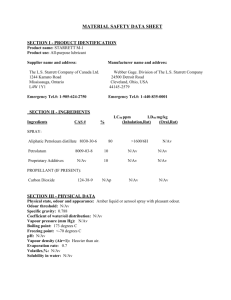

Course Materials

advertisement