The Epicurean Concern about the Death and the Future

advertisement

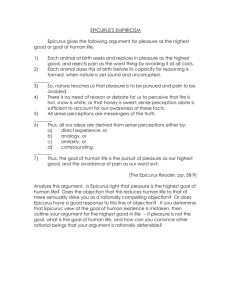

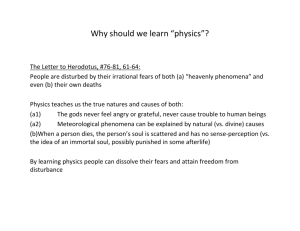

Milosz Pawlowski The Epicurean Concern about the Death and the Future. While to most laymen the Epicurean arguments about death are one of the most paradoxical and bizarre pieces of philosophical reasoning, they have always provoked a deep interest and respect of great many philosophers. Many of them, especially in more recent times, reject the Epicurean position and the arguments. Yet Epicurus has some committed defenders as well. In most of the recent debates, the Epicurean arguments are by and large treated as self-standing and quite amenable to reconstruction in modern terms. I do not wish to deny that Epicurean arguments are fairly clear. But I think that their full force, especially in face of some powerful objections, can be appreciated only if one sees them as a part of the overall Epicurean view of life. As some modern commentators keenly pointed out, it is a highly peculiar view of life1. What is often seen as the most problematic is the peculiar Epicurean attitude towards the duration of pleasure and of happy life2. The problems with this attitude are internal to Epicureanism (contrary to what some defenders of Epicureanism seem to think). But I will try to show that they can be overcome. Epicurean attitude to life and death is consistent and not without appeal. Although that appeal might well depend on temperament, as Williams remarks. In the first part of the paper I develop an outline of the basic structure of Epicurean ethics, which will make it possible to clearly present and solve the problems pertaining to Epicurean concerns about pleasant life and its duration. The Basic Structure of the Epicurean Ethics Epicureanism is a teleological, or in modern terms, a consequentialist ethical theory. In such theories, the basic moral concern is to achieve/instantiate valuable state of affairs. In antiquity, the goal was often specified in terms of the good, which is a property rather than a state of affairs. Nonetheless, one is morally concerned with instantiating this property in one’s life i.e. with bringing about states of affairs in which the good is present. Every consequentialist theory has to contain basic principles of three kinds. What comes first is specification of intrinsic good. It should be noted that the predicate “good” in Epicureanism (as perhaps in all other Greek schools) is a relational predicate. Something is always good for somebody. This relativization to a moral subject should be borne in mind, though I shall often omit to express it for the sake of brevity. In Epicureanism the intrinsic good is identified with pleasure: (P1) For any property P, P is an intrinsic good P belongs to the class of pleasures3 1 See esp. Nussbaum, The Therapy of Desire and Williams, The Makropulos Case. Rosenbaum sets out this central issue very well in his Epicurus on Pleasure... 3 This formulation leaves open all the question about the nature of pleasure; whether there is just one first order property of individuals of, say “experiencing pleasure”; or is “pleasant” predicated of states, or properties of experience; whether there are many varieties of pleasure and so forth. 2 What is good are states of affairs in which which pleasure is instantiated or contained: (P2) S is good S contains a P which is a pleasure The second set of principles should allow us to compare values and valuable states of affairs. One can regard such principles as definitions of predicates “better” and “the best”. (P3) For all P1, P2 which are pleasures (P1 is better than P2 P1 more pleasant than P2) (P4) P is best P is most pleasant (P5) S1 is better than S2 S1 contains more pleasure than S2 (P6) S is best S instantiates the best pleasure Once we are clear about values, we would also like to know what to do about them. An ethical theory has to contain principles determining the moral value of our acts, choices, desires, dispositions etc. As Epicurus often talks about prudent choices4, I use the terminology of preference and choice. (P7) If S1 is better than S2 then it is rational to prefer S1 to S2, and it is irrational to prefer S2. (P8) It is rational to prefer most the best state of affairs for oneself, i.e. happiness. (P9) For all actions A, B, which X can perform (X should choose to do A rather than B A is expected to lead to a better state of affairs for X than B). (P10) The final end of every action is to achieve the best state of affairs (happiness). I have deliberately left the last principle slightly vague. The main problem of my essay will be the explanation how to reconcile the fact that happiness is the telos of life and that it does not matter how long one enjoys it. Let us first try get clearer about the other principles. For somebody familiar with modern consequentialism, (P7)-(P10) might look like ordinary principles of maximization of the good outcomes. And in modern theories, maximization of good outcomes is ususally aggregative: the amount of good is summed over times (and over persons, but that obviously is not the case in Epicureanism). The following words of Epicurus seem to strongly favour just such interpretation: we do not choose every pleasure either, but we sometimes pass over many pleasures in cases when their outcome for us is a greater quantity of discomfort; and we regard many pains as better than pleasures in cases when our endurance of pains is followed by a greater and long-lasting pleasure5 And yet this interpretation is untenable when we look at other important fragments: the wise man… just as he chooses the pleasantest food, not simply the greater quantity, so too he enjoys the pleasantest time, not the longest6. 4 5 See esp. LM 5, 6 (L&S 21 B) on prudence as the principal virtue. LM 3 (L&S 21 B). Unlimited time and limited time afford an equal amount of pleasure, if we measure the limits of that pleasure by reason7. Accordingly, “more pleasure” in (P5) should be taken to mean “better pleasure” and not “bigger sum of pleasures over time”. What matters, is the quality of one’s life; its duration is in principle irrelevant. But there is a reason why Epicurus mentions longlasting pleasure in the first fragment. To attain true pleasure we need two things: satisfaction of bodily needs (that is aponia) and fredom from fear, a sense of security (ataraxia). Therefore the state of affairs which is expected to contain some pleasure at the beginning, but a lot of pain in the end, cannot be regarded as best. If we take temporally extended states of affairs (including the whole life), what matters is not only that it contains pleasure, but also the ratio of pleasure and pain, and their temporal distribution8. It is thus possible to understand how the basic principles work. But the question arises whether they provide a sensible account of human concern about happiness. The problem of intelligibility of the Epicurean concern about the future We are told that our inborn, natural and morally fundamental desire, and the goal of our life, is to achieve the highest pleasure, happiness, which consists in the absence of pain and mental disturbance (aponia, ataraxia). So far, so good. Yet we are also told that once we achieve this state it does not matter at all whether we keep and cherish it, or loose it by dying. And this certainly has an air of paradox. Why, we might ask, should we strive so much, as Epicurus wants us to, to achieve something which we then could calmly abandon without the slightest regret? Augustine points out that if we are indifferent to the prospect of loosing something, we cannot be sensibly said to love it9. Bernard Williams makes a similar point about desires: “To want something, we might also say, is to that extent to have reason for resisting what excludes having that thing: and death certainly does that, for a very large range of things that one wants. If that is right, then for any of those things, wanting something itself gives one a reason for avoiding death... , and hence to regard death as something to be avoided; that is, to regard it as an evil.” The very last conclusion might well go too far, but altogether this is one of the most challenging objections to Epicureanism. Rosenbaum tries to reject this sort of criticism on the grounds that even if a desire for prolonging the enjoyment of happy life is widespread and perhaps even natural, this does not show that it is a rational desire, a desire we should have10. At best, it is a natural but unnecessary desire, according to Epicurus’ classification. This response, though it seems to capture well some important aspect of Epicurus’ position, is not adequate. Rosenbaum underestimates the force of the objection. For its proper conclusion is that insofar as the Epicurean attitude to pleasant 6 LM 6 (L&S 24 A). KD 19 8 See Vat. XLVIII. 9 De Trin., XIV,19,26. In this fragment of De Trinitate ‘love’ is a very broad term, roughly synonymous to ‘want’ or ‘desire’. 10 Rosenbaum, Epicurus on Pleasure… 7 life lacks the necessary structure of a serious desire, it is either unintelligible, or at least it is something so far removed from our ordinary desires as to be irrelevant as a serious analysis of our moral concerns. For a theory which allegedly takes human nature as a starting point and criterion in ethics, that would be a fatal defect. In order to meet this challenge, it is necessary to work out a consistent account of the structure of the Epicurean concern and of the role assigned to the time-factor. The most straightforward interpretation of the Epicurean concern about the future would be to say that at each time, everybody should a) choose to bring about better states of affairs rather than worse b) make choices which lead to his attainment of happiness now and in the future. It is an open question whether we can be morally concerned with attaining happiness now – for it either is attained, or not, and we enjoy it, or not. In any case, a concern for the future has to be there as well, if this is to be an intelligible teleological concern. Now, under the current interpretation, it turns out that one always necessarily desires to prolong life in order to attain happiness. That is just what Williams maintained. At this point, a defender of Epicureanism can point out that we have some desires which exhibit an altogether different structure. We might call them achievement-desires. The examples might be those of climbing Mount Everest or winning the Olympics, or perhaps, tasting a good wine. Nobody wants to climb Mount Everest forever, nor stay on top for too long, for that matter. What matters, is the achievement of the goal in one’s life-time; and very often one occasion is quite enough. It might admittedly seem to be a rather strange analysis of the concern for happiness. But that is probably due to a nonEpicurean conception of happiness which most of us have. There is a more important problem with this proposal, however. It is natural to construe such desires as temporally neutral. What matters, is the attainment of something at some point in one’s life, and, all other things being equal, it does not matter whether the achievement is located in one’s past or in one’s future. This cannot be the case, however, with the Epicurean concern with happiness: We must try to make the end of the journey better than the beginning, as long as we are journeying; but when we come to the end, we must be happy and content. 11 It seems to me that the very fact that Epicureanism is a teleological theory, makes it impossible for it to involve temporal neutrality of concerns. The telos of one’s life is not something which can be achieved and then passed over. It is either actually enjoyed or it is to-be-achieved in the future. That one were once happy does not make one better off if one is no longer happy now. Secondly, having a temporally neutral attitude towards pains would make us more miserable. An important point in the Epicurean therapy is that severe pains are soon over12. That would be no consolation if it would be bad just to have pains in one’s life-history. Finally, the starting point for Epicurean ethics is analysis of human nature and our natural psychological makeup. It seems to me that it was something altogether obvious for Epicurus that we are predominantly concerned about (or biased for) the future. There are some fascinating Epicurean fragments about the 11 12 Vat. XLVIII. KD 4. attitude towards the past13, but one does not find there a claim that our concerns should be temporally neutral. Rather, one should adopt a particular attitude towards the past14. Thus the two simple interpretations of the Epicurean attitude towards future have failed. In order to provide a solution, we need to move deeper into the substance of the Epicurean ethics. I will sketch an interpretation which takes the presentness of value and satisfaction of desires as the key elements of Epicurean hedonism. The structure and nature of Epicurean concerns As I have already remarked, the good in Epicureanism must be something for somebody. I think it is plausible to say that for Epicurus this implies that good must be something present for somebody. Several fragments support this idea. In the first place, it is true that evil has to be present. In the Letter to Menoeceus, Epicurus presents a famous argument againsts the badness of death: Therefore that most frightful of evils, death, is nothing to us, seeing that when we exist death is not present, and when death is present we do not exist 15. The alleged evil can matter only insofar as it can be present for us. There seem to be no reason why the same should not hold for the good. And indeed, this would explain why such things as fame, erection of statues or, for that matter, whatever happens after our death, does not matter. Of course, we can obtain the same result if we apply the principle that only experience can be good or bad for somebody. Certainly, the presentness and experiential character of the good go hand in hand – experiencing something is the most obvious way of making something present. I would insist, however, that presentness has a sort of priority. There are important goods which are not strictly speaking experienced, but recollected. It is important to appreciate the subtlety of Epicurus’ approach to the past. The good things in the past were certainly experiences. And it is an actual good experience that I recollect a good experiences in the past. That is why it can contribute to my present well being. But this recollection seems to be pleasant precisely in virtue of making firmly present the goodness of past things: It is not the young man who should be thought happy, but an old man who has lived a good life... good things... he has brought into safe harbour in his grateful recollections16. [the old] ...with advancing years, they may remain young in blessings through the joyous recollection of things past17. 13 Vat. XVII, Vat. LXXV; Seneca Ep. XIII, 16; Ep. XV, 9. If I am right that Epicureans cannot really advocate temporal neutrality, then that is an additional reason for not taking Lucretius’ Symmetry Argument to be directed against the asymmetry of our attitudes. See Warren, chp. 3. 15 LM 5, L&S 24 A. 16 Vat. XVII. Cf . Vat. LXXV: “Ungrateful towards the blessings of the past is the saying, ‘Wait till the end of a long life’.”; and also in Seneca Ep. XIII, 16: “Among the rest of his faults the fool has also this: that he is always beginning to live.”; Ep. XV, 9: “The fool’s life is ungracious and fearful: it is directed totally at the future.”. 17 LM, Gaskin, p. 42. 14 We must heal our misfortunes by the grateful recollection of what has been and by the recognition that it is impossible to make undone what has been done 18. Now, the idea that the good must be something enjoyed in the present, seems to afford a plausible and attractive explanation of some difficult passages: It takes just the same time for the greatest good to be created and for it to be enjoyed19. Unlimited time and limited time afford an equal amount of pleasure, if we measure the limits of that pleasure by reason20. ...even in the hour of death, when ushered out of existence by circumstances, the mind does not lack enjoyment of the best life21. As we have seen, Epicurus maintains that extended duration does not make the good better. That is, the good does not admit of temporal aggregation. Now, we can observe that the sum of goods over time is never actually experienced as such. We always have only present experiences. This provides a powerful argument for Epicurus claim in KD 19, which, in the light of remark about the ‘hour of death’ in KD 20, I take to mean that even minimally short experience of the good we are capable of is as good as arbitrarily long enjoyment of the same good. 1. A subject necessarily has experiences successively. At each time, only some of his experiences are present. 2. A temporal aggregate of experiences contains a larger amount of goods than any of its minimal intervals of experience. 3. But it is not possible to experience a temporal aggregate of experiences as a whole (in virtue of 1). The only way it can be experienced is through experience of its minimal intervals. 3. Every good necessarily has to be experienced. 4. The only amount of good contained in the aggregate which can ever be experienced is the good contained in particular minimal intervals. (by 3) 5. Therefore the experience of the aggregate and the experience of a minimal interval contain the same amount of good. 6. Therefore the aggregate and the minimal interval contain the same amount of good. Corollary: 7. The sum of the goods over times cannot be experienced, hence it is not strictly speaking a good at all. The desire to merely extend one’s life is unnecessary. This arguments shows that in strictly experiential terms, in terms of what is experientially present to a subject, the duration of life indeed does not increase experienced good. 18 Vat. LV. Vat. XLII. 20 KD 19 21 KD 20 19 Yet even if one maintains that only the actual states of mind matter, there is still a question of their content. And this content is largely determined by recollections and expectations, as Epicurus himself is keen to assert. Now, one can argue that it is much better at every point in time to have recollections of many past fruitful years and a confident expectation of dozens, or hundreds, or infinitely many, good years to come, than not to have them. This challenge has to be answered by analyzis of desires and their satisfaction. Again I admit that my interpretation is slightly speculative. I claim that something is good for somebody if and only if it satisfies the desires or needs she presently has22. This claim fits well some central texts about pleasure, but does not straightforwardly follow from them either23. There are, however, two indirect arguments for this interpretation. The first is based on Epicurus teaching on empty desire. For if something causes no distress when present, it is fruitless to be pained by the expectation of it24. The fundamental idea is that in our concern about the future (and also about the past in the case of Lucretius), we should look at what is involved in the presence of the state we are concerned about: Every desire must be confronted with this question: what will happen to me, if the object of my desire is accomplished and what if it is not? 25 Projects might be about future, but their fulfilment does not make the self in the past any more better off or not – it is good for the self who can actually enjoy their fulfilment. And if the future self is really to enjoy their fulfilment, he must retain the desire. This is probably the case only with natural desires. Lucretius describes with great mastery the frustrated lives of ordinary men, who, ignorant of their true needs, hit upon random desires. In the very moment that they achieve what they have desired, they experience a change of heart, and thus they are never truly satisified26. As Epicurus observes, the life directed totally at the future can never be happy27. The idea that our concern about our future is based on a sympathetic imaginative identification with the perspective of our future self (which might, however, often go wrong), seems to be central for Lucretius’ thanatology and psychology of fear of death. It underlies his analyzis and criticism of feelings of people troubled by unpleasant I say “desires and needs” because happiness involves not being hungry, thirsty etc. If we are in this state, we do not have a desire to drink, which would be satisfied. But at each time the body has a need for water, food etc., be this need satisfied or not. If this usage is not appealing, we could also say that we have a natural desire not to be thirsty etc., and this is satisfied. 23 LM 1,2; Vat. XXXIII. 24 LM 4. 25 Vat. LXXI. 26 DRN, III 1053-1075. Cf. Vat. XXXV: “We should not spoil what we have by desiring what we have not...”. 27 Vat. XIV: “But you, who are not [master] of tomorrow, postpone your happiness: life is wasted in procrastination and each of one dies without allowing himself leisure”; cf. Seneca Ep. XIII, 16: “Among the rest of his faults the fool has also this: that he is always beginning to live.”; Ep. XV, 9: “The fool’s life is ungracious and fearful: it is directed totally at the future.”. 22 imaginations of the desintegration of the body28 and of the grief of mourners29. The only things which we can sensibly be concerned about are those which satisified the desires we had, satisfy the desires we have now, and will satisfy the desires we will have. If, for whatever reason, we happen at some time not to have desires, we neither are then concerned about anything, and nothing then is good or bad for us, nor do we have any reason now to be concerned when thinking about our state at that time. This is so in the case of our prenatal nonexistence. The same is true of death: one does not miss any good things30 and suffers no evil, and thus there is nothing good or evil for one then. But even more interestingly, Lucretius claims that if within our life there are moments when we do not have desires, then it does not matter to us whether we live or not: For never does any man long for himself and life, when mind and body alike rest in slumber. For all we care, sleep may then be never-ending, nor does any yearning for ourselves then beset us 31. It seems that even though we exists, since we are in a state of de facto total indifference to everything, nothing which would happen is good or bad from our perspective then. And we neither regret that we had slept in the past, nor are afraid of being in this state in the future. Thus dream offers an even more powerful analogy to death than prenatal nonexistence, as it can be in the future and apparently in all relevant ethical respects is just like death. What we have said so far allows us to answer some of the worries about the Epicurean attitude to life and death. The Epicurean tenet that death is not fearful cannnot be touched by objections, if we allow that it is rational that our concern about the future states should be shaped by the understanding of what it would be like for them to be present. In general, even if we have a reason to avoid something because we prefer something else, this in no way shows that we have a reason to be afraid of the nonpreferred outcome. The choice might be between a good and a neutral state. That is why Williams goes too far in claiming that death is evil on the basis of his argument. But for all that, we might always prefer to go on living, even if we are not afraid of death. The reason why Epicureans actually reject the preference for longevity might be nonetheless very simple. Given the nature of the world, the desire to live always simply cannot be met. And even the desire to live a humanely long life is quite likely to be frustrated by causes beyond our control. Therefore, even if the desire to extend one’s pleasure is not in itself irrational, the attachment to this desire is likely to produce uncertainty and disturbance in the soul, thus spoiling the happiness it could enjoy now32. Still, we might feel that this is just making the best of an objectively bad situation. If we are allowed to be concerned about our future at all, why should we calmly accept an arbitrarily and externally imposed limit on this concern? And if joyful recollections of a long life can outweigh even a terrible pain, would not a recollection of an even longer and more fruitful life, and an expectation of its long continuance be an even greater good? This challenge has still not been met. Why the happy and complete life apparently remove the concern about its prolongation? 28 DRN III, 870-893. DRN III, 894-911. 30 DRN III, 900-901. 31 DRN III, 919-922. 32 Rosenbaum, Epicurus on Pleasure, alludes to this possibility. 29 Let us look at two fragments which are among central Epicurean texts about happiness: The flesh cries out to be saved from hunger, thirst and cold. For if a man possess this safety and hopes to possess it, he might rival even Zeus in happiness33. ...to refer every choice and avoidance to the health of the body and the soul’s freedom form disturbace, since this is the end belonging to the blessed life. For this is what we aim at in all our actions – to be free from pain and anxiety. Once we have got this, all the soul’s tumult is released, since the creature cannot go as if in pursuit of something it needs and search for any second thing as the means of maximizing the good of the soul and the body. For the time when we need pleasure is when we are in pain from the absence of pleasure. <But when we are not in pain> we no longer need pleasure34. Aponia and ataraxia is thus a state of complete satisfaction, or, we might say, satiation of our needs and desires. The crucial idea seems to be that once a need is satisfied, it actually ceases to be. The feeling of need implies that one is in a bad state. I would even claim that insofar as one feels a need, one feels a non-satisfied need, and eo ipso, is in a bad, painful state. Happiness seems to be a state without any need – and thus without any frustration or worry. Hence the need to prolong one’s life is also absent. Just like a guest at the banquet who have eaten and drunk to the full35, the happy man feels free and indifferent whether to go or to linger. But perhaps it still is not clear how feeling satiated now can prevent one from being concerned about one’s future well-being. To grasp this, let us start form the beginning. Let us say, that the satisfaction of basic needs is the basic good and the nonsatisfaction of basic needs is the basic evil. When one feels a need, feels that something is lacking, one has a forward-looking desire for the satisfaction of that need (that is, a desire for the pleasure, for the good). When one does not feel it, one does not have this desire either. When one happily enjoys the good, one feels no lack of more of basic good (for this feeling would be frustrating, and thus would render one unhappy, contrary to the assumption). So far we were talking only about basic, bodily desires. Yet we also have a rational forward-looking desire to avoid painful states in the future. That is the basic mental need for security36. Taking into account also what we have said previously about the structure of our concern about the future, we might say now, that we have a reason to be concerned about the future only insofar as we either: a) have immediate forward-looking desires pertaining to bodily needs b) expect to have desires in the future which can be frustrated. Insofar as we feel threatened by pain in the future, we have a forward-looking desire for obtaining the means for protection against such harms (i.e. we want security). But, analogously to the case with bodily needs, once we have actually achieved the sense of security and freedom from fear, we no longer feel the need of security. Thus, in the state of happiness, we have no positive forward-looking desires. In a sense there is nothing left 33 Vat. XXXIII. LM 1, 2 (L&S 21 B). 35 See DRN III, 935-939. 36 Beside the two fragments quoted above, there are many others which stress the importance of the sense of confidence and security for the happy life: KD 6, 7, 13, 14, 28; Vat. XXXIV; Plutarch, Against Epicurean happiness 1089D (L&S 21 N). 34 for him to do, nothing more to seek, as Epicurus says37. What remains is perhaps a negative desire to avoid pain in the future (or, if we press the doctrine of the disappearance of desire, we still have a reason to avoid pain), but that is also satisfied. It seems to me that desires different from the immediate desires for things pertaining to the body can be satisfied by expectation38. A wise man is confident, that he cannot fall into a very bad state; indeed he might be confident that he shall preserve happiness as long as he lives. He knows that pain is easy to bear, he has friends, and even in severe pain he cannot loose pleasant memories and the soothing rational expectation that the pain will end soon. The memory is a particularly important factor in providing security, for it contains goods one cannot loose. To sum up, by means of sympathetic identification, the Epicurean is always in possession of his past and, to some extent, of his future, and thus he lives a unified and complete life. If in the state of happiness he does not feel any urge or need, this does not take away his capacity to act prudently to avoid pain in the future, and to benefit his friends. Indeed, the habitual concern for friends might be the strongest reason for the Epicurean to go on living. The negative nature of basic natural desires explains thus why the duration of life is irrelevant. If one’s desire to remove pain and fear is satisfied, one does not desire anything more, including the prolongation of life. This does not mean that the telos of life is purely negative. That is not true – the goal of life is to satisfy one’s natural desires. But having this rational goal does not amount to having a further desire or need, which could be frustrated by death. In its attitude to time, Epicureanism turns out to be, in Parfitian terms, a sort of Critical Present-Aim Theory. In admitting of some natural forward-looking desires about the future, it allows us to be concerned about the future in a way not so different from the way we ordinarily care about it. Yet the focus on the perspective from within every particular time makes it possible to dispel both fear of death and excessive attachment to life. The emerging picture of the liberated, happy Epicurean which I have tried to sketch seems at last understandable and not without attraction. Bibliography The quotations from LM are given according to Long and Sedley’s translation (unless stated otherwise). For KD, Vat., and other fragments I have used Bailey’s translation in J. Gaskin (ed.), The Epicurean Philosophers, Everyman 1995. Glannon W., Epicureanism and Death, The Monist, 76 (1993), 222-234 Kamm F. M., Morality, Mortality, vol. I: Death and Whom to Save from It, New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press 1993 Nagel T., Death, in: Mortal Questions, Cambridge University Press 1979 Nussbaum M. C., Mortal Immortals: Lucretius on Death and the Voice of Nature, 37 Cf. also DRN III, 945-946. If somebody would object to such usage, I could simply say that the expectation of the satisfaction of forward-looking desires is all that really matters to us at any given time. 38 Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 50 (1989), 303-351 Parfit D., Reasons and Persons, Oxford University Press 1984 Rosenbaum S. E., Epicurus and Annihilation, Philosophical Quarterly, 39 (1989), 81-90 Rosenbaum S. E., Epicurus on Pleasure and the Complete Life, The Monist, 73 (1990), 21-41 Rosenbaum S. E., The Symmetry Argument: Lucretius against the Fear of Death, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 50 (1989), 353-373 Warren J., Facing Death. Epicurus and His Critics, Oxford University Press 2004, chp. 2 and 3 Williams B., The Makropulos Case: Reflections on the Tedium of Immortality, in: Problems of the Self: Philosophical Papers 1956-1972, Cambridge University Press 1973