the first thanksgiving (1621) – a three day* feast

advertisement

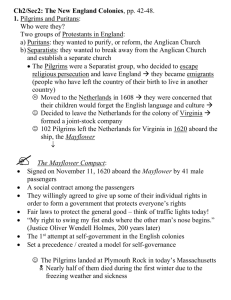

THE FIRST THANKSGIVING (1621) – A THREE DAY* FEAST (*As it turns out, our habit of stretching Thanksgiving by eating leftovers for days – is historically correct) The first Thanksgiving was held one year after the Mayflower Pilgrims landed on Plymouth Rock in 1620. It was basically a thanksgiving for their survival (half the 102 Pilgrims died the first winter), and friendship with the Indians, namely the Wampanoag tribe and their chief, Massasoit, who protected them and gave them peace. And Squanto, an Indian who walked into the Pilgrim’s small settlement speaking English! Squanto taught the Pilgrims how to provide for themselves in fishing and hunting – and most important, how to grow corn – the wheat seeds the settlers brought with them from England, yielded nothing. The Pilgrims were well aware that earlier English settlers were not so fortunate: The “Lost Colony” (1587), sponsored by Sir Walter Raleigh on Roanoke Island (now North Carolina), of 114 men, women and children, completely disappeared (probably due to Indians) by 1590; only the word “CRO” carved in a tree was left at the site of the colony (the mystery was never solved – see below.) Further, of the 214 English settlers of the first permanent English settlement, Jamestown (1607), only 60 survived by 1609. The remainder would probably have died fighting the Indian Algonquin tribe, had John Rolfe not married Pocahontas, daughter of Algonquin chief, Powhatan. (See Rolfe in Bermuda shipwreck, below) Therefore, despite the hardships in the New World, the Pilgrims believed they had reason to be thankful: a bountiful harvest in the fall of 1621 and a peaceful environment to enjoy religious and secular freedoms--both due to positive relations with their new Native American neighbors. The future looked bright. 143 at the First Thanksgiving. The 53 surviving Pilgrims and their guests, 90 Indians of the Wampanoag tribe, sat down to a 3-day feast in the fall of 1621. The exact date is unknown, but historians have narrowed it to between September 21 and November 9, 1621. While George Washington issued a Proclamation for a day of Thanksgiving (November 26) in 1789, it did not become an annual, official holiday in the U.S. until Abraham Lincoln signed the Thanksgiving Proclamation in 1863, which provided for the last Thursday in November. President Roosevelt wanted the next-to-last Thursday, but compromised with Congress which changed it, in 1941, to the fourth Thursday in November, where it is today. The sequence of events leading to that joint feast with the Indians is fascinating---particularly why Squanto, and another Indian, Samoset, spoke English (see below) - and the Peace Treaty, with a mutual assistance clause, the Pilgrims signed with Massasoit. The Wampanoags had enemies among some aggressive, warlike tribes in New England. The alliance was mutually beneficial because the Wampanoags had numbers and knowledge of the territory, and the Pilgrims had muskets. The peace lasted for forty years, until Massasoit died in 1661. The documentation of the first Thanksgiving, and Pilgrim and Indian food, comes from 3 written accounts: Edward Winslow, one of the Mayflower Pilgrims, described it shortly after the event in a letter dated December 12, 1621; the William Hilton letter of November 1621; and Pilgrim Governor William Bradford’s book,“Of Plimouth Plantation” (17th century spelling) written twenty years later. (Original letters at: www.pilgrimhall.org/1stthnks.htm ) Winslow writes: the Indians brought “five Deere”, and that Bradford dispatched 4 men to hunt “fowle”, (the Pilgrims habitually hunted wild turkey, partridge, ducks and geese). Bradford account: “great store of wild turkies” - and from Hilton’s letter: “great flocks of turkey, quails, pigeons and partridges.” Also mentioned: “cod, bass and other fish”; “walnuts, chestnuts, small nuts and plums”; “gooseberries and strawberries”; “Indian corn” (cornbread); “fruits, as vines of divers sorts” (namely cranberries—a favorite of both the Pilgrims and Indians.) Though not specifically mentioned, we can assume that – to feed 143 people for 3 days - other food items in the Pilgrim’s diet were served including: local shellfish (clams, lobsters, mussels, oysters), pumpkins, maple syrup and honey. They did not have sweet potatoes, but pumpkins were plentiful, and the Pilgrims made a pumpkin pudding sweetened by honey or syrup, (though no crispy pie crust or whipped topping). Today, we also have some things to be thankful for---beyond pie crusts and topping---we have a few comforts not available in 1621. Also, many of us will not have to feed 143 people – and dine outside! And our guests may bring a bottle of wine rather than 5 deer. Happy Thanksgiving! LC 2010 A few additional details: Why did Squanto speak English? Squanto, a Patuxet which belonged to the Wampanoag confederation of tribes, was actually preceded in entering the Pilgrims settlement, by Samoset, who spoke broken English. Samoset left to get Squanto who was nearly fluent in English. Squanto had been captured by a rogue subordinate of Capt John Smith, Thomas Hunt, whom Smith had left behind (after Smith’s 1614 mapping expedition) to trade with the Indians. Hunt lured 24 Indians, including Squanto, aboard his ship and took them captive and sailed to Malaga, Spain, to sell them into slavery – but they were freed by local Friars. (Hunt was severely chastised by English authorities and by Smith – the same John Smith saved by Pocahantas). Squanto made his way to England and lived with John Slaney and family in London, where he learned English. Slaney was Treasurer of the Newfoundland Company and sent Squanto to their Newfoundland colony as an interpreter and expert on North American resources. Principals of the Newfoundland Company wanted to trade with Indians in Massachusetts, and travels there eventually brought Squanto into contact with the Pilgrims. Squanto stayed with the Pilgrims for a few months teaching them survival skills. He taught them how to cultivate corn, beans, and other vegetables. Squanto taught the pilgrims to bury three fish and then plant the corn on top of the fish. The fish served as fertilizer. He taught them to plant beans around the corn to allow the bean plants to climb up the corn stalks for better growing. Squanto taught the Pilgrims about poisonous and medical plants, demonstrated how to dig for clams, get sap from maple trees, trap beaver, and many other skills. Wampanoag Chief Massasoit: Pilgrims choose Edward Winslow Mutual Assistance Treaty for 1st meeting with Massasoit Engraving – Library of Congress Statue of Massasoit Facing Plymouth Harbour Why was Massasoit, interested in the Mutual Assistance Treaty with the Pilgrims? Massasoit was sachem (chief) of the Wampanoags, a group of people who had lost many people from a devastating epidemic from 1616 to 1618. This put them in a weakened position with other Native tribes, so Massasoit found an ally in the Pilgrims who also needed protection. Or rather, they found each other. After Massasoit died in 1661 relations between the two became very rocky. But that does not detract from this remarkable treaty, in 1621, between two peoples from different worlds – and the equally remarkable Thanksgiving dinner. Massasoit statue on grounds of Utah State Capitol The First Thanksgiving. As you might imagine, when cooking for 143 people in 1621, the meal was not prepared with individualized cooking. There was no “I’ll have my venison, medium well” etc. There was no cabernet reduction. However, both the English and the native Americans knew how to cook for large numbers, and the food was very tasty. There were no forks at the time - just knives and spoons, and plates were primarily wooden. Where are the Wampanoag’s today? The current Wampanoag tribe headquarters has a very attractive location on Martha’s Vineyard. LMC & PKC were unaware of the historic importance of the Wampanoag’s to Thanksgiving and development of our country, when, after a golf outing there in August 2002, we drove through the Wampanoag property. In addition to the HQ building, we noticed several shiny new vehicles in the parking lot with the Wampanoag logo. Wonder if they still get together with Mayflower descendants on Thanksgiving? Who were the Pilgrims? The Pilgrims were English Separatists, also known as “Puritans”, which separated from the Church of England because they felt it had not completed the work of the Reformation. Some moved to Leiden, Holland, where they felt they had more religious freedom. After several years, many of the Leiden and English Puritans wished to emigrate to the New World. 37 of the Leiden congregation sailed for London on the 60 ton Speedwell to join the English Puritans who had contracted for transportation aboard the 180 ton Mayflower, a 3-masted merchant vessel originally constructed to transport wine. On August 15, 1620, the two vessels sailed from Southampton, but they were twice forced back by dangerous leaks on the Speedwell. At the English port of Plymouth, some of the Speedwell's passengers were regrouped on the Mayflower, and on September 16, with a final head-count of 102, the historic voyage began. The voyage took 65 days during which two people died, and two were born. Who were the non-Separatists on the Mayflower? The non-Separatists were Christopher Jones, Mayflower Captain and part-owner, and his crew of 30— including John Alden, a cooper, who stayed in Plymouth with the Pilgrims - and married Priscilla Mullins (“Speak for yourself, John” from the famous poem, “The Courtship of Miles Standish” by Longfellow--Longfellow was a direct descendant of John and Priscilla.) Also, the Pilgrim’s hired help: among them Myles Standish, a professional soldier, Peter Browne, a carpenter and Stephen Hopkins, believed to be a soldier---and other colonists who were to be taken along at the insistence of the London businessmen who were helping to finance the expedition – in hopes of making a profit from the future colony. What was the “Mayflower Compact”? The original land grant from the London Company for the Pilgrims was in the area of the mouth of the Hudson River – then in the Virginia Colony. However, they first dropped anchor near what is now Provincetown, Cape Cod, on November 21. The Separatists were concerned that the non-Separatists would object to settling on land other than the land grant – and therefore, to make it legal, on November 21, 41 men (including the non-Separatists) signed the Mayflower Compact, a “Civic Body Politic” (temporary government), and agreed to be bound by its laws in their future American colony. The Mayflower then raised anchor and after weeks of scouting for a suitable settlement location, entered Plymouth harbor and landed on December 26, 1620. It was named “Plymouth” earlier by John Smith after the port of Plymouth, England – Smith also named “New England.”. There they established the Plymouth Colony. Captain Jones kept the Mayflower anchored at Plymouth during the harsh winter, and many of the Pilgrims stayed aboard and many died from exposure, scurvy and contagious disease. The Mayflower left Plymouth on Apr. 15, 1621, arriving back in England on May 16. What happened to Sir Walter Raleigh’s “Lost Colony”? After settling the colony in 1587, the leader of the Roanoke Colony, John White (grandfather of Virginia Dare, the first European born in New World), returned to England for supplies. His return was delayed by war with Spain for 3 years. When he arrived at the Colony in August 1590, he found all personal belongings in place but the people had completely disappeared. Finding a word “CRO” carved in a tree which he speculated might be an abbreviation for Croatoan, a nearby island, he sailed to Croatoan, but did not find a trace. Two solutions to the mystery have been proposed: (1) the entire Colony was massacred by Indians; (2) the population assimilated into local tribes---either voluntarily in order to have food to eat, or involuntarily, e.g. part of whites were killed (men?) and others were captured and forced to live with tribes. In 1709 (119 years later) an English explorer, John Lawson, visited the Hatteras Indian tribe in the area and wrote, “several of their ancestors were white people who could talk in a book as we do, and had gray eyes.” In the 1880's (300 years later) it was noted that an Indian tribe in southeastern North Carolina, the Pembroke Indians, claimed that their ancestors were from "Roanoke in Virginia". Some of the tribe members bore the same last names as some of the missing colonists. In addition, many members of the tribe had Anglo features - fair eyes, light hair, and Anglo bone structure. http://www.spartechsoftware.com/dimensions/vanished/LostColony.htm#Mystery In any event, knowing the history of Roanoke Colony, and that the Jamestown Colony lost nearly ¾ of the people in two years, the Pilgrims in Massachusetts felt they had much to be thankful for. Another colonist hardship preceding the Pilgrims: English colonists headed for Jamestown in 1609---their ship wrecks off Bermuda. Results in founding of Bermuda (1609), and basis for Shakespeare’s The Tempest – first performed two years later in London (1611). On July 2, 1609, the Sea Venture, the new Flagship of the Virginia Company, and 8 other vessels in the fleet carrying 500 - 600 people, set sail from Plymouth, England, for Jamestown. On July 24, the fleet was hit by a storm (likely a hurricane) and the ships were separated. With the Sea Venture severely damaged by the storm and leaking badly - with nine feet of water in the hold - the captain, on July 25, after spying land, ran her aground on the reefs of Bermuda to prevent the ship from foundering. (This storm was the inspiration for Shakespeare’s The Tempest - see .) Among the passengers were Admiral Sir George Somers, Sir Thomas Gates—Virginia’s first Governor-Designate, and John Rolfe. All 150 people, and one dog, on board made it ashore safely, but in the next 9 months some died (like John Rolfe’s wife and daughter) and some were born. Bermuda was an uninhabited island – named for Juan de Bermudez, Spanish navigator who first discovered it in 1503---but, there were wild hogs (which likely survived earlier Spanish, Portuguese, French and British shipwrecks on the Bermuda reefs), “turtles, fish and fowle”, and Bermuda cahows which provided much of the food for the Sea Venture survivors. In those 9 months, under the direction of Admiral Somers, the survivors built two vessels, Deliverance and Patience, from parts of the Sea Venture (including the indispensable riggings) and indigenous Bermuda cedar wood, and on May 10, 1610, set sail for Jamestown, arriving on May 23, 1610. On November 1, 1611, in London, England, at Whitehall, for King James VI of Scotland and I of England, the first performance was presented of the original dramatic and musical work, “THE TEMPEST”, by the British dramatist and playwright William Shakespeare, with music by the British composer Robert Johnson. The drama was based on true accounts by English writer, historian and lawyer William Strachey, of Lyme Regis, Dorset, England, and Sylvester Jourdain. Both had been in the Bermuda shipwreck before they got to Jamestown, Virginia, and ultimately returned to England. Whole sections of the original text were taken by Shakespeare from their dramatic accounts and the surprising survival of Gates and Somers, whom all of London had presumed drowned. But, as a work of fiction, Shakespeare changed some of the names and the island became a mythical Italian island. http://shakespeareauthorship.com/tempest.html _________ George Washington's 1789 Thanksgiving Proclamation (as published in Mass. Centinel) "I do recommend and assign Thursday, the 26th day of November next, to be devoted by the people of these States to the service of that great and glorious Being who is the beneficent author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be; that we may then all unite in rendering unto Him our sincere and humble thanks for His kind care and protection of the people of this country… “