outline, literature review, women & welfare project

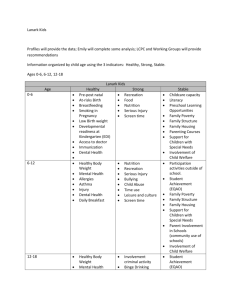

advertisement