Greek Tragedy - eng2326

advertisement

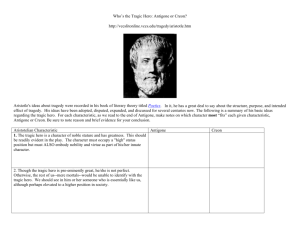

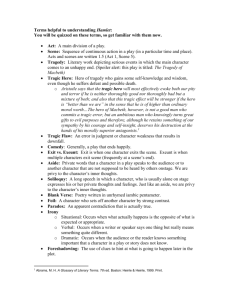

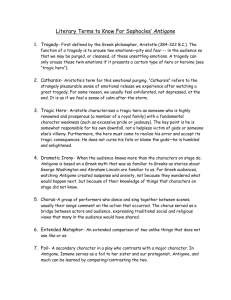

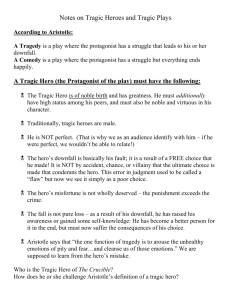

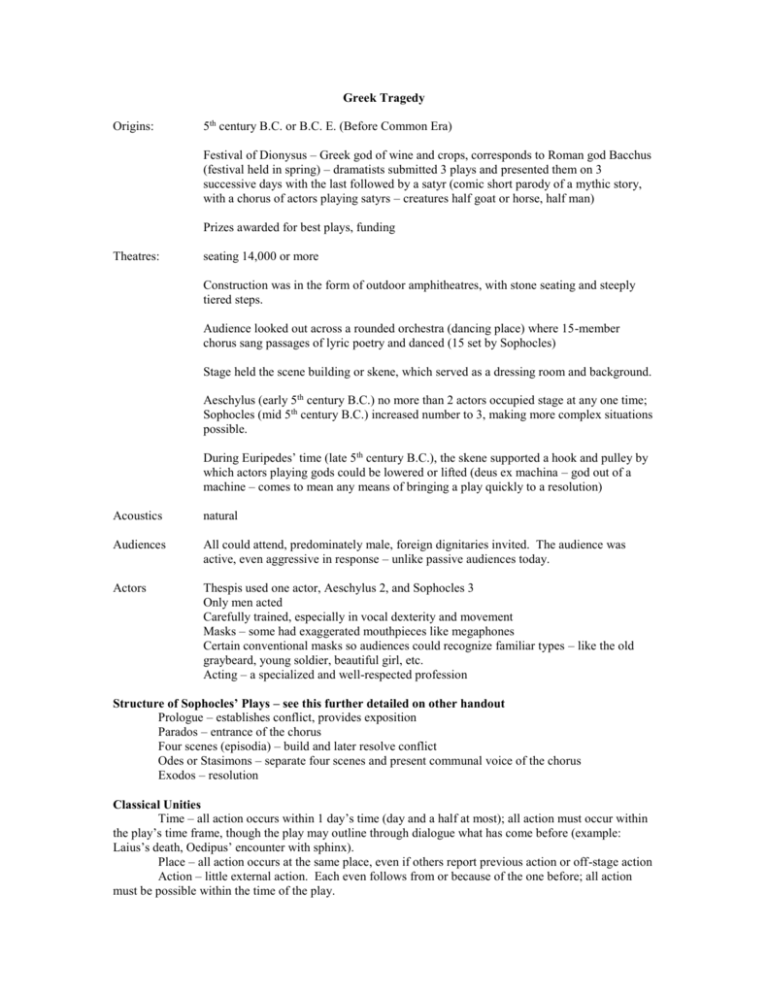

Greek Tragedy Origins: 5th century B.C. or B.C. E. (Before Common Era) Festival of Dionysus – Greek god of wine and crops, corresponds to Roman god Bacchus (festival held in spring) – dramatists submitted 3 plays and presented them on 3 successive days with the last followed by a satyr (comic short parody of a mythic story, with a chorus of actors playing satyrs – creatures half goat or horse, half man) Prizes awarded for best plays, funding Theatres: seating 14,000 or more Construction was in the form of outdoor amphitheatres, with stone seating and steeply tiered steps. Audience looked out across a rounded orchestra (dancing place) where 15-member chorus sang passages of lyric poetry and danced (15 set by Sophocles) Stage held the scene building or skene, which served as a dressing room and background. Aeschylus (early 5th century B.C.) no more than 2 actors occupied stage at any one time; Sophocles (mid 5th century B.C.) increased number to 3, making more complex situations possible. During Euripedes’ time (late 5th century B.C.), the skene supported a hook and pulley by which actors playing gods could be lowered or lifted (deus ex machina – god out of a machine – comes to mean any means of bringing a play quickly to a resolution) Acoustics natural Audiences All could attend, predominately male, foreign dignitaries invited. The audience was active, even aggressive in response – unlike passive audiences today. Actors Thespis used one actor, Aeschylus 2, and Sophocles 3 Only men acted Carefully trained, especially in vocal dexterity and movement Masks – some had exaggerated mouthpieces like megaphones Certain conventional masks so audiences could recognize familiar types – like the old graybeard, young soldier, beautiful girl, etc. Acting – a specialized and well-respected profession Structure of Sophocles’ Plays – see this further detailed on other handout Prologue – establishes conflict, provides exposition Parados – entrance of the chorus Four scenes (episodia) – build and later resolve conflict Odes or Stasimons – separate four scenes and present communal voice of the chorus Exodos – resolution Classical Unities Time – all action occurs within 1 day’s time (day and a half at most); all action must occur within the play’s time frame, though the play may outline through dialogue what has come before (example: Laius’s death, Oedipus’ encounter with sphinx). Place – all action occurs at the same place, even if others report previous action or off-stage action Action – little external action. Each even follows from or because of the one before; all action must be possible within the time of the play. Classic Tragic Hero as defined by Aristotle Taken from http://vccslitonline.cc.va.us/tragedy/aristotle.htm Aristotle's ideas about tragedy were recorded in his book of literary theory titled Poetics. In it, he has a great deal to say about the structure, purpose, and intended effect of tragedy. His ideas have been adopted, disputed, expanded, and discussed for several centuries now. The following is a summary of his basic ideas regarding the tragic hero: 1. The tragic hero is a character of noble stature and has greatness. This should be readily evident in the play. The character must occupy a "high" status position but must ALSO embody nobility and virtue as part of his/her innate character. 2. Though the tragic hero is pre-eminently great, he/she is not perfect. Otherwise, the rest of us--mere mortals--would be unable to identify with the tragic hero. We should see in him or her someone who is essentially like us, although perhaps elevated to a higher position in society. 3. The hero's downfall, therefore, is partially her/his own fault, the result of free choice, not of accident or villainy or some overriding, malignant fate. In fact, the tragedy is usually triggered by some error of judgment or some character flaw that contributes to the hero's lack of perfection noted above. This error of judgment or character flaw is known as hamartia and is usually translated as "tragic flaw" (although some scholars argue that this is a mistranslation). Often the character's hamartia involves hubris (which is defined as a sort of arrogant pride or over-confidence). 4. The hero's misfortunate is not wholly deserved. The punishment exceeds the crime. 5. The fall is not pure loss. There is some increase in awareness, some gain in self-knowledge, some discovery on the part of the tragic hero. 6. Though it arouses solemn emotion, tragedy does not leave its audience in a state of depression. Aristotle argues that one function of tragedy is to arouse the "unhealthy" emotions of pity and fear and through a catharsis (which comes from watching the tragic hero's terrible fate) cleanse us of those emotions. It might be worth noting here that Greek drama was not considered "entertainment," pure and simple; it had a communal function--to contribute to the good health of the community. This is why dramatic performances were a part of religious festivals and community celebrations. PAL: Perspectives in American Literature – A Research and Reference Guide – An Ongoing Project http://www.csustan.edu/english/reuben/pal/append/AXH.HTML I highly recommend this site. Read carefully this whole Appendix H. Be sure to scroll down to find Aristotle’s definition of tragedy. Then see beneath that what Dr. Reuben calls the central features of the Aristotelian archetype – what the previous expert called the summary of Aristotle’s basic ideas regarding the tragic hero – very similar, yet a little different.