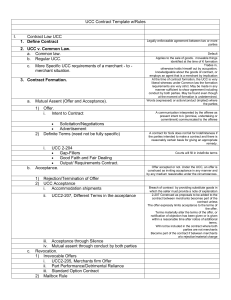

I. K Contract Formation in the Form Contract Setting & UCC 2-207

A. 2 Questions to Ask:

1. Was a K formed?

2. If so, what terms govern?

B. Common Law: Mirror image rule! No K formed if offer & acceptance are not mirror images!

Not practical so use UCC 2-207

C. Form K’s create problems of conflicting terms. To Avoid:

1. Don’t bury favored terms in boiler-plate clauses; make acceptance conditional;

communicated w/ other party to ensure forms have identical terms/meanings; have

other party sign specific clause in overall agreement; return to old school or having K

signed by both parties w/ mutually agreed to terms.

D. UCC 2-207:

1. A definite and seasonable expression of acceptance OR a written confirmation

which is sent w/in a reasonable time operates as an acceptance even though it

states terms additional to or different from those offered or agreed upon, UNLESS

acceptance is expressly made conditional on assent to the additional or different

terms.

2. The additional terms are to be construed as proposals for addition to the contract.

Between merchants such terms become part of the contract UNLESS:

a) The offer expressly limits acceptance to the terms of the offer;

b) They materially alter it;

(1) A proposed alternation in an acceptance is material and does not enter

the K if it would result in surprise or hardship to the other party

c) Notification of objection to them has already been given or is given w/in a

reasonable time after notice of them is received.

(1) Note: 2-207(2) require that the transaction be b/w merchants and both

must be merchants, and if either is not a merchant, end the matter.

3. Conduct by both parties, which recognizes the existence of a contract is sufficient to

establish a contract for sale although the writings of the parties do not otherwise

establish a contract. In such case the terms of the particular contract consist of those

terms on which the writings of the parties agree, together w/ any supplementary

terms incorporated under any other provisions of this Act.

a) Gap Fillers: (unless the parties otherwise agree)

(1) 2-308 states that delivery must takes place at the seller’s premises

(2) 2-310 requires payment n delivery

(3) 2-314, 2-315 provide for minimum warranties

b) Under 2-207(3) a K is recognized on the terms on which the writings agree

(description, quantity, price, delivery, and payment) and the other stuff falls

out

(1) See HYPO – price of tractor, delivery, etc remains if agreed to and

arbitration clause will fall out.

E. UCC 2-207:

1. Material Alteration (P. 498)

a) Comment 4. Material Alteration Examples (causes surprise or hardship)

(1) A clause negating such standard warranties as that of merchantability

or fitness for a particular purpose in circumstances in which either

warranty normally attaches

(2) A clause requiring a guaranty of 90% or 100% deliveries in a case

such as a K by cannery, where the usage of the trade allows greater

quantity leeway

1

2.

3.

4.

5.

(3) A clause reserving to the seller the power to cancel upon the buyer’s

failure to meet any invoice when due

(4) A clause requiring that complaints be made in a time materially shorted

than customary or reasonable

b) Comment 5. Non-Material Alterations (where no element of surprise or

hardship and which therefore are incorporated into K unless notice of

objection is seasonably given)

(1) A clause setting forth and perhaps enlarging slightly upon the seller’s

exemption due to supervening causes beyond his control, similar to

those covered by UCC on merchant’s excuse by failure to

presupposed conditions or a clause fixing in advance any reasonable

formula of proration under circumstances

(2) A clause fixing a reasonable time for complaints w/in customary limits

or in the case of a purchase for sub-sale, providing for inspection by

the pub-purchaser

(3) A clause providing for interest on overdue invoices or fixing the seller’s

standard credit terms where they are w/in the range of trade practices

and do not limit any credit bargained for

(4) A clause limiting the right of rejection for defects which fall w/in the

customary trade tolerances of acceptance “w/ adjustments” or

otherwise limiting remedy in a reasonable manner (see also 2-718 –

liquidating damages and 2-719 – K modification)

Additional Term: if it adds new matter not covered in the offer

Different Term: if it varies or contradicts something provided for in the offer

Are additional terms a part of the agreement?

a) Comment 6:

(1) If no answer is received w/in a reasonable time after additional terms

proposed, it is both fair and commercially sound to assume that their

inclusion has been assented to.

(2) In the event that there are clauses that conflict on form sent by both

parties, they are construed as being in objection to each other and the

requirement of notice in subsection (2) is not satisfied and thus the

terms do not become part of the K.

(3) The K then consists of the terms originally expressly agreed to, terms

on which the confirmations agree, and terms supplied by this Act,

including subsection (2).

“Additional” versus “Different”:

a) If additional terms NOT made conditional on acceptance, under 2-207(2),

terms will be considered proposals for addition to the K UNLESS, see (2)(a,

b, and c).

b) If additional terms made conditional on acceptance, and there was no

express acceptance of these terms, then go to 2-207(3) and the K is

governed by the terms on which the 2 writings agree. Then go to UCC as a

“gap filler” (2-305 and 2-311)

c) If different terms, various rules apply:

(1) Knock-out Rule (White): Conflicting terms cancel each other out

under Comment 6 and K consists of terms to which both writings

agree. Once conflicting terms are knocked out, go to UCC as gap

filler.

2

(a) Policy: preserving a K and filling in any gaps is the purpose of

the UCC; protects offeree since neither term would govern and

the UCC would fill in an appropriate term

(2) First-Shot Rule (Summers): Different terms just fall out (unless

offeree expressly objects to the original term) and original term applies.

(a) Policy: Offeror is the master of the offer: while this rule may give

offeror an advantage, Summers argues such advantage is not

unearned – offeror’s have slightly more reason to expect that

their clauses will control than offerees

(3) Roto Lith Rule: any responding document which states a condition that

MATERIALLY ALTERS the obligation SOLELY TO THE

DISADVANTAGE of the offeror is expressly conditional and thus does

not operate as acceptance

(a) Note: Summers/White disagree w/ Roto-Lith b/c it is inconsistent

w/ the word “acceptance” in 2-207(1) and contrary to the

drafter’s policy to whittle down the counteroffer rule

F. Cases:

1. Daitom, Inc. v. Pennwalt Corp. (pg. 503): (different term case)

a) Seller’s doc. sent PO, including a 1 yr SOL period; Buyer’s doc. Suggests the

PO carries remedies implied by or available at law (usually 4 yrs). Issues: Is

there a K? Does the 1 yr SOL period become part of the K? Holding: the

terms are not additional – they are different, so subsection (2) does not apply;

thus, using Knock-out rule, the terms cancel out, and pull in the UCC’s 4 yr

SOL; UCC provides the gap filler

b) Rule: White’s approach: Knock-out Rule

2. ProCD v. Zeidenberg (pg. 515)

a) Rule: terms inside a box of software bind consumers who use the software

after an opportunity to read the terms and to reject them by returning the

product; only terms known to the consumer at the moment the K is formed

are part of the K and provisos inside the box do not count (in Hill, the warranty

terms were distributed at time of K)

3. Hill v. Gateway 2000 (pg. 515): (no exchange of forms)

a) H bought computer that had arbitration clause in terms; H kept computer

more than 30 days and brought suit; Gateway tried to enforce clause;

Holding: by keeping computer beyond 30 days, Hills accepted Gateway’s

arbitration clause

b) Rule: ProCD rule

c) NOTE: this was not a traditional battle of the forms case since a phone convo

is not really a “form” but then again, 2-207 applies when the parties’ conduct

indicates that a K has been formed but fail to adopt expressly a particular

writing so unclear

4. Step-Saver Data Systems v. Wyse Tech., Inc. (pg. 518): (additional term case)

a) Facts: S-S bought computer software from Wyse and brought suit for breach

of warranty when software developed problems; Issue: do the disclaimer of

warranties and limitation of remedies printed on the package containing

software = terms of agreement? Holding: S-S never expressly agreed to

terms of the box-top license, and the terms should be treated as additional

terms; since they would materially alter, they don’t become a part of the

agreement

b) Rule: 2-207(2)(b) governs

3

c) Note: Also may have been found to fall out under 2-207(3) as buyer had

already paid for software and tried to use it.

G. HYPO: buyer send PO for tractor that says any dispute will be resolved by arbitration.

Seller responds w/ acknowledgment that says no arbitration. All other terms are agreed to

(Price, delivery, quantity, etc.)

1. Under CL – no K under mirror image rule

2. Under 2-207 if the bargained terms on PO and acknowledgment agree K

3. Is seller’s acknowledgment a confirmation based on an oral K or is it an acceptance

in reply to an offer

a) An acceptance

4. What result under Roth-Lith Rule?

a) Rule: a condition, which materially alters the obligation solely to the

disadvantage of the offeror, is expressly conditional and doesn’t operate as

an acceptance.

b) Did it materially alter?

(1) Buyer would argue yes – extra costs, different rules of evidence, etc

(2) Seller would argue No – it is ancillary/incidental term of overall K

c) Was it solely to disadvantage of offeror?

(1) No – buyer may wish to take advantage of ct system at times

(2) Yes – buyer wants an arbitration clause and seller does not

d) Note that Roth-Lith no longer applies in most jdx

5. If Roth-Lith doesn’t apply, acceptance is not conditional; Buyer asks seller to ship

and seller doesn’t. Can buyer sue for breach of K?

a) Yes – K exists under 2-207(1)

b) Does the buyer the arbitrate or go to ct?

(1) Is 2-207(2) invoked? Determine if additional or different term.

(a) Most likely different terms as it conflicts in both party’s writings.

(b) 2-207(2) only apply to additional terms.

(i) Minority opinion says different terms are included here,

but this is not majority rule.

(c) 2-207(3) points out that only terms where writings agree are

terms of K. So buyer can go to ct as arbitration clause falls out

under Knock-Out Rule (White - conflicting terms cancel each

other out).

(d) First-Shot Rule

6. What is tractor was shipped, if there a K under CL?

a) Yes – seller making acceptance w/ different terms is seem as counter-offer

b) By making payment and taking delivery, buyer has accepted to the no

arbitration clause.

7. What if buyer didn’t have arbitration clause, and sell still had no arbitration clause?

a) Then 2-207(2) would be invoked as it is an additional term

(1) Check to see if meets the sections unless factors

b) What if the buyer goes ahead and pay and the tractor is shipped

(1) Then 2-207(3) applies and conflicting terms fall out

(a) Additional term then not arbitration clause would not be in K

4

II. Policing Doctrines (defenses where there is grossly unfair terms or overreaching by one party at

the bargaining or promising stage (or both)

A. Duress

1. Elements of Duress: (from reasonable person standard)

a) Must be a threat

b) Threat must be improper (RST 176)

c) Threat must induce victim’s manifestation of assent

d) No reasonable alternative

2. Note: a threat to refuse performance of a K cannot be made the predicate of legal

duress (Cable v. Foley, pg. 527)

3. Rules:

a) RST 176: When a Threat is Improper

(1) A threat is improper if

(a) What is threatened is a crime or a tort, or the threat itself would

be a crime or tort if it resulted in obtaining property,

(b) What is threatened is a criminal prosecution,

(c) What is threatened is the use of civil process and the threat is

made in bad faith, or

(d) The threat is a breach of the duty of good faith and fair

dealing under a K w/ the recipient.

(2) A threat is improper if the resulting exchange is not on fair terms,

AND

(a) The threatened act would harm the recipient and would not

significantly benefit the party making the threat

(b) The effectiveness of the threat in inducing the manifestation of

assent is significantly increased by prior unfair dealing by the

party making the threat, or

(c) What is threatened is otherwise a use of power for illegitimate

ends

b) Standard Box: In cases of alleged duress to make a payment:

(1) There must be some compulsion or coercion, some threatened

exercise of power or authority over his person or property, which can

be avoided only by making the payment.

(2) Such payment is not to be regarded as compulsory unless made to

free the person or property from an actual and existing duress imposed

upon it by the party to whom the money is paid.

(3) Mere threat to w/hold from a party a legal right, which he has an

adequate remedy to enforce, is not duress.

c) S.P. Dunham: Has the person complaining of duress been constrained to do

what he otherwise would not have done? (Reasonable person standard)

d) Undue Influence: the pressure must be exerted by a person enjoying a

special relationship w/ the victim that makes the victim especially susceptible

to the pressure.

4. Cases:

a) Standard Box Co. v. Mutual Biscuit Co. (pg. 526) (no duress)

(1) Π box seller offer ∆ option to buy boxes at a certain price. An

earthquake raises prices and ∆ attempts to buy under old pricing, but π

says that option is no longer available. ∆ accepts boxes at mkt price,

refuses to pay later, and π sues. Ct finds that option expired so no K

existed b/w π and ∆. No grounds for duress as π was only charging

mkt price, there was no K b/w parties, and ∆ acted voluntarily.

5

(2) Different result is option K has been accepted and π said it would only

sell as market price

(3) Different result if π raised prices just for ∆ or for everyone in mkt – ct

would look to see if price was excessive or burdensome.

b) S.P. Dunham & Company v. Kudra (pg. 529): (duress)

(1) Π has dept. store w/ area leased to fur restorer who outsources to ∆.

When fur restores went bankrupt, he owed ∆ money and ∆ had

possession of all furs. Π asked ∆ to return furs, but it said it would only

do so if π paid off the debt or it could give ∆ the list of people and it

would return. Ct found that ∆ made improper threat by forcing π to

make K so that it could get furs back to customers ASAP (also dead of

winter)

(2) Under RST 176(1)(a) – could be seen as tort for conversion as they

would keep furs unless π made K

(3) Reasonable Alternative – ct said π should not have to resort to RA and

that there was none in this case

c) Remedies for Duress

(1) Rescission

(2) Restitution

B. Misrepresentation

1. Elements of Misrepresentation:

a) State of mind is irrelevant

(1) Misrepresentation can be innocent, negligent or intentional

b) There must be justifiable reliance by π

(1) Gullible people sometimes protected

c) Must be a misrepresentation of fact

2. RST 552C: Misrepresentation in Sale, Rental or Exchange Transaction

a) One who, in a sale, rental or exchange transaction w/ another, makes a

misrepresentation of a material fact for the purpose of inducing the other to

act or to refrain from acting in reliance upon it, is subject to liability to the

other for pecuniary loss caused to him by his justifiable reliance upon the

misrepresentation, even though it is not made fraudulently or negligently.

b) Damages recoverable are limited to the difference b/w the value of what the

other has parted w/ and the value of what he has received in the transaction.

3. Innocent Misrepresentation:

a) General Rule: a person seasonably (timely) may rescind a K to which he has

been induced to become a party in reliance upon false, although innocent,

misrepresentations respecting a cognizable material fact made as of his own

knowledge by the other party to the K.

(1) Bates v. Cashman (pg. 535): During negotiations, π represented there

was a right of way, a substantial factor affecting purchase by ∆, which

turned out to be false although innocently made; Holding: ∆ can

rescind b/c of π’s false statements (although innocently made).

4. Negligent Misrepresentation:

a) Gibb v. Citicorp Mortgage Inc: ∆ sold house to π w/ an “as is” disclaimer, but

had indicated that termite problem was limited to certain area and had been

fixed. Ct finds disclaimer is not absolute, jury may still find if fraud controlled

bargain. Ct finds that ∆ was liable of negligent misrepresentation. Π did not

have a duty for further investigation.

(1) Misrepresentation can be used as a shield (avoid K) or a sword (retain

K, but make the other party correct the defects).

6

5. Fraudulent Misrepresentation:

a) π must allege and prove:

(1) That a representation was made as a positive assertion;

(2) That the representation was false;

(3) That when made, the representation was known to be false or made

recklessly w/o knowledge of its truth or falsity

(4) That it was made w/ the intention that π should rely on it;

(5) That π reasonably did so rely;

(6) That π suffered damage as a result.

b) Holcomb v. Hoffschneider (pg. 541): ∆ sold π land guaranteeing 6.6 acres,

but it fell short. π sued for misrepresentation and won. Ct said that buyer did

not have to conduct its own survey and could rely on ∆’s assurances.

(1) Factors: π asked ∆ numerous times, ∆ made a specific guarantee, both

walked the property together

(2) Note: Vague statement may not result in misrepresentation as not

reasonable to rely on such statements.

c) Porreco v. Porreco (pg. 544): fake engagement ring; Holding: W’s reliance on

ring’s value was not justifiable

(1) Distinction b/w Porreco and Holcomb: the property did not yet belong

to them; Porreco owned the ring and had possession

6. Misrepresentation and Damages:

a) 3 Categories:

(1) Innocent misrepresentation:

(a) Π can recover restitution damages – usually in sale, exchange,

rental, etc.

(b) Bates indicated rescission also allowed

(2) Negligent misrepresentation:

(a) Π can recover reliance damages – usually limited to

commercial, employment, pecuniary transaction

(3) Fraudulent misrepresentation: (RST 549)

(a) Π can get expectancy damages – usually only in commercial

transactions.

C. Concealment

1. Fraudulent Concealment:

a) π must allege and prove:

(1) That ∆ concealed or suppressed a material fact;

(2) That ∆ had knowledge of this material fact;

(3) That this material fact was not w/in the reasonably diligent attention,

observation, and judgment of π

(4) That ∆ suppressed or concealed this fact w/ the intention that π be

mislead as to the true condition of the property;

(5) That π was reasonably so misled; and

(6) That π suffered damage as a result.

b) General Rule: silence may be fraudulent where, under the circumstances, the

seller is bound in conscious and in duty to disclose to the other party and in

respect, to which he cannot, innocently, be silent. If the fraudulent

concealment is material enough, this may justify rescission of the K

(1) Weintraub v. Krobatsch (pg. 546): (active concealment)

(a) After inspecting home illuminated, ∆ signed contract w/ π, but

before closing, ∆ discovered a REALLY BAD roach infestation

7

and rescinded; π sued for value of the deposit and broker fee; ∆

claimed the π was aware of and concealed infestation

(b) Holding: ∆ can maintain action for fraud

c) “As Is” Clauses: allegations of active concealment trump “as is” clauses: in

order for “as is” clause to be enforced, there must be no allegations of

fraudulent concealment

(1) Gibb v. Citicorp Mortgage, Inc. (pg. 535): ∆ acquires house through

mortgage foreclosure; ∆’s agents informed house is termite infested,

but instead of remedying, they just cover it up; ∆ tells π damage been

repaired and no problem; π purchases property and signs “as is”

clause. π then attempts to rescind based on fraud misrepresentation

and concealment

(a) Holding: As is clause is not a bar to pursuing COA

D. Duty to Disclose

1. Kronman: Mistake, Disclosure, Information and the Law of Contracts

a) “Deliberately acquired information”: info whose acquisition entails costs which

would not have been incurred but for the likelihood that the info in question

would actually be produced (Ex: direct search costs, cost of school)

b) “Casually acquired information”: info that would have been acquired in any

case

c) The distinction b/w the 2 helps to understand when a duty to disclose arises:

(1) Cases requiring disclosure involve info which is likely to have been

casually acquired

(2) Cases permitting nondisclosure involve info which is likely to have

been deliberately produced

d) When looking to see how information was acquired – look at parties intent

e) Thus, disclosure cases give the appearance of promoting allocative efficiency

by limiting the assignment of property rights to those types of information

which are likely to be the fruit of deliberate investment

2. Fried: (p. 550) ct may still require disclosure despite above based on duty of good

faith

E. Public Policy (basic tension w/ this defense is balancing interests in autonomy and public

policy)

1. Cases in which a K is contrary to Public Policy

a) Penalty clauses

b) Unduly retraining of trade or sale of real property

c) Unduly interfere w/ judicial or govt processes

d) K’s made by ppl not properly licensed (Bloomgarden: B didn’t have license to

charge for finder’s fee; Building K’s: if you don’t have a license to build, cant K

for it)

e) Illegal Ks such as K’ing to commit a crime

2. Exculpatory Agreements (Disclaimers)

a) RST 574: a bargained-for exemption from liability for the consequences of

negligence not falling greatly below the standard established by law for the

protection of others against unreasonable risk of harm is legal

(1) McCutcheon v. United States Homes Corp. (pg. 553): (paternalism)

(a) Agreement which exculpates LL in multi-dwelling complex from

liability regarding duty to maintain common areas = void as

against public policy; π injured falling in unlit stairs of ∆’s

apartment complex recovered despite disclaimed in lease. Ct

8

held such disclaimer was contrary to public policy and at CL, ∆

had duty of safety in common areas.

(2) Weaver v. American Oil Co. (pg. 551): lease exculpated American Oil

from liability and required Weaver to indemnify AO for any liability for

AO’s negligence

(a) Conditions for a K to be unenforceable:

(i) It is unconscionable b/c of unequal bargaining power

(ii) It is used to the stronger party’s advantage

(iii) Is unknown to the lesser party

(iv) Causes great risk or hardship on the lesser party

(b) The party seeking to enforce such a K has the burden of

showing that the provisions were explained to the other party

and came to his knowledge and there was a real and voluntary

meeting of the minds and not merely an objective meeting

(3) Kalisch-Jarcho, Inc. v. New York City (pg. 556): exculpatory clause

unenforceable since city acted in bad faith

(4) NOTE: In Weaver, the court invalidated the exculpatory clause partly

b/c American Oil failed to explain it to Weaver, an unsophisticated

contracting party (unconscionable in process). But in Kalisch-Jarcho,

exculpatory clause was unenforceable even though it was b/w two

sophisticated contracting parties b/c of the intentional wrongdoing by

the city (unconscionable in substance).

(5) Molina v. Games Management Services (pg. 557): (disclaimer OK

under public policy) ct honors disclaimer when ∆ sells π winning

lottery ticket, but loses his copy which is required to pay award.

Winning a lottery may not be as important to public policy and ∆ was

only negligent.

3. Contracts Not to Compete/Non-Compete Agreement

a) Arise under 2 situations generally

(1) Sale of business

(2) Employment K’s

b) Questions to Address When Presented w/ Non-Compete Clauses:

(1) Does the agreement even apply at all?

(a) Try to interpret the clause narrowly so that it does not reach

client

(2) Is the party actually injured as a result of the clause?

(3) See if clause can be invalidated based on public need, not behavior of

party

(4) Is the agreement reasonable in time, geography, scope, etc?

(a) Cts want to make sure that clause is not unreasonably broad

(5) If it is unreasonable, what should the court do?

(a) 3 options to deal w/ unreasonable non-compete clauses:

(i) Automatically throw out the whole thing

(ii) Severance: go through the clause and strike out the parts

of the clause making it unreasonable (Karpinski)

(iii) Rewrite agreement to serve intended purpose

(a) This approach has freedom of K issues, but at

least you’re not throwing the whole thing out as in

option (i)

c) Rules

9

(1) General Rule: a non-compete agreement is enforceable if reasonable

as to scope, time, territory and protects legitimate business interests

(a) Karpinski v. Ingrasci (pg. 563): (partial enforcement)

(i) Agreement preventing oral surgeon from practicing

“dentistry” w/in 5-county area forever is unenforceable

since its scope (dentistry) is too broad considering the

party seeking enforcement has legitimate interest in

preventing employee from practicing oral surgery in this

area

(ii) Power to sever – ct could enforce part of the clause

(geographic limitation) and sever unreasonable part

(can’t practice any dentistry)

(2) Quandt’s Wholesale Distributors v. Giardino (pg. 556): (trade secrets)

(a) Agreement only enforceable if reasonably limited temporally and

geographically to extent necessary to protect against

employee’s use/disclosure of trade secrets or confidential

customer list

(b) Ct held that a non-compete clause b/w π employer and ∆ exemployee could not be enforced focusing on the claim of trade

secrets or confidential customer lists. Ct found this info was in

phone book and was readily available (therefore not a secret)

(3) Dwyer v. Jung (pg. 559): (public need)

(a) Ct held that non-compete agreement b/w attorneys could not be

enforced as contrary to public policy. Public should have right to

choose one attorney over the other.

d) Other Examples of K’s Against Public Policy

(1) K Made by mentally handicapped person (RST 15)

(a) Includes senile and drunk people w/ limitations

(2) K made by infant

(a) May ratify after reaching adult age

(b) May be enforced if infant states he is an adult

(3) K to commit crime or tort

(4) K which requires license, but party does not have said license

F. Inequality of the Exchange: Constructive Fraud

1. Doctrine of Constructive Fraud: if a person is in a confidential relationship AND it

turns out that the price paid and the value of the land is so disparate, the court

will find fraud regardless of whether there was an intent to deceive (distinction: intent

to deceive is an essential element for actual fraud but not constructive fraud)

a) Jackson v. Seymour (pg. 571): (constructive fraud)

(1) Ct found that business savvy ∆ who unknowingly purchased π’s land

for $275, but later found out it was worth more for its timber had

committed constructive fraud.

(2) Constructive fraud requires

(a) Confidential relationship

(b) Reliance to one’s detriment

(c) Gross in adequacy in price

(i) Standard – shocks the conscious

(d) Mutual Mistake on the parties

(i) Neither party knew how much the land was worth at the

time

(3) Ct allows rescission of K

10

(a) Π can recover value of timber removed

(b) ∆ can recover price paid ($275) + interest, taxes, expenses, etc.

G. Unconscionability (unethical, unreasonable, undue, unfair, underhanded)

1. Generally

a) If the provision of a K are so grossly unfair as to shocks the conscious of the

ct, judge may decline to enforce the offending terms or the entire K.

2. Approaches

a) Adhesion K’s

(1) General Rule: cts generally do not like to enforce adhesion K’s

(a) Must show that clause is unconscionable or thwarts reasonable

expectations

(2) Policy of Adhesion K’s

(a) Pros

(i) Reduces negotiating time

(ii) Lower cost to K

(iii) Efficiency

(b) Cons

(i) One party can alter K – forcing a take it or leave it

situation

(ii) Nobody reads the fine print on K’s

b) Doctrine of unconscionability

(1) UCC 2-302 (p. 597) (see below)

(a) Decided by ct not jury

(b) Looks to see if unconscionable at time K was made

(c) Latitude in remedy – refuse to enforce K, enforce remainder of

K, limit application by striking clause

(2) Types

(a) Procedural and Substantive (see below)

3. Procedural vs. Substantive Unconscionability

a) Procedural: involved w/ K formation process, focusing on high pressures

asserted by the parties, fine print of K, misrepresentation, or unequal

bargaining power

(1) Refers to when one party was induced to enter the K w/out having a

meaningful choice

(2) Example – boiler plate clauses, high pressure salespeople, illiterate

consumers, person drugged and induced to sign K, etc.

b) Substantive: involved w/ content of K terms (e.g. inflated prices, unfair

disclaimers, termination clauses)

(1) Is a K term unduly fair or one-sided

(2) Example – excessive price, modification of either seller or buyer’s

remedies

(3) Last Penny Clauses

(a) Generally held to be unenforceable

(b) Clauses state that all products under installment plan will be

forfeited if at any point consumer defaults on payment – even if

only one penny left

c) *When both procedural and substantive unconscionability are present, the

case is strongest for finding unconscionability

4. UCC 2-302: Unconscionable Contract or Clause

11

(1) If the court as a matter of law finds the contract or any clause of the

contract to have been unconscionable at the time it was made, the

court may:

(a) Refuse to enforce the contract, or

(b) Enforce the remainder of the K w/o the unconscionable clause,

or

(c) So limit the application of any unconscionable clause as to

avoid any unconscionable result.

(2) When it is claimed or appears to the court that the contract or any

clause thereof may be unconscionable, the parties shall be afforded a

reasonable opportunity to present evidence as to its commercial

setting, purpose and effect to aid the court in making the

determination.

b) UCC § 2-302 comment: Basic test is, whether in light of the general

commercial background and the commercial needs of the particular trade or

case, the clauses involved are so one-sided as to be unconscionable under

the circumstances existing at the time of the making of the K (Ryan v. Weiner

(pg. 576)

(1) Factors:

(a) Inadequacy of bargaining power (age, experience, education of

parties)

(b) Unconscionable financial terms

(c) Innocent failure on π’s part to understand transaction

(d) Predatory practices on part of ∆

5. Cases:

a) Industralease Automated & Scientific Equipment Corp. v. R.M.E. Enterprises

(pg. 583): (Substantive – modifying remedy)

(1) ∆ purchases trash incinerators from π. K between parties include

disclaimer on warranties in bold. Incinerators don’t work but π is still

required to pay. π sues ∆ for unpaid balance but ∆ denies liability

claiming that disclaimer of warranties was unconscionable. Court finds

the warranty disclaimers were unconscionable since ∆ had no other

alternatives (duress: sign 2nd K or not delivery of incinerators) and he

depended on π’s expertise.

(2) Other Defenses

(a) Duress

(b) Misrepresentation

(c) See UCC 2-313, 2-314, 2-316 for warranty disclaimers

b) Dillman & Associates, Inc. v. Capitol Leasing Co. (pg. 589): (equal footing –

no unconscionability)

(1) Copy machine lease found to not be unconscionable b/c

(2) Distinguishable from Industralease b/c:

(a) Terms were understandable and lessee accepted “as is”

(b) Disclaimer was repetitive (occurred in 3 places); conspicuous

(c) Parties had equal bargaining power (both savvy businessmen)

(d) Lessee was under no compulsion to lease (no duress-like

circumstances).

(e) Lessee did not rely on lessor in choosing a product

(f) Machine was not worthless – was unable to handle lessee’s

volume

(g) Lessor was not mfg so lessee could still sue mfg

12

c) Jones v. Star Credit Corp (p. 591): (excessive price/remedy of reformed K)

(1) π’s are welfare recipients who seek to avoid K where ∆ is charging

them nearly $900 for a $300 freezer on which they have already paid

$600. Ct reforms K to set price at $600 by finding that ∆’s actions were

unconscionable

(2) Ct found that ∆ took advantage of π’s financial situation that was

known by him. While financing was necessary and ∆ can charge higher

price for increased risk, the terms were excessively high.

d) In Re Lisa Fay Allen (pg. 594):

(1) Lease for washer/dryer not unconscionable b/c there was no

oppressive bargaining practice (lessee sought lessor out), lease was

written in understandable terms, terms were not unreasonably

favorable to lessor, and the purchase price was not shocking

H. Standard Form/Adhesion Contracts

1. Contracts of Adhesion: unequal bargaining power where terms were forced upon

one party by the other; cts will look closely at such K’s for unconscionability

a) Fairfield Leasing Corporation v. Techni-Graphics, Inc. (pg. 599): (adhesion

clause – 7th amendment right)

(1) Jury trial may be waived if done knowingly and intentionally, but cts

will indulge every reasonable presumption against waiver. ∆ has heavy

burden of proving that π knowingly, voluntarily, and intentionally

agreed to the jury waiver provision. Such a waiver must be

conspicuous and stand out in the K. Ct finds here that it was not

conspicuous (noticeable) and holds the waiver invalid.

2. RST 234/208: Unconscionable Contract or Term

a) If a K or term is unconscionable at the time the K is made, a court may refuse

to enforce the K, or may enforce the remainder of the K w/o the

unconscionable term, or may limit the application of the unconscionable term

to avoid unconscionable result

(1) Comment Factors: gross inequality of bargaining power,

unreasonably favorable terms for the stronger party, lack of alternative

for weaker party, lack of assent by weaker party, unfair surprise,

notice, and substantive unfairness

b) Caspi v. The Microsoft Network (pg. 612): (forum selection clause)

(1) class action regarding B of K and consumer fraud; ∆ moves to dismiss

based on forum selection clause in their online user agreement; π

claims they weren’t given adequate notice of the clause; ct holds

clause enforceable since it was clear and unambiguous and was

presented in a fair and forthright fashion (relies heavily on Carnival

Cruise Line v. Shute (pg. 613))

(a) Notice is important

(b) items value matters

3. Doctrine of Reasonable Expectations:

a) RST 237 comment f: Although customers typically adhere to standardized

agreements and are bound by them w/out even appearing to know the

standard terms in detail, they are not bound to unknown terms which are

beyond the range of reasonable expectation.

(1) Factors:

(a) Term is bizarre or oppressive

(b) Term eviscerates the nonstandard terms explicitly agreed to

(c) Term eliminates the dominant purpose of the transaction

13

b) RST 211: Standardized Agreements:

(1) Where the other party has reason to believe that the party manifesting

such assent would not do so if he knew that the writing contained a

particular term, the term is not part of the agreement.

c) C&J Fertilizer, Inc. v. Allied Mutual Insurance Co. (pg. 603): (reasonable

expectations doctrine)

(1) π buys burglary insurance from ∆. K required visible marks on entry of

building exterior in order to collect $. π never reads this. π sues. Ct

holds the clause is unconscionable and protected by doctrine of

reasonable expectations.

(2) Corbin Rule: MAJORITY RULE is that insured’s are not bound to know

the contents of the insurance K.

(3) Argument that ct got it wrong: president of C&J was aware of policies

like this

(4) Reasonable Expectations – both parties reasonable expected to insure

and pay for a theft accomplished by a non-employee w/ reasonable

proof of such theft

(5) Substantive Unconscionability – definition of burglary given by ∆ is not

in line w. common knowledge and not negotiated

(6) Procedural Unconscionability – clause was in small print and buried;

nor was it explained to π w/ not much education and no expertise in

such legal matters

d) Markline Co., Inc. v. Travelers Insurance Co. (pg. 608): (RE doctrine not

recognized)

(1) Similar theft case where the ∆ refuses to pay unless π shows visible

marks of burglary according to K.

(2) same facts as C&J (burglary) but court does not recognize doctrine of

reasonable expectations and even if it did, it would not apply since π

didn’t reasonable except coverage to include anything else.

(3) Argument that court gets it wrong: president testified that he thought

the coverage was complete; insurer was aware that π expected full

coverage; parties discussed requiring a burglar alarm be installed and

to notify insurer if it went off

4. Problem 5-5 (pg. 611): Representing Ms. Williams (all of her furniture is threatened

by repo)

a) Arguments that she should not be bound by agreement:

(1) K language does not actually permit repossession (note: always

examine clause to be sure they can do what they’re claiming they can

do – interpret narrowly so as to prevent them from doing it)

(2) Linguistic maze (Gladden pg. 611): language makes it unconscionable

(3) Unconscionability: Ryan v. Weider: w/ her education level, there is

likely unconscionability since they can come in and take all her stuff

even though she’s paid for all but one

(4) Article 9 of the UCC: Secured Transactions

(5) Consumer protection laws (jdx specific)

(6) Non-disclosure (Weaver case)

(7) Doctrine of Reasonable Expectation (RST 211)

I. Modification of Contracts and Pre-Existing Duty Rule

1. Note: Look to facts to determine whether there was a modification, recession and/or

new contract, or waiver

2. Traditional Rules:

14

a) Common Law: in order for a K to be enforceable if modified, new

consideration was necessary

b) Pre-existing Duty Rule: a party who refuses to perform and coerces a promise

from the other party to the K to pay an increased compensation for doing

what he is already legally bound to do takes unjustifiable advantage of the

other party

(1) Alaska Packers’ Assoc. v. Domenico (pg. 627): (pre-existing duty)

(a) Ship workers agree to do work for a set price but then while at

sea, they stop work and demand more $. Supervisor agrees to

extra $. Ct finds that the K modification was not enforceable b/c

the workers had a pre-existing duty

(b) Also agent who modified K lacked power to do so

3. Modern Rules: (ways to get around Pre-exiting Duty Rule)

a) RST 89D(a): A promise modifying a duty under a K not fully performed on

either side is binding if the modification is fair and equitable in view of

circumstances not anticipated by the parties when the K was made

(1) 3 Requirements under 89D(a): modification is enforced only if

(a) The parties voluntarily agree

(b) The promise modifying the original K was made before the K

was fully performed on either side

(c) The underlying circumstances which prompted modification

were unanticipated by the parties

(d) The modification was fair and equitable

(2) Angel v. Murray (pg. 636): (RST § 89)

(a) π (garbage man) is under K w/ city and requests more $ due to

increase in residences; Ct holds the modification is enforceable

b) UCC 2-209: Modification, Rescission, and Waiver

(1) An agreement modifying a contract w/in this Article DOES NOT NEED

CONSIDERATION to be binding

(2) A signed agreement which excludes oral modification or rescission

except by a signed writing cannot be otherwise modified or rescinded,

but except as b/w merchants such as a requirement on a form supplied

by the merchant must be separately signed by the other party

(3) The requirement of the statute of frauds section of this Article must be

satisfied if the K as modified is within its provisions

(4) Although an attempt at modification or rescission does not satisfy the

requirements of subsection (2) or (3) it can operate as a waiver

(5) A party who has made a waiver affecting an executory portion of the K

may retract the waiver by reasonable notification received by the other

party that strict performance will be required of any term waived,

unless the retraction would be unjust in view of a material change of

position in reliance on the waiver

(6) Official comment: modifications must meet test of good faith

imposed by Act; effective use of bad faith to escape performance on

the original K terms is barred and the extortion of a modification w/o

legitimate commercial reason is ineffective as a violation of good faith

duty. (See 2-103 for good faith standard for merchants)

c) Schwartzreich v. Bauman-Basch (pg. 630) Rule: (mutual rescission)

(1) Provided there is mutual expressed intention, parties may formally

rescind K and enter into a new one regardless of how much time (if

any) exists between rescission and the new K (Note: this rule can be

15

used to get around CL rule that there must be new consideration for a

K modification – if there is not a modification but a rescission and a

new K formed, the CL rule wont apply)

(2) π words for ∆ and disagreement arose when π was to leave to work for

another, but ∆ kept him on for higher ay, only to fire him later before K

expired. Both parties have different account of facts, but ∆ asserts lack

of consideration disallowing modification of K. ct looks at evidence of

tearing up old K and finds for π

(3) 2 Step Process:

(a) Rescission of K based on some consideration

(b) New K is written on a clean slate

d) United States v. Stump Home Specialties MFG, Inc. (pg. 635) Rule: slight

consideration will suffice to make a K or a K modification enforceable (but

then look to see if there is duress)

J. Accord & Satisfaction

1. RST 281: an executory accord is an agreement by the parties by which one

promises to render a substitute performance in the future, and the other promises to

accept that substitute performance in discharge of the existing duty.

a) Creditor is held to its standard once time for performance ripens

b) If debtor breaches before t ripens, creditor can claim original amount

c) Creditor cannot unilaterally change terms before performance ripens or

debtors breaches

2. Checks – generally when there is a bona fide dispute, and the debtor sends a check

w/ works “payment in full”, cashing the check is deemed as accepting an offer of

accord and satisfaction.

3. Substitute Agreement

a) RST 279 – parties may make a substituted agreement by which the pervious

K is immediately discharged and replaced with a new agreement.

(1) Creditor can only sue for breach of new K, not any older obligation

(2) The more informal the substituted agreement, the more likely its an

accord

4. Rules

a) Common Law Rule: Where an amount due is in dispute, and the debtor

sends a check for less than the amount claimed and clearly expresses his

intention that the check has been sent as payment in full and not on account

or in part payment, the cashing or retention of the check by the creditor is

deemed an acceptance by the creditor of the conditions stated, and operates

as an accord and satisfaction of the claim.

(1) Con Ed. v. Arroll (pg. 644): (accord and satisfaction – check)

(a) ∆ believes that he is being charged too much for his power bill

and sends payments to ConEd for a lesser amount (which

reflected an average of past bills) that clearly stated that the

payments operated as an accord and satisfaction of the amount

owed. All 5 checks were retained and deposited by ConEd.

Since ∆ honestly believed that he owed less, clearly stated

intention that payments operate as accord and satisfaction, and

since the checks were retained and cashed by ConEd, ∆’s

payments were effective as accord and satisfaction.

b) UCC 1-207: Performance or Acceptance Under Reservation of Rights

(1) A party who with explicit reservation of rights performs or promises

performance or assents to performance in a manner demanded or

16

offered by the other party does not thereby prejudice the rights

reserved. Such words as “without prejudice,” “under protest” or the like

are sufficient.

(2) Subsection (1) DOES NOT APPLY TO AN ACCORD AND

SATISFACTION.

c) UCC 3-311: Accord and Satisfaction by Use of Instrument (see pg. 111 of

supp)

17

III. Parol Evidence Rule (Oral declarations)

A. Background

1. Parol Evidence Rule: When 2 parties have made a K and have expressed it in a

writing to which they have both assented as to the complete and accurate integration

of that K, evidence (whether parol or otherwise) of antecedent (previous)

understandings and negotiations will NOT be admitted for the purpose of varying or

contradicting the writing (Corbin).

a) Parol – generally oral, but can be other extrinsic evidence that could/could not

be allowed to explain the purpose and meaning of the K

b) Parol evidence rule bars admission of evidence regarding prior (antecedent)

or contemporaneous agreements but NOT agreements made after the writing

c) Parol evidence CANNOT be used to contradict an unambiguous writing (ct

makes this determination)

(1) Anti-contradiction Rule: applies whether the integration is complete or

partial; you cannot intro parol evidence that would contradict terms in

the written instrument

(a) Baker v. Bailey (p. 665): (total integration, anti-contradiction)

(i) In absence of fraud, duress, mutual mistake, all extrinsic

evidence must be excluded if the parties have reduced

their agreement to an integrated writing that is clear and

unambiguous. All prior and contemporaneous

negotiations or understandings of the K are merged once

that K is reduced to writing.

(ii) Π had a water use agreement w/ ∆ and later sued when

∆ refused to provide water to 3rd party to whom π was

going to sell land. Ct reversed and disallowed parol

evidence showing general understanding was to allow all

subsequent purchasers to use water. Ct held that writing

was explicitly in only limiting water use to π and not

assignees.

(2) Anti-supplementing/varying/altering Rule: UCC 2-202(b) – if total

integration, parol evidence of additional terms not allowed

(a) Masterson v. Sine (pg. 658): (anti-supplementation rule)

(i) π conveyed land to ∆, but reserved option t buy back. π

goes bankrupt and trustee attempts to exercise the buy

back clause, but ∆ refuses saying it was a right personal

to π only – not his assigns. Ct must determine if the ct

was correct in not allowing ∆ to present parol evidence

showing π intended grant to be personal. Ct allows

evidence based on anti-supplementary rule and finds for

∆ as:

(a) Deed does not says it’s a complete integration

(b) Deed is silent on assignability

(c) Deed too formal to include additions to it

(ii) Dissent argues

(a) Basic property law indicates all property

conveyances are normally assignable

(b) It would be easy to change deed to say if nonassignable

(b) Parol evidence can only be used for elements of the agreement

NOT reduced to writing

18

(c) Collateral agreements must be analyzed to determine whether

the parties intended the subjects of negotiation it deals with to

be included in, excluded from, or otherwise affected by the

writing. Circumstances at the time of the writing may also aid in

the determination of such integration.

(d) RST 240(1)(b) permits proof of collateral agreement if it is such

an agreement as might naturally be made as a separate

agreement by parties situated as were the parties to the written

K

(e) UCC 2-202, comment 3: if additional terms are such that if

agreed upon would certainly have been included in the K in the

view of the court, then evidence of their alleged making must be

kept from the trier of fact (strict test)

2. Complete vs. Partial Integration

a) Complete integration: a writing is complete if it integrates all prior or

contemporaneous terms (RST 228)

(1) A finding of a complete integration will preclude use of parol

evidence

(a) Approaches to determine whether there is a complete

integration:

(i) Williston: look ONLY to the writing itself (4 corners of the

agreement)

(ii) Corbin: Must look at BOTH the writing and everything

else (contextual), including the alleged parol agreement,

to determine if there is a complete integration

(b) Generally, cts will find a complete integration if there is a

MERGER CLAUSE (clause saying that written instrument

embodies all past negotiations and agreement)

b) Partial integration: if the written instrument is silent on whether it is a total

integration, it may be considered a partial integration of K terms.

(1) Parol evidence rule DOES NOT apply to part that is not integrated

(only the part that is)

3. Policy Rationales Behind Parol Evidence Rule

a) Avoiding fraud in K’s

b) Implementing the intentions of the parties

c) Guarding against unintentional deception

d) *REMEMBER: if these policies are not being effectuated, Llewellyn would say

that where the reason stops, there stops the rule (thus, the exceptions, see

below)

B. UCC 2-202: Final Written Expression: Parol or Extrinsic Evidence

1. Terms, w/ respect to which the confirmatory memoranda of the parties agree or

which are otherwise set forth in a writing intended by the parties as a final

expression of their agreement w/ respect to such terms as are included therein, may

NOT be contradicted by evidence of any prior agreement or of a contemporaneous

oral agreement BUT may be explained or supplemented by:

a) Course of dealing or usage of trade or by course of performance; and

b) Evidence of consistent additional terms, unless the court finds the writing to

have been intended also as a complete and exclusive statement of the terms

of the agreement

C. Exceptions to the Parol Evidence Rule

19

1. Collateral Contract Exception: if agreement is collateral to the written K, it is not

barred by rule.

a) Mitchell v. Lath (pg. 654): (general parol evidence case)

(1) Icehouse case; Parol evidence rule covers situations where there is an

attempt to modify a K by parol, but does not apply when there is a

parol collateral K distinct and independent of the written agreement.

(2) Π sues ∆ who conveyed land to her, but failed to remove icehouse.

Deed did not contain this oral agreement. Ct has 3 part test to

determine is parol evidence of this agreement is allowed

(a) Agreement must be collateral to written one; cant have separate

basis of consideration

(b) Cannot contradict express or implied provisions of written

agreement

(c) Must be one not ordinarily put in writing (π loose here and ∆

wins)

(3) Dissent

(a) Written agreement alone cannot show full and complete

agreement w/out referring to oral agreements and negotiations

(b) Agreement to remove icehouse and to convey land were

mutually dependent

2. Ambiguity Exception: oral agreement is not contradictory but merely clarifies an

ambiguous K; UCC 2-202(a) allows introducing evidence of course of performance,

course of dealing and trade usage.

a) Pacific Gas and Electric Co. v. G.W. Thomas Drayage & Rigging Co. (pg.

678): (ambiguity rule)

(1) π argues that the indemnity clause makes the ∆ liable for damage to

π’s property but ∆ argues that the clause only indemnifies them from

damages to third parties; Court reasons that the word “indemnity” is

ambiguous and therefore parol evidence should be admitted

(2) TEST: if the court decides, after considering all the evidence, that the

language of the K, in the light of all the circumstances, is fairly

susceptible of either one of the two interpretations, extrinsic evidence

relevant to prove either of such meanings is admissible

b) Trident Center v. Conn. Gen. Life Ins Co. (pg. 681): (ambiguity rule)

(1) Criticizes the Pacific Gas opinion saying that parties can be extremely

clear and yet risk that at point of dispute the ct will negate writing and

say it could mean different things. This could lead to costly and

protracted litigation, frustration and delay.

3. Condition Precedent Exception: if there is a condition precedent to the legal

enforceability of a written K, cts sometimes hold parol evidence admissible to prove

the condition

a) Harrison v. Fred S. James, P.A., Inc. (pg. 688): (merger clause)

(1) employee alleging the employer breached a term of an oral K that he’d

been employed for 2 years but there is a later written K that includes

both a merger clause and says the writing supersedes all prior

agreements and allows for a 15 day notice period before termination

ends; employee is terminated and sues; Ct says the K is unambiguous,

so then ct looks to see if the K is ineffectual in and of itself; employee

argues 5 theories: fraud, duress, mistake, lack of meeting of minds,

and no consideration ct doesn’t really buy any of them

(2) Arguments that the parol evidence should have been admitted:

20

(a) Argument that this was a new K, not a modification

(Schwartzreich)

(b) Even if it was a modification, modifications don’t necessarily

need separate consideration (think 2-209 assuming it applied)

(c) Assuming the first K was made, it might not be enforceable

since it was not performed w/in one year and thus would be

unenforceable under SOF

4. Fraud, Duress, & Mistake Exception: evidence attacking validity of the K itself can be

admitted.

5. Promissory Estoppel Exception: most jdx are not comfortable w/ this one, especially

if there is no separate consideration.

21

IV. Contract Interpretation

A. Common Law Rules of Interpretation:

1. Language in a K is interpreted according to its ordinary meaning

2. K shall be construed as a whole so that all its parts are harmonized as much as

reasonably possible

3. K is interpreted in light of its underlying purpose/intention of the parties

4. If K is susceptible to more than one interpretation, pick the one that is most fair

and customary such as prudent men would naturally execute it and reject the

interpretation that is inequitable, unjust, or unusual (p. 707 Sutter Insurance)

a) Turner Holdings v. Howard Miller Clock Co. (pg. 702): HMCC was to be

obligated to THI for success fees after termination of K for any company

which as been under consideration; dispute was over the meaning of “under

consideration”; Ct uses the above rules of interpretation to determine that the

∆’s interpretation of “under consideration” was too narrow and goes with the

commonly understood meaning thus holding that the language was not

ambiguous.

(1) Rule: one party’s un-communicated understanding concerning the

specialized meaning of K language is not binding on the other party.

5. Expression of certain things excludes other things (see Haines v. City of New York,

below)

B. Statutory Rules of Interpretation:

1. RST 201: Whose Meaning Prevails

(1) Where the parties have attached the same meaning to a promise or

agreement or a term thereof, it is interpreted in accordance w/ that

meaning.

(a) If parties attach same meaning to K – use that meaning

(2) Where the parties have attached different meanings to a promise or

agreement or a term thereof, it is interpreted in accordance with the

meaning attached by one of them if at the time the agreement was

made

(a) That party did not know of any different meaning attached by

the other, and the other knew of the meaning attached by the

first party; or

(b) That party had no reason to know of any different meaning

attached by the other, and the other had reason to know the

meaning attached by the first party

(3) Except as stated in this Section, neither party is bound by the meaning

attached by the other, even though the result may be a failure of

mutual assent.

b) Berke Moore Co. v. Phoenix Bridge Co. (pg. 699): (trade usage is meaning)

(1) π attached meaning to construction K to include construction of all

sides of bridge, but ∆ maintained it only applies to top of bridge. Ct

decided that ∆’s meaning is correct as payment was in square yards,

customarily applies just to top surface measurements.

(2) This is odd as ct is giving deference to subjective meanings rather than

objective manifestations. Still appears to be correct outcome.

1. UCC 1-203: “Agreement” means the bargain of the parties in fact as found in their

language or by implication from other circumstances including course of dealing or

usage of trade or course of performance

2. UCC 2-208: Course of Performance or Practical Construction

22

(1) Where the contract for sale involves repeated occasions for

performance by either party with knowledge of the nature of the

performance and opportunity for objection to it by the other, any course

of performance accepted or acquiesced in without objection shall be

relevant to determine the meaning of the agreement

(2) The express terms of the agreement and any such course of

performance, as well as any course of death and usage of trade, shall

be construed whenever reasonable as consistent w/ each other; but

when such construction is unreasonable, express terms shall control

course of performance and course of performance shall control both

course of dealing and usage of trade

(3) Subject to the provisions of the next section on modification and

waiver, such course of performance shall be relevant to show a waiver

or modification of any term inconsistent w/ such course of performance

(a) NOTE: difference b/w course of performance and waiver is very

important!! It makes a difference as to what interpretation is

adopted

(b) If there is only one occurrence, then it is treated as a waiver

(see waiver prov)

3. UCC 1-205: Course of Dealing and Usage of Trade

(1) A course of dealing is a sequence of previous conduct b/w the parties

to a particular transaction which is fairly to be regarded as establishing

a common basis of understanding for interpreting their expressions

and other conduct.

(2) A usage of trade is any practice or method of dealing having such

regularity of observance in a place, vocation or trade as to justify an

expectation that it will be observed w/ respect to the transaction in

question. The existence and scope of such a usage are to be proved

as facts. If it is established that such a usage is embodied in a written

trade code or similar writing, the interpretation of the writing is for the

court.

(3) A course of dealing b/w parties and any usage of trade in the vocation

or trade in which they are engaged or of which the are or should be

aware give particular meaning to and supplement or qualify terms of an

agreement

(4) The express terms of an agreement and an applicable course of

dealing or usage of trade shall be construed wherever reasonable as

consistent w/ each other; but when such construction is unreasonable

express terms control both course of dealing and usage of trade and

course of dealing controls usage of trade.

(5) An applicable usage of trade in the place where any part of

performance is to occur shall be used in interpreting the agreement as

to that part of the performance

B. Hierarchy of Interpretive Tools Under the UCC

Express Terms of K

I

Course of Performance

I

Course of Dealing

I

Usage of Trade

23

Cases:

1. Nanakuli Paving & Rock Co. v. Shell Oil Co., Inc. (pg. 709): (trade usage, course of

performance)

a) Π sues for breach of K when ∆ asphalt supplier does not honor price

protection when it has done so in past. ∆ has in K that posted price controls.

Cts finds for π based on trade usage and course of performance.

b) Trade Usage

(1) All other paving material supplies in area offer price protections, so

evidence that ∆ should have as well

(2) Ct says trade usage may apply to place or trade

(a) Place factor applies as ∆ was in the same mkt as everyone else

(b) ∆ also part of general trade, not requiring specific knowledge on

his part or extra burden

(c) Paving mkt is small, so ∆ is likely to know of such usage

(i) agent knew

c) Course of Performance

(1) ∆ offered protection before – should do it again

(2) ct applies complete negation test –so long as the term is not

negated, then it is ok to incorporate trade usage/course of performance

evidence.

D. K Interpretation and Gap Filling w/ a little Parol for fun...

1. Greenfield v. Philles Records, Inc. (pg. 674): record K was silent as to whether co.

could issue licenses to 3rd parties to use π’s recordings. Ct held the agreement

should be construed in accord w/ parties’ intent and the K is the best evidence of

such intent; if a K is unambiguous, the Ct is not free to alter it; since the recordings

became property of ∆, ∆ could reproduce them in any form and when read as a

whole, seemed that ∆’s were allowed to license to 3rd parties

C.

24

V.

Gap Filling

A. Gap Filler per se – K is truly silent on a term and ct fills it in based on law (UCC)

B. Two methods:

1. Court may fill gap by interpreting written K language in light of extrinsic evidence and

the circumstances

2. Court may purport to ascertain intentions even though the parties clearly had no

intentions

C. RST 204: an essential term necessary to determine rights/duties may be supplied by the ct.

D. UCC 2-204(3): Even though one or more terms are left open, a K for sale of goods does

not fail for indefiniteness if the parties have intended to make a K and there is a

reasonably certain basis for giving an appropriate remedy (see 2-305 – 2-311); the more

terms the parties leave open, the less likely it is that they have intended to conclude a

binding agreement, but their actions may be frequently conclusive on the matter despite the

omissions.

E. “Reasonable Time” Rule: where parties have not clearly expressed the duration of a K, cts

will imply that they intended performance to continue for a reasonable time (if a duration

may be fairly and reasonably supplied by implication, a K is not terminable at will)

1. Exception: (p. 723) rule does not apply to K’s for employment or exclusive agency,

distributorship or requirement K’s. In these situations, K is terminable at will.

2. Haines v. City of NY (pg. 721): (omitted term replaced w/ reasonable term)

a) Π town sues ∆ city, which has promised to build, maintain, and extend sewer

facilities in return of promise to use town’s creek for water. ∆ refuses to

expand as plant is already operating at full capacity.

b) Issue – how long must ∆ maintain plant since K is silent on duration?

(1) Cts says for a reasonable time

c) Even though the city at one time extended the line, this is not course of

performance since it only happened once (thus was a waiver).

F. “Time of Delivery” Rule: where parties have reached an enforceable agreement for sale of

goods but omit terms of payment, the law will imply, as part of the agreement, that payment

is to be made at time of delivery.

1. Southwest Engineering Co. v. Martin Tractor Co. (pg. 729): (UCC 2-204(3))

a) Π sues ∆ when ∆ fails to deliver generator based on negotiations. Π has to

cover and sue for damages. ∆ points to fact that there was no written K and a

memo showing agreement on the 2 choices of generators was silent on

payment terms. Ct cites 2-204(3) and says that K still stands and that the

payment terms were incidental as parties did not show extrinsic evidence

showing price was a deal breaker.

G. Gap-Filler UCC Provisions (for when the fact-finder determines a K exists but certain

terms absent):

1. UCC 2-314 –implied warranty of merchantability – absent express terms, this fills

gap.

2. UCC 2-305 – open price term

3. UCC 2-306 – quantity

4. UCC 2-308 – place of delivery

5. UCC 2-309 – time of delivery

6. UCC 2-310 – terms of payment

25

VI.

Good Faith

A. Rules

1. UCC 1-203: Every K or duty w/in this Act imposes a duty of good faith in its

performance or enforcement

2. RST 205: Duty of Good Faith and Fair Dealing: Every K or duty within this Act

imposes a duty of good faith and fair dealing in its performance or enforcement

a) Meaning of Good Faith: varies somewhat w/ context; good faith

performance or enforcement of a K emphasizes faithfulness to an agreed

common purpose and consistency w/ the justified expectations of the other

party; excludes conduct characterized as involving “bad faith” b/c it violates

community standards of decency, fairness or reasonableness; remedy varies

w/ circumstances

b) Good Faith Performance: subterfuges and evasions violate the obligation of

good faith performance even though the actor believes his conduct to be

justified. Fair dealing MAY require more than just honesty

(1) Instances of bad faith recognized in judicial decisions

(a) Evasion of spirit of bargain

(b) Lack of diligence and slacking off

(c) Willful rendering of imperfect performance

(d) Abuse of power to specify terms

(e) Interference w/ or failure to cooperate in other party’s

performance

3. UCC 2-306: Output Requirements and Exclusive Dealings

(1) A term which measures the quantity by the output of the seller or the

requirements of the buyer means such actual output or requirements

as may occur in good faith, EXCEPT that no quantity unreasonably

disproportionate to any stated estimate, or in the absence of a stated

estimate, to any normal or otherwise comparable prior output or

requirements may be tendered or demanded

(a) Actual output should be in good faith

(b) Output should not be unreasonably disproportionate to prior

estimate or prior output

(2) A lawful agreement by either the seller or the buyer for exclusive

dealing in the kind of goods concerned imposes, unless otherwise

agreed, an obligation by the seller to use best efforts to supply the

goods and by the buyer to use best efforts to promote their sale

b) 2-306 Comment: Subsection (2) makes explicit that contracts are held to

have impliedly, even when not expressly, bound themselves to use

reasonable diligence as well as good faith in their performance of the K.

c) Feld v. Henry S. Levy & Sons (pg. 747): (output K)

(1) bread crumb maker agrees to sell all crumbs produced for a 1 yr

period; maker performs for most of the year and then stops b/c he says

making it is not economical; when buyer claims breach, maker’s

defense was that the K did not require that bread crumbs be produced

until end of the K but that whatever crumbs were produced were to be

sold to buyer;

(2) 2 forms of K’s: requirement K’s and output K’s

(a) We have an output K here, so UCC 2-306 applies

(3) Output Ks present 2 questions:

(a) Consideration: does such a K fail b/c of lack of mutuality of

obligation?

26

(b) Definiteness: since the quantity is so hard to predict, it is hard to

define

(4) Ct found that good faith required continued production of crumbs even

if no profit; maker would be justified in good faith in ceasing if losses

from continuance would be more than trivial (which is a question of

fact)

B. Common Law Rules

1. Good faith applies to “at will” K’s too; all K’s contain an implied covenant of good

faith and fair dealing and thus a bad faith termination is a BoK

a) Fortune v. National Cash Register Co. (pg. 734): (general good faith case)

(1) Employment K terminable at will; employee terminated w/o cause

(which was allowed by K) but on the brink of making a sale of which he

would have gotten large commission; jury found he was terminated in

bad faith. Ct finds for π employee.

2. Tymshare, Inc. v. Covell (pg. 740): K that ties commission to a quota but allows the

employer to retroactively raise quota and employer has sole discretion at any time

a) Court found that this did not mean that it could be done for any reason

whatsoever no matter how arbitrary, so no bad faith could reasonably be

found

27

VII.

Conditions

A. Terminology

1. Condition: an event, not certain to occur, which must occur, (unless its nonoccurrence is excused) before performance under a K becomes due (RST 224)

(1) A fact upon which the parties’ duties depend

(2) Operates as a condition only by agreement of both parties

(3) Made to postpone an instant duty and its occurrence/being satisfied

creates a duty

(4) Indicated by the word “shall” (usually)

(5) NOTE: failure of condition DOES NOT warrant a BoK – just means the

other party’s obligation to perform does not mature (unless of course

there is a specified promise to perform the condition)

(6) Reasons to impose a condition on duty to perform:

(a) Shift risk of nonoccurrence to obligee

(b) Induce the obligee to cause the event to occur

b) Express Condition Precedent: what is required to occur prior to a duty

maturing

(1) If an express condition is missing, Ct turns to parol evidence, course of

performance, etc

c) Implied-in-law Condition Precedent: absent K language, X must occur before

Y

(1) Also called a “dependent covenant” or “constructive condition

precedent” meaning that it is not to be performed unless and until the

other party performs (as opposed to an “independent covenant” which

refers to a duty to perform independent of the other party’s duty to

perform)

(2) Rule: When a duty to perform has not matured, a party’s duty is

discharged when it is “too late” for the condition to occur

d) Implied-in-fact Condition: gap filler used to ascertain the intent of the parties,

which is based on a course of dealing b/w the parties and indicates one which

party has the obligation to perform first

2. Promise: a manifestation of intention to act or refrain from acting in a specified way,

so made as to justify a promisee in understanding that a commitment has been

made (RST 2)

a) Made by act(s) of ONE party to express intention

b) Its making creates a duty or disability in the promisor

c) Its fulfillment discharges a duty; non-fulfillment = breach & creates a right to

damages

3. Promissory Condition: event that is both a promise and a condition

4. Note – Express conditions require strict compliance; implied require substantial

performance

B. Express Conditions

1. Uses of Express Conditions and their Operation and Effect

a) General Principle: While a contracting party’s failure to fulfill a condition

excuses performance by the other party whose performance is so

conditioned, it is not, w/o an independent promise to perform the condition, a

BoK subjecting the non-fulfilling party to liability for damages

(1) Merritt Hill Vineyards Inc. v. Windy Heights Vineyard, Inc. (pg. 761):

(express condition only)

(a) Parties K to sell vineyard w/ express condition that seller will

produce title of insurance at closing. At closing no title is

28

produced and buyer refuses to go through w/ deal. Buyer sues

for return of deposit. CT says Buyer’s duty to pay was expressly

conditional on seller’s duty to bring title – therefore buyer’s duty

did not mature. Buyer can only get back deposit.

2. Fulfillment of Conditions

a) General Rule: Conditions which are express or implied must be exactly

fulfilled or no liability can arise on the promise which such conditions qualify

(Williston) – reasons is if parties expressly state/write condition they must

have meant it.

(1) Brown-Marx Assoc., Ltd. v. ES Bank (p. 768): (express condition

only) BoK action for failure to give the ceiling loan; lender defends w/

“failure of condition” and was thus under no duty to give ceiling loan; π

argues judge should adopt substantial performance doctrine; ct finds

sub. pef. not enough since this involved non-occurrence of a condition,

not non-performance of a duty (like Jacob v. Young, see below)

(2) Exception: “Substantial Performance” Doctrine: if there is a gap w/

regard to quality of performance, a builder must substantially perform

in order to satisfy an implied-in-law condition precedent to the owner’s

duty to pay; if there is substantial performance w/ no material breach,

duty to pay whole amount is triggered, less a reduction for the

difference in value (if any); DOES NOT APPLY IN CASE OF A

CONDITION – ONLY IN CASE OF A DUTY!

(a) Jacob & Youngs, Inc. v. Kent (pg. 763): K explicitly stated

Reading pipe was supposed to be used in building of house;

builder did not use it in some places; big question was whether

the builder substantially performed; if substantially performed,

duty to pay by owner is triggered