the impact of women's participation in local councils on gender rel

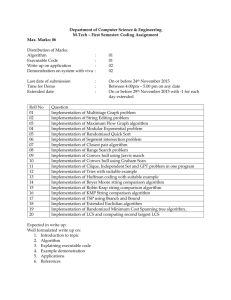

advertisement