Reducing the use of High Acquisition Cost (HAC) Proton Pump

advertisement

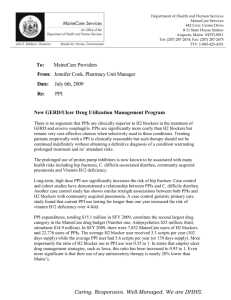

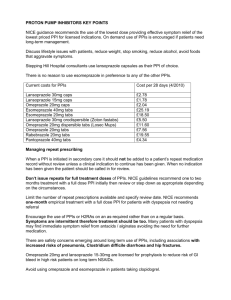

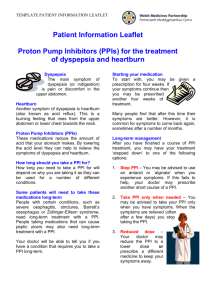

Clinical Effectiveness Prescribing Programme (CEPP) All Wales Audit/Review Pack: Reducing the use of High Acquisition Cost (HAC) Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPI) 2011-2013 Quality and Cost Improvement Toolkit This audit was endorsed by the All Wales Medicines Strategy Group (AWMSG) at their meeting on the 16th March 2011 and forms part of the Clinical Effectiveness Prescribing Programme, formerly known as the Prescribing Incentive Scheme. Please send the Data Summary Sheets 1-2 and the Practice Review Sheet to your local Medicines Management team on or before the 31st October 2011. Your Medicines Management team will compile the local information and forward to the Welsh Medicines Partnership (wmp@wales.nhs.uk) who will provide a national perspective (which is required by the Welsh Assembly Government). Contents Page Background 3 Purpose and Summary of Document 3 Introduction 4 Useful Resources 7 Aim of the Audit 7 Audit Criteria 7 Review Criteria 8 Method 8 Results and Reflection 10 References 11 Sample Individual PPI Patient Collection Sheet 12 Collated Patient Data Sheet 13 Data Summary Sheet (1) 14 Data Summary Sheet (2) 15 Practice Review Sheet 16 Appendix A – Sample Selection 17 2 Clinical Effectiveness Prescribing Programme (CEPP) All Wales Audit/Review Pack: Reducing the use of High Acquisition Cost (HAC) Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPI) 2011-2013 Quality and Cost Improvement Toolkit Background: Quality improvement toolkits have been developed to assist general practices in collating and auditing information. These are produced with reference to evidence-based practice and Welsh priorities. They should be seen as good practice and are intended to improve data quality and aid development within the practice. Improvements in practice will be optimised by multidisciplinary involvement in the audit and team discussion of the results. It is recommended that action plans implemented following this audit are reviewed within six months and re-audit undertaken if possible in 6-12 months. Purpose and Summary of Document: The following audit/review has been developed by the Welsh Medicines Partnership. This document is for use by primary care general practitioners to highlight prescribing and cost-effectiveness issues with PPIs. It will be available via the AWMSG website. The audit will be available from April 2011, so that it can be used as one of the CEPP national audits for the following two years (2011–2013). Also included is a practice review section designed to encourage a whole practice response to the audit findings and an evaluation of the quality and usefulness of the audit itself. 3 1. Introduction 1.1 Indications for use Dyspepsia is defined as any symptom of the upper gastrointestinal tract, present for four weeks or more, including upper abdominal pain or discomfort, heartburn, acid reflux, nausea or vomiting1. Of the adult population, 40% will have symptoms of dyspepsia, leading to 5% consulting their GP, and 1% being referred for endoscopy. In patients with symptoms severe enough to be referred for endoscopy, 40% will have functional dyspepsia, 40% will have gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) and 13% some sort of ulcer1. PPIs are licensed and prescribed for a range of indications including1,2: Uninvestigated and non-ulcer (or functional) dyspepsia GORD Peptic ulcers Eradication of Helicobacter pylori (in combination with antibiotics) Control of excessive acid secretion in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome Prevention and treatment of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) associated ulcers. In addition, other indications for PPIs, encompassing unlicensed uses, that are common in hospital settings include the reduction of re-bleeding episodes after treatment of severe peptic ulcer bleeding, prophylaxis of acid aspiration during general anaesthesia and stress ulcer prophylaxis2. 1.2 Prescribing across Wales PPI use is continuing to increase across Wales. One possible explanation for this is that they are continued when they are no longer indicated2, as for many indications, such as peptic ulcer disease, treatment courses are intended for short term use only1. It has also been suggested that a reduction in cost, together with reduced concerns of their safety has led to a more liberal use of PPIs for a wide variety of upper gastrointestinal symptoms with a substantial proportion, if not majority, of patients now prescribed PPIs have no true indication for treatment3. Items Per 1000 PU's National GP (Proton Pump Inhibitors) 250.00 National GP 200.00 ABMU - GP Aneurin Bevan - GP 150.00 Betsi Cadwaladr Uni - GP 100.00 Cardiff And Vale Uni - GP 50.00 Cwm Taf - GP 0.00 20 07 1 20 2 08 0 20 3 08 0 20 6 08 20 09 08 1 20 2 09 0 20 3 09 20 06 09 0 20 9 09 1 20 2 10 0 20 3 10 06 Hywel Dda - GP Powys Teaching - GP The June 2010 average All Wales figure for the PPI National Prescribing Indicator was 5208.51 DDD* per 1,000 patient units (PUs) ranging from 4,123.50 to 6,915.33 across the 22 former Local Health Board (LHB) localities4. *The Defined Daily Dose (DDD) is a measure of prescribing volume maintained by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and represents the assumed average maintenance dose per day for a drug used for its main indication in adults. It allows prescribing activity to be compared fairly and accurately across localities. 4 1.3 Prescribing costs There has been a decrease in the overall costs of PPIs over the past few years due to the availability and reduction in costs of generic omeprazole 10mg and 20mg capsules, lansoprazole 15mg and 30mg capsules, and more recently pantoprazole 20mg and 40mg tablets. Other formulations of omeprazole and lansoprazole (e.g. generic tablets and dispersible tablets), liquid specials and branded preparations are considerably more expensive, as are other PPIs such as esomeprazole (Nexium®) and rabeprazole (Pariet®). Although only 14% of the items prescribed in Wales are for the more costly preparations they account for 37% of the cost (quarter ending Sept 10)4. In the former 22 LHB localities, low acquisition cost (LAC) PPIs account for between 81% and 90% of the items prescribed (quarter ending Sept 10). For a similar indicator in England, the upper quartile of Trusts are currently achieving 92%5. Increasing the All Wales percentage of LAC PPIs to 92%, assuming the number of prescription items remain the same, would potentially save over £1.5 million per annum (extrapolated data for the quarter ending Sept 10)4. There is no evidence that, at equivalent doses, any one PPI is more effective at healing oesophagitis than another1. Newer PPIs offer no advantages in terms of clinical efficacy, and there is less evidence for long term safety6. They are also considerably more expensive, and NICE guidelines recommend that the least expensive PPI should be used1. Therefore, generic lansoprazole and omeprazole* capsules or pantoprazole tablets should be used as first line therapies. PPI Omeprazole Lansoprazole Pantoprazole Usual Doses for PPIs 6 High Dose Full Dose * 40mg 20mg 30mg 40mg Low Dose 10mg 15mg 20mg Rabeprazole Esomeprazole 40mg 10mg - 20mg 20mg * using 2x20mg capsules of omeprazole is more cost effective than 40mg capsules7 1.4 Emerging concerns with PPI use Although PPIs are generally well tolerated, there is emerging evidence with regards to the potential consequences of potent acid suppression8. The incidence of short-term adverse events is low. There is, however, evidence to suggest that some serious adverse effects may be linked with long term PPI use, and although some of the evidence is conflicting, safety concerns have been raised2. Adverse effects investigated include increased risk of osteoporotic fractures of the hip, wrist and spine, Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), both hospital-associated and communityacquired pneumonia, and a possible association with colorectal cancer2,8. 1.5 Stepping down and/or stopping PPIs There is a potential risk of psychological dependence on PPIs and it has been recommended by NICE that patients on these medications long term are reviewed on an annual basis1. During this review NICE guidance suggests that where appropriate patients should be: Encouraged to try stepping down or stopping treatment Offered lifestyle advice Advised on how to avoid precipitants that contribute to their dyspepsia. Patients often find it difficult to step-down or step-off PPI therapy, and evidence now suggests that PPI withdrawal may lead to rebound acid hypersecretion. A study by Reimer et al found that eight weeks of PPI therapy induced acid-related symptoms in healthy volunteers after withdrawal of therapy9. This may have implications in clinical practice. If a similar increase in such symptoms 5 is seen in patients on withdrawal of PPI, this will lead to reliance on these medications and an increased requirement for long term treatment2,3. NICE recommends that when patients are stepping down or stepping off therapy, a return to self care may be appropriate, with antacid/alginate therapy taken as required1. 1.6 General prescribing points Prescribers are reminded that: PPIs should only be started or continued where there is a valid documented indication. The use of PPIs for mild or vague symptoms and any ‘diagnostic’ use must be short term2. All patients on a long term PPI should have an annual review to discuss continuing need for medication and/or stepping down treatment, unless there is an underlying condition or co-medication that necessitates ongoing treatment10. NICE recommendations state that the least expensive PPI should be used1. There is no evidence that there is any difference in clinical efficacy between PPIs at equivalent doses6, although prescribers should be aware that there are some slight variations in the indications for use, interactions and cautions11. Generic omeprazole and lansoprazole capsules or pantoprazole tablets should be used as first-line therapies. Some medications can contribute to the symptoms of dyspepsia (examples include calcium antagonists, nitrates, theophyllines, bisphosphonates and NSAIDs)10. Existing medication should be reviewed, and if a causative medication is identified withdrawal should be considered6. Initial therapeutic strategies for dyspepsia are empirical treatment with a PPI or testing for and treating H. pylori. There is currently insufficient evidence to guide which should be offered first10. A two week washout period following PPI use is necessary before testing for H. pylori with a breath test or stool antigen test10. Patients diagnosed with peptic ulcer should also be tested and treated for H. pylori; however, there is currently no evidence that H. pylori should be investigated in patients with GORD10. NICE recommends that a PPI (with the lowest acquisition cost) should be co-prescribed in patients treated with an oral NSAID/COX-2 inhibitor12. Before using an NSAID which requires concurrent use of a PPI, it should be established whether all other strategies to optimise pain control have been considered8. PPI withdrawal may induce rebound acid hypersecretion2,8. This may explain the continued use of PPIs in patients and the inability to discontinue treatment. Patients should therefore be informed of this potential risk when both stepping down and stopping therapy. Consideration should also be given to implementing strategies that may reduce rebound acid hypersecretion such as intermittent dosing (where clinically appropriate), or the use of antacid/alginate therapy8. In general PPIs are well tolerated. There have however been a number of recent reports which have documented concerns about possible adverse events relating to their use. These include a small increase in the risk of both hospital-acquired and community-acquired pneumonia13,14 and possible increase in fracture risk15. This should be taken into consideration when prescribing a PPI in those patients with other risk factors for these conditions8. The Health Protection Agency and Department of Health Guidance on managing CDI recommends that PPIs should only be used when there is a clear clinical indication16. The 6 guidance also states that consideration should be given to stopping PPIs in recurrent cases of CDI. Current evidence regarding interactions between clopidogrel and PPIs is not consistent; however, the MHRA has advised that the combination of clopidogrel and omeprazole or esomeprazole should be avoided unless considered essential17. 1.7 Good practice points to consider for this audit and during review of any PPI: Is there a legitimate indication for a PPI? Can the PPI be stopped? – e.g treatment course finished/NSAID discontinued therefore prophylaxis no longer necessary. Has the patient been tested and treated for H. pylori where appropriate? Could any medications that can cause dyspepsia be withdrawn? Have other strategies to optimise pain control been considered before using an NSAID that requires concurrent use of a PPI 8? Where a PPI needs to be continued can the dose be reduced? When stepping down or stopping therapy, has consideration been given to prescribing antacid/alginate for rebound acid hypersecretion? Have lifestyle measures been discussed and the patient advised on how to avoid precipitating factors? Has consideration been given to the risks associated with PPIs, particularly in patients with multiple risk factors for hospital-associated and community-acquired pneumonia, fractures or C.difficle infection8? The combination of clopidogrel and omeprazole or esomeprazole should be avoided unless considered essential. Where it is necessary to continue on treatment with a PPI, is the patient on the most cost-effective, appropriate PPI? practices could consider using specific read-codes for discussions with patients regarding stepping down or stopping PPIs and providing lifestyle advice 2. Useful Resources NICE Guidance - Dyspepsia: management of dyspepsia in adults in primary care10 WeMeReC Bulletin. Stopping medicines – proton pump inhibitor2 National Prescribing Centre. MeReC Briefing - The management of dyspepsia in primary care6 Map of medicine - www.mapofmedicine.com 3. Aim of the Audit/Review To estimate the percentage of patients who have an active repeat prescription for a HAC PPI on their record. To review all patients on a HAC PPI in line with NICE guidance. To ensure all repeat HAC PPI prescribing is appropriate. To reduce the use of HAC PPIs and increase the use of LAC PPIs relative to HAC PPIs 4. Audit Criteria All patients should have an indication for therapy when the PPI was initially prescribed. All patients on a repeat prescription for a PPI should have a documented indication for long term use. All patients prescribed a HAC PPI should have a documented reason for not being prescribed a cost-effective alternative. All patients should have a record of lifestyle advice recorded. 7 5. Review Criteria Patients with no indication for long term PPI should be stopped where appropriate. Patients requiring long term treatment with a PPI should be switched to a LAC PPI where appropriate. Patients on high and full doses of a PPI should have the dose reduced where appropriate. 6. Method 1. Find the total number of patients with an active repeat prescription for a PPI (A): Search the practice computer system for all patients with an active repeat prescription for a PPI (remember to search for branded products as well). Enter the figures for the total number of patients on the data summary sheet. Some computer systems will allow a search on the action group for PPIs to avoid having to enter the drugs individually. However, if you are not able to perform this search, the generic and branded names for PPIs are given below. PPI Generic Branded Esomeprazole Nexium® Pantoprazole Rabeprazole Protium® Pariet® Omeprazole Losec® Lansoprazole Zoton® (Tip- remember to include all formulations of PPIs including dispersible tablets and liquid specials) 2. Exclude patients prescribed a LAC PPI (B) Search the practice computer system for any patients currently receiving a repeat prescription for a LAC PPI (these are generic lansoprazole 15 and 30mg capsules, omeprazole 10 and 20mg capsules and pantoprazole 20mg and 40mg tablets). Enter the figures for the total number of patients on the data summary sheet. These patients should be excluded from this audit as they are the most cost-effective preparations. LAC PPI Omeprazole 10mg capsules Lansoprazole 15mg capsules Omeprazole 20mg capsules Lansoprazole 30mg capsules Pantoprazole 20mg tablets Pantoprazole 40mg tablets 3. Patients suitable to be included in the audit (C) Establish the total number of patients suitable for inclusion in the audit. This will involve removing patients on an LAC PPI (B) from the original list (A). 4. Sample (D): Select a number of patients on a HAC PPI to audit. Appendix A indicates a sample size which would give statistically significant results. The proportion of patients to sample may alternatively be decided at local level. Randomly select these patients from this list of patients to the required number. For practices where this number is less than 50, it would be expected that all patients be reviewed. 8 5. Complete patient data collection and carry out the patient reviews: A sample individual patient data collection/review form has been included and can be adapted for local use. Use the patients’ medical records to complete these forms and transfer the data to the collated patient data collection sheet. Review patients for their continuing need for a PPI, reduction in dose and suitability for switching to a cost-effective alternative. Any recommendations should then be actioned. 6. Find the post-audit/review percentage of LAC PPI After the audit/review is completed, and any necessary changes actioned, re-run searches (A) and (B) to find the new percentage. Notes: Indications for initiating a PPI Treatment of peptic ulcer disease (gastric and duodenal) Uninvestigated dyspepsia / reflux-like symptoms Investigated non-ulcer dyspepsia (NUD) GORD (endoscopy negative reflux disease and oesophagitis) Other As part of a H. pylori eradication regimen Prophylaxis of NSAID-induced dyspepsia/ulceration Zollinger-Ellison syndrome Barretts oesophagus Oesophageal stricture or ulcer Indications for long term use (PPI should be continued at current dose) Severe oesophagitis (Grades C and D) Prophylaxis of NSAID-induced dyspepsia/ulceration Zollinger-Ellison syndrome Barretts oesophagus Oesophageal stricture or ulcer Lifestyle advice10 – this should include: - healthy eating and avoidance of food/drink which exacerbate symptoms - avoiding reclining or lying down shortly after meals, and large, late meals - weight reduction (if overweight or obese) - smoking cessation - moderation of alcohol consumption Annual medication review - Medication Review Read Code and documentation regarding continuation of long term PPI in the patient record 7. Complete the Data Summary sheets 1 and 2. 8. Complete Practice Review sheet (see points below and data from the summary sheets to inform discussion.) 9. Return the Data Summary sheets 1–2 and the Practice Review sheet to your Medicines Management team on or before the 31st October 2011. 9 7. Results and Reflection When completing the Practice Review sheet consider: Are the results what we expected? Can we make any improvements? What might be stopping us getting better? Discuss the results of the audit within the practice. Details from the audit forms and summary may help identify further groups of patients to prioritise for review, or indicate patterns of prescribing on which to comment. Identify areas for improvement and formulate an action plan to optimise prescribing: Decide what it is that you want to achieve Think about how you will know if you are improving or not Generate ideas for the things that you could do differently Use some of the reference material to inform debate and discussion Record your progress. See section 1.7 (page 7) for notes and good practice points for reviewing PPIs. 10 8. References 1. North of England Dyspepsia Guideline Development Group. Dyspepsia: managing dyspepsia in adults in primary care. Full Clinical Guideline No. 17. 2004. Available at http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG17. Accessed Sept 2010. 2. WeMeReC Bulletin. Stopping medicines – proton pump inhibitors. Online content. October2010. Available at: http://www.wemerec.org/Documents/enotes/StoppingPPIsenotes.pdf. Accessed Nov 2010. 3. McColl KEL, Gillen D. Evidence that proton-pump inhibitor therapy induces the symptoms it is used to treat. Gastroenterology 2009; 137: 20-39. 4. Prescribing Services Unit, Health Solutions Wales. Comparative Analysis System for Prescribing Audit (CASPA) 2010. 5. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. NHS Better Care, Better Value Indicators. Available at http://www.productivity.nhs.uk/Indicator/626/For/National/And/25th/Percentile Accessed Jan 2011. 6. National Prescribing Centre. The management of dyspepsia in primary care. MeReC Briefing. 2006. Issue number 32. Available at http://www.npc.co.uk/ebt/merec/therap/dysp/resources/merec_briefing_no32.pdf. Accessed Sept 2010 7. Drug Tariff, January 2011. 8. Thompson A. Emerging Concerns with PPI therapy. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2010; 285:239-240. www.pjonline.com 9. Reimer C, Søndergaard B, Hilsted L et al. Proton–pump inhibitor therapy induces acid-related symptoms in healthy volunteers after withdrawal of therapy. Gastroenterology 2009; 137:80-87. 10. National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. Dyspepsia: management of dyspepsia in adults in primary care. Clinical Guideline 17. 2004. 11. British National Formulary. BNF 60. September 2010. 12. National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. Osteoarthritis. The care and management of osteoarthritis in adults. Clinical Guideline 59. 2008. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/CG59. Accessed Sept 2010. 13. Herzig SJ, Howell MD, Ngo LH et al. Acid-suppressive medication use and the risk for hospitalacquired pneumonia. JAMA 2009; 301:2120-2128. 14. Sarkar M Hennessy S, Yang YX. Proton-pump inhibitor use and risk for community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Intern Med 2008; 149:391-398. 15. U.S Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA Drug Safety Communication. Possible increased risk of fractures of the hip, wrist and spine with the use of proton pump inhibitors. May 2010. Available at http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders /ucm213206.htm. Accessed Sept 2010. 16. Health Protection/Department of Health. Clostridium difficile infection: how to deal with the problem. 2009. Available at http://www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1232006607827. Accessed Sept 2010. 17. Drug Safety Update April 2010, vol 3 issue 9: 4. Available at http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/pl-p/documents/publication/con076503.pdf. Accessed Sept 2010. 11 Sample Individual PPI Patient Collection Form Patient Name _________________________ D.O.B _______________ Patient ID______________ PPI Prescribed Omeprazole Lansoprazole Pantoprazole Rabeprazole Esomeprazole Dose/Frequency_____________ Formulation _________________ Length of treatment___________ Documented valid reason for HAC PPI - No Yes please specify ___________________________ Current PPI initiated in: primary care - secondary care - Indication on initiation Uninvestigated dyspepsia Uninvestigated reflux–like symptoms Endoscopy confirmed DU Endoscopy confirmed GU NSAID prophylaxis Not documented Investigated NUD Endoscopy confirmed GORD Other - Please specify ______________ Indication for long term use No Yes please specify ________________________________ PPI review within last 12 months yes - no - Lifestyle advice recorded yes - no - Reviewer recommendations/comments (include any relevant medical information to support recommendation and any local exclusion criteria) Recommendation: Continue unchanged Stopped Continue at reduced dose Switch to LAC PPI at equivalent dose State which________________________ Switch to LAC PPI at reduced dose State which________________________ Other _______________________________________________ Name ________________________ Signature __________________ Date __________________ Doctors recommendation/comments Agree with above recommendation Other __________________________________________ Doctor signature __________________ Date __________________ Action taken by: Pharmacist/Technician Practice Signature _______________________ Date ____________ 12 Collated Patient Data Sheet Patient ID/Number Daily dose Full Low High Intermittent/Symptom driven Yes/No Reason for HAC PPI documented? Uninvestigated dyspepsia Diagnosis/ indication recorded when PPI Initiated Uninvestigated reflux-like symptoms Investigated NUD Endoscopy confirmed peptic ulcer GORD (endoscopy confirmed) NSAID prophylaxis Other Not specified Yes/No Indication for long term use? Primary Care Initiation of HAC PPI Secondary Care Yes/No PPI review in last 12 months? Lifestyle advice recorded? Yes/No HAC PPI to continue unchanged PPI stopped Outcome Continue on HAC PPI at reduced dose PPI switched to LAC PPI at equivalent dose PPI switched to LAC PPI at reduced dose Other 13 Data Summary Sheet (1) Practice __________________________ Date of Audit _______________ Percentage of practice population Number Practice list size 100% (A) Number of patients in the practice with an active repeat prescription for a PPI (B) Number of patients prescribed a LAC* PPI (C) Number of patients suitable for this audit = (A) – (B ) *LAC PPIs are lansoprazole 15mg and 30mg capsules, omeprazole 10mg and 20mg capsules and pantoprazole 20mg and 40mg tablets only. Practice percentage pre-audit/review Percentage of LAC PPI to HAC PPI (B/A x 100) Number (D) Sample size i.e. number of patients from (C) included in the audit Number of patients with a documented indication for therapy when PPI initially prescribed Number of patients with a documented indication for long term use Number of patients who have had lifestyle advice documented in their notes with in the last 12 months Patient has had a review of their PPI in the last 12 months? % Suggested audit standard* 92% Percentage of the audit sample Suggested audit standard* 100% NA 90% 90% 90% 90% *these represent realistic standards based on clinicians’ discussions as objectives for the time of the audit cycle. 14 Data Summary Sheet (2) Factor Number of patients with this characteristic Total sampled Standard daily dose Low daily dose High daily dose Intermittent/symptom-driven regimen HAC PPI initiated in Primary Care HAC PPI initiated in Secondary Care Outcomes Number of patients with this characteristic Factor HAC PPI to continue unchanged PPI stopped Continue on HAC PPI at reduced dose PPI switched to LAC PPI at equivalent dose PPI switched to LAC PPI at reduced dose Other (E) Total number of patients on PPI post audit (F) Total number of patients on LAC post audit Practice percentage post audit/review Percentage of LAC PPI to HAC PPI (F/E x 100) % Suggested audit standard* 92% Please send the Data Summary sheets 1-2 and the Practice Review Sheet to your local Medicines Management Team who will compile the local information and forward to the Welsh Medicines Partnership for a national perspective. 15 Practice Review Sheet A. What lessons did the practice discover from carrying out this audit/review? B. What discussion/activities did the practice undertake as a result of the audit/review? C. What changes have the practice agreed to implement as a result of this audit/review? This audit was completed by: Name(s) __________________________________________________________________ Signature(s) ___________________________________________________________________ Practice (name and address) ______________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________ Please send the Data Summary sheets 1-2 and the Practice Review Sheet to your local Medicines Management Team who will compile the local information and forward to the Welsh Medicines Partnership for a national perspective. 16 Appendix A Sample selection Total number of patients on HAC PPI Sample size: 95% confidence; +/-5% 44 79 108 132 50 100 150 200 17