doc - Trademark Law: An Open

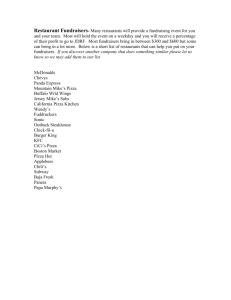

advertisement