An Exploraton of Baroque Music

advertisement

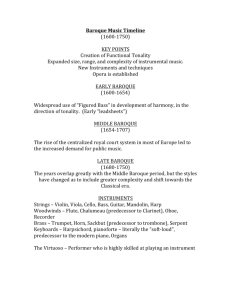

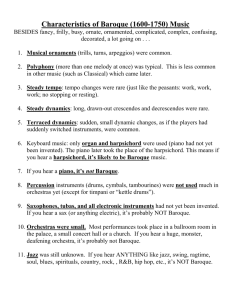

Larocque 1 Paul Larocque Professor Panaccione Elementary German I 18 December 2012 The Baroque: Music of Power The arts have a tremendous power to move people; be it visual art, literature or performing arts, or music, each has special qualities that touch the hearts and souls of individuals. Of the many branches of the arts, music is arguably the most powerful. Words can be misconstrued or lose their meaning, and visual art can often be misinterpreted or worse yet, underappreciated. Music, however, transcends time and space; it can lift one’s spirits in times of sadness, or bring us deeper into despair; it can be ethereal and ghost-like, as if being played by an orchestra of spirits, or it can be as joyous and heavenly as a choir of angels. Music is one of the few things in the world that has the power to touch everyone, regardless of race, ethnicity, age, or gender. Music can cross cultural boundaries and it can be inherently native all at the same time. No other genre or era in musical history has been as effective in each of these ways as baroque music. The combination of technical prowess and melodic variations, emotional highs and dramatic lows, and some of the most accomplished composers in history make the baroque period one of unparalleled renown and historic distinction. The term “baroque,” is derived from the Italian term “barocco,” meaning “bizarre,” and is used to describe the period in musical history from 1600-1750. It came to hold its modern definition in the mid-1900s; prior to that it was used strictly to describe the architecture of 17th and 18th century Europe, which is still an acceptable use of the term today. The period is one marked by political upheaval and religious unrest. During this time, the Roman Catholic Church Larocque 2 was attempting to ban Copernicus’ theory of the sun being the center of the universe, despite its increasing popularity. Also, the Protestant Reformation, spearheaded a century earlier by Martin Luther in Germany, gave rise to the Lutheran church, which played a major role in the music of Germany. In England, political turmoil was rampant. In 1649, Charles I was removed from the throne, tried by Parliament, and executed. A brief attempt at a Republic was set up under Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell, which also proved unsuccessful. Parliament restored the monarchy with Charles II and later James II, both of whom proved just as awful in the eyes of Parliament as their recent predecessors. Parliament decided to remove James II, and called on his daughter, Mary and her husband, William of Orange, to reign jointly, which they did beginning in 1689. Both monarchs were well-loved, and thus Parliament finally found a solution to their forty yearlong problem. During the baroque period, travel was (for those who could afford it), surprisingly quite common. Most composers took what was referred to as the Grand Tour, travelling to many different countries and meeting fellow composers. Another common reason for travel was patrons. Patrons were wealthy members of society who employed court musicians and/or composers, and would finance their works (usually composed for the patron or for an event he/she hosted), and provide lodging. Thanks to both the Grand Tour, and composers usually being employed by multiple patrons throughout their lives, many elements of national styles were introduced to other countries, and a common, musical baroque vocabulary was established. It is in this manner that Germany was introduced to the Italian sonata and concerto, popularized by Arcangelo Corelli and Antonio Vivaldi, and that Italy was introduced to the art of counterpoint and fugue, perfected in Germany by Johann Sebastian Bach. Also, George Frideric Handel, who was born in Germany, and studied with Corelli in Italy before moving to England, Larocque 3 introduced many of the national styles of Italy and Germany to the English nation. It should be noted that, interestingly, England was not fond of many of the Italian stylistic differences, and especially of Italian opera, as it was felt to be almost too sophisticated and unintelligible. Some of the major musical characteristics of the baroque era differ greatly from the medieval period and the Renaissance. First, composers in the baroque became more concerned with instrumentation, that is, what instrument should be used to play specific pieces. Previous to 1600, it was acceptable for musicians to choose what instrument they were going to play. Also, dramatic use of contrast was highly important in composing baroque music; the differences between loud and soft, soloist and ensemble, and various instruments all combine to create the majesty of the piece. Basso continuo, which is a base part underlying a piece of concerted music, played on a keyboard instrument, while accompanied by strings, was also a major component of baroque pieces. Composers favored instruments such as the harpsichord and violin, especially in Germany and Italy respectively. Arguably, J.S. Bach may have made use of the harpsichord more than any other baroque composer, and Corelli has been honored with the title – “Father of Modern Violin Technique.” During the baroque, polyphony was valued as a compositional element; it is the use of two or more voice parts, each having independent melody from the other, but both harmonizing with the other. Lastly, a variety of musical styles were popular including opera, oratorio, and cantata, all vocal, and sonata, concerto, and suites, which were instrumental. Almost every European country had prolific composers of their own, but perhaps four of the most prolific on the continent were Arcangelo Corelli, Antonio Vivaldi, Johann Sebastian Bach, and George Frideric Handel. Corelli (1653-1713), born in Fusignano, Italy, was a master of the baroque period. He influenced nearly every other major composer, including all of the Larocque 4 aforementioned men; often the Italy leg of the Grand Tour was not complete without a trip to visit Signore Corelli. (Although the same can be said of Vivaldi; Venice was a hotspot on the Grand Tour.) Corelli worked for a number of important musical patrons, but his most famous employer was Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni, nephew of Pope Alexander VIII. Cardinal Ottoboni was not only well known at the time due to who his uncle was, but also because he was a great patron of music, especially of Corelli (and later Vivaldi). However, he is even more famous in the historical record, as is Corelli, due to their atypically close bond, so close in fact, that Corelli left his entire estate to the Cardinal upon his death! Corelli, who is beyond famous now, was famous in his time as well. His music was some, if not the most popular in all of Europe. In addition to perfecting violin technique, earning him his aforementioned title, Corelli composed some of the best (and most numerous) concerti grossi of all time, earning himself the additional title of “Father of the Concerto Grosso.” His prowess with this type of piece is evidenced by the extensive sampling of other composers from his concerti, including Vivaldi and Bach. Vivaldi (1678-1741) was born in Venice, Italy, and ordained to the priesthood in 1703. His career as a priest was to be short-lived however, as after only one year he expressed the desire to stop celebrating the mass due to “tightness of the chest.” Some scholars posit that this health issue was merely an excuse to pursue a career in music; regardless of its legitimacy, it was arguably one of Vivaldi’s best decisions, as without it, the world would be devoid of his musical genius. In late 1703 – early 1704, Vivaldi began working for the Ospedale della Pietà, a boarding school for the illegitimate daughters of Venetian noblemen. Often referred to as orphanages, ospedali were nothing of the sort. Thanks to the generous donations from their “anonymous” benefactors, the girls in ospedali throughout Italy received a better education than some of the legitimate children of Italian nobles. Vivaldi remained a teacher for the Ospedale for a great deal of his Larocque 5 life; in fact, over seventy-three of his sonatas, and well over one hundred of his concertos were written for his students at the Ospedale. Vivaldi also worked for a number of musical patrons including Cardinal Ottoboni, and Louis XV of France. Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) was born into a very musical family in Eisenach, Thuringia, Germany; his father was the court trumpeter for the Duke. His father began teaching him to play harpsichord, but tragically both Bach’s mother and father passed away months from each other, when J.S. was only nine. Bach was taken in by his brother, Johann Christoph, who carried on his harpsichord lessons and also taught his younger brother to play the organ. At the age of eighteen, Bach decided to seek employment as an organist, which he successfully obtained in Arnstadt. After a leave of absence, and due to differences with the town council Bach resigned his post to seek employment elsewhere; he held a number of other positions in his life throughout Germany, but his greatest accomplishments were during his time in Leipzig as cantor and Kapellmeister at the Thomaskirche. As many of Bach’s positions were for the Lutheran church, much of his music is religiously based. He is arguably one of the greatest organ players in history, and is the greatest organist of the baroque period. (It is interesting to note that during his time as an organist in Weimar, he had a brand new organ rebuilt, simply because he felt it wasn’t large enough!) The year 1685 was a great year for music, as it was in this year that George Frideric Handel was also born. Handel (d. 1759) was born in Halle, Thuringia, Germany, and his father intended him for law. However, like Vivaldi, Handel had other ideas, and pursued a career in music; he was eighteen when he accepted a job as a violinist in Hamburg; a year later, a nineteen year old Handel had already staged his first two operas. Handel studied in Italy under Corelli, and also took the customary Grand Tour. It was during his travels that he met the influential Larocque 6 brother of the Elector of Hanover. In 1710 he was invited to visit Hanover, and was immediately appointed as Kapellmeister to the Elector, who proceeded to send Handel on a one year leave to London. Elector George Louis, was naturalized by an Act of Parliament in 1705, and ascended to the throne of England in 1714 as George I. Many of Handel’s more famous pieces were written during his time in England as Kapellmeister to the king, including “Water Music,” which was commissioned by George I for a concert on the River Thames. Shortly before the king’s death in 1727, Handel was naturalized and officially became a British subject. George I commissioned Handel to write four coronation anthems for his son’s coronation as King George II; the most famous (and only surviving anthem), “Zadok the Priest,” has been sung at every coronation since. Handel suffered two strokes in his lifetime, one in 1737, and again in 1743, but quickly bounced back from both, and continued composing and performing music. However, he lost his sight completely in 1752, which prevented him from writing new pieces, but he continued to perform his organ concertos based solely on memory alone. George Frideric Handel is buried in Westminster Abbey, London. The arts have a tremendous power to move people, and music can affect people like no other art form. The music from the baroque period is some of the most powerfully moving music in all of history, and the combination of technique, theory, and genius applied by its composers is truly remarkable. When coining the term for the era, the Italians described it perfectly as “barocco.” With the power to make us laugh or cry, enthrall us, chill us, and embed itself in our minds and hearts, baroque music truly has “bizarre” and magnificent powers. Larocque 7 Works Cited “Baroque Composers and Musicians: Antonio Vivaldi.” Sartorius, Michael. Baroque Music.org. Arton Internet Publications, n.d. Web. 18 Oct. 2012. <http://baroquemusic.org/ bqxvivaldi.html> “Baroque Composers and Musicians: Arcangelo Corelli.” Sartorius, Michael. Baroque Music.org. Arton Internet Publications, n.d. Web. 18 Oct. 2012. <http://baroquemusic.org/ bqxcorelli.html> “Baroque Composers and Musicians: George Frideric Handel.” Sartorius, Michael. Baroque Music.org. Arton Internet Publications, n.d. Web. 18 Oct. 2012. <http://baroquemusic.org/ bqxhandel.html> “Baroque Composers and Musicians: Historical Context, Geography, Biographical Notes.” Sartorius, Michael. Baroque Music.org. Arton Internet Publications, n.d. Web. 18 Oct. 2012. <http://www.baroquemusic.org/barcomp.html> “Baroque Composers and Musicians: Johann Sebastian Bach.” Sartorius, Michael. Baroque Music.org. Arton Internet Publications, n.d. Web. 18 Oct. 2012. <http://baroquemusic.org/ bqxjsbach.html> “Baroque Music.” Music of the Baroque. Music of the Baroque, 2012. Web. 5 Nov. 2012. <http://www.baroque.org/baroque/composers.htm> “Baroque Music.” Music of the Baroque. Music of the Baroque, 2012. Web. 5 Nov. 2012. < http://www.baroque.org/baroque/whatis.htm> “Baroque Music Defined.” Sartorius, Michael. Baroque Music.org. Arton Internet Publications, n.d. Web. 18 Oct. 2012. <http://www.baroquemusic.org/bardefn.html>