LabMakingYogurt - 3CBiologyCourseWork

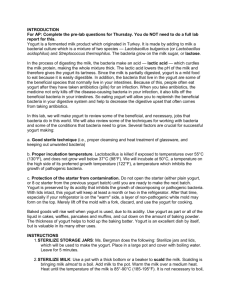

advertisement

Making Yogurt Lab SBI 4U Biotechnology Connections Labs All organisms need energy to live. Cellular respiration is the process they use to convert the energy stored in sugars into the quick energy of ATP. If oxygen is available, the mitochondria can perform their “energy generator” job and make a lot of ATP energy. This version of respiration is called aerobic respiration and it produces enough ATP energy to support large active, multicellular animals like you and me. If oxygen is not available, large organisms cannot produce enough energy to survive. That’s why we die if we cannot breathe. But even though there is no oxygen, some onecelled organisms can still digest sugars and make enough ATP energy to live and grow. This version of respiration is called anaerobic respiration. Anaerobic means “without oxygen”. Anaerobic respiration is used by bacteria and fungi and is also referred to as fermentation. There are two types of fermentation: Lactic acid fermentation which is used by bacteria (and how we make yogurt) and also occurs in muscle cells when they are oxygen-deprived like during a sprint race: Glucose --> ATP + lactic acid Alcoholic fermentation, which is used by yeast (a one-celled fungus) and how we make beer, wine, bread, and many other foods: Glucose → ATP + alcohol + CO2 Enzymes. The acceleration of a chemical reaction by some substance, which itself undergoes no permanent chemical change, is called catalyses. The catalysts of metabolic reactants are enzymes, which are involved in almost all chemical reactions in living organisms. Without enzymes, metabolic reactions would proceed much too slowly to maintain normal cellular functions. Some chemical reactions will occur with out enzyme action but they might take forever! Several factors are crucial for successful yogurt making: a. good sterile technique (i.e., proper cleansing and heat treatment of glassware, and keeping out unwanted bacteria) b. proper incubation temperature. The bacteria in yogurt are killed if exposed to temperatures over 55°C (130°F), and does not grow well below 37°C (98°F). We will incubate at 50°C, a temperature on the high side of its preferred growth temperature (122°F), a temperature which inhibits the growth of pathogenic bacteria. (Note that many recipes call for cooler temperatures than this. We find the results less dependable when incubation temperatures are lower.) c. protection of the starter from contamination. Do not open the starter (either plain yogurt, or 8 oz starter from the previous yogurt batch) until you are ready to make the next batch. Yogurt is preserved by its acidity which inhibits the growth of decomposing or pathogenic bacteria. With lids intact, this yogurt will keep at least a month or two in the refrigerator. INSTRUCTIONS 1. STERILIZE: Wash jars in warm soapy water. Fill kettle with water and bring it to a boil. Pour this boiling water over and into the jars and lids to sterilize them. 2. Measure out 4 cups of milk into the pan. Measure the pH of the milk. 3. STERILIZE: Use a pot with a thick bottom to scald the milk. Scalding is bringing milk almost to a boil. Warm the milk over a hot plate Heat until the temperature of the milk is 85°-90°C (185-195°F). It is not necessary to boil, and do not let boil over...what a mess! 4. Pour the milk into the four jars leaving some space to add the yoghurt culture. 5. COOL MILK: Let your jars of milk cool down. Keep the jar covered during this process. You may speed the cooling process by placing the jar in a pan of clean cold water to cool it down. Cool the milk to 50°C to 55°C (122°-130°F). Remove the jars of cooled milk from the cooling bath. 6. INOCULATE: We will use uncontaminated yogurt (it will say “live cultures” on the label) as a starter — our source of bacteria. Place two tablespoons full of yogurt into each jar and blend. Stir very well to thoroughly distribute the yogurt starter. Cover immediately with sterile tops. Tighten well. 7. INCUBATE: Place the jars into the cooler. Fill the bottom of the cooler with warm fresh clean water at a temperature of 55°C. The depth of the water should be as deep as it can be without the jars tipping over and below the lid lips. Place in a warm location. Check to see that the water in the cooler does not fall below 50°C (122°F). Close the cooler, place in warm place and let sit undisturbed for at least three hours. 8. After three hours the yogurt should look like yogurt and can be refrigerated until consumption. Stir in sugar, fruit or flavorings as desired. 9. Measure the pH of the completed yogurt. Activity is based on the making yogurt lab developed by Kim B. Foglia • www.ExploreBiology.com • ©2008 Name _____________________________ SUMMARY QUESTIONS 1. Why did we initially heat the milk to 90°C? 2. Why did we put the yogurt jars in boiling water? 3. Why did we cool the milk to 50°C before putting in the yogurt culture? 4. What is in the yogurt culture? What is the live culture in yogurt? Why are we adding it to the warm milk? 5. Why did we keep the milk at 50°C overnight? 6. What is biologically going on in the yogurt jars? What process? 7. What happened to the pH of the milk as it turned to yogurt? Why did this change occur? Why does this process of making yogurt preserve milk? 8. Why does the yogurt thicken? (hint! have you ever added vinegar to milk?) 9. Design an experiment to show that this process is due to live bacteria in the yogurt culture. History of yogurt 10. Where and when did the making of yogurt originate? 11. What was similar or different in how yogurt was produced compared to how we made it? 12. What is similar or different when yogurt is produced on a large scale today? (enzymes?) Supplementary work: 13. How many different spellings of yogurt are there?