Two dominant ideas of home in the renaissance of home in today's

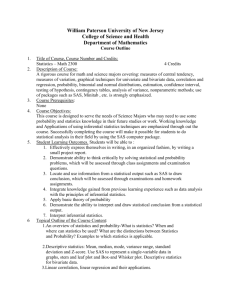

Mette Mechlenborg

Two dominant ideas of home in the renaissance of home in today’s culture

The dream of the good life is no longer out there. It’s at home. Home is cool.

It’s exotic, alluring and important. We see the tendency in the discussions on home, homeland, nationality and family in politics and in the endless numbers of interior – and decoration magazines, which have found their way to the newspaper stands all over the country. Home is also what the great Danish writer Klaus Rifbjerg wrote about, when the Danish publishing house

Gyldendal asked him to write a book about the most significant event or place for him in the last century ( The House , 1999). And the home has been the main theme in art exhibitions, film and literature, where it has been seen as a vantage point for experiences and human stories. We have seen the emergence of study groups, workshops, seminars and special issues about house and home, organised by universities and places of learning all over the country. From all these different perspectives, the home is perceived as a particularly complex and emotional juncture in our lives, which we on the one hand do all we can to get out of and set out from but which we again and again are drawn to. Conclusion: Home has become a very popular and strong slogan in the late modern age.

Thesis

After having studied home as a cultural phenomenon since 2001, it appears to me that two ideas dominate the field. One is The Return of the bourgeois

Home (the nuclear family, the house and the tradition), the other is

Domestication (which is not related to the house but to the strategy used to create a sense of home in traditional non-places). These perceptions are on one hand opposed to each other but on the other hand they reflect the same problem.

My assumption is that the current idolisation of the home is really about two things: it is an aestheticisation of the concept of home - and a rejection of a culture, which throughout the last century has favoured mobility over stagnation, change over rootedness and last but not least, cosmopolites over locals (Bauman, Morley, Papastergiadis, Tomlinson etc.). In other words: the current obsession with home reintroduces the home as the fulcrum for the late modern understanding of self. Which has consequences not only for our understanding of the idea of home, but also affects the identity and sense of self of the ordinary person.

All this to imply that the renaissance of home can be seen as a chance to renew the focus on the relation between ideal home and actual home in contemporary housing research. The choice of home is a complicated process,

which often brings out very individual solutions that can be difficult to make sense of. Differences aside, most researches agree that even the most personal solution should be seen in the light of prevailing theories on modernity, globalisation, social mechanisms etc. The question is whether the same could also be said for that particular cultural aspect which will be the fulcrum of this paper, namely commercial culture – tv-commercials, advertisements and slogans which form the empirical basis of my study.

Hopefully an analysis of the idea of home as it appears in certain advertisements will shed some light on the emotional motivation, which lies behind the choice of a permanent home.

Cultural phenomenological starting point

My method is cultural phenomenological. Theoretically I am close to the understanding of the idea expressed by Professor Stephen Connor in his book

Cultural Phenomenology (2000). To Connor, cultural phenomenology is a way of understanding culture as well as a working method. One of the key words is the way we understand experience. In an explicit rejection of constructivism,

Connor defines culture as an inter-subjective consciousness. Culture is neither pure experience nor absolute explanatry models. Culture is

”experience becoming explanation, experiencing experienced as a way of explaining”

(2000:4). This ambiguity between experiencing something and making the experience accessible in a meaningful way, means that culture must be seen as a dynamic genesis. Within culture, meaning is constantly in flux between experience, processes and objects. As he puts it quite simply ”To say something is cultural is to say simulaneuosly that it is shared and that it is made” (2000:3).

The cultural phenomenological method is therefore not driven by a search for the meaning of things but ”what are things like?” (2000:3). This approach means that rather than a employing a traditional detached perspective, Connor encourages us to ”getting amidst a giving subject” in order to “heed the affective, somatic dimensions of cultural experience” (2000:3)”. This type of inthe-world method can only be acheived if the area is approached with an open mind and communicated “more excitable, inflammatory, absorbed and perplexed” (2000:5).

This is where Connor’s Cultural Phenemonology is most interesting but also where it is weakest. It is hard to see how an analysis that is purely cultural phenomenological, in its poetic and self-engrossed approach, can be performed without becoming a cultural object in itself. Connor comments on this problem when noting that the surrealists can be seen as the forefathers of his theory. It is first and foremost as critical theory that Cultural

Phenomenology gains its strength. First of all, because it creates an understanding of culture as a dynamic space to experiment with values and ideas, secondly because it can make us reevaluate certain conventions and preconceived ideas, that we often approach things with.

In the following I am going to use Cultural Phenomenology to look at cultural ideas of home with unconventional eyes, to work out ‘what things are like’.

More specifically my point of departure will be that part of commercial culture, which is ‘made’ and ‘shared’ to a great extent, namely advertisements.

Advertisements have always tapped into the dream of the good life. With the built-in element which is the nature of dreams, that it is exotic and reserved for the fortunate few. On the other hand, the advertisement would never be able to appeal to its audience if it didn’t contain a bare minimum of reality. It needs to contain some sort of recognisability and identification in order to work. These elements make advertisements a unique example of C onnor’s definition of culture: The ad partly shapes our dreams and our idea of the good life (made).

At the same time, the ideas that the advertisements represent are ideas, which already exist within culture (shared). A good advertisement captures the new and expresses it. In that respect the advertisement, as genre is a privileged approach to those experiences and explanations that are being developed within contemporary culture. Also when it comes to house and home.

Two typical cases

In practice my cultural-phenomenological analysis will be ideal-typical examples rather than an attempt to cover the large number of conflicting views.

My analysis of the two dominant ideas of home will be illustrated in two ideal type cases. Both cases are TV-ads that have been shown on national TV for a whole year running. The home is a central theme in both cases and they both represent a new way of understanding home compared to more traditional notions.

The first ad is from a campaign launched in 2004 by BG Bank, a large Danish bank, which was set off with the slogan “What would it cost to feel at home?/

Little differences count”.

The campaign was shown in most of the ad-carrying TV channels and the target group was young middle-class families about to become homeowners.

The ad I’ll be referring to is called The Trophy and is a textbook example of

The Return of the bourgeois Home in commercial culture, in the sense that it contains many of the problems connected to this idea.

The second case is an ad by the international company SAS Scandinavian

Airlines, which like BG Bank is known for its large-scale campaign focusing on the home. The campaigned entitled It’s almost like home was part of another, larger campaign created by the international advertising company Leo Burnett.

The TV ad that I am referring to is known as ‘The Light’. Contrary to the BG

Bank ad, this one has an international scope and doesn’t appeal to the younger generation who are about to settle down but rather to the cosmopolite, the travelling businessman or woman who often spends time in airports and would be a potential buyer of an SAS business card. When I’ve picked this ad to represent the other dominating idea of home today, it is because of its very clear communication of a an otherwise complex phenomen, Domestication.

The Return of the bourgeois Home is at the core of the current idolisation of the home. Primarily because it contains a built-in reflexive element, in the sense that this is a return of something that (apparently) has been absent but has now come back. By placing the bourgeois home as a reflection of how the

good life ought to be lived, not only do we rewrite the history of home, we also redefine the qualities we associate it with: the nuclear family, private life, marriage, children, tradition, the house, property rights, the chores etc.

Domestication is on the other hand a clear sign of what is at stake in the current idolisation of the home, in that it exemplifies the aestheticisation of home to such an extent that you could in fact talk about an expansion of the traditional concept of home.

Idea 1: The Return of the bourgeois Home

BG Bank: What would it cost to feel at home?/ Little differences count : “The

Trophy”.

It’s a spring day. The sun is shining, birds are singing and a young couple in their early thirties are moving into a villa. There is no dialogue between the characters, everything takes place as non-verbal communication and the ad actually uses very few devices to tell the story. In a dramatic way the ad is spun around the important decisions made when a couple move into their first permanent home: What is going to be thrown out and what will take part in shaping a common future? What belongs in the past and life lived so far? What will be part of the family life that replaces it? The central question is what does it cost to feel at home. This question is what shows up on the screen at first before the action starts.

We start off inside the villa, which is being decorated by the couple. He is painting the walls with his back to the camera. She appears in the door opening with some sort of hunt trophy, known from the 1950s home where it would have hung above the sofa. She glances at her boyfriend to see if he has noticed what she is up to, before she carries on through the door and into the garden. The trophy is apparently heavy and she eventually gives up carrying it and instead drags it across the grass over to a scrapheap. She places it next to an abandoned vacuum cleaner, a broken chair, a dust bin and other rejected things that for some reason or other have not been considered worthy of becoming part of the new home, the couple is creating. Triumphantly she turns round and walks back to the house.

In the next scene the man is in the doorway looking out. He turns his gaze to the scrapheap and with an affirmative look in his eyes, moves in the same direction. When he reaches the heap he crouches in front of the trophy, weighs up the situation while holding the animal gently in his hands.

In the next scene he holds the trophy in his arms and is walking back to the house with it. The face of the trophy is turned towards him and he occasionally looks down and smiles. Once he is inside the house again, the voice-over says: “It’s one thing to buy a house. Another thing is to create a home”.

Whereupon the slogan – and the moral of the story – appears on screen: BG

Bank. Little differences count.”

Home is good

BG Bank appeals to young couples and young families who are considering buying a home. You might wonder why BG Bank does not do more to flag up the advantages of being one of their customers. Where is the ad about the favourable loan opportunities, low interest rates or good housing policies, which might tempt the target group? The absence of financial reasons in the

BG Bank ad has been replaced by less rational aspects of becoming a homeowner. In their own words: “It’s one thing to buy a house. Another thing to create a home.” If the ad is right, the homemaking is not only situated in the house itself, but in the emotional superstructure that has become symbolic of the home: The family, love and the we-feeling.

The discovery - or rediscovery - of the home as a emotional symbol is interesting not so much for the fact of it, as for the valorisation of it. Home is positive. Home is good. Off course this has always been the case to the majority of the population, who has never stopped celebrating the home as the prime scene of family activities, traditions and consume. What is interesting about this renaissance of home is that the popularity of it also echoes at the level of high culture and ideology (Kumar, Morley). Until recently home has been a symbol of an anti-modern state of mind (Reed). But now it seems that home and domesticity is returning to a position of cultural prominence. Which is exemplified in this ad, where BG bank tempts the viewer with the feeling of home rather than the more prosaic aspects of buying a property. If the home previously was the natural backdrop in commercial culture, it is now at the centre of it, and has become a sales reason in itself. Homes sell. Why?

Home – a modern construct

Most researchers agree that home in the way we know it today is a social construct, which is inextricably linked to the bourgeois revolution and ideals on private property, free trade and individualism. The German philosopher and writer Walter Benjamin is said to be the first who pointed out the connection between home and modern society. In the article “Louis-Phillip, oder das

Interieur”, it is noted than it was in the early 1800’s that ”The living space became distinguished from the place of work”. The inventor, says Benjamin, was the “the private citizen” who because of his task of great responsibility in the creation of the free, capitalist and democratic soci ety needed an ‘interior’ where he could forget social as well as financial problems, and be himself. A room which purpose was not only to make the citizen feel ” far off in distance and time”, he continues, but which also represented ”a world [..] which was also better” (ditto). When the home to this day is explained in terms such as privacy, comfort and withdrawal – and over the years the nuclear family , these terms are part and parcel of the modern understanding of self. This sense of self separated outside from inside, work from non-work, rationality from emotion, concentration from recreation and atomised the large medieval household to a small nucleus consisting of father, mother and their own children.

Like all other constructs the bourgeois home is changing. Most researchers agree that the bourgeois home is a fragile construct which has never been

more threatened by individualismen, changes in family patterns and constantly increasing globalisation than the times we are living in. Globalisation alone has made it difficult to tie experience to one place and detached cultures from their original roots. An increasing number of people leave their home and their family and set out never to return. They settle in temporary homes before packing their suitcase again and moving on. And if we are not moving physically we are doing so mentally: We are able to surf the internet, switch channels on TV and gather information from anywhere in the world. We can communicate with people from anywhere, have intimate relations in cyberspace and chat with people we have never seen, we can become part of communities despite geographical, cultural and linguistic differences. If the home used to be the place one withdrew to when the world became to overwhelming and big, then the home of today is the gateway to the world with the internet, global TV-networks and mobile phones. Which makes it difficult to maintain the idea of home as ‘a small world, detached from time and space’.

The nuclear family isn’t doing to well either: According to the Danish Bureau of

Statistics, 35% of the Danish population live on their own – that’s about one million homes, the highest number we have seen yet. 40% of Danish marriages end in divorce and 25% of children between 0 and 18 are from broken homes. The sociologist Krishan Kumar echoes a wide range of researchers when noting in the article ”Home: The premise and Predicament of

Private Life at the end of twentieth century” (1994) that if it doesn’t indicate the breakdown of the home, then ”the fragments of the nuclear family” certainly involves

”the fragments of the home” (1994:228). According to Kumar the nuclear family should not be seen as a natural model for how intimate relationships are to be conducted, but as a transitional figure between the large medieval households and sheer individualism.

The bourgeois home is occupying culture with renewed strength, apparently with complete disregard for reality. One might wonder whether there is a certain nostalgia behind the return of the bourgeois home coupled with a desire for things to be what they were in the good old days. Or whether the idolisation really is a game of irony that plays with a construct, which is losing its authority. If we look at the example of the BG Bank-ad, the answer would be yes in both cases. The return of the bourgeois home is therefore both nostalgic and ironic.

The return as nostalgia

The surge of interest in the bourgeois home seems paradoxically to be linked with the fact that it has become an exotic and almost unattainable ideal. The house featured in the BG Bank ad is, unsurprisingly, the dream home to the majority of the Danish population. A study conducted by City Forum (Boforum) in 2001 showed that 90 percent of young families (< 35 years) hoped to own their own home within five years and that a detached house in the shape of one-family houses, country houses or master built houses, is the ideal to 90% of them. Strangely enough, the study also shows that the number of properties sold to the group of people intervewed has fallen dramatically since 1989, which indicates that the gap between the ideal home and the home they are

actually living in, has increased drastically.

The same goes for the nuclear family which seems to have recaptured its position as ideal after having suffered for years under the demonstrative experiments with family structure carried out by the 60s generation. TV realityshows, which have families as their starting point, are on the increase, this also goes for the so-called Nanny-programmes, which help busy and clueless parents become good parents. Add to this the recently created Ministry for

Families, the flood of parent-magazines, trendy toys, clothes, accessories and merchandise for kids or rather, for the fashion-conscious parent. The message in an ad campaign for the perfume Eternity from the lifestyle company Calvin

Klein, which currently is in all national men’s and women’s magazines, is crystal clear. Rather unusual for a company that has earlier been known for applauding the freedom of the individual: In this ad the famous model Christy

Turlington is shown in the midst of the quintessential happy family: In bed with a father and a beautiful little daughter, playing with a rabbit. I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s Sunday and dad will be fetching breakfast soon! For those who might be a little slow, the ad rubs it in by quoting a line from Burt Bacharach’s saccharine sweet ballad: “What the world needs now, is love, sweet love”.

While divorce rates are going up, the family has become a status symbol along with the perfect body and the perfect home.

The idealisation of the bourgeois home, which is what is going on here, centers on the trophy in the BG Bank ad. It is this what triggers the action. As a symbol of an ideal past, the hunt trophy is one of the most significant accessories of the 1950s home. From a time long gone, it reminds us of back when the housewife was the pillar of the home always smelled like freshly baked bread and the family always went on Sunday outings. Or rather – it reminds us of a time before globalisation could be felt in the homes, before mum and dad got divorced and the centre of the world was where you lived. In other words, a time when the bourgeois home was at its strongest.

The nostalgia of the hunt trophy, as in the master built villa and the nuclear family, is pretty obvious. But the question remains whether the yearning for the past is actually grounded in a realistic historical image. Because when we think of the bourgeois home, it seems not so much to be the social-realistic home we are interested in, as it is a symbolic construct of what seems to have been lost in the late modern focus on individualism, capitalism and globalisation. Namely rootedness, community, stability and a pre-ordained meaning of life – in other words, elements we connect with home.

This type of nostalgia connected to the home is what Nikos Papastergiadis insists in his work Dialogues in the Diasporas (1998). He argues that the concept of modernity, particularly in relation to globalisation is imbued with the idea of a lost home and with a feeling of stress over a permanent homelessness that this experience of loss has evoked. The reason is, he says, that the concept is stuck in a far too unambiguous perception of tradition versus modernity, rootedness versus change. In this (often) stereotypical universe home is seen as a privileged place of comfort ”locked into the frozen

time of the past: bound to unchangeable customs; restricted to pure members; ruled by strict father figures; sti fles by religious beliefs” (Papastergiadis

1998:7).

The almost demonstrative idolisation of the bourgeois home in advertisements,

TV-series and magazines is perhaps the best example of the fact that the bourgeois home no longer has a natural authority i n late modern man’s way of living. Compared to other contemporary reintroductions of home, these proponents of ‘the real home’ have assumed an almost desperate position, which in many cases seem to be attempts to curtail a development that already has taken place. But often these perceptions have little to do with reality. They are rather an exploration of the characteristics of the traditional home with a view to creating new, more up-to-date constructs.

So it is not so much the bourgeois home as a role model for how things should be, which constitute the homemaking in the BG Bank ad. The point being that it is the small differences that count. In this case a hunt trophy, which supposedly will decide whether the sense of home will occur in the new house

– at least for the male hero in the ad. This is the irony of it.

The return as irony

The challenge is to see the idolisation of the bourgeois home as a game that plays with historical elements out of context, not necessarily bound up with a particular moral codex, a way of living or a time and therefore does not represent a demand or a model for how things should be. The same goes for the BG Bank ad. The bourgeois home, as a particularly privileged place of belonging and at-homeness, is explored and idealized, through a detail or prop that becomes a metaphor.

Nothing in the ad indicates that the young couple plan to establish themselves as one did in the good old days. They are a modern couple. She helps out with the practical work. He does household chores. At the same time her determined manner indicates that she in no way has succumbed to a possible patriarchal superiority and outdated gender patterns. The hunt trophy shows that the homemaking that is taking place does not originate in a collective “we” but is rather a coverup for a negotiation where the individual’s needs and desires are put forward and then coordinated accordingly with the opposite party. She throws out his things without asking. He goes against her wishes without confronting her with it. If Kumar is right in his assumption that individualism is one of the greatest threats to the community that is the foundation of the home, then this family seems to have rendered the process of creating a home impossible before it has even started.

Perhaps the nuclear family we saw in the BG bank ad is an example of one of those modern relationships that Anthony Giddens defines as ‘the pure relationship’. The pure relationship is, in his own words, a relationship “in which external criteria have become dissolved: the relationships exists solely for whatever rewards that relationship as such can deliver”. (Giddens 1991:6). The radical serial monogamy that is a consequence of it has been purged of any

kind of cultural convention and limitation. The involved parties reach an agreement on the contents of the relationship, which can be dissolved at any time, should one of them find the relationship unfulfilling in one way or another.

The pure relationship is, according to Giddens, the only relationship, which can work in a culture dominated by utter individualism. But the advertisement doesn’t go that far in its self-critique, only because the ad does not allow any invitation to negative interpretation by letting the core of the conflict be an ironic piece of cultural history. The symbol of the desired athomeness is paradoxically enough, and also the element that threatens to deconstruct the entire home. This is perfectly illustrated in the final scene, which can be read as a covert ironic comment on the film rescue scene. After a long and painful separation, he is finally reunited with his beloved. He takes her gently in his arms and carries her to safety. She looks admiringly at him, the two of them merge and the credits start rolling. A man and his elle.

This doubleness in the approach to the bourgeois home is something we find across the board in contemporary culture. This is also why we cannot just reject the idolisation as pure nostalgia or irony, but must view it as a positive valorisation of rootedness and stability in a time where change, individualism and mobility have become fundamental conditions. It’s not coincidence that traditional household chores such as knitting, crocheting and embroidery have become trendy again. The trend can be measured directly in the number of wool and textile shops that shot up over the past 3-5 years – and in the city cafés young, fashion-conscious women sit in their home-made clothes with their knitting and give off a sense of surplus energy, time and housewife virtues. The return of the bourgeois home also seems to have influenced

Danish food culture. Old-fashioned Danish cuisine is seeing a renaissance and several highprofile cafés and restaurants which target the well-off young generation have now got parsley sauce, fried pork and beetroot on the menu, along with other classic 1950s dishes. Exotic food is no longer coming out of

France or Asia, but from our own historic back garden! Once one has noticed this tendency, it becomes apparent that many similar examples idealise the home as a kind of fashion.

It is perhaps this exposed feature that is the most characteristic of the return of the bourgeois home after decades that rejected everything that was bourgeois.

The bourgeois home now seems to be a treasure chest of forgotten exotic objects, like a hunt trophy, which is taken out and incorporated in the staging of one’s values and priorities in life. Home is hip. It is exotic, alluring and new.

Whether the argument is nostalgia or irony, the idolisation of the home is first and foremost something that takes place in the public space. The at-homeness feeling is exposed, idolised and discussed, not only as public affairs but also as detached elements in an individual’s lifestyle project. The aesthetication of the home, which is a natural consequence of this, influences not only the role the home plays in society today – it also influences ordinary people’s sense of self, in that it is seen as a symbol of values and priorities.

Intermezzo

The return of the bourgeois home is the object of much discussion in our culture – it is nevertheless in competition with another prevailing idea of home, namely domestication, although domestication does not deal with the home in a traditional sense (the house, the family, the tradition), it also experiments with the at homeneness feeling aesthetically. Let’s take a closer look at the SAScampaign ‘It’s almost like home’.

Idea 2: Domestication

SAS: “It’s almost like home” /“The Light” (Leo Barnett, Norway 2004): A young man with a well-trimmed beard, relaxed attitude and trendy black glasses, walks into a kitchen, reading a newspaper. He casually flings his jacket over the back of a chair in what appears to be a kitchen, but on close inspection turns out to be an airport lounge. Still focused on his reading, he moves around, apparently familiar with the setting, pours himself a cup of coffee and sits down with his paper.

In the next couple of scenes, we are shown various close-ups of the man. In one shot he concentrates on his reading. In the next, he is leaning back with his hands behind his head and tilting his chair back. Time passes. He finally glances at his watch, gets up and collects his things. He smiles to himself, not noticing the woman by the kitchen table, the people around him or the loud speaker announcing departures and arrivals. Lost in thought, he leaves the room and turns off the light switch in the way you would if you were at home. A few objections are heard and it is only then that he realises that he is not alone. He leans against the wall with the switch on one side of him, shakes his head and switches the light back on. Immediately afterwards the background music grows stronger and as he leaves us, the slogan appears on the screen:

“It’s almost like home. It’s Scandinavian – SAS.”

2.1 Expansion of the idea of home

As in the BG Bank as the at-home feeling is the main message here. In the slogan “it’s almost like home” as well as with the images SAS taps into the nostalgia the traveller often is hit by – the yearnning for home once you have left it. At the same time the ad belongs to a certain terminology, which, from the beginning of modernity has opposed the journey to the home, the new to the familiar, the modern to the traditional.

The airport has always been one of the globalisation theoretician’s favorite symbols, as airports connect cultures, language and countries, and revokes the classic time/space aspect. The airport is the centre of movement, coincidences, and the coordination of complicated affairs and activities. The airport is everywhere and nowhere, in the airport you are in a transnational environment and you are the cosmopolite. When SAS compares their airportlounge with a home, it not only changes the set of values that airports represent, it also expands our understanding of home. How can one feel at home in an airport without revoking the concept of the airport (as a non-place, movement and anonymity), and how can one take one’s home to an airport without losing the meaning of home (the particularity, stagnation and

familiarity)? In order to do this we need to expand the concept of home and to regard the feeling of being at home as a singular home-trait, which can be invested in new shapes, varieties and places.

2.2. Heller: At-homeness as detachment

This is exactly what the philosopher Agnes Heller does in “Where are we at home?” (1995). Her main point is that the ability to feel ‘at home’ is tied up with the particular frame of experience you belong to, and this ‘colours ‘ the way in which you see the world. While the bourgeois home in a traditional sense is connected to a frame of experience, which is grounded in space (the house, the city of birth, the home country), a new frame of experience grounded in time is beginning to dominate, she claims. Heller explains the difference between the two by describing two apparently actual people she has met. One is the owner of a little trattoria by Campo dei Fiori in Rome, who reveals to her when she asks him for directions, that he has never been outside his local area and therefore knows nothing outside the world his geographical home has created a natural boundary around. The other is a businesswoman Heller meets on a plane. The woman speaks several languages, owns homes several places in the world and when Heller asks her where she feels at home, she answers sarcastically: “where my cat lives”. Heller argues that the trattoriaowner sees the world as a type of geographical monogamy”. A loyalty towards the one place, that connects him to tradition and local life but which also gives him a strong sense of belonging, which can be seen, rooted in ”language, the mother tongue, the local lingo [..] the gestures, the signs, the facial expresseions the minute customs” typical of his region and which make him famil iar with ”sounds, the colours, the lights, smells, the scapes” of his local area(1995:56). In his eyes the businesswoman seems ‘geographically promiscuous’. Through her numerous journeys she de-terrritorialises places, she is indifferent to her whereabouts and apparently undermines the concept of home by equalling it to where her cat is. But, as Heller argues, this woman does not belong to the type of culture that is grounded in space. Her view of the world is based on time. The career woman moves around in the world, but that doesn’t mean that she doesn’t also experience a sense of stability, security and belonging. The familiar is tied to the fact that she doesn not perceive the world as a geographical, but rather a temporal space. To her, travelling from one place to another seems ”as if all those remote and less remote places moved towards her and not she towards them” (1995:3).

Precisely as the trattoriaowner feels that he is at the centre of the world, namely Campo dei Fiori, the business woman is always in the centre of all the different timezones she is moving in, a kind of absolute present: ”What she carried on her back was not a particular culture of a particular place (or places) but a particular time shared by all the places.” (1995:3). So in that sense the businesswoman also has a sense of home. Her world, rooted in time, is equally saturated with the repetition of rituals and habits of homemaking and it is just as marked by the calm that occurs, when you know what tomorrow will bring.

The busin esswoman ”stays in the same Hilton hotel, eats the same tuna sandwich for lunch. [..] She uses the same type of fax, and telephones, and computers, watches the same kind of films, and discusses the same problems

with the same kind of people.” (1995:2). She sleeps in the same side of the bed, she knows where the light-switch is in most hotel-rooms and which problems might occur when ordering food in any given restaurant anywhere in the world, just as she knows how to solve those problems. In her world of international businesses she is able to read the facial expressions and the allusions of the people she meets in offices, restaurants and at meetings and she understands them ”without explanations” (1995:4).

This rather abstract sense of home makes the businesswoman something of a paradox. She is on the one hand homeless, in the sense that she has no fixed place, which her familiarity with things and with spaces centres around and from which all activity takes place. On the other hand, she still has a sense of home and belonging. She is so much a part of international culture that she is intimate with many things that characterise this culture, which Heller very much to the point describes as ”cosmopolitan of things we use” (Heller 1995:6).

It is precisely this distinction between home (geographical) and feeling at home

(mobile) that is one of the two preconditions for the SAS ad and for

Domestication as phenomenon. The point of “It’s almost like home” is exactly that the protagonist is not at home, yet feels at home because he is familiar with the space and the things in it, and is able to hold his own here, as he would have been able to at home.

The cup of coffee is in more or less the same place as it is at home. The same goes for the kitchen table. He has the same sense of atmosphere and calm as he recognises from his own intimate sphere. Precisely like heller’s businesswoman. But one important difference must be mentioned. Because where the businesswoman has created this sense of being at home through a laboriously built up structure of habits and by returning to the same places again and again, doing the same things and creating a certain familiarity, the feeling of home in the SAS ad is not taken from the repetitive patterns and recognisable rhythms of travel, but from the home.

Aesthetic Strategy

The concept of domestication is a constructed word and in my terminology it refers to what happens when a non-place, like the airport, becomes a place where a sort of home-making takes place. The Danish cultural sociologist Ida

Wentzel Winther has reflected on this in her PhD ‘Home and Homeness’. To make something your home is an action, she argues. An activity that needs a verb, “to do”. Winther introduces the term ‘to home it’. Winther’s verb is close to my concept of ‘domestication’, as domestication assumes that someone has domesticated something.

To explain what ‘to home it’ is, Winther draws on the sociologist Mary Douglas’ article ‘The idea of home: a kind of space’ (1991), which sees home as space und er control. The purpose of ‘homing it’ is to make the person who is ‘homing it’ feel at home. It is a kind of tactic that has a particular emotional purpose.

The verb ‘to home it’ is the tactic that will create a feeling of home. In a banal sense, we are ‘homing it’ when we arrive at a new hotel room, take our clothes

out of the suitcase, put the shoes in front of the bed and leave the toothbrush in the bathroom. The point of homing it, Winther claims, is that it is a willed act.

You cannot have the feeling of home forced upon you. ‘To home it’ comes directly from the subject. She says: ‘You cannot ‘home it’ mechanically against your will. You can be in one place, physically, you can practice strategies, but their needs to be a will to make it happen. This m eans ‘homing’ tactics cannot be instrumentalised or commercialised – and then she carries on in a footnote:

‘in which case it would involve strategies’ – referring to Michel de Certeau’s distinction between strategy and tactic. Winther does not get to the bottom of

‘homing it’ as strategy, but simply concludes that certain commercial activities play around with “the relationship between tactic and strategy”, which results in this no longer being individual tactics, but that “homing it becomes enforced”.

Nev ertheless, it is the ‘homing it’ as strategy, which is interesting in relation to domestication in genera l. In the SAS case there is no subject ‘homing it’ in the sense of an individual act of will. No one in the ad uses the tactile, where a room is over-t erritorialised by making it recognisable, safe or by creating one’s own feeling of home, as we saw it with Heller’s businesswoman. Noone in the ad leaves a trace and no one forces his or her will on someone else. When the protagonist acts as if he is at home in the ad, it is because he confuses the lounge with his home. This is the main point of the ad.

SAS have purposely decorated their lounges to make them look like a room inside a home, a kitchen. They have placed kitchentable, cupboards and chairs as they typically would be placed in a Scandinavian home and they have furnished it in a cosy style, recognisable from many houses. At the same time they have removed the traditional loungebar in favour of a home-like selfservice, allowing visitors to make their own coffee or tea, without having to drag out your Mastercard and in that way be reminded that you are not at home. SAS are trying to be what many travellers often need or miss when they are on a journey: A place that opens its arms to them and welcomes them. A place that does not demand that they make decisions or behave in a certain way, a place where they can relax and be themselves for a short moment. But without turning it into the anonymous private room in a hotel. The SAS lounge is organised in a way that appeals to a particular social interaction, which is different from the way hotels appeal to you – the SAS lounge appeals to the way you behave when you are at home. At home you are yourself, but you are never anonymous as in the hotel. In the home, ideally, you are part of a family.

It is this emotional appeal, created by an aestetic staging which is the fulcrum of the strategy and which makes it feel like home although it isn’t. The staging is not only physical but also utterly rhetorical. The s logan “It’s almost like home” draws on pathos and nostalgia and at the same time reveals to the customer or viewer, what the purpose of the layout of the room was. The next time you see this layout, you’ll know that you can expect a feeling of home.

The cognitive element plays a central part in the domestication. It opens our eyes to the fact that we can feel at home other places than in our own homes

(in an SAS-lounge for example) and it is precisely this positive expectation towards alternative home-rooms, that is the purpose of the SAS ad.

Contrary to Winther I do not believe that ‘homing it’ is a negative strategy, while

‘homing it’ as a tactic is positive. First of all because I do not believe that it is strategically possible to force people to ‘home it’. Secondly, I am convinced that this is not about controlling people. Of course it will take some planning before domestication will result in a feeling of being at home to the individual.

But it is not, as Winther believes, an activation of the act of ‘homing it’ which is put into play, but an activation of what the gesture is intended to produce, namely the possibility of feeling at home. As SAS implies in the ad, the work has already been carried out. Someone (SAS) has already be en ‘homing it’ for you, or in other words: The room has been staged with familiar elements in order for you to feel more at home, without actively having to ‘home it’.

Another important point to be aware of, is that this is not just any old room,

SAS has chosen to domesticate but a room where the individual already has been ‘homing it’. A place where travellers, like Heller’s businesswomen and

SAS’ young man, often hang out for a bit, take off their jackets, read their newspapers, call their partners and for a short moment are allowed to be themselves. The domestication in the ad takes place in a room that already has been domesticated by other travellers. All SAS does is to visualise it: The individual ‘acts of home’ are underlined by the layout and design of the room, where they become accessible to all.

In this perspective the SAS ad is only a commercial and cultural example of the tendency within urban planning which focuses on human needs within public space. The Danish architect Jan Gehl has discussed this tendency - Gehl has argued for years that exterior spaces should be improved so that they appealed to human activity and social gatherings rather than anonymity and detachment. An example of this is the renovation of the harbour at Islands

Brygge, where as well as playground and pool, a number of out-door kitchens and dining tables were put out as a frame for individual, domestic activities in a public space. This way the traditional division between outside and inside, private and public, home and non-home was graduated.

Based on the discussion we have just seen, we can conclude the following:

First of all Domestication is a strategy which is used by powerful agents (airline companies, urban planners and architects) to domesticate a room; in other words welcoming, appealing and open to domestic activity. Domestication occurs by moving certain elements (props, sizes, habits, activities, aestetic and rhetoric) which otherwise belong to the home in a non-domesticated room. This results in a sense of someone ‘homing it’ for you as a strategi. Secondly the rooms that are domesticated already have the potential to be domesticated.

Either because people already have been in the habit of ‘homing it’ in this room, or because these rooms are the ideal places to do it in. From a philosophical point of view, domestication also means that the historical gap is bridged as well as, according to Papastergiadis, stereotypical perceptions of home and travel, stability and mobility, tradition and modernity, in this case symbolised by the airport and the private kitchen. Domestication is to create an oasis in the in-between space where people can stop and breath, get an overview of things without getting lost in the restless nostalgia of travel and

without succumbing to the claustrophic stagnation of the home.

Conclusion: Two recognitions

The sense of belonging is under threat in the late modern and this is why it is endlessly idolised. Globalisation, individualism, new family patterns and work habits have changed the bourgeois home without us realising it, until now. At the same time elements such as stability, emotions, community, history and rootedness are in short supply in a cultur where we ARE individualists in motion in a globalised world where the conditions are ‘the pure relationship’ as described by Giddens (see “The return as irony”). In response to this a new form of sensibility in relation to the home has emerged and appears as a nostalgic idealisation of old-time classics such as knitting, the nuclear family, the house, old-fashioned Danish cuisine and traditional housekeeping. But we have also seen experiments rooted in new forms and varities.

The idolisation of the home is cultural and real at the same time. It is about the actual home

– the house, the family, the homemaking and the private room.

But it is also about home as a modern space for discussing values and identity, as well as a rejection of a culture that up till now has privileged the global over the local, new over tradition, changes over rootedness. Not that there is no connection between the real and the cultural home, on the contrary. They should be understood as dynamic poles between made and shared, where experiments with new concepts and ideas are carried out. Two aspects are worth mentioning in relation to the current research being carried out on housing.

Home as identity

As we saw in the BG Bank adm the Return of the bourgeois home means using a social construct (the home) in an aestetic way (as symbol, the hunt trophy in the BG Bank ad). On the other hand, Domestication is defined as creating a social room (similar to the home, the SAS ad, the kitchen) by using aestetics (design, rhetoric). In both cases reflection and staging play an important part: Reflection, the staging presupposes that the characteristics and the expresssions are carefully thought through in the staged elements. Staging because the part that is being reflected upon will always have to be drawn to the front. This corresponds with the general aestheticisation of life that

Giddens among others is an exponent of in Modernity and self-identity (1991)

If you draw the consequences of his theory, the home must also go through the same process: Rather than a place we simply live in, the home is a place we tell stories about and that we stage in relation to our constantly revised biographies. Telling your home story means saying who you are. Where are you from? Where do you belong? Where are you emotionally involved? Thus the question of home is inevitably a question of identity and the constitution of a meaningful life project.

Giddens calls this project for ‘the reflexive project of the self’, understood as the constant revision of own identity compared to new value, ideals and situations. If we accept this connection between home and identity, it suddenly makes sense why DIY-programmes in TV have seen a massive increase in

recent years and why more and more money is being spent at home – decorating, building extensions and refurnishing. But it also explains why children are seen more and more in public spaces, why weddings become more and more spectacular and why awareness of one’s roots (family tree, childhood home, place of birth, home country) has become so important. They are all central components in ‘the reflexive project of the self’.

This recognition is worth noting when studying the relation between the cultural home and the homes we inhabit. The idea of the perfect home should not necessarily be related to a particular house, which building owners should respect. It could just as well be understood as a symbol of those particular questions, values and characteristics that concern us today.

Between rootedness and change

Another important aspect in the current renaissance of home which concerns the study of housing, is what this idolisation does to the actual home and to the demands that modern people have of their house and home. Is the bourgeois home, in shape of the classic house with garden, nuclear family and community feeling, a construct, which is dissolving as many theoreticians ar gue (see “Home – a modern construct“). Or does its return in art and culture mean that it is an ideal worth bringing into the 21 st century? Do we understand culture as an intersubjective consciousness where ”experience becoming explanation, experiencing experienced as a way of explai ning” is the most obvious answer to the question (Connor 2000:4)? For sure, the bourgeois home will survive but it will be in a new, up-dated construct, which corresponds to the needs and demands the late modern man has in relation to house, family and community.

If we place these two recognitions opposite each other, the challenge to the future housing market will be to develop concepts that manage to build bridges between two conflicting needs: On the one hand the neccesity to move – physically, mentally, careerwise, aesthetically and socially – and on the other hand the need for rootedness, stability and set structures. This calls for a balance between flexibility and rootedness, individualism and community, outside and inside, private and public and a recognition of that fact that we are changing from being rooted in the traditional sense, to being rooted in networks of people and institutions, that span from the global to the local.

Literature:

Bech-Danielsen, Claus & Kirsten GramHanssen:”Home-building and identity – the soul of the house and the personal touch” IN Urban Lifescape , pp. 140 –

158, Aalborg University Press, 2004.

Benjamin, Walter: ”Louis –Philippe, or the Interior” (1939) IN Charles

Baudelaire. A Lyric Poet In The Era Of High Capitalism (1976), trans. Harry

Zohn, Verso, London, 1983.

Certeau, Michel de: Practice of Everyday Life , London, University of Minnesota

Press.

Conner, Steven & David Trotter (eds): Cultural Phenomenology , Critical

Quarterly, vol. 42, no. 1, spring 2000, Oxford.

Douglas, Mary: ”The Idea of home: A kind af space” IN Social Research, vol 58

(1), p. 287-307, 1991.

Gehl, Jan: Livet mellem husene. Udeaktiviteter og udemiljøer , Arkitektens

Forlag 1971 (2003).

Giddens, Anthony: Modernity and Selv-Identity. Self and Society in the Late

Moderne Age , Polity Press, London, 1991.

Heller, Agnes: ”Where are we at home?” IN Thesis Eleven , No 41, p. 1-18,

Massachusetts Institute of Tecnology, 1995.

Kumar, Krishan: ”Home: The premise and Predicament of Private Life at the end of twentieth century”, p. 204-236 IN Public and private in Thought and

Practice , (eds. K. Kumar og J. Weintraub), Chicago Press, 1994.

Mechlenborg, Mette: Hjemlighed. Mellem hjemmet og rejsen., final thesis,

University of Copenhagen, 2003.

Mechlenborg, Mette: ”Forestillingen om hjemmet” IN exhibition catalogue for

Hjemme igen . Ung svensk samtidskunst , ARKEN, 2002.

Mechlenborg, Mette: “Hvorfor er vi så optaget af vores hjem?” IN Kulturo ,

Copenhagen University, september 2005 (not yet published).

Michaëlis, Bo Tao: “Illusionernes egen godhed” IN Kritik (eds. Frederiks

Sjernfelt og Isak Winkel Holm), nr. 167, 2004.

Morley; David: Home Territories. Media, mobility and identity , Routledge,

London 2000.

Papastergiadis, Nikos: Dialogues of Diasporas , London, 1998.

Reed, Christopher (ed): Not at Home. The Suppression of Domesticity in

Modern Art and Architecture ., Thames and Hudson, London, 1996.

Rosenkrands, Jacob: “Hjemlighed er en ny megatrend” IN ”Boliglandet

Danmark”, Mandag Morgen , nr. 41, 2003.

Rønnow, Franz: “Parcelhuset er meningen med livet” IN ”Boliglandet

Danmark”, Mandag Morgen , nr. 41, 2003.

Tomlinson, John: Globalisation and Culture , Cambridge, Polity Press, 1999.

Winther, Ida Wentzel: Hjem & Hjemlighed – en kulturfænomenologisk feltvandring , Pd.h, Tha Danish University of Education, 2004.

Ærø, Thorkild: The Housing project of Denmark’s welfare society – ideal and needs related to housing” (2004) IN Urban Spaces , pp. 188-209, 2004,

Aalborg University Press, 2004.