. Lloyd George formed a new government, in which Churchill, active

in the House of Commons again in late 1916, was not offered a place; he was eventually appointed

Minister of Munitions in the middle of 1917, although he was not a member of the small War

Cabinet and no longer had the influence over war strategy which he had earlier enjoyed.

The Dardanelles Commission was established in 1916 to investigate the failure of the expedition. Its

final report was issued in 1919, concluding that the adventure had been badly planned and

difficulties underestimated, and that government had exacerbated problems through its

procrastination. However its censures did not damage careers measurably, further than they already

had been.[23]

Some people, such as Winston Churchill, have also argued that the landings may have helped

accelerate the genocide of the Armenian population in the Ottoman Empire during 1915.[24][25]

Conditions

The conditions at Gallipoli, on both sides, have become notorious. In the Summer, the heat was

atrocious, and in conjunction with bad sanitation, led to so many flies that eating became extremely

difficult. Corpses, left in the open, became bloated and stank. The precarious Allied bases were

poorly situated and caused supply and shelter problems. A dysentery epidemic spread through the

Allied trenches in both Anzac and Helles. Autumn and Winter brought relief from the heat, but also

led to gales, flooding and frostbite.[26]

Casualties

There were nearly half a million

casualties during the campaign,

according to the Australian

Department of Veterans' Affairs.[27] In

addition to these casualties, many

soldiers became sick due to the

unsanitary conditions, especially from

enteric fever, dysentery and diarrhea.

It is estimated that 145,000 more

British soldiers became ill during the

campaign.

Amongst the dead of the battle was

the brilliant young physicist Henry

Moseley. Also the poet Rupert

Brooke, serving with the Royal Naval

Gallipoli casualties

Source: Australian Department of Veterans' Affairs[27]

Died

Wounded Total

Total Allies 44,092

96,937 141,029

- United Kingdom 21,255

52,230 73,485

- France (estimated) 10,000

17,000 27,000

- Australia[4]

8,709

- New Zealand[4]

2,721

4,752

7,473

- India

1,358

3,421

4,779

- Newfoundland

49

93

142

19,441 28,150

Ottoman empire (estimated) 86,692

164,617 251,309

Total (both sides) 130,784

237,290 336,048

Division, died shortly before the invasion from a septic mosquito bite.

No chemical weapons were used at Gallipoli,[28] although they were used against Turkish troops in

the Middle Eastern theatre two years later during the second and third battles of Gaza in 1917.[29][30]

There were allegations that Allied forces had attacked or bombarded Turkish hospitals and hospital

ships on several occasions between the start of the campaign and September 1915. By July 1915,

there were 25 Ottoman hospitals with a total of 10,700 beds, and three hospital ships in the area.

The French Government disputed these complaints (made through the Red Cross during the war),

and the British response was that if it happened then it was accidental. Russia in turn claimed that

the Turks had attacked two of their hospital ships, Portugal and Vperiod, and the Ottoman

Government responded that the vessels had been the victims of naval mines.[31]

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) is responsible for developing and

maintaining permanent cemeteries for all Commonwealth forces—United Kingdom, Australia, New

Zealand, India, Newfoundland and others. There are 31 CWGC cemeteries on the Gallipoli

peninsula: six at Helles (plus the only solitary grave), four at Suvla and 21 at Anzac. For many of

those killed, and those who died on hospital ships and were buried at sea, there is no known grave.

These men's names are each recorded on one of five "memorials to the missing"; the Lone Pine

Memorial commemorates Australians killed in the Anzac sector; whilst the Lone Pine, Hill 60, and

Chunuk Bair Memorials commemorate New Zealanders killed at Anzac. The Twelve Tree Copse

Memorial commemorates the New Zealanders killed in the Helles sector, and British and other

troops (including Indian and Australian) who died in the Helles sector are commemorated on the

memorial at Cape Helles. British naval casualties who were lost at sea, or buried at sea, are not

recorded on these memorials, instead they are listed on memorials in the United Kingdom.[32]

There is only one French cemetery on the Gallipoli peninsula, located near Soroz Beach, which was

the French base for the duration of the campaign.

There are two more CWGC cemeteries on the Greek island of Limnos, the first in the town of

Moudros and the second in the village of Portianou. Limnos was the hospital base for the Allied

forces and most of the buried were among the wounded who didn't survive. In the Portianou village

CWGC cemetery lies a grave with the name R.J.M. Mosley on it but it's rather unlikely to be the

known physicist Henry Moseley.

Typical Gallipoli campaign epitaph at Lone Pine Cemetery

There are no large Turkish military cemeteries on the peninsula, but there are numerous memorials,

the main ones being the Çanakkale Martyrs' Memorial at Morto Bay, Cape Helles (near S Beach),

the Turkish Soldier's Memorial on Chunuk Bair and the memorial and open-air mosque for the 57th

Regiment near Quinn's Post (Bomba Sirt). There are a number of Turkish memorials and cemeteries

on the Asian shore of the Dardanelles, demonstrating the greater emphasis Turkish history places on

the victory of March 18 over the subsequent fighting on the peninsula.

See also: List of war cemeteries and memorials on the Gallipoli Peninsula

Popular influence

The significance of the Gallipoli Campaign is perhaps most strongly felt in Australia where it was

the first great conflict experienced by that nation.[33] Before Gallipoli the citizens of Australia were

confident of the superiority of the British Empire and were proud and eager to offer their service.

Gallipoli shook that confidence, and the next three years on the Western Front would damage it

further. The ANZACs are revered as heroes and, in Australia are stereotyped as typical tough

Australians betrayed by incompetent and callous British superiors, impressions re-affirmed by films

such as Peter Weir's Gallipoli, even though, according to Australian historian Les Carlyon, "the

scale of the tragedy of the Nek was mostly the work of two Australian incompetents, Hughes and

Antill."[34].

The battle also holds strong significance in New Zealand, although the common perception is not as

negative nor anti-British as that held in Australia. Nor is the battle seen as New Zealand's 'baptism

of fire' considering the contribution of New Zealand soldiers to the Boer war that was well

publicised prior to 1914. Also it must be remembered that New Zealand itself was the scene of

many fierce battles in the New Zealand land wars which had simmered on and off between the mid

1840s and the mid 1870s.

Popular Australian history asserts that while the Federation of Australia was born in 1901, the

country's true psychological independence was only achieved at Gallipoli. ANZAC Day is

commemorated every year on the landings' anniversary, 25 April, and is a national holiday in both

Australia and New Zealand.

Increasingly, Australians treat the ANZAC legend as their own, unwittingly excluding their transtasman counterparts. John Howard, former Prime Minister of Australia, famously shunned[35]the

New Zealand ANZAC service at Gallipoli in 2005, preferring instead to spend his morning at a

barbecue on the beach with Australian soldiers. In 2009, New Zealand historians noted that some

Australian children were unaware that New Zealand was a part of ANZAC.[36]

In Turkey the battle, known after the port of Çanakkale where the Royal Navy was repulsed in

March 1915, become part of the heroic story of the nation's revered founder, Mustafa Kemal

Atatürk. More widely, the ill-fated campaign is regarded as a symbol of military incompetence and

catastrophe.

There are also a couple of musical works which describe some of these events. The anti-war song

And The Band Played Waltzing Matilda, written by Eric Bogle, is about the campaign. The

bestselling novel Tell England, first published in 1922, describes the Gallipoli Campaign from the

point of view of a British junior subaltern, who saw many of his friends, including his best friend,

perish at Gallipoli.

On his 1983 album "I Haven't Changed A Bit", Slim Dusty, one of the notable Australian country

singers, published "Australia Is His Name", which occupies itself thoroughly with the incident, and

the war in particular - from an Australian point of view.

All the King's Men, a 1999 BBC film depicts the campaign. Specifically the loss of the

Sandringham company in 1915.

In 2008, the Swedish power metal/heavy metal band Sabaton released a song titled Cliffs of

Gallipoli from their album Art of War in reference to the campaign.

See also

World War I portal

Timeline of the Battle of Gallipoli

Turkish War of Independence

Gallipoli — 1981 movie

Gallipoli — 2005 documentary film

And The Band Played Waltzing Matilda — 1972 song

Gallipoli Star — Ottoman medal for gallantry

Chunuk Bair — 1991 film

Redemption by Leon Uris

Alec Campbell, the last living ANZAC at Gallipoli[37]

Notes

Footnotes

1. ^ According to historian Peter Mansfield, the British Empire troops were supported by an "Egyptian

auxiliary labour corps" of 3,000 men who performed duties such as trench digging[1]

Citations

1. ^ Mansfield, Peter (1991) A History of the Middle East, London: Penguin, p. 151.

2. ^ Dale, C. (2003-2008). "German and Austro-Hungarian Forces on Ottoman Fronts 1914-18

(follow link)". German Colonial Uniforms website.

http://www.germancolonialuniforms.co.uk/. Retrieved on 2008-12-07.

3. ^ Jung Peter, Austro-Hungarian Forces in World War 1 (Part 1),(Osprey, 2003), p.47

4. ^ a b c Dennis, Peter. "Gallipoli Campaign." Microsoft Student 2006 [DVD]. Microsoft

Corporation, 2005. Microsoft Encarta 2006. © 1993–2005 Microsoft Corporation. All rights

reserved.

5. ^ "ÇANAKKALE SAVAÞINDA 57000 ASKERÝMÝZ ÞEHÝT DÜÞTÜ" (in Turkish).

www.canakkale1915.com website. http://www.canakkale1915.com/sehitsayisi.htm.

6. ^ Bean, C.E.W. (1941) [1921]. Official Histories – First World War. Volume I – The Story

of ANZAC from the outbreak of war to the end of the first phase of the Gallipoli Campaign,

May 4, 1915 (11th ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. Cover page.

http://www.awm.gov.au/histories/chapter.asp?volume=2.

7. ^ "The Gallipoli Campaign". New Zealand History online website. Wellington: History

Group of the New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. updated 22 March 2008.

http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/war/the-gallipoli-campaign/introduction. Retrieved on 2008-1207.

8. ^ Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Web Project. "Newfoundland Regiment: Gallipoli".

Canada’s Digital Collections, Industry Canada.

http://www.heritage.nf.ca/greatwar/articles/gallipoli.html.

9. ^ a b Fromkin, 135.

10. ^ Rhodes James, 61.

11. ^ Fromkin, 151.

12. ^ Kinross, 73.

13. ^ a b Rhodes James, 74.

14. ^ Rhode James, 75.

15. ^ Rhodes James, 76

16. ^ a b Rhodes James, 77.

17. ^ "6th Gurkha Rifles". britishempire.co.uk. Luscombe, S & C.

http://www.britishempire.co.uk/forces/armyunits/gurkha/6thgurkhas.htm. Retrieved on

2009-06-19.

18. ^ "Irish battalions - major battles (Part III of XI) Helles Landings, Gallipoli, April 1915".

Royal Dublin Fusiliers: Remembering the Great War website. 2005.

http://www.greatwar.ie/mb-hel.html.

19. ^ Erickson, p. 84

20. ^ Erickson (2001), p. 87

21. ^ a b Erickson (2001), p. 89

22. ^ Erickson, p.93

23. ^ First World War.com - Encyclopedia - The Dardanelles Commission

24. ^ Robert Fisk, The Great War For Civilisation; The Conquest of the Middle East (Fourth

Estate, 2005), p. 394.

25. ^ Winston Churchill, The World Crisis: The Aftermath(London:Thornton Butterworth,

1927), p. 405.

26. ^ Les Carlyon, Gallipoli (Pan Macmillan, 2001), pp. 314, 515.

27. ^ a b ANZAC Day 2008 - The Gallipoli Campaign, Australian Department of Veterans'

Affairs. Accessed 24 March 2009.

28. ^ "Gallipoli Part V : Evacuation and the End of the Campaign". Turkey in the First World

War. http://www.turkeyswar.com/campaigns/gallipoli_cont4.htm. Retrieved on 2006-12-03.

29. ^ "Chemical warfare and the Palestine campaign in World War I". First World War.com.

http://www.firstworldwar.com/battles/gaza2.htm. Retrieved on 2006-12-03.

30. ^ "Australian Military Units — Battles of Gaza". Australian War Memorial.

http://www.awm.gov.au/units/event_136.asp. Retrieved on 2006-12-03.

31. ^ Cemalettin Taskiran (18 March 2005). "Allied Attacks On Turkish Patients & Wounded".

The Journal of the Turkish Weekly. http://www.turkishweekly.net/articles.php?id=52.

Retrieved on 2006-12-02.

32. ^ "Cape Helles Memorial to the Missing". Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

http://www.cwgc.org/search/cemetery_details.aspx?cemetery=76100&mode=1. Retrieved

on 2006-12-03.

33. ^ "'ANZAC Day' in London; King, Queen, and General Birdwood at Services in Abbey,"

New York Times. April 26, 1916.

34. ^ Les Carlyon, "Gallipoli", p.410, 2001.

35. ^ "Australian PM snubs NZ at Gallipoli", NZ Herald, 24th April 2005.

36. ^ "Aussies forget the NZ in ANZAC", AAP.com.au

37. ^ Shaw, John. "Alec Campbell, Last Anzac at Gallipoli, Dies at 103," New York Times; 20

May 2002

References

Carlyon, Les (2001). Gallipoli. Doubleday / Pan Macmillan divisions of Random house.

ISBN 0385 604750.

Cowan, James (1926). The Maoris in the Great War (including Gallipoli).

http://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-CowMaor.html.

Erickson, Edward J. (2001) [2000]. Ordered to die: a history of the Ottoman army in the

First World War. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing. ISBN 0313315167.

Gilbert, Martin (2004). The First World War: a complete history. New York: Henry Holt

and Co.. ISBN 0-8050-7617-4.

Haythornthwaite, Philip J. (1991). Gallipoli 1915, Frontal Assault on Turkey. Campaign

Series #8. Osprey.

James, Robert Rhodes (1995). Gallipoli: a British historian's view. Parkville, Vic.: Dept. of

History, University of Melbourne. ISBN 0-7325-1219-0.

Tyquin, M. (1993). Gallipoli: the Medical War. Sydney: University of New South Wales

Press.

Waite, Colonel Fred (1919). The New Zealanders at Gallipoli.

http://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-WaiNewZ.html.

"Gallipoli". Despatches from Gallipoli website. National Library of Australia.

http://www.nla.gov.au/gallipolidespatches/1-gallipoli.html.

Further reading

Kyle, Roy, (2003) "An Anzac's Story". Camberwell, Penguin, ISBN 0-143-00187-6.

Ralph, May, (2003)"Glory Is No Compensation". Silver Link Publishing ISBN 1-85794214-0 or visit http://www.kingsownbordermuseum.btik.com/p_Books.ikml

External links

Gallipoli Original reports from The Times

ÇANAKKALE Martyrs Memorial And The National Park

Scanned PDF volumes from the Australian War Memorial of the Official History of

Australia in the War of 1914-1918:

o Bean, C.E.W. (1941) [1921]. Official Histories – First World War. Volume I – The

Story of ANZAC from 4 May, 1915, to the evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula

(11th ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial.

http://www.awm.gov.au/histories/chapter.asp?volume=2.

o Bean, C.E.W. (1941) [1924]. Official Histories – First World War. Volume II – The

Story of ANZAC from the outbreak of war to the end of the first phase of the

Gallipoli Campaign, May 4, 1915 (11th ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial.

http://www.awm.gov.au/histories/chapter.asp?volume=3.

Turkish site about the Battle of Gallipoli

Visit Gallipoli: Australian site about Gallipoli and the Anzacs, includes previously

unpublished photographs, artworks and documents from Government archives. A site by the

Australian Department of Veterans' Affairs.

…in bidding 'Au revoir' to our honourable foes …

Dardanelles Campaign rare photos

Gallipoli Despatches

Gallipoli pages of 'Turkey in WW1' web site

Allied Disaster

Illustrated account of a visit to the Gallipoli battlefields at 'Battlefields Europe'.

New Zealanders at Gallipoli

Guide to Gallipoli on www.anzac.govt.nz. Includes interactive panoramas.

Five Months at Anzac, by Joseph Lievesley Beeston

Memoirs & Diaries: The Evacuation of Suvla Bay

Poems from Anzac Cove by Gunner F.E. Westbrook 1915

Royal Engineers Museum Royal Engineers and the Gallipoli Expedition (1915–16)

Enver Pasha

Carlyon, Les (11 November 2004). "Australian War Memorial Anniversary Oration:

Gallipoli in a Nation's Remembrance (soundtrack and text)". Australian government War

Memorial. http://www.awm.gov.au/events/talks/oration2004.asp. Retrieved on 2008-12-07.

Address by Les Carlyon about the effects of Gallipoli

[1] For Information On 1st Battalion Border Regiment at Gallipoli 1915

http://www.kingsownbordermuseum.btik.com/p_Home.ikml

Naval operations in the Dardanelles Campaign

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Naval Operations in the Dardanelles Campaign

Part of Gallipoli Campaign in WWI

The last moments of the French battleship Bouvet, 18

March 1915

Date

Location

Result

19 February 1915 – 9 January

1916

Dardanelles, Turkey

Decisive Turkish victory

Belligerents

British Empire

France

Australia

Russia

Ottoman Empire

Germany

Commanders

Fuad Paşa

Sackville Carden

Cevat Bey

John de Robeck

Otto Liman von

Émile Guépratte

Sanders

Strength

31 battleships

Various mines and forts;

3 battlecruisers

24 cruisers

25 destroyers

8 monitors

14 submarines

50+ transports

otherwise Unknown

Casualties and losses

6 battleships sunk

3 battleships damaged

2 battleships

1 battlecruiser damaged

1 minelayer

1 destroyer sunk

Casualties:

8 submarines lost

253,000

Casualties:

252,000

[hide]

v•d•e

Gallipoli Campaign

Naval operations – Anzac Cove – Helles – 1st Krithia – 2nd Krithia – 3rd Krithia – Gully Ravine –

Sari Bair – Krithia Vineyard – Lone Pine – Suvla – The Nek – Chunuk Bair – Scimitar Hill –

Hill 60

The naval operations in the Dardanelles Campaign of the First World War were mainly carried

out by the Royal Navy with substantial support from the French and minor contributions from

Russia and Australia. The Dardanelles Campaign began as a purely naval operation. When that

failed to overcome Turkish defences, an invasion of the Gallipoli peninsula was launched in which

naval forces were heavily involved. Throughout the campaign, attempts were made by submarines

to pass through the Dardanelles and disrupt Ottoman Empire shipping in the Sea of Marmara.

Contents

1 Prelude

o 1.1 Closure of the Dardanelles

o 1.2 Divided responsibilities

2 Forcing the straits

3 The Battle of March 18

o 3.1 Aftermath

o 3.2 Further Attempts

4 Submarine operations

5 Supporting the army

6 See also

7 References

o 7.1 Notes

8 External links

Prelude

At the outbreak of World War I, the Ottoman Empire was an unaligned power. While Britain had a

long history of interest in the region, Germany had been most active in cultivating a relationship

with the Ottomans. At the outbreak of war, the British seized two battleships constructed for the

Ottoman Empire which were still in British shipyards.[1] In response, Germany made a gift of two

ships, the battlecruiser Goeben and the light cruiser Breslau, as replacements. While still operated

by their German crews, these ships, renamed Yavuz Sultan Selim and Midilli respectively, became

the backbone of the Ottoman navy. Through possession of the Goeben, the Ottoman Empire

controlled the most powerful ship in the Black Sea in 1914.[2]

Closure of the Dardanelles

In October 1914, the Ottomans closed the Dardanelles to Allied shipping. This followed an incident

on September 27 when the British Dardanelles squadron had seized a Turkish torpedo boat. The

actual decision to close the strait seems to have been taken by German military advisors stationed in

the Dardanelles without reference to the Turkish government.[3] On October 28, the Turkish fleet,

led by the Goeben, began raiding Russian assets in the Black Sea. Odessa and Sevastopol were

bombarded, a minelayer and gunboat were sunk. The real aim of the attack—putting the Russian

Black Sea fleet out of commission—was not accomplished. Russia declared war on the Ottoman

Empire on November 2, and the British followed suit on November 6. An unsuccessful Ottoman

attack on Russia through the Caucasus Mountains was launched in December (Battle of Sarıkamış),

leading the Russians to call for aid from Britain in January 1915.[4]

Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, had entertained plans of capturing the

Dardanelles as early as September 1914. In a new year review submitted to the prime minister,

Herbert Asquith, he had outlined two possible new fronts against the Germans, intended to break

the stalemate and accompanying enormous loss of life which had rapidly set in on the western front.

The first possibility, which was then his favoured option, was an invasion of Schleswig-Holstein by

sea, allowing Denmark to join the allies and give Russia a supply route via the Baltic sea. The other

was an attack on the Dardanelles, which again would give Russia a supply route and might

encourage Bulgaria and Romania to join the allied side. The Russian plea for assistance, coupled

with a perception of the Ottoman Empire as a weak enemy ("the Sick man of Europe"), made the

prospect of a campaign in the Dardanelles seem appealing.[5]

Divided responsibilities

First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill and First Sea Lord Fisher, 1914

Matters were complicated for Churchill by the choice of First Sea Lord, who was the most senior

admiral in charge of running the navy. Churchill had appointed Prince Louis of Battenberg in 1912.

He was obliged to replace Battenberg because of public feeling against Germans — Battenberg had

become a British citizen when he joined the navy at the age of 14, but he spoke with a German

accent.[6] His choice was to recall the 73 year old Admiral Fisher, who had retired as First Sea Lord

in 1910. Fisher was regarded as brilliant, but somewhat in decline from advancing age. More

immediately a problem for Churchill, he was a forceful personality accustomed to directing the

Admiralty himself, and being supported in his decisions by the political First Lord rather than

taking orders from him.[7]

Fisher was appointed at the end of October 1914 and favoured a new campaign in northern Europe,

which perhaps reflected the navy's traditional concern of controlling Channel waters.[8] He

reluctantly agreed to advance the plan for a naval action in the Dardanelles, but afterwards

maintained that he had never supported it,[9] and had always believed a naval action would have to

be accompanied by a land force. Churchill and Fisher continually quarreled throughout the

campaign, and Fisher finally resigned on 15 May 1915 after repeated threats to do so. Fisher wrote

about Churchill that: He is always convincing me.[10] Fisher's relationship with Churchill had always

been complex and his abrupt resignation was no exception. Fisher's resignation, on top of poor

progress in the campaign, precipitated the fall of the government and Churchill's replacement as

First Lord, so neither man gained control of the Admiralty. Ironically, although they could not

agree, both respected the other and would not have wished that outcome.[citation needed]

On January 11, at Churchill's request, the commander of the Royal Navy's Mediterranean Squadron,

Vice Admiral S.H. Carden proposed a plan for forcing the Dardanelles using battleships,

submarines and minesweepers. On January 13, the British War Council approved the plan, and

Carden was supplied with additional pre-Dreadnought battleships, the battleship HMS Queen

Elizabeth and the battlecruiser HMS Inflexible. France supplied a squadron which included four

pre-Dreadnought battleships, while Russia provided a single light cruiser, the Askold.

The operation was originally intended to be purely naval due to a lack of available troops but, by

early February, it was decided that more regular infantry was needed. Contingents of Royal Marines

were to be supplemented by the last unallocated regular division, the British 29th Division. It was

dispatched to Egypt, to join Australian and New Zealand troops which were already undergoing

training. At the outset of the operation, the expected role of the infantry was to be the occupation of

Istanbul; the taking of the straits was to be accomplished by the Entente naval forces.

Forcing the straits

On November 3, 1914, Churchill ordered the first British attack on the Dardanelles following the

opening of hostilities between Turkey and Russia. The British attack was carried out by

battlecruisers of Carden's Mediterranean Squadron, Indomitable and Indefatigable, as well as the

obsolete French battleships Suffren and Vérité. This attack actually took place before a formal

declaration of war had been made by Britain against the Ottoman Empire.

The intention of the attack was to test the fortifications and measure the Turkish response. The

results were deceptively encouraging. In a twenty minute bombardment, a single shell struck the

magazine of the fort at Sedd el Bahr at the tip of the Gallipoli peninsula, displacing (but not

destroying) 10 guns and killing 86 Turkish soldiers. Total casualties during the attack were 150, of

which 40 were German. The most significant consequence was that the attention of the Turks was

drawn to strengthening their defences, and they set about expanding the mine field.[11]

The Dardanelles defences in February/March 1915, showing minefields, anti-submarine nets and

major gun batteries.

The Dardanelles were defended by a system of fortified and mobile artillery arranged as the

"Outer", "Intermediate" and "Inner" defences. While the outer defences lay at the entrance to the

straits and would prove vulnerable to bombardment and raiding, the inner defences covered the

Narrows, the narrowest point of the straits near Çanakkale. Beyond the inner defences, the straits

were virtually undefended. However, the foundation of the straits defences were a series of 10

minefields, laid across the straits near the Narrows and containing a total of 370 mines.

What was to become the Battle of Gallipoli, a 10-month battle of attrition, began at 7.30am on

February 19, 1915. Two destroyers were sent in to probe the straits. The first shot was fired from

Kumkale by the Orhaniye Tepe battery's 24 cm Krupp guns at 7.58am. The battleships Cornwallis

and Vengeance moved in to engage the forts and the first British shot of the campaign proper was

fired at 9.51am by Cornwallis. The day's bombardment lacked the spectacular results of the

November 3 test.

HMS Canopus fires a salvo from her 12-inch (30.5 cm) guns against Turkish forts in the

Dardanelles.

Another attempt was made on February 25. This time the Turks evacuated the outer defences and

the fleet entered the straits to engage the intermediate defences. Demolition parties of Royal

Marines raided the Sedd el Bahr and Kum Kale forts, meeting little opposition. On March 1, four

battleships bombarded the intermediate defences.

Little progress was made clearing the minefields. The minesweepers, commanded by Carden's chief

of staff, Roger Keyes, were merely un-armoured trawlers manned by their civilian crews who were

unwilling to work while under fire. The strong current in the straits further hampered the sweeping

process. This lack of progress by the fleet strengthened the Turkish resolve which had wavered at

the start of the offensive. On March 4, raids on the outer defences were resisted, leaving 23 British

marines dead.

The Queen Elizabeth was called on to engage the inner defences, at first from the Aegean coast near

Gaba Tepe, firing across the peninsula, and later from within the straits. On the night of March 13,

the cruiser HMS Amethyst led six minesweepers in an attempt to clear the mines. Four of the

trawlers were hit and the Amethyst was badly damaged with 19 stokers killed from a single hit.

On March 15, the admiralty informed Carden that they agreed to his plan for a further all out attack

by daylight, with the minesweepers operating under the direct protection of the entire fleet. Carden

was taken ill the same day, and had to be replaced by Rear Admiral John de Robeck. A gunnery

officer noted in his diary that de Robeck had already expressed misgivings with the likelihood of

being able to silence the Turkish guns by bombardment, and that this view was widely held on

board the ship.[12]

The Battle of March 18

The event that decided the battle took place on the night of March 8 when the Turkish minelayer

Nusret laid a line of mines in Eren Köy Bay, a wide bay along the Asian shore just inside the

entrance to the straits. The Turks had noticed the British ships turned to starboard into the bay when

withdrawing. The new line of between 20 and 26 mines ran parallel to the shore, were moored at

2.5 fathoms (4.5 m) and spaced about 100 yards (91 m) apart. The clear water meant that the mines

could have been seen through the water by spotter planes.[13]

The British plan for March 18 was to silence the defences guarding the first five lines of mines

which would be cleared overnight by the minesweepers. The next day the remaining defences

around the Narrows would be defeated and the last five minefields would be cleared.

The battleships were arranged in three lines, two British and one French, with supporting ships on

the flanks and two ships in reserve.

Battle lines of March 18

Grey background: Severe damage, Red background: Sunk

Line A

HMS Queen

Elizabeth

HMS Agamemnon

HMS Lord

Nelson

HMS

Inflexible

French Line B

Gaulois

Charlemagne

Bouvet

Suffren

British Line B

HMS Vengeance

HMS Irresistible

HMS Albion

HMS Ocean

Supporting

ships

HMS Majestic

HMS Prince

George

HMS Swiftsure

HMS Triumph

Reserve

HMS Canopus

HMS Cornwallis

The first British line opened fire from Eren Köy Bay around 11am. Shortly after noon, de Robeck

ordered the French line to pass through and close on the Narrows forts. The Turkish fire began to

take its toll with Gaulois, Suffren, Agamemnon and Inflexible all suffering hits. While the naval fire

had not destroyed the Turkish batteries, it had succeeded in temporarily reducing their fire. By

1.25pm the Turkish defences were mostly silent so de Robeck decided to withdraw the French line

and bring forward the second British line as well as Swiftsure and Majestic.

At 1.54pm Bouvet, having made a turn to starboard into Erenköy Bay, struck a mine, capsized and

sank within a couple of minutes, killing 600 men. The initial British reaction was that a shell had

struck her magazine or she had been torpedoed. Most reports state that they remained unaware of

the minefield, however mines in the string had been spotted earlier that morning, and their sighting

relayed to Admiral de Robeck.[citation needed] Civilian trawlers acting as minesweepers in front of line

'A' discovered and destroyed three mines in an area thought to be clear, before the civilian crews

withdrew under fire. This information was not passed on to de Robeck.[14]

Irresistible abandoned and sinking.

The British pressed on with the attack. Around 4pm Inflexible began to withdraw and struck a mine

near where Bouvet went down, killing 30 men. The battlecruiser remained afloat and eventually

beached on the island of Bozcaada (Tenedos).

Irresistible was the next to be mined. As she began to drift helplessly, the crew were taken off. De

Robeck told Ocean to take Irresistible under tow but the water was deemed too shallow to make an

approach. Finally at 6.05pm Ocean struck a mine which jammed the steering gear leaving her

likewise helpless. The abandoned battleships were still floating when the British withdrew. A

destroyer commanded by Commodore Roger Keyes returned later to attempt either to tow away or

sink the stricken vessels but despite searching for four hours, there was no sign of them. Keyes

reported:

The fear of their fire was actually the deciding factor of the fortunes of the day. For five hours the [destroyer]

Wear and picket boats had experienced, quite unperturbed and without any loss, a far more intense fire from

them than the sweepers encountered... the latter could not be induced to face it, and sweep ahead of the ships

in 'B' line.[14] ...I had the almost indelible impression that we were in the presence of a beaten foe. I thought

he was beaten at 2 pm. I knew he was beaten at 4 PM — and at midnight I knew with still greater clarity that

he was absolutely beaten; and it only remained for us to organise a proper sweeping force and devise some

means of dealing with drifting mines to reap the fruits of our efforts.[15]

By contrast, Commander Isham Worsley Gibson wrote:

This is just what one might expect, & what we really did more or less. Every book on war ever written

always states the fact that politicians interfering with Commanders in the field always lead to disaster but

still they think they are born strategists & know alls & do it again & again.[16]

Aftermath

March 18 was a significant victory for Turkey. Nevertheless, there were calls amongst the British,

particularly from Churchill, to press on with the naval attack. De Robeck advised on 20 March that

he was reorganising his minesweepers, suggesting he intended to resume the attack, and Churchill

responded that he was sending four replacement ships. With the exception of the Inflexible, the

ships that were lost or damaged were old, ill-equipped for modern naval combat and had been

chosen for the expedition precisely because they were expendable. The Turkish forts had nearly

exhausted their ammunition so that if the naval attack had resumed, the Allies would have met little

opposition from the guns. Moreover the crews of the sunken battleships had replaced the civilians

on the trawler minesweepers, making them much more willing to keep sweeping under fire, and the

fleet had several modern destroyers fitted with 1 1/2" minesweeping hawsers that could have

handled the task with ease. The American ambassador to Turkey, Henry Morgenthau, reported that

Istanbul expected to be attacked and that the Turks felt they could only hold out for a few hours if

the attack had resumed on the 19th.[17] Further, he thought that Turkey itself might well disintegrate

as a state once the capital fell.[18]

It must be noted that the main mine fields at the narrows, over ten layers deep were still fully intact.

Furthermore, they were very well protected by the smaller shore guns that had not seen any action

on March 18th. These and other defenses further in the straight had not exhausted their ammunition

and resources yet. It was not a given that one more push by the fleet would have resulted in passage

to Marmara Sea.

Sir Roger Keyes, Vice-Admiral De Robeck, Sir Ian Hamilton, General Braithwaite

Churchill had anticipated losses and considered them a necessary tactical price. In June 1915, he

discussed the campaign with the war correspondent Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, who had returned to

London to deliver uncensored reports. Ashmead-Bartlett was incensed at the loss of ships and lives

but Churchill responded: That is not the point! They ought to have gone on. What did it matter if

more ships were lost? The ships were old and useless.[19] To place the losses into perspective, the

Navy ordered 600 new ships during the period Admiral Fisher was First Sea Lord, approximately

corresponding with the length of the Dardanelles campaign.[10]