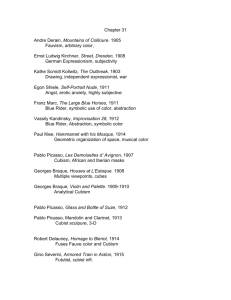

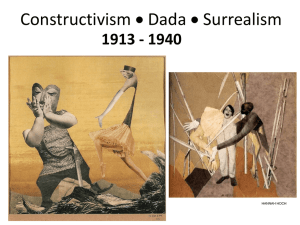

European avant-gardes 1900-1939 vendredi 15 février 2008 22:58

advertisement