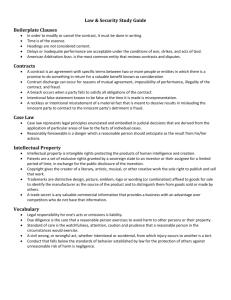

Vague Content in a Non-Vague World

advertisement