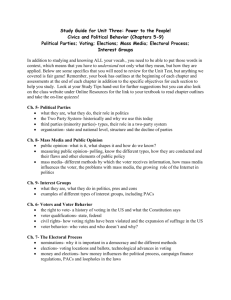

DOC 225KB - The Electoral Council of Australia

advertisement