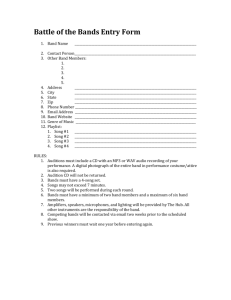

Brats in Babylon

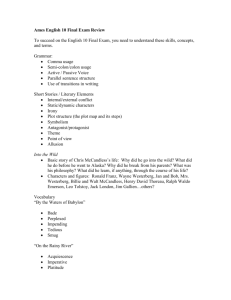

advertisement