- American Society of Victimology

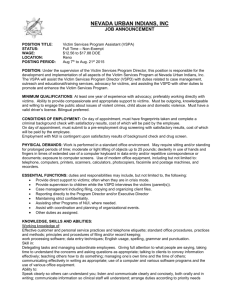

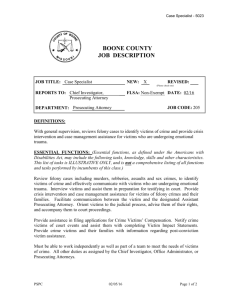

advertisement