Federist paper madison vs hamilton copy

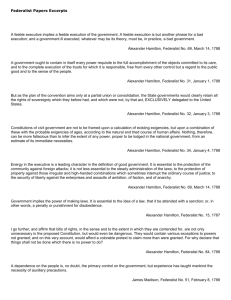

advertisement

Jefferson Quotes “It would reduce the whole instrument to a single phrase, that of instituting a Congress with power to do whatever would be for the good of the United States; and as they would be the sole judges of the good or evil, it would be also a power to do whatever evil they please. Certainly no such universal power was meant to be given them. It [the Constitution] was intended to lace them up straightly within the enumerated powers and those without which, as means, these powers could not be carried into effect.” Thomas Jefferson, Opinion on a National Bank, February 15, 1791 Who wrote it? What is it saying? Why did they write it? What is the point of it? When was it written? Where was it written? What was happen when it was written? “Although a republican government is slow to move, yet when once in motion, its momentum becomes irresistible.” Thomas Jefferson, letter to Francis C. Gray, 1815 “Every government degenerates when trusted to the rulers of the people alone. The people themselves, therefore, are its only safe depositories.” Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, Query 14, 1781 “I consider the foundation of the Constitution as laid on this ground that 'all powers not delegated to the United States, by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states or to the people.' To take a single step beyond the boundaries thus specially drawn around the powers of Congress, is to take possession of a boundless field of power, not longer susceptible of any definition.” Thomas Jefferson, Opinion on the Constitutionality of a National Bank, February 15, 1791 “I know no safe depository of the ultimate powers of the society but the people themselves; and if we think them not enlightened enough to exercise their control with a wholesome discretion, the remedy is not to take it from them, but to inform their discretion by education. This is the true corrective of abuses of constitutional power.” Thomas Jefferson, letter to William Charles Jarvis, September 28, 1820 Hamilton and Madison Quotes A feeble executive implies a feeble execution of the government. A feeble execution is but another phrase for a bad execution; and a government ill executed, whatever may be its theory, must be, in practice, a bad government. Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 70, 1788 A government ought to contain in itself every power requisite to the full accomplishment of the objects committed to its care, and to the complete execution of the trusts for which it is responsible, free from every other control but a regard to the public good and to the sense of the people. Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 31, January 1, 1788 And it proves, in the last place, that liberty can have nothing to fear from the judiciary alone, but would have everything to fear from its union with either of the other departments. Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 78, 1788 Nothing, therefore, can be more fallacious than to infer the extent of any power, proper to be lodged in the national government, from an estimate of its immediate necessities. Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 34, January 4, 1788 Good constitutions are formed upon a comparison of the liberty of the individual with the strength of government: If the tone of either be too high, the other will be weakened too much. It is the happiest possible mode of conciliating these objects, to institute one branch peculiarly endowed with sensibility, another with knowledge and firmness. Through the opposition and mutual control of these bodies, the government will reach, in its regular operations, the perfect balance between liberty and power. Alexander Hamilton, speech to the New York Ratifying Convention, June 25, 1788 I am persuaded that a firm union is as necessary to perpetuate our liberties as it is to make us respectable; and experience will probably prove that the National Government will be as natural a guardian of our freedom as the State Legislatures. Alexander Hamilton, speech to the New York Ratifying Convention, June, 1788 I go further, and affirm that bills of rights, in the sense and to the extent in which they are contended for, are not only unnecessary in the proposed Constitution, but would even be dangerous. They would contain various exceptions to powers not granted; and on this very account, would afford a colorable pretext to claim more than were granted. For why declare that things shall not be done which there is no power to do? Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 84, 1788 If the federal government should overpass the just bounds of its authority and make a tyrannical use of its powers, the people, whose creature it is, must appeal to the standard they have formed, and take such measures to redress the injury done to the Constitution as the exigency may suggest and prudence justify. Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 33, January 3, 1788 The fabric of American empire ought to rest on the solid basis of THE CONSENT OF THE PEOPLE. The streams of national power ought to flow from that pure, original fountain of all legitimate authority. Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 22, December 14, 1787 [T]he Constitution ought to be the standard of construction for the laws, and that wherever there is an evident opposition, the laws ought to give place to the Constitution. But this doctrine is not deducible from any circumstance peculiar to the plan of convention, but from the general theory of a limited Constitution. Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 81, 1788 No government, any more than an individual, will long be respected without being truly respectable; nor be truly respectable without possessing a certain portion of order and stability. Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 62, 1788 By what is government itself but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place, oblige it to control itself. A dependence on the people is no doubt the primary control on the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions. Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 51, 1788 The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many, and whether hereditary, self-appointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny. Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 47, 1788 The want of a mutual guarenty of the state governments is another capital imperfection in the federalist plan. There is nothing of this kind declared in the articles that compose it; and to imply a tacit guaranty from considerations of utility, would be a still more flagrant departure from the clause which has been mentioned, than to imply a tacit power of coercion from the like considerations. The want of a guaranty, though it might in its consequences endanger the Union, does not so immediately attack its existence as the want of a constitutional sanction to its laws. Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 21, 1788 If we resort for a criterion to the different principles on which different forms of government are established, we may define a republic to be, or at least may bestow that name on, a government which derives all its powers directly or indirectly form the great body of the people and is administered by persons holding their offices during pleasure, for a limited period, or during good behavior. It is essential to such government that it be derived from the great body of the society, not from an inconsiderable proportion, or a favored class of it; otherwise a handful of tyrannical nobles, exercising their oppression by a delegation of their powers, might aspire to the rank of republicans, and claim for their government the honorable title of republic. James Madison, Federalist Papers # 39 It is sufficient for such a government that the persons administering it be appointed, either directly or indirectly, by the people; and that they hold their appointments by either of the tenures specified; otherwise every government in the United States …would be degraded from the republican character. James Madison, Federalist Papers # 39 According to all the constitutions… the tenure of the highest offices is extended to a definite period, and in many instances, both within the legislative and executive departments, to a period of years. According to the provisions of most of the constitutions, again, as well as according to the most respectable and received opinions on the subject, the members of the judiciary department are to retain their offices by the firm tenure of good behavior. James Madison, Federalist Papers # 39 The proposed Constitution, therefore, is, in strictness, neither a national nor a federal constitution, but a composition of both. In its foundation it is federal, not national; in the sources from which the ordinary powers of the government are drawn, it is partly federal and partly national; in the operation of these powers it is national, not federal; in the extent of them, again, it is federal, not national and finally in the authoritative mode of introducing amendments, it is neither wholly federal nor wholly national. James Madison, Federalist Papers # 39 The constitution proposed by the convention may be considered under two general points of view. The first relates to the sum or quantity of power which it vests in the government, including the restraints imposed on the states. The second, to the particular structure of the government and the distribution of this power among its several branches. James Madison, Federalist Papers # 41 Under the first view of the subject, two important questions arise: 1. Whether any part of the powers transferred to the general government be unnecessary or improper? 2. Whether the entire mass of them be dangerous to the portion of jurisdiction left in the states? James Madison, Federalist Papers # 41 It cannot have escaped those who have attended with candor to the arguments employed against the extensive powers of the government, that the authors of them have very little considered how far these powers were necessary means of attaining a necessary end. James Madison, Federalist Papers # 41