Copyright, Performance Licenses, and You

advertisement

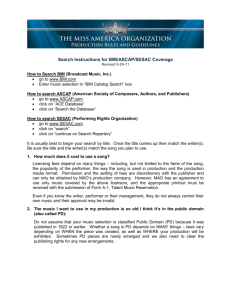

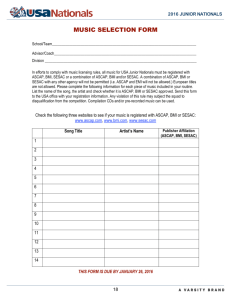

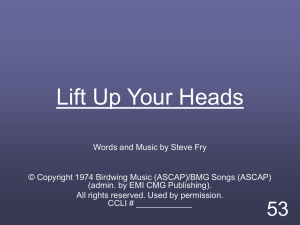

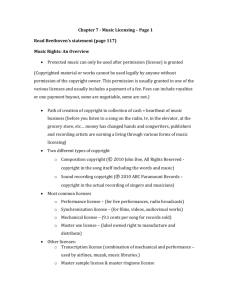

Copyright, Performance Licenses, and You By Lyn Liston Do you know that you need to obtain a license when you perform contemporary music? Many musicians are unaware that performing a copyrighted work without obtaining a license is a form of copyright infringement. In this article, I will explain some basics about copyright law and how you can go about protecting the rights of your fellow musicians, the composers themselves. Many performers assume that purchasing music automatically gives them the right to perform it. This is not the case if the work is in copyright. Just as you don’t have a right to photocopy it without permission; you also don’t have a right to perform it publicly without permission. If you want to gain permission to perform it, you have to get a license. Licensing Basics So, what does a performer need to know about licensing? I think the best place to start is with the copyright law. There are six rights that the U.S. government gives exclusively to copyright holders—usually the composer or the publisher. They are: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. the right to reproduce the work in copies or phonorecords (i.e., CDs, tapes, etc.); the right to prepare derivative works based upon the work; the right to distribute copies or phonorecords of the work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending; the right to perform the work publicly, in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and motion pictures and other audiovisual works; the right to display the copyrighted work publicly, in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and pictorial, graphic, or sculptural works, including the individual images of a motion picture or other audiovisual work; and in the case of sound recordings, the right to perform the work publicly by means of a digital audio transmission. Right Number 4 above covers public performances. The copyright owner has the exclusive right to perform the work publicly and s/he has the power to grant others the right to perform it, too. Rights are granted, in the U.S. and in most other countries, via a performance license. There are two types of performing rights licenses: (1) small or “concert” rights, and (2) “grand” rights for dramatic works (performances of operas, ballets, modern dance, incidental music, etc.). What constitutes a public performance? The U.S. Copyright Law defines a public performance of a work as follows: (1) to perform or display it at a place open to the public or at any place where a substantial number of persons outside of a normal circle of a family and its social acquaintances is gathered; or (2) to transmit or otherwise communicate a performance or display of the work to a place specified by clause (1) or to the public, by means of any device or process, whether the members of the public capable of receiving the performance or display receive it in the same place or in separate places and at the same time or at different times. So if you’re performing copyrighted music in a concert hall, a café, a park, a church (except during an actual religious service—those are exempt), or a college auditorium, you must obtain a license if the concert hall or presenter has not done so. Even if it’s a free concert or you’re not getting paid, you’re still using the music. Where do you go to get a license? Usually the kind of license a chamber ensemble needs is called a small or “concert” rights license. You can obtain one from a performing rights society. In the U.S., we have three performing rights societies: ASCAP (American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers), BMI (Broadcast Music, Inc.), and SESAC (Society of European Stage Authors & Composers). Much of the contemporary music that is likely to be performed by CMA members will be registered with ASCAP or BMI. These three organizations were formed, in part, to make it easier for composers and publishers to keep track of performances. It is impossible for a composer or a publisher to license all the recital halls, churches, and other possible venues. In addition, public performances extend to radio and television broadcasts, restaurants, telephone on-hold music, the internet, etc. Unlike composers and publishers, performing rights societies are set up to grant licenses. One advantage of contacting ASCAP and BMI is their staffs are advocates for contemporary music, and they want you to perform it. They are not the copyright police! They are there to help and can often be a good friend to a performing ensemble. In many cases, the performance venue will already have what is known as a blanket license, which in most cases covers the performances that they present during a specified period. In all cases, however, find out whether or not your concert is already covered. The law makes you responsible for getting a license, so it’s in your best interest to check. When you ask, find out if your concert is covered, not just whether the hall has ASCAP and BMI licenses. If you find that you do need to get a license for a specific performance or a series of performances, then contact ASCAP and BMI to find out the necessary steps to get one. If you have multiple performances, you may be able to get a license that covers all of them. The staff at ASCAP and BMI will help you determine what kind of license is right for you. It’s easy to find out whether a particular work is registered with ASCAP, BMI, or SESAC. Just go to their websites (www.ascap.com, www.bmi.com, or www.sesac.com) and follow the instructions. Note that, in most cases, a work cannot be registered with more than one performing rights society at a time. In addition, most composers register their complete catalogs with only one performing rights society. The exceptions to this are rare. Grand Rights There may be times when you need to obtain a “grand rights” license. These are issued for dramatic performances. For example, if you have hired dancers for a performance, if you are presenting a chamber opera, or if your concert involves any kind of dramatic presentation in conjunction with music, you need to go directly to the copyright holder to obtain a license. In this country, performing rights societies do not license these performances. The copyright holder could be the publisher or composer. Arrangements and Transcriptions Another issue involving rights that is often not obvious to ensembles is the right to create and perform an arrangement or transcription of a work in copyright. These are covered under Right Number 2 above. Only the copyright holder has the right to create a derivative work, but s/he or the publisher may give you the right to create it. You will have to contact them directly. The only exception to this is in the case of a commercial recording. With phonorecord rights, you can actually make a commercial recording of a derivative work without being required to get permission from the copyright holder, provided you have obtained a mechanical license (covered under Right Number 1). It’s always a good idea, however, to check with the copyright holder. Additional Information The information above does not cover all possibilities and exceptions, so please consider this a starting point in learning about performing rights licenses. For more information on copyright law, visit the website of the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov. The Copyright Office has an extensive section within this site that includes detailed information on the copyright law. ASCAP and BMI have put their licenses online on their websites, and I encourage you to contact these organizations directly for more information. Lyn Liston is the Director of New Music Information Services at the American Music Center. ### Contact the American Music Center: for additional information about any kind of licensing; if you need to contact a composer or publisher; for advice on repertoire selection; if you need assistance in finding out with which performing rights society a particular work is registered. Please feel free to contact the American Music Center at info@amc.net, or (212) 366-5260 x11.