Possible DRAFT Outline

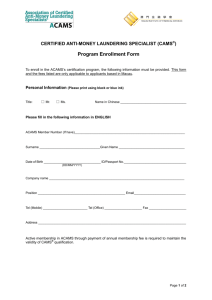

advertisement