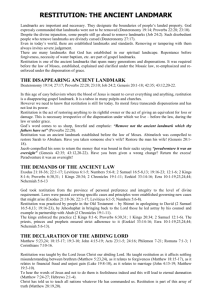

Chapter 6[1] MONITORING AND ENFORCEMENT OF

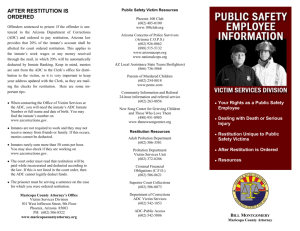

advertisement

![Chapter 6[1] MONITORING AND ENFORCEMENT OF](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008511292_1-6842c077d70f0c501c01cf76788bcced-768x994.png)