081-86A-0155 Trauma Casualty Assessment Eng LP Ver C

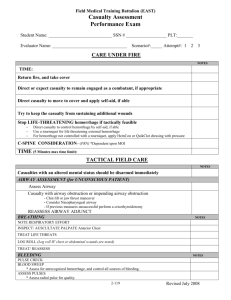

advertisement

PERFORM A TRAUMA CASUALTY ASSESSMENT 081-86A-0155 Purpose: This Training Support Package provides the instructor with a standardized lesson plan for presenting an introduction on the procedures for performing a trauma casualty assessment to the ANA Medical Company. Collective: Treat Unit Casualties References Number Title Date Additional Information: ANA STP 8-86C-E4-5-SM-TG, Soldier's Manual and Trainer's Guide MOS 86C, Mar 2008 ANA 4-02.2, Medical Evacuation, Feb 2009 ANA 4-25.11, First Aid, Jul 2009 STP 8-68W13-SM-TG STP 8-91W15-SM-TG Instructor Requirements: 1:20, MoD Defense Personnel, Contractor, ANA Personnel Instructional Guidance NOTE: Before presenting this lesson, instructors must thoroughly prepare by studying this lesson and identified reference material. Before class- This LESSON PLAN has practical exercises built throughout to check on learning or generate discussion among the group members. You may add any questions you deem necessary to bring a point across to the group or expand on any matter discussed. You must know the information in this LESSON PLAN well enough to teach from it, not read from it. SECTION II. INTRODUCTION Method of Instruction: Conference / Discussion or Practical/Hands on Technique of Delivery: Small Group Instruction Instructor to Student Ratio is: 1:20 Motivator An initial assessment and rapid trauma survey performed on a combat casualty assures that a comprehensive and systemic approach is used to evaluate trauma. With early identification and management of life threatening injuries, the soldier medic will be able to perform initial trauma stabilization that will ultimately save lives. Terminal Learning Objective NOTE: Inform the students of the following Terminal Learning Objective requirements. At the completion of this lesson, you [the student] will: ACTION: Perform a Trauma Casualty Assessment CONDITIONS: You encounter a casualty with multiple injuries. You will need sphygmomanometer, clean stethoscope, thermometer, airway adjuncts, oxygen, non-rebreathing mask, cervical collar, long spine board, scoop stretcher, and an ANA Form 1380 (Field Medical Card). STANDARDS: Assess the casualty, identify all life-threatening injuries, and manage him appropriately without causing further injury to the casualty. Perform the assessment in the correct sequence. A. ENABLING LEARNING OBJECTIVE ACTION: Medic will perform a general survey of the scene and a primary and secondary survey of the trauma casualty identifying all injuries in life threatening priority and stabilizing the casualty. CONDITIONS: You encounter a casualty with multiple injuries. You will need sphygmomanometer, clean stethoscope, thermometer, airway adjuncts, oxygen, non-rebreathing mask, cervical collar, long spine board, scoop stretcher, and an ANA Form 1380 (Field Medical Card). STANDARDS: Determine what injuries may be found based on the type of incident and does not cause further injury to the casualty Learning Step / Activity 1. Medical Personnel. Method of Instruction: Conference / Discussion Technique of Delivery: Small Group Instruction Instructor to Student Ratio: 1:20 Time of Instruction: 10 hrs Instructional Lead-In On the battlefield, rapid systematic assessment of a casualty increases the likelihood that lifethreatening injuries are identified and prioritized. If life threatening injuries are identified during the assessment, life saving treatment and interventions can be initiated immediately. SHOW SLIDE 1 PERFORM A TRAUMA CASUALTY ASSESSMENT 081-86A-0155 - A- REFERENCES: ANA-STP-8-86 ANA 4-02.2 ANA 4-25.11 STP 8-91W15-SM-TG STP 8-68W13-SM-TG SHOW SLIDE 2 Briefly detail the task, condition and standard to the students. Explain that this is performance based and that the students will be tested on this following this block of instruction. SHOW SLIDE 3 In this lesson, we will discuss some significant differences in care provided in a combat setting. It is also important to understand that performing the correct intervention must be performed at the correct time in combat care. A medically correct intervention performed at the wrong time on the battlefield can lead to additional casualties. The first step in this process is take appropriate body substance isolation (BSI) precautions. All body fluids should be considered potentially infectious. Always observe BSI precautions by wearing gloves and eye protection as a minimal standard of protection. The next step is to perform a scene assessment in which you determine the safest route to access the casualty, the mechanism of injury (MOI), and the number of casualties. You may need to request additional help, if necessary. Always take into consideration the need for spinal stabilization. If the MOI is significant, direct another Soldier to provide manual, in-line stabilization of the cervical spine. SHOW SLIDE 4, 5 Field assessments are normally performed in a systematic manner. The formal processes are known as the primary survey and the secondary survey. The primary survey is a rapid initial assessment to detect and treat life-threatening conditions that require immediate care, followed by a status decision about the patient’s stability and priority for immediate transport to a medical facility. The secondary survey is a complete and detailed assessment consisting of a subjective interview and an objective examination, including vital signs and head-to-toe survey. Communicate verbally with casualty to help establish immediate status of airway, breathing, circulation, and mental status. Perform an Initial Assessment to form a general impression (global overview) of the casualty's condition and environment. Attempt to determine the chief complaint. The primary survey is a process carried out to detect and treat life-threatening conditions. As these conditions are detected, lifesaving measures are taken immediately, and early transport may be initiated. For the critically injured casualty, the medic may never conduct more than a primary survey. The emphasis is on rapid evaluation, resuscitation, and the transportation to an appropriate medical facility. The primary survey is a “treat-as-you-go” process. As each major problem is detected, it is treated immediately, before moving on to the next. During the primary survey, you should be concerned with what are referred to as the ABCDE’s of emergency care: airway, breathing, circulation, disability, and expose. A-Airway: An obstructed airway may quickly lead to respiratory arrest and death. Assess responsiveness and, if necessary, open the airway. Insert airway adjuncts if needed and spinal immobilization if spinal injury is suspected. B-Breathing: Respiratory arrest will quickly lead to cardiac arrest. Assess breathing, and, if necessary, provide rescue breathing. Look for and treat conditions that may compromise breathing, such as penetrating trauma to the chest. SHOW SLIDE 6, 7 C-Circulation: If the patient’s heart has stopped, blood and oxygen are not being sent to the brain. Irreversible changes will begin to occur in the brain in 4 to 6 minutes; cell death will usually occur within 10 minutes. Assess circulation, and, if necessary, provide cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Also check for profuse bleeding that can be controlled. Use a loose tourniquet if necessary to control the bleeding. Assess and begin treatment for severe shock or the potential for severe shock. D-Disability: Serious central nervous system injuries can lead to death. Assess the patient’s level of consciousness by using the AVPU scale. E-Expose: You cannot treat conditions you have not discovered. Remove clothing– especially if the patient is not alert or communicating with you–to see if you missed any life-threatening injuries. Protect the patient’s privacy, and keep the patient warm with a blanket if necessary. As soon as the ABCDE process is completed, you will need to make what is referred to as a status decision of the patient’s condition. A status decision is a judgment about the severity of the patient’s condition and whether the patient requires immediate transport to a medical facility without a secondary survey at the scene. Ideally, the ABCDE steps, status, and transport decision should be completed within 10 minutes of your arrival on the scene. SHOW SLIDE 8 The secondary survey is a head to toe evaluation of the casualty. The medic will complete the primary survey, identify and treat all life-threatening injuries, and initiate resuscitation before beginning the secondary survey. The object of a secondary survey is to detect medical and injuryrelated problems that do not pose an immediate threat to survival but that, if left untreated, may do so. Unlike the primary survey, the secondary survey is not a ‘treat-as-you-go’ process. Instead, you should mentally note the injuries and problems as you systematically complete the survey. Then you must formulate priorities and a plan for treatment. A - Alert and oriented (eyes open spontaneously as you approach; casualty appears aware and responsive to the environment). V - Responsive to verbal stimuli (sound). P - Responsive to painful stimuli (touch, such as tapping the casualty on the shoulder or pinching the casualty's ear). U - Unresponsive (does not respond to any stimuli). SHOW SLIDE 9, 10 Determine casualty priority and make a transport decision. High priority conditions that require immediate transport include a poor general impression, unresponsive, responsive but not following commands, difficulty breathing, shock, complicated childbirth, chest pain with systolic blood pressure less than 100 mm Hg, uncontrolled bleeding, and severe pain. If the MOI is significant, perform a Rapid Trauma Assessment. Again, all life threatening injuries should have been identified and treated by this time. The goal at this stage is to identify and address any additional wounds. You may also identify signs or symptoms that will affect the long term evacuation or treatment of the patient as well. It is important that you carefully inspect the entire casualty. Using the head to toe method described below ensures you do not miss anything. Head: Inspect for deformities, contusions, abrasions, punctures or penetration, burns, tenderness, lacerations, and swelling (DCAP-BTLS). Palpate for tenderness, instability, or crepitus (TIC). Check the skull, eyes, ears, nose and mouth for any potential findings. At this time you should also reassess any treatments that have been performed. SHOW SLIDE 11 Neck: Check the neck to include the C-spine for any irregularities. Jugular vein distension and tracheal deviation are very late signs of tension pneumothorax (a condition you should have treated earlier). If, however, these are encountered at this stage, perform a needle decompression immediately. Inspect for DCAP-BTLS. Apply a cervical collar, if necessary SHOW SLIDE 12, 13 Chest: Inspect the chest for wounds. Expose the chest. For unconscious and trauma patients, you should completely remove clothing to expose the chest. (Try to provide as much privacy as possible for patients.) Look for obvious chest injuries, such as cuts, bruises, penetrations, objects impaled in the chest, deformities, burns, or rashes. If puncture or bullet wounds are found, check for exit wounds when inspecting the back. Examine the chest for possible fracture. Before you begin examining the chest for fractures, warn the patient that the examination may be painful. Begin your examination by gently feeling the clavicles (collarbones). Next, feel the sternum (breastbone). Then examine the rib cage by placing your hands on both sides of the rib cage and applying gentle pressure. This process is known as compression. If the patient has a fracture, compression of the rib cage will cause pain. Finally, slide your hands under the patient’s scapulae (shoulder blades) to feel for deformities or tenderness. Point tenderness, painful reaction to compression, deformity, or grating sounds indicate a fracture. If air is felt (like crunching popcorn) or heard (crackling sounds) under the skin, this indicates that at least one rib is fractured or that there is a pneumothorax (punctured lung). You may also observe air escaping the chest cavity and the wound when the patient has a punctured lung. Check for equal expansion of the chest. Check chest movements and feel for equal expansion by placing your hand on both sides of the chest. Be alert to sections of the chest that seem to be floating. (flailed chest) or moving in a direction opposite to the rest of the chest during respiration. Listen for sounds of equal air entry. Using a stethoscope, listen to both sides of the anterior and lateral chest. The sounds of air entry will usually be clearly present or clearly absent. The absence of air movement indicates an obstruction, injury, or illness to the respiratory system. Bubbling, wheezing, rubbing, or crackling sounds may indicate the patient has a medical problem or a trauma-related injury. Abdomen: Inspect the abdomen for wounds. Look for obvious signs of injury (e.g., abdominal distension, cuts, bruises, penetrations, open wounds with protruding organs (evisceration), or burns) in all four quadrants and sides. Palpate the abdomen for tenderness. Look for attempts by the patient to protect his abdomen (e.g., patient drawing up the legs). Gently palpate the entire abdomen. If the patient complains of pain in an area of the abdomen, palpate that area last. Do not palpate over an obvious injury site or where the patient is having severe pain. While palpating the abdomen, check for any tight (rigid) or swollen (distended) areas. Performing abdominal palpation is important because tender areas do not normally hurt until palpated. Note if pain is localized, general, or diffused. SHOW SLIDE 14, 15 Pelvis: Examine the pelvis for injuries and possible fractures. Examine the pelvic area for obvious injuries. Next, gently slide your hands down both sides of the small of the patient’s back and apply compression downward and then inward to check the stability of the pelvic girdle. Note any painful responses or deformities. If a grating sound is heard, the injury may involve the hip joint, or the pelvis may be fractured. Note any obvious injury to the genital region. Look for obvious injuries, such as bleeding wounds, objects impaled in the area, or burns. Also, check for priapism in male patients. Priapism is a persistent erection of the penis often brought about by spinal injury or certain medical problems, such as sickle cell crisis. SHOW SLIDE 16, 17 Extremities: Since you are already at the pelvis, palpate the lower extremities first then the upper extremities using the same process (DCAP-BTLS). Examine the lower extremities. DO NOT move, lift, or rearrange the patient’s lower extremities (legs and feet) before or during the examination as further injury to the patient may occur. Check for signs of injury by inspecting each limb, one at a time, from hip to foot. Rearrange or remove clothing and footwear to observe the entire examination site. Pants should be removed in a manner that does not aggravate injuries. Cutting along the seams to remove pants is the best method. If the injury is not obvious, remove the shoe(s) and palpate any suspected fracture sites for point tenderness. Before palpating the site, warn the patient that this examination may cause pain. Before the patient is moved, all suspected or known fractures should be stabilized (with splints, traction splints, or the like). Examine the upper extremities for injury. Check for signs of injury to the upper extremities (arms and hands) by inspecting each limb, one at a time, from clavicle to fingertips. Rearrange or remove items of clothing to observe the entire examination site. Check for point tenderness, swelling, or bruising. Any of these symptoms may indicate a fracture. Immobilize any limb where a fracture is suspected. Check for a distal pulse and capillary refill. To make sure the circulation to the upper extremities has not been compromised, confirm distal (radial) pulse. Initial check of radial pulse was performed during the primary survey. Check capillary refill of fingers or palm of hand (see step 21 for procedure). If there is no pulse or if capillary refill is delayed, the patient may be in shock or a major artery supplying the limb has been pinched, severed, or blocked. Check for nerve function and possible paralysis of the upper extremities (conscious patient). Check the upper extremities of conscious patients for nerve function or paralysis. Have the patient identify the finger you touch, wave his hand, and grasp your hand. Do this to both hands. If the patient cannot feel your touch or the sensations in each hand are not the same, assume nerve damage in the limb or a spinal injury has occurred. SHOW SLIDE 18, 19 Posterior: (If not already done): If the patient is unconscious or you suspect C-Spine injury (based on MOI) you should log roll the patient. Examining the posterior is not simply the back; remember that rectal bleeding is a sign of internal hemorrhage. This should be checked as well. Reassess ALL interventions following a log roll! Perform a focused history and physical exam based on chief complaint. Focus on the areas the casualty tells you are painful or that you suspect may be painful due to the MOI. SHOW SLIDE 20, 21 A set of complete vital signs should be taken. Depending on the situation, a second medic may obtain vital signs while the first medic completes the survey. A complete set of vital signs include temperature, pulse, blood pressure and respirations. This should be done every 3-5 minutes while the patient is being evacuated. The Medic will perform a quick history on the casualty. This information should be recorded on the field medical card and passed on to the Medical Treatment Facility. You will get his information from the casualty or bystanders who know the casualty. Use the mnemonic SAMPLE to remind you of the questions. S-Signs/symptoms - Ask the casualty what is wrong. Observe the casualty. A-Allergies - Are you allergic to any medication or anything else? SHOW SLIDE 22, 23 M-Medications - Are you currently taking any medication? P-Previous medical history - Have you been having any medical problems? Have you been feeling ill? Have you been seen by a physician recently? SHOW SLIDE 24, 25 L-Last meal -When did you eat or drink last? (Keep in mind, food could cause the symptoms or aggravate a medical problem. Also, if the patient requires surgery, the hospital staff will need to know when the patient has eaten last.) E-Events -What events led to today’s problem (e.g., the patient passed out and then got into a car crash)? SHOW SLIDE 26, 27 Perform a Detailed Physical Examination. This is done only if time permits during casualty evacuation (CASEVAC) or while waiting for CASEVAC, if not performing life-saving interventions. Do not delay evacuation to perform this exam. Scalp and cranium: Inspect the scalp for wounds. Use extreme caution when inspecting the scalp for wounds. Pressure on the scalp from your fingers could drive bone fragments or force dirt into wounds. Also, DO NOT move the patient’s head, as this could aggravate possible spinal injuries. To inspect the scalp, start at the top of the head and gently run your gloved fingers through the patient’s hair. If you come across an injury site, DO NOT separate strands of the hair. To do this could restart bleeding. When the patient is found lying on his back, check the scalp of the back of the head by placing your fingers behind the patient’s head. Then slide your fingers upward toward the top of the head. Check your fingers for blood. If a spinal or neck injury is suspected, delay this procedure until the head and neck have been immobilized. Furthermore, if you suspect a neck injury, DO NOT lift the head off the ground to bandage it. Ears: Inspect the ears for injury and the presence of blood or clear fluids. Without rotating the patient’s head, inspect the ears for cuts, tears, or burns. Use a penlight to look in the ears for blood, clear fluids, or bloody fluids. Blood in the ears and clear fluids (cerebrospinal fluid) in the ears are strong indicators of a skull fracture. Also, check for bruises behind the ears, commonly referred to as Battle signs. Bruises behind the ears are strong indicators of skull fracture and cervical spine injury. SHOW SLIDE 28, 29 Face: Check the skull and face for deformities and depressions. As you feel the scalp, check for depressions or bony projections. Visually examine facial bones for signs of fractures. Unless there are obvious signs of injury, gently palpate the cheekbones, forehead, and lower jaw. Eyes: Examine the patient’s eyes. After examining the face and scalp, move back to a side position. Begin your examination of the eyes by looking at the patient’s eyelids. Do not open the eyelids of patients with burns, cuts, or other injuries to the eyelid(s). Assume there is damage to the eye and treat accordingly. If eyelids are not injured, have patients open their eyes. To examine the eyes of unconscious patients, gently open their eyes by sliding back the upper eyelids. Keep in mind, pressure applied to the eyelid may cause further injury. When the eye has been opened, visually check the globe of the eye. Check the pupils for size, equality, and reactivity. Using a penlight or flashlight, examine both eyes. Note pupil size and if both pupils are equal in size. Also, see if the pupils react to the beam of light. Note a slow pupil reaction to the light. Look for eye movement. Both eyes should move as a pair when they observe moving persons or objects. Nose: Inspect the nose for injury and the presence of blood or clear fluids. Without rotating the patient’s head, inspect the nose for cuts, tears, or burns. Use a penlight to look in the nose for blood, clear fluids, or bloody fluids. Clear fluid (cerebrospinal fluid) in the nose is a strong indicator of a skull fracture. Burned or singed nasal hairs indicate possible burns in the airway. SHOW SLIDE 30 Mouth: Inspect the mouth. Look inside the mouth for signs of airway obstruction that may not have been observed during the primary survey (e.g., loose or broken teeth, dentures, and blood). When you inspect the mouth, remember not to rotate the patient’s head. Smell for odd breath odors. Place your face close to the patient’s mouth and nose and note any unusual odors. A fruity smell indicates diabetic coma or prolonged vomiting and diarrhea; a petroleum odor indicates ingested poisoning; and an alcohol odor indicates possible alcohol intoxication. SHOW SLIDE 31, 32 Neck: Inspect the anterior neck for indications of injury and neck breathing. This procedure consists of exposing the anterior neck to check for injury and to detect the presence of a surgical opening (stoma) or a metal or plastic tube (tracheostomy). The presence of a stoma or tracheostomy indicates the patient is a neck breather. Also, if you have not already done so in the primary survey, check for a medical identification necklace. A necklace may state the patient has a stoma or tracheostomy. Look for signs of injury, such as the larynx or trachea deviated from the midline of the neck, bruises, deformities, and penetrating injuries. Also, check for distention of the jugular vein. If the jugular vein is distended, there may be an airway obstruction, a cervical spine injury, damage to the trachea, or a serious chest injury. All of these conditions require immediate medical care. After the anterior neck is inspected and if a spinal injury is suspected, apply a rigid cervical or extrication collar. If the patient is unconscious, assume the patient has a spinal injury. Chest: In addition to checking for DCAP-BTLS, you should also attempt to auscultate the chest if the tactical situation permits. Simple rib fractures and flail chest segments should be treated at this time. Reassess any previous treatments, including needle decompression or occlusive dressings, which may have already been performed. SHOW SLIDE 33, 34 Reassess the abdomen: In addition to inspecting for DCAP-BTLS you should also palpate for Tenderness, Rigidity or Distension. Abdominal eviscerations should be treated appropriately. Signs of internal hemorrhage, while not treatable on the battlefield, may effect your decision during casualty evacuation Reassess the pelvis: The patient’s pelvic area is obviously deformed, DO NOT PALPATE IT, as you will likely cause further instability and damage. Gently compress (downward or inward) to detect TIC. Inspect for priapism. If a conscious casualty complains of pain or if an unconscious casualty responds as if in pain at any time during the assessment, do not continue the exam. Treat for pelvic fracture. SHOW SLIDE 35, 36 Reassess the extremities. palpate the lower extremities first then the upper extremities using the same process (DCAP-BTLS). Note and treat any minor injuries not already addressed. Reassess any major interventions already performed, especially tourniquets or pressure dressing. Reassess the posterior. If the patient is unconscious or you suspect C-Spine injury (based on MOI) you should log roll the patient. Examining the posterior is not simply the back; remember that rectal bleeding is a sign of internal hemorrhage. This should be checked as well. Reassess ALL interventions following a log roll! SHOW SLIDE 37 Manage secondary injuries and wounds appropriately. Reassess the casualty's vital signs every 5 minutes (if unstable), every 15 minutes (if stable). SHOW SLIDE 38, 39 On the battlefield, rapid systematic assessment of a casualty increases the likelihood that life threatening injuries are identified and prioritized. If life threatening injuries are identified during the assessment, life saving treatment and interventions can be initiated immediately. It is essential to assess casualties in a systematic way that allows for quickly finding and treating immediate threats to life. This search is called the initial assessment. By forming a general assessment, determining mental status, evaluating airway, breathing, and circulation and determining the casualty's priority, you can find and correct the problems that could otherwise end a casualty's life in just a few minutes.