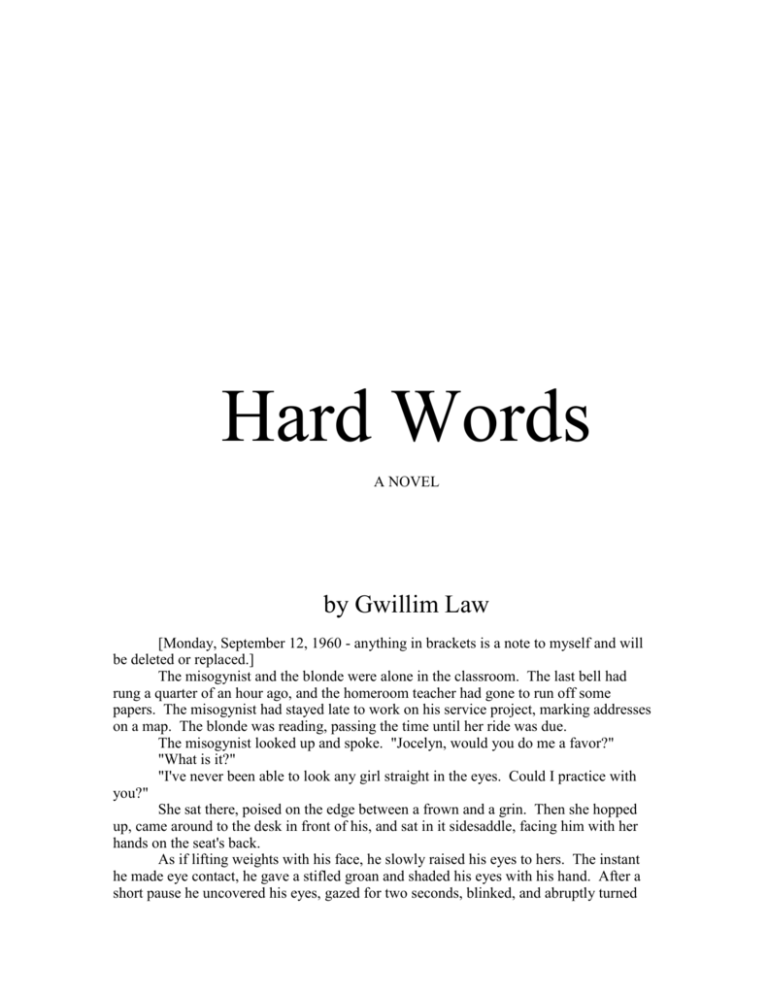

Hard Words

A NOVEL

by Gwillim Law

[Monday, September 12, 1960 - anything in brackets is a note to myself and will

be deleted or replaced.]

The misogynist and the blonde were alone in the classroom. The last bell had

rung a quarter of an hour ago, and the homeroom teacher had gone to run off some

papers. The misogynist had stayed late to work on his service project, marking addresses

on a map. The blonde was reading, passing the time until her ride was due.

The misogynist looked up and spoke. "Jocelyn, would you do me a favor?"

"What is it?"

"I've never been able to look any girl straight in the eyes. Could I practice with

you?"

She sat there, poised on the edge between a frown and a grin. Then she hopped

up, came around to the desk in front of his, and sat in it sidesaddle, facing him with her

hands on the seat's back.

As if lifting weights with his face, he slowly raised his eyes to hers. The instant

he made eye contact, he gave a stifled groan and shaded his eyes with his hand. After a

short pause he uncovered his eyes, gazed for two seconds, blinked, and abruptly turned

away. Setting his jaw in resolution, he focused once again on her eyes - eyes which any

but the most inveterate misogynist would have found it easy to look at. This time his

stare held firm for a full ten seconds.

She said, "You're doing great, Russ -" but the moment she spoke, he bent his eyes

back down to his desktop. "Aaah!" he cried. "Talking and looking! Too much at once!"

"All right, do you want to try again? I'll be quiet this time."

"All right," he replied, and raised his head once more.

She deliberately crossed her eyes.

His lips compressed with the effort, but he stared without wavering until she

laughed and got up. "I think you're getting the hang of it," she said. "My ride should be

here now." When she had left the room, he let a small, private chuckle escape and sat

with his eyes closed for a few minutes before he went back to his mapping.

She carried her books out to the curb, where an old brown Nash Rambler was

idling. The driver greeted her, "Hi, Lyn. What are you smiling about?"

"Hi, Dan. It was that Russ DeWitt. What an oddball."

"Oh. The nerd boy. Did he say it again?"

"Say what?" But she knew exactly what he meant. It was a running joke between

them.

"'Cigarettes are dettermental to saroobity.'"

"That's 'detrimental to salubrity'. No, he didn't say it this time. Something else

funny. I don't remember the exact words. Listen, Danny. I have to be home by five or

Mother says she'll ground me."

They spent about an hour at the YMCA, where Dan played pool with a couple of

his buddies, as Lyn looked on. Each of the three boys had his own gesture to herald a

successful shot. One of them pumped his arm; another gave a satisfied downward nod, as

if he were tracking the plunk of the ball with his nose. Dan's was a slight twist of his

hips, a sort of body English. Restrained gestures, but meant to be noticed. The game

concluded and the couple left with more than enough time to meet Lyn's deadline.

However, Dan stopped the car for a few minutes before they reached her street.

She actually walked in her front door at 5:01, but her mother was not one to fuss

over a minute's dereliction. "Is that you, Lyn?" Mrs. Marano asked brightly. "I'm glad

you're home, dear. Oops! Your hair needs a little fixing! I promised to pick up some

lawn posters. Could you watch dinner for me while I take a quick spin downtown?"

"Yes, Mother." She primped her hair in a hall mirror. "Do you think I have nice

eyes?"

Strafford High School was not large, and there were very few students or teachers

in it who didn't know that Russ DeWitt was a misogynist. He was more than willing to

let them know about it. In fact, it was thanks to him that many of them even knew what

the word meant. He was thus responsible for a small rise in Strafford's SAT average one

year when the word appeared on the test.

Not many of them knew or cared how he had come to be a misogynist. And yet,

it was a very simple recipe. He was sensitive and stubborn.

In second grade, he fell headlong in love with a cute little long-haired girl named

Patricia O'Finley. He had not learned the art of dissemblance, the wearing of the mask so

essential to civilized life. His passion declared itself not by words but by deeds. Having

read about Sir Walter Raleigh's gallantry, one day he spread his winter jacket over a mud

puddle in the playground for sweet Patty's accommodation. Sweet Patty wrinkled her

nose, walked in the opposite direction, and splashed through the next mud puddle in her

white lacy socks and Mary Janes.

I could list a number of similar episodes, but their cumulative effect was easy to

foresee. Russ became the target of ridicule, the object of obloquy, the butt of badinage.

Nothing subtle, nothing behind his back; Russ was easy pickings.

He reacted in a very normal way, one which has eased the growing pains of

countless other boys. He became, at least ostensibly, a girl-hater. Miss O'Finley

conveniently moved to another town, so he was granted a fresh start in third grade. He

was determined not to make the same mistake twice.

A couple of years later, his father unwittingly sealed Russ's fate. Russ was

grumbling at the dinner table over some foible of the female gender that had recently

come to his attention. His father said, "Just wait until you're sixteen and see how you feel

then." He answered not a word. He merely turned a key in his heart.

[Tuesday, September 20, 1960]

The Altrusa Club of Strafford met at The Spa every third Tuesday. As the

September meeting broke up into conversations, Mrs. Connie VanZandt leaned closer to

Miss Mildred Fahnestock. Mildred taught history at Strafford High School, and the

students liked to remark that she had read most of American history as it came out in the

daily papers.

"Mildred," Connie said, suppressing an impish grin, "my daughter Judy told me

the most wonderful story on you. I just had to find out if it was true."

"Oh, how sweet," the demure spinster simpered.

"She said you were teaching the class about Abelard and Heloise." Miss

Fahnestock's expression changed as if she had suddenly been illuminated from below.

"She said you told them how Heloise's father sent out some thugs to have Abelard

emasculated. Then you asked the class what 'emasculated' meant. That was injudicious,

Mildred."

"Well, my goodness," Mildred sputtered. "I was thinking of one meaning, and

one meaning alone. They gave him a sound thrashing."

"Judy says that no one answered, so you started going around the classroom,

asking each student in turn what they thought it meant. They were all stumped until you

got to Russ DeWitt. According to Judy, his exact words were, 'They cut off his ...

progeny.'"

"Pshaw. That impertinent boy. And I suppose you knew all about that other

meaning, Connie?"

"Well, after I looked it up in the dictionary, I did. Oh, come on, Mildred. Don't

look so glum. It was a harmless mistake. No one thinks you were trying to corrupt our

youth."

Mildred's expression finally softened. "I suppose I'd be a poor teacher if I

couldn't laugh at myself once in a while. Oh, dear. I don't know how I got through the

rest of the class period."

"While I'm talking with you, I wanted to ask something more serious. What do

you plan to do about the Great Debates? I mean, are you going to follow up on them in

Judy's class?"

"I most certainly am. This is history in the making. Never before has it been

possible for two presidential candidates to debate each other with the entire nation

watching. In American History, on Friday, I've assigned several students to take specific

issues and try to address them as they think the candidates would. Of course, it's not

quite as germane to World History, but in your Judy's class, we will spend the entire

period discussing our impressions on the Tuesday following the first debate."

"What do you think about the whole idea? Is this really a step forward for

democracy?"

"Unquestionably it is. How can it possibly hurt for millions of voters to hear both

sides of the questions of the day, presented in an absolutely fair arena?"

"'Absolutely fair'. Are you sure? Oh, the rules will be the same for both men.

But Senator Kennedy is so much more handsome than Mr. Nixon. I'm afraid that will

give him an unfair advantage with at least half of the electorate."

"Come now, Connie. Give our gender more credit than that. Many members of

this society," indicating the gathering with a gesture, "are professional women. Do you

suppose that they let themselves be swayed in their business dealings by the good looks

of salesmen or clients?"

"Mildred, I'm a businesswoman, and I have eyes. I just might be in a position to

answer that question better than you know."

[Saturday, September 24, 1960]

In Strafford, by September 24, blazes of fall color have usually popped out here

and there on the surrounding hillsides. The days, should they be blessed with sunshine,

are uniformly mild - exactly the temperature you would order, if the weather service

made deliveries.

Mr. Thurman, the advisor to the Honor Society, paused to admire a maple tree

and fill his lungs with fresh air before entering the school building. It was Saturday, the

day of the bottle drive. Students had previously passed around sign-up sheets to get the

name and address of anyone willing to contribute deposit bottles to the campaign. It was

those addresses that Russ had marked on a map of Strafford, now dissected into five

pieces. As he entered the auditorium, Mr. Thurman found ten students assembled. He

asked, "Who will be driving?" Lyn Marano and four boys raised their hands. He passed

out a piece of map to each of them.

"Now, who's riding shotgun? Russ, you go with Lyn."

Mr. Thurman had Russ in his English IV class, and had already had occasion to

reprimand him for starting out an oral report by addressing the class as "Friends, people,

and girls." Mr. Thurman took it as part of his mission to confound the plans of the

wicked. Compelling Russ to spend an entire afternoon with a girl would be a condign

punishment.

Russ took it with a face of stone. Nonetheless, once they were on the road, he

was not tongue-tied. On the way to their first stop, he mused, "Jocelyn, did you ever

consider that mankind might just be nature's way of releasing all the carbon that was

locked into the rocks during the Paleozoic Era?"

"Good heavens, what put that thought in your mind?"

"Looking at that thick exhaust from the dump truck in front of us. Well, think

about it. Carbon is a basic building block of life. Over the course of the eons, countless

living things have died, piled up in layers, and been covered by lava flows or by layers of

sediment. That leaves less and less carbon available for new life forms. Now has come

an era when humans are busy as beavers, digging up millions of tons of coal, pumping

millions of barrels of oil, bringing all that carbon back to the surface. We think it's all for

our convenience. But look at the long term. Once we've put enough carbon dioxide into

the air, the earth may no longer be habitable for us, but it will be a hospitable

environment for the lush tropical jungles that will grow to replace us."

"Don't forget diamonds."

"H'm?"

"Mining millions of carats of diamonds. Those are pure carbon."

"Good grief. Only a girl would think of that."

"'Only a girl'," she mimicked. "Well, I happen to think that human life is more

significant than just ... turning over the soil for the next crop."

"Wait ... here comes our first stop."

Lyn pulled over to the side and let Russ hop out, run up to the house, ring the

doorbell, collect the donated bottles, and stick them in the back seat. As they started off

again, she asked where the next stop would be.

"153 Cold Springs Road," he read. "Hm! 153 is an interesting number."

"How so?"

"Well, for one thing, it's the number of fish the disciples caught in the last chapter

of John."

"Really? What else?"

"It's also the total of the numbers from 1 to 17. But even better than that, it's

equal to the sum of the cubes of its digits."

"The sum of the cubes... Slow down, you're going too fast for me."

"Okay, the number 153 has three digits, one, five, and three. One cubed is one.

Five cubed is 125. Three cubed is 27. Add them up and you get 153 again."

"And there aren't any other numbers that do that?"

"Not that I know of."

"Well ... how about the number 1?"

"You know what, Jocelyn? You're right! And there's 0, too. Slow down: here

comes 153 Cold Springs Road right now!"

A few minutes later, they went by a house with a Brazilian flag flying just below

a U.S. one. Russ pointed it out, and added, "There are a Brazilian state capital and a U.S.

state capital that are named for the same person."

"Washington? Lincoln?"

"No, but I think you know both of the cities."

"Oh, I don't know. What are they?"

"Well, how many cities do you know in Brazil?"

"Rio de Janeiro ... Buenos Aires ... no, that's in Argentina, isn't it? São Paulo ...

that would be a saint's name, wouldn't it? Saint Paul? Ohhh! Saint Paul, Minnesota!"

"Very good, Jocelyn!"

As Russ continued to steer the conversation, Lyn began to find it a little uncanny.

It sounded as if he had written it all out in advance on three-by-five cards. No, that

couldn't be. So many of his remarks were related to unplanned sights along the route. He

hadn't even asked to partner with her. She felt a vague need to probe, to find out if he

was up to something. She got an opening when she saw a plumber's truck parked in the

neighborhood they were visiting.

"Oh, look! There's Dan's dad's truck! You know, my boyfriend Dan!"

"Sure. Everyone knows you're going with Daniel Travis. What's his middle

name?"

"Uh, Leroy."

"Okay, let me think for a minute. Daniel Leroy Travis. Varsity ... Ideal ...

Alienated ... Velleity, that's a good word ... Wait, I've got it. 'Ideally, isn't a rover'. That's

an anagram of 'Daniel Leroy Travis'."

She almost gasped. "How do you do that?"

"You ... rearrange the letters," he said matter-of-factly.

After a pause, she said, "So you've never smoked a cigarette in your life?"

"No, never."

"Why not?"

"Cigarettes would be detrimental to my salubrity."

She laughed delightedly. Russ didn't show any reaction. He only searched the

map for the next address.

Mr. Thurman's presence was only required twice for the bottle drive. His first

task, handing out the maps, was accomplished. Around three hours later, he was due to

collect the money from the returned bottles. It was certainly too beautiful a day to sit

indoors reading or grading papers. A perfect time to stroll around town.

Howard Thurman was a newcomer to Strafford, and still hadn't completely

oriented himself to the town. A new shopping center with a large parking lot was under

construction at a crossroads just outside of town, but for now downtown was still the

place to shop. Most of the stores were closed on Sunday, and quite a few were closed on

Saturday. Two blocks' walk took him to Main Street, past a soda parlor and a narrow

shoe-repair storefront. The first store he saw on Main was DeWitt's Books. This was the

only decent bookstore in town, and even so, it was struggling to stay in business. Mr.

Thurman enjoyed books. He stared at the window display, but then he turned aside, with

an unformulated aversion to having any further dealings with the DeWitt family today.

Making the unexpected movement brought him almost face to face with Connie

VanZandt.

She recovered first. "Well, Mr. Thurman. How have you been enjoying your

new house?"

"Oh, please, call me Howard. I'm not your customer any more. I'm very pleased

with the house, thank you."

"It isn't often that I find a fit so easily, Howard. Most of my clients have no idea

what they're looking for."

"If there's anything you can say about me, Connie, it's that I'm a man who knows

his own mind. Of course, it must be a lot easier to satisfy a single man than a whole

family. But you're headed away from your office. Closing up early?"

"No, I was going to the Uptown Tea Room for a late lunch."

"Ah! A cup of coffee would be just the thing right now! Would you mind if I

join you?"

There was just a flicker of a pause while Connie did some quick mental

calculations. She had an admirable flair for solving transcendental equations in terms

such as the younger-man factor, the gossip quotient, and the future-business function.

Apparently the result was positive, because a smile uncurled on her face and she said,

"Please do."

When they entered the Uptown, Howard headed for a booth at the back. Connie,

however, sat down, without comment, at a well-lit table in the center of the room. He

had to turn back when he realized she was no longer with him. Still, he smiled pleasantly

as he sat down. He dressed rather the English professor than the English teacher. He

wore horn-rimmed glasses with large rectangular lenses, a conservative tie that might

have been "old school" but wasn't, and a tweed sport jacket with, of course, elbow

patches. He had a squarish face with sharply defined features and appeared to be in his

early thirties.

For an opening conversational gambit, he began, "Rather amusing name for this

place. As if Strafford were big enough to have an uptown and a downtown! When I was

living in New York -"

"Oh, don't misunderstand. Around here, we say 'uptown' when we mean

'downtown'. No one talks about 'downtown Strafford'."

"Oh, I see." (Lost a pawn. Not important.) "Tell me about yourself, Connie."

"Not much to tell. Married Carl in 1942. One daughter, Judy, born in 1943.

She's in your English IV class. One son, Frank, born in 1948. Carl, having survived the

Battle of the Bulge and Remagen, was killed by a drunk driver in 1956."

"I'm very sorry to hear it. Was it very hard for you?"

"Well, you know, I have a hard time even answering that."

"That bad? Really?"

"No, that's not what I mean at all. Yes, it was terrible getting the news, and just as

bad telling the kids. But it's strange. When I look back, it just seems as if each day

presented its tale of challenges, I met them, and then I moved on to the next day. It

wasn't either hard or easy. I just never had to think about it."

"Was it your husband's death that made you go into real estate?"

"Actually, no. When Franky started first grade, I studied and got my license. I

was thinking more in terms of a career after the kids went off to college. Then when Carl

died, I only needed to take a couple of classes to reactivate my license."

"Do you think you'll ever marry again?"

"At this point in my life, I have no interest in marrying. The only thing is, I

wonder what Judy and Franky are missing out on, not having a father. Excuse me, Mr.

Thurman, but your foot seems to have wandered past the centerline of our table."

"Oops. My mistake," he said, uncrossing his legs. A waitress showed up at last,

and they gave their orders.

Howard continued, "You know, by far the grooviest feature of the house is the

built-in walnut bookcases. They give such warmth to the den. I've already filled many of

the shelves." He paused for questions, but not getting any, he went on, "One shelf for

first editions, another for autographed copies, another for old leatherbound books.... Who

is your favorite author, Connie?"

"I haven't had much time for reading since Carl died. I used to love Jane Austen."

"Ah! I have a wonderful old copy of Sense and Sensibility with Hugh Thomson

illustrations! You might like to see it sometime."

"I'm sure it's charming. Do you have any other hobbies besides book collecting?"

"Why, yes, I do. I'm a kind of amateur entomologist." As he said this, a new

light came into his eyes.

"You study insects?"

"Yes. But not just any insects. I've found it simply fascinating to delve into the

life cycle, and especially the feeding behavior, of the Blattidae."

"I'm not up on biology. That would be ...?"

"The cockroach family." Howard, it transpired, had read all the scientific

literature on these highly adaptable little creatures, as well as observing them closely in

their natural habitat. As he eagerly pointed out, "they're readily obtainable for study in

most American households." His sincere enthusiasm for the subject removed most of the

conversational burden from Connie's shoulders. There was some risk of it removing her

appetite as well, but years of motherhood had fostered her ability to turn her imagination

on and off as needed. She proceeded to enjoy her lunch, making only perfunctory

responses whenever Howard paused for a sip of coffee.

[Monday, September 26, 1960]

When Sputnik was launched in 1957, Russ DeWitt and Timmy Benk were already

entrants in the space race. That summer, they had built a homemade rocket using a

carbon dioxide capsule for an engine. Timmy lived on the same block as Russ, but he

also had access to his uncle's farm, fifteen minutes away by bicycle. They set up their

launchpad behind a silo and boosted their vehicle to an altitude of over ten meters, as

determined by triangulation.

This was the first of the team's many collaborations. They shared an interest in

Pogo, and between them they had a pretty complete collection of the works of Walt

Kelly. In Timmy's basement, they set up a model railroad layout combining both of their

individual sets. They operated a private bicycle repair shop in Russ's garage. For a

while, they organized some younger kids in the neighborhood and filmed silent

melodramas in eight-millimeter, complete with title cards. Currently, they were having a

contest, the object of which was to use a word in conversation that the other one didn't

know.

Timmy had reached the age when most Timmys prefer to be called Tim, but "Tim

Benk" sounded too harsh, too brusque. It reminded Timmy of the sound of a pinball

hitting the bumper. The issue was moot for Russ, who simply didn't use nicknames. He

always addressed his friend as Timothy.

On the evening of the first Kennedy-Nixon debate, Russ went to the Benk house

to watch. Russ and his father still didn't have a television set. When the debate ended,

Timmy and Russ retired to the front porch to escape the ruckus of Timmy's little brother

and two little sisters.

"Did the debate change your mind?" Timmy asked.

"No. I was for Nixon going into it, and I think Nixon presented his case better.

But Kennedy's going to win the election."

"How do you know?"

"I just know. Well, do you really want to hear it? This is why. The only way I

ever get what I want is by pretending not to want it. I forgot to pretend that I didn't want

Nixon to win."

"Man! Are you okay? I've never heard you talk like that."

"Yeah, it's fine."

"You aren't bothered that people call you a nerd, are you?" Timmy was thinking

of an instance he had heard earlier that day.

"Nerd? What's that?"

"You don't know what a nerd is?!"

"No, Timothy, I don't know what a nerd is. I guess that's one point for you."

"Well, one definition I've heard was, a nerd is a guy who goes around sniffing the

seats of girl's bicycles."

Russ was hardly any more enlightened than he had been. He pulled out a small

notebook from his pocket and made a mark on a score sheet under the name Timothy.

"Another definition of a nerd is someone who carries around five ballpoint pens in

a pocket protector," added Timmy.

Russ glanced at his breast pocket to count the pens. He said, "Anyway, I don't

care what people call me. Listen, Timothy, whom are your folks voting for?"

"They're going to cancel each other out. Dad's going for Kennedy, Mom's for

Nixon. Mrs. Marano came around with a lawn sign for Kennedy this afternoon. She said

Dad had asked for it. But Dad wasn't home, and Mom said no thanks."

The two boys contemplated the stars for a while, scanning the skies in a desultory

way for artificial satellites.

Timmy resumed, "You know, Mrs. Marano's daughter is a real dish."

Russ turned to look at him a moment. Then he drawled, "So why don't you ask

her for a date?"

"Aw, man! She's way out of my league."

"Huh. I guess every guy in Strafford High thinks she's way out of his league.

That must be why she's going out with Daniel Travis, who isn't bright enough to realize

it. It's a rebarbative bismer if you ask me."

"Wow! Great words, Russ! Explain?"

"Rebarbative means repellent. Visualize a woman flinching from a man with a

bushy beard. Bismer means a shame or abuse. Two points for me."

Russ somehow neglected to mention that he had spent three hours cruising around

town with Mrs. Marano's attractive daughter that weekend.

[Friday, September 30, 1960]

Dan Travis tightened the last lug nut and tapped the wheel cover on with a rubber

mallet. Then he lowered the jack and rolled it away to the side. Mikkelsen's Service

Station did have one bay with a hydraulic lift, but for changing only one tire, the s.o.p.

was to use a jack. Dan unrolled the sleeve of his t-shirt to extract a cigarette from the

pack he kept there. It was nearly 3:30, his quitting time, too late to begin another task.

Morgan "Red" Evans came back inside from filling a customer's tank with Cities

Service Hi-Test. "Hey, Danny boy! Through for the day already?"

"Yuh, I gotta go."

"Gonna pick up your girl Lyn? Don't be late, Danny. Girls don't like to be kept

waiting."

"That's a hot one! Nine times out of ten, I'm the one who's waiting for her!"

"Yeah, well, you got one who's worth waiting for. What does she see in a loser

like you, anyway?"

"Who's calling who a loser? I got my high school diploma, anyway. I haven't

seen yours anywhere."

"That's because I keep it in my sock drawer, underneath my Ph.D. from Harvard.

It's Friday night, lover boy. I hope you got something on the schedule for you and Lyn."

"You bet I do, wise guy. We're going to an early flick, a burger joint, and then the

football game."

"And then?"

"Whaddya mean, 'and then'? That's a big evening right there."

"I mean, does she put out?"

Dan gave the older man a shove. Red had crossed the line this time, and he knew

it. But Dan had actually been saving up a shove ever since the "loser" remark, which had

touched him in a tender spot. They squared off as if to begin a boxing match, but almost

immediately Dan turned away with a dismissive gesture.

"I'm going somewhere where the society is a little more refined," was his parting

salvo.

He was still smarting over the word "loser" as he drove to Strafford High. When

he picked Lyn up at the school, some of his thoughts came blurting out. "Lyn, you think

I have a future, don't you?"

"What's the matter, Danny? Has somebody been picking on you? Of course you

have a future. You're good with cars. People like you are needed. Cars are going to

need fixing for a long time."

"Yeah, that's what I think, too. I'm almost earning enough to make it on my own.

Not many guys my age can say that. I don't see why I couldn't have my own service

station some day. Mikkelsen makes real good money."

There was only one movie theater in Strafford, the Hobson. This week, "High

Time" with Bing Crosby was Hobson's choice. It was the story of a rich widower who, at

age 51, decides it's high time he got a college degree. [High Time premiered Friday,

September 16 in NYC.]

As they walked from the theater to the diner, Dan asked, "So... you're still

planning to go to college next year?"

"Yes, Dan, you know I am. But it's not going to be like in the movie. I mean, I

won't be taking classes with Fabian and Tuesday Weld."

"Lyn, with you in the classroom, the guys wouldn't even notice Tuesday Weld,"

he said earnestly, if a bit hyperbolically.

"Aw, you're sweet, Danny."

"Do you think you'd want to live in one of those fraternities?"

Lyn's laughter tinkled like a chandelier in a draught. Dan winced as if he had

been hit by a shard of cut glass.

"Fraternities are for guys, Dan. Girls live in sororities."

They had arrived at the Starline Diner. When they went in, Lyn immediately

spotted some of her friends together in a booth. Judy VanZandt was seated across from

the Chamberlain brothers, Mark and Clark. Clark, who was two years younger than the

others, was playing peg solitaire. Judy and Mark were playing table football by flicking a

folded matchbook cover back and forth. While they played, they were discussing which

of the latest hit songs were more likely to be guys' favorites versus girls'. When they

noticed the newcomers, Judy slid over to make room for Lyn to sit by her, and Dan drew

up a chair to the end of the table.

Judy said, "Speak up, Dan. You've been awfully quiet all evening."

"What do you mean? I just got here."

"That's more like it. Now you're the life of the party."

"So you think this party needs some life? Okay, here's one for you. What's round

and yellow and wears a ranger hat?"

After a few seconds, Mark said, "We give up. What?"

"Smokey the Pear!"

They laughed. The others were all reminded of jokes of the Moby Grape variety,

and started telling them. Clark probably knew more of these jokes than anyone else, but

was unable to make himself heard. He kept listening to Judy or Mark telling jokes that he

himself had been on the verge of reciting. Finally he raised his hand as if he were in

class.

"Why is a lion with a toothache like Morton Salt?" he asked.

"All right, why?" asked Judy.

"When it pains, it roars!"

Judy groaned and said, "Why is telling jokes like Superman's secret identity?

Clark can't!"

"Hey, hold on!" Mark said. "While I'm around, nobody picks on my kid brother

but me." He looked out at the street and saw some dead leaves blowing around. He said,

"It's really starting to look like fall out there."

Clark said, "Fallout? Quick! Head for the shelter!"

Everyone laughed, as the brothers exchanged grins. They had thought of that joke

a few days earlier, and were gratified at the success of its public debut.

"You know," Dan said, "we used to hear about fallout shelters all the time, but I

bet none of you has one, or even knows anyone who has one." None of them could

gainsay him. "My dad says there are no more than ten or twelve of them in the whole

town."

"Oh, I'm sure everyone comes to your dad to tell him before they put in their

shelter," Judy scoffed.

"The way he knows is, there's a special water filtration system that most of them

use. There's only one supplier of that system in this part of the state, and my dad found

out from him how many of them had been ordered. My dad actually installed one."

Clark and Lyn both asked "Who for?" at the same moment.

"He won't say. Most people who build one are worried that the neighbors will all

try to swarm in, if they ever need one."

Mark said, "That's sad. That's really sad. I mean, well, sure, there won't too many

people fit into one shelter, but to think of locking your friends and neighbors out and

leaving them to die...."

"That's a lot of hooey," Judy broke in. "If there's ever a full-scale nuclear war,

we're all going to die, and the ones who go soonest will be the luckiest."

"Cheery thought," said Mark. "I'd sooner go back to telling jokes." But the

joking mood had passed. They sat somberly for a while. Clark went back to his peg

solitaire. Then a waitress came to take their orders. Judy asked for a B.L.T. and a frappe.

Lyn ordered a hamburger, fries, and a Coke. Dan said, "Me, too." Mark said, "Me,

three." Clark said, "Me Tarzan. You, who?" No one even cracked a smile, so he weakly

amended, "I mean, same for me." The waitress nodded and departed.

Judy turned to Mark. "Mark, can you sit on your brother or something? I mean,

it's getting embarrassing."

This time Mark really took offense. "What the Sam Hill is the matter with you?

You've had a chip on your shoulder all evening. Cool it!"

Judy said, "Let me out, Lyn. I need to go powder my nose."

"Me, too," Lyn replied. They filed off to the ladies' room. Once inside, Lyn said,

"You're being awful, Judy. What's the matter?"

"Oh, can't a girl be herself once in a while?"

"Is it boy trouble?"

"You won't catch me having boy trouble. It's the boys who have Judy trouble."

"Well, is it that time of the month?"

"For Pete's sake. Do I have to spell it out for you? Do you remember what

happened four years ago tonight?"

"Ohhh! Judy! The night your father died."

"And the lady wins $64,000."

"Oh, Judy, I'm sorry." Lyn gave her a long hug. Then she looked at Judy's face

and saw glistening drops in the corners of her eyes. "Do you need a cry?"

"No. I'm all cried out."

"Judy, tell me about your dad."

Judy composed herself for a moment. "Carl Albert VanZandt. Born 1918, died

1956. Five foot ten, jet black wavy hair, deep dark brown eyes.... His eyelids were kind

of heavy. I remember the way he looked at me when I came in once, all covered with

mud. I can see his eyes now. I guess he was trying to be stern, but not doing a very good

job of it. It was more as if he was trying to ... memorize me.

"I'd like to say he was always there for me, but sometimes he wasn't. But when

he was there, he always made me feel I was important. I remember once or twice when

Mom gave him a shopping list and he took me along to the store. He talked to me, and

then he really listened. It made me feel grown up." She thought for a while.

"He must have been nice," Lyn said. "I saw him a few times, like Parent Night. I

thought he was very fond of you."

The restroom door rattled. Another patron wanted to get in. Lyn called, "Just a

minute." The two girls washed up and went back to their table.

"All right, I'll be a good girl now - for a while, anyway," Judy told the boys.

[Tuesday, October 4, 1960]

It was Russ's custom, after school, to bicycle to his father's bookstore. Some days

he had to restock the shelves. When that was done, he would select a book and retire to a

back corner of the store to read. From time to time, he would put on a new record: his

father liked to have classical music softly playing to set the mood in the store. At

dinnertime, he would bicycle home, fix a simple meal for himself and his father, and take

it back to the store for them to eat together. After that, his time was his own.

One brisk day in early October, while Russ was reading the loose cannon episode

in Victor Hugo's Ninety-three, he heard the tinkle of the chime on the shop door. Then he

heard a woman's voice say, "Good afternoon, Mr. DeWitt. My name is Emily Marano."

He inserted a bookmark in his book.

The voice went on, "I've been asking some of the merchants if they would be

willing to put a Kennedy poster in their display window."

"Oh, no, I'm sorry, Mrs. Marano. You know, some of my customers have strong

political convictions on both sides of the fence. I don't want to antagonize any of them.

I've always made it a policy to keep my store neutral ground."

"I understand, Mr. DeWitt. Do you mind if I ask if you personally are for

Kennedy?"

"Well, since you ask, no, I'm not. No, I expect I'll be voting for Nixon."

"And yet I see you have Senator Kennedy's book prominently on display." On the

counter next to the cash register there was a red, white, and blue rack with a dozen

paperback copies of Profiles in Courage.

"Of course. It's a good seller. But I believe you're misstating the case when you

call it Senator Kennedy's book."

"I beg your pardon?"

"Didn't you hear what Drew Pearson said about it? Something to the effect that

Jack Kennedy was the only man who won a Pulitzer prize for a book he didn't write?"

"Drew Pearson is nothing but a muckraking yellow journalist."

"Ah, ah, ah, Mrs. Marano. Ad hominem fallacy."

"You'll remember that the network retracted his insinuation."

By now, Russ had stood up to get a view of Mrs. Marano. She didn't appear to be

taking this personally; she still had a polite smile. But she in turn spotted him. "Oh," she

said, "you must be Russ DeWitt." He nodded mutely. "My daughter Lyn talks about

you. She said you -"

Russ desperately wanted to know what she said, but he even more desperately

wanted not to hear it in front of his father. He interrupted, "You mean that incident with

the slide rule?"

"What incident was that, Russ?" his father asked.

"Oh, it was nothing, Dad. In Chemistry class the other day, I set my slide rule

aside so I could write, and Benjamin Watson grabbed it. I reached for it, but he tossed it

across the room to Judith VanZandt. It was the middle of the class, so I couldn't do

anything right then. At lunch time, I asked Judith to give me the slide rule. She stuck it

into the waist of her skirt, right here," (he pointed to his hip) "and flaunted it at me. She

said, 'Go ahead, take it.' Well, you know I wasn't going to touch a girl's hip. I'd rather

buy a new slide rule. I just turned and walked away. Of course, Jocelyn, that's Mrs.

Marano's daughter, was enjoying the show. But it's okay. At the end of the day I found

my slide rule lying on my desk in homeroom.

"Guess I should go get dinner now."

He headed toward the door. Emily took that as her exit cue, and walked out as he

held the door for her. She continued along the main street, from one office or store to the

next, with mixed success. Presently she came to the real estate office where Connie

VanZandt was sorting through papers while waiting for a customer to show up.

Emily and Connie were acquainted mainly through their daughters. Emily was

the smaller of the two women. She wore owlish librarian glasses and a pleasant smile

which helped conceal the force of her personality. Connie was built like a statue on a

monument - perhaps Ceres, holding a scythe and a sheaf of wheat.

After they had greeted each other, Emily made her pitch for the poster. Connie

explained that only her boss could make the decision, but she accepted a poster to use in

case of an affirmative. Then she asked, "How have you been doing with the other

merchants?"

"About as well as expected. Many of them don't want to mix politics with

business." She suddenly thought of Russ's narrative, but, realizing that it reflected poorly

on Judy, decided to suppress it. Instead, she said, "For example, DeWitt's Books. That

man seems so sad. And his son behaves so strangely."

Connie suggested, "I suppose growing up without a mother can do that to a boy."

"Oh, I'd forgotten. How old was he when he lost his mother?"

"I think he was about six. It could explain his father being sad, too. Someone

should just give Vernon DeWitt a good shake and tell him to move on with his life."

"And who would do that, Connie? You?"

"Ah, there's the rub. He doesn't seem to let anyone get close to him. Me? No

thank you. I need a gloomy gentleman friend the way Kennedy needs a hearty

endorsement from Khrushchev."

[Saturday, October 8, 1960]

Saturday in the early afternoon, Howard Thurman sounded the door chime of

DeWitt's Books for the first time. He browsed for nearly an hour, lingering longest at

three bookcases full of used books in the back of the store. He uttered a low cry of

satisfaction, and went to the cash register with his purchases.

"I was simply thrilled to find this one," he told Vernon, handing him The Man

That Corrupted Hadleyburg in the Author's National Edition. "I have about six other

Mark Twain books in this same edition. Found four of them at the Strand Book Store in

New York when I was living there. I love to fill in the gaps in my sets."

"Glad I could help you," Vernon replied. "And Lolita, by Vladimir Nabokov. Do

you like Nabokov?"

"I hear he's terrific. My name is Howard Thurman, by the way. I teach English at

the high school. I have your son Russell in English IV."

"Vernon DeWitt." They shook hands. "You aren't going to be using the Nabokov

in your classes, are you? It's rather controversial, you know, at least for high school."

"Oh, no. It's only for my own literary enjoyment. No, I don't think you would

want your son reading Lolita."

"It's about the last thing he would want to read. It might as well be printed in

Russian, as far as he was concerned."

"Imagine. Suppressed in France, of all places, but freely available in the U.S.A.

And I used to think that all the Philistines lived here."

"All right. That will come to four dollars and thirty-nine cents."

"Mr. DeWitt - may I call you Vernon? Vernon, I expect that you must learn a

great deal about the people of Strafford as a book dealer. For example, you've just

learned that I collect old sets of books and used to live in the Big Apple."

"Oh, well, to tell the truth, I don't pay that much attention. I don't like to get

involved in other people's affairs."

"Really, now, Vernon. I'm not speaking of interference; it's only natural to take

an interest in what's going on in the world around you. Take me, for example. The

woman who found me the house I'm living in is a Mrs. VanZandt. She's a working

widow with two children. I have no personal stake in the matter, but I'm curious how she

manages the demands that must be placed on a woman in that situation. Who knows? I

might even be able to help her in some unexpected way."

"Hmmm. Mrs. VanZandt. I don't really recall her."

"Her office is only a few doors up the street from here."

"Oh, I think I know who you mean. Above average in height? Black hair? Lays

on her make-up a little too heavily?"

"You may have identified the right woman, but I'll have to enter a demurral on

your appraisal. I would say that she's right in touch with the latest cosmetic styles. In

New York, the women attending the opening of a new Broadway show look very much

like that. Have you by any chance noticed what kind of books she likes?"

"No... I don't know how long it's been since she came in here. I expect she gets

her books at the library."

"Oh, yes, the library. I have been rather disappointed with Strafford's excuse for a

public library. Not only is there a meager selection, it seems to consist mostly of cast-off

sentimental nineteenth-century novels. I suppose that's good for your business, though not much competition from the library?"

"That's one way to look at it. Although sometimes I think a better library might

get people more interested in books generally."

"That's the truth, I kid you not. Well, I suppose I must be going. I've really

enjoyed this little chat, Vernon. We must get together again."

[Thursday, October 13, 1960]

Miss Fahnestock spent the first ten minutes of each World History period going

over the news headlines. Each student was supposed to bring in one news item to

discuss. One Thursday, Sharon Arkwright reported, "Yesterday, Premier Khrushchev

interrupted a speech at the U.N. General Assembly. He called the speaker a jerk, and

then took off his shoe and pounded it on the table. Miss Fahnestock, I'm frightened. Just

think, a crazy man like that is able to send atom bombs to our country."

Russ raised his hand. "Miss Fahnestock, I don't think we can draw the conclusion

that Nikita Khrushchev is crazy. I read a book on game theory. It said -"

Miss Fahnestock silenced him. "Russ, this classroom is not the place to talk about

games. We are facing a very serious moment in history."

"But, Miss Fahnestock, game theory helps you understand history."

"I have studied history for many years without finding anything about games to be

relevant, thank you, Russ. All right, Timmy, what is your news item?"

Russ swallowed his frustration, and soon forgot about it. He was surprised when

Lyn approached him in homeroom after the last bell.

"Russ," she said, "maybe Miss Fahnestock doesn't want to know what game

theory has to do with Nikita Khrushchev, but I do."

"Oh! Well, it takes some explaining. I guess she was right to cut me off. It

would have taken up too much class time."

"I have time now," she said, with a lilt in her voice.

"All right. You see, game theory was invented to study the best strategy for

simple games like tic-tac-toe. Well, no, that's not exactly right. You can figure out tictac-toe in ten minutes with a piece of paper. What I mean is, the people who developed

game theory wanted to find the best strategy for complicated games with many players.

To get a handle on the problem, they started out with simple two-player games. The

thing is, these games don't have to be children's games, with dice and tokens and things.

They don't even have to have rules. They can be about anything in life, as long as people

are competing to try to affect an outcome."

"Like a love triangle?"

He was caught short by the question. "What made you think of that? Oh, I

forgot. You're a girl. Actually, one of the examples in the book I read came from the

opera Tosca, and it was about precisely that."

"Precisely what?"

"What you said."

"Come on, now, Russy, say it out loud. It won't hurt you."

"A l-l-love triangle!" He was perfectly capable of enunciating the words, but her

persistence made him feel as if he was expected to put on a show. "Anyway, one of the

principles in game theory is to assign a number, a value, to every possible outcome.

Then you want to pick the strategy that makes your outcome highest, no matter what any

of the other players does. Well, when you do the calculations, this is what you find out:

in some cases, the best strategy you can follow is to randomize. For example, you could

flip a coin in private, and choose your move based on how the coin turns up."

"How can that be? Wouldn't the best move be the best move, regardless?"

"All right, here's an example. Suppose two people, A and B, have a bet. Each of

them goes on an errand every day at noon. It's either the bank or the post office. They

agree that if they go to the same building on a certain day, A will pay B one dollar. If

they go to different buildings, then (later on, when they meet) B will pay A one dollar.

You can see that it doesn't matter which place A chooses to go, he has a fifty-fifty chance

of winning.

"But now suppose it's not just a one-day bet. They agree to do the same thing

every day for a month. What is the best strategy for A? Obviously, it would be foolish

of him to go to the bank every day. The first couple of days, B might win or lose, but

pretty soon he'd catch on, and he would go to the bank every day, too. Or suppose A

went to the bank on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, and the post office on Tuesday and

Thursday. B would still figure out the pattern in a few days, and as soon as he knew the

pattern, he'd win every time. It would be smarter for A to flip a coin in order to decide

which building to go to. Then, no matter what B did, the chances are that they'd break

even at the end of the month. Are you with me?"

"Yes."

"All right, now let's talk about history. History is a game with billions of players,

all trying to get the best outcome they can for themselves. But it's a game that's only

played once. The best strategy for some moves may still be to randomize - to flip a coin but there won't necessarily be a long run of outcomes where your gains and losses cancel

out.

"Now, another thing you need to know about game theory is that it assumes

rational behavior on the part of each player. For the theory to be studied at all, they have

to assume that every player is doing his own calculations, and can be depended on to pick

the strategy that gives him the highest possible outcome. Do you see what that means?"

"Well, it's getting a little clearer, but - no, you'll have to explain some more."

"Let's see. How can I explain? Let's just say, for simplicity, that the world is split

up into two teams: the Free World and the Iron Curtain. Each team has a captain:

Eisenhower and Khrushchev. The captain decides on each move, although he has a

bunch of game theorists in a back office to tell him what the best move is for each

situation. The game theorists are doing all sorts of calculations, but they always assume

that the other side will act rationally. Now, Captain Khrushchev's game theorists come to

him one day and tell him, 'We've figured out the entire course of the game. It's going to

end up with our side losing.' Khrushchev would naturally ask them, 'Are you sure? What

assumptions have you made?' They say, 'That both sides will act rationally.' Khrushchev

says, 'And their team is making the same assumption?' They say, 'Yes.' Khrushchev

says, 'And their team is choosing its strategy based on that assumption?' They say, 'Yes.'"

"I see where you're going now!" Lyn exclaimed. "So Khrushchev says, 'I'll act

irrationally. That will spoil their assumption, and it might change the outcome of the

game in our favor.'"

"Right! I knew there was a mind behind those eyes of yours, Jocelyn."

"But what does that mean about the chance of a nuclear war?"

"Well, it's hard to imagine a worse outcome for the game than nuclear war. It

would be like a score of negative googolplex for both sides. Now, if my guess is right

and Khrushchev is rational but is only acting irrationally, that means he still doesn't want

to have an outcome of nuclear war. Basically, his strategy is just to keep us guessing. It's

in his best interest to make us believe that he would pull the trigger, but it's also in his

best interest not to pull it. So I guess the answer is, there could still be a nuclear war, but

Khrushchev's crazy behavior doesn't make it any more likely. I don't know if that's much

comfort to you."

"Actually, it is. Thank you, Russ. Gotta run. B'bye!"

She was gone. Russ subvocalized, "Good-bye ... God be wi' ye."

[Saturday, October 15, 1960]

October 14 was Russ's seventeenth birthday. The following day, Saturday, his

father closed up the bookstore at six o'clock. Vernon had told Russ to pick his own

birthday treat. Russ chose to go out for dinner and bowling. His father suggested eating

at The Spa.

"Naw, Dad, you never get your money's worth there."

"Don't count the cost, Russ. This is a special day."

"I'd enjoy Olson's more."

Olson's was a rustic place a few miles outside of Strafford. The tables were

covered with red-and-white checkered oilcloth. The walls and ceiling were all solid

white, and appeared ready to collapse if two people sneezed at once. The room was

brightly lit by about ten ceiling fixtures, bare bulbs with shallow white enamel shades.

The kitchen was separated from the dining room only by a low counter with a row of

stools. Russ was oblivious to the ambiance. The food was good standard fare, and the

prices were excellent. Mr. DeWitt ordered chicken fried steak.

Russ told the waitress, "And I'd like roast chicken, white meat, with applesauce

and cole slaw on the side." He would have felt shamefully libertine to have mentioned

chicken breast to a waitress.

"Well, well, well," said Mr. DeWitt. "Seventeen already. How does it feel?"

"A whole lot like sixteen, so far."

"Well, I suppose that's so. You get no new privileges or responsibilities at

seventeen; most of them come when you're eighteen. Do you feel pretty independent

these days?"

"We solipsists have to be independent." They both laughed.

Mr. DeWitt attempted to top Russ's joke. "I don't mind solipsists, as long as they

don't try to proselytize me." They laughed again, but not quite as hard. "But you're not

really a solipsist, are you, Russ?"

"No, of course not. I acknowledge the existence of the outside world, and of

other people. I just don't feel much connection to them."

"Might we say, in John Donne's terms, you feel like an island?"

"It's just that I don't criticize other people. I don't try to influence their decisions.

I let them live on their own terms. All I ask in return is that they do the same for me."

"You might be surprised how much influence you have."

Russ was sincerely incredulous. "Me? Pooh. I don't know anyone who would

want to be like me. Me, the misogynist? The weirdo? The nerd?"

"You know, there aren't too many people in this world who know who they are.

The great majority of them just follow someone else's example. So, you see, the few

people who follow only their own inner light - those people are the ones that the others

follow."

"Hnh. I pity anyone who has only my example to follow."

"Have you ever read Ibsen's Peer Gynt, Russ?"

"No."

"Try it out when you get a chance. One of its themes is the evil of independence.

The trolls are the bad guys, and their motto is, 'This above all, to thine own self be ...

sufficient.'"

"The evil of independence? I really don't see that, Dad. What's wrong with not

being a burden to anyone else?"

"Well, perhaps you're not ready for that particular truth yet. I'm not even sure I

am."

The food arrived and they dug into it. Presently, Mr. DeWitt said, "I only wish

we had a present for you to open."

"We already discussed this, Dad. I've got a good watch. I've got a good bike.

I've got a good record player. I've got all the books I could ask for, on the shelves of the

store. Wait a minute, there is one record I'd like to get."

"All right, look it up in the Schwann catalog and I'll order it for you."

As they drove to the Bowl-a-Drome, the father said, as he had for the past three

birthdays, "Russ, is there anything you need to know about the birds and the bees?"

"I have no use for that information, thank you. And if I did, you have plenty of

health books in stock. But I don't."

Two people bowling together can't have an extended conversation. While one is

bowling, the other is keeping score, and vice versa. They bowled three strings each.

When either of them got a strike, they both bounced up with unforced enthusiasm. Mr.

DeWitt especially enjoyed the physical exertion; usually the extent of his activity was to

carry boxes of books across his store.

When they got back home, the sky was thickly spread with stars. They could see

their breath by the porch light. When they had hung up their coats, Russ said, "Dad, I

love you," and gave him a hug. He realized that he was at least an inch taller than his

father now. How tall had he been the last time he hugged his father? Up to his

shoulders?

Mr. DeWitt said, "Russ, I don't know when I've had a nicer evening. I feel as if it

were my birthday."

As Vernon DeWitt lay waiting for sleep to come, he thought, "If we had such a

good time, why don't we do this more often?" As if to answer him, an image of Russ's

mother formed in his mind's eye.

[Wednesday, October 19, 1960]

The assignment in English IV was to compose sentences containing the

vocabulary words. When it was Russ's turn to recite, Mr. Thurman read off the word

"poltergeist". He pronounced it "pahl'-ter-jist". People who pick up their vocabulary

from reading rather than conversation often exhibit such gaps in their orthoepy.

Russ read off his sentence, using the correct pronunciation. "Poltergeists

constitute the principal form of spontaneous material manifestation."

Mr. Thurman said, "Aha! I see we have a Pogophile in the class. Russ, would

you let the rest of the class in on the joke?"

"Well, it's just that in one continuity in the comic strip Pogo, there was a young

pup dog who was just learning to talk. The only sentence he knew how to say was,

'Poltergeists constitute the principal form ...' - what I just said."

"Impressive, Russ. I seem to recall those cartoons appearing in the New York

Star when I was living in New York in 1950. Have you memorized the entire run of

Pogo?"

"Oh, no. There are just certain parts that stick in my mind. Besides, I've read it

more recently than 1950. It's in the first Pogo book."

"Ah! You have some Pogo books?"

"Just about all of them ... and Timothy Benk has some of the old Pogo Possum

comic books."

"How intriguing! All right, Judy, the next word is 'insinuate'."

Judy read, "The priest said to the glutton, 'in-sin-you-ate'." Laughter filled the

classroom.

"A most worthy pun!" Mr. Thurman approved. "But do you have anything more

to the point?"

"Sorry, Mr. Thurman, that's all I wrote."

After class, before Russ got out the door, Mr. Thurman asked to talk to him for a

minute. He said, "Russ, I have been avidly following Pogo in the newspapers for ten

ever-lovin' blue-eyed years." (He was quoting the title of a Pogo book.) "When the

comic books came out, I was too old for comic books and too young to appreciate Walt

Kelly. It would make me very happy to get to see them, I kid you not."

"Well, Mr. Thurman, as I said, they belong to Timothy Benk. I'll have to ask him

and see what he says."

That evening, Russ went over to Timmy's house. The front porch was wet and

chilly from the day's rain. The smaller Benk children were sitting mesmerized around the

television, which was showing "Huckleberry Hound". It was likely that when the show

was over, they would release their stored energy, so Timmy advised Russ to come with

him for a "walk 'n' talk".

"Have you finished your application to Jefferson-Wilson College yet?" asked

Russ.

"No. I'm stuck on the essay. I just don't have anything to talk about! I mean, my

grades are average, I didn't make it into the Honor Society, I don't know how well I'll do

on the SATs, I haven't won any awards, I haven't lettered in any sports ..."

"Don't worry about the SATs. We've already agreed to have some prep sessions

in my Dad's bookstore after school. You're a smart guy, Timothy."

"Is that an enantiosis?"

"Enantiosis? You've got me there."

"Enantiosis is irony. It means saying the opposite of what you really mean."

"You just proved my point." Russ marked Timmy's score in his notebook. "See,

we're smart in different ways. I just happen to be good at taking tests. You're good at

mechanical devices. What you have to do on your essay is show your area of strength.

Colleges want a variety of people with different strengths. You need to write about a few

of the projects we've done together, or maybe that you've done on your own. The model

rockets. The banked turn on the railroad layout - remember how we calculated the radius

of curvature, the slope, and the angle of bank? That would look really good on an essay."

"Will you look over my essay before I type it?"

"Sure, I'll proofread it. I can't rewrite it, but I'll mark any errors.

"Another proof that you're smart," Russ continued, "is that you like Pogo. But

that might not look so good on an essay. Oh, that reminds me. Mr. Thurman asked if he

could look at the old Pogo Possum comic books. He's a fan, too."

"He is?"

"He says he's been reading Pogo for ten years. I wouldn't have thought it of him.

The thing is, I almost didn't even want to ask you. If he doesn't give them back, there's

no way I could replace them."

"He's a teacher. Sure he's going to give them back."

"Your faith is touching. Well, it's your decision."

"Okay, he can see them. Maybe you'll get extra credit."

"Don't want it. Now, Timothy, I've been thinking about this way you have of

underrating yourself. If I remember, you said Jocelyn Marano was 'out of your league'. I

reject the concept. Either she likes you or she doesn't. Why don't you invite her to your

birthday party? Whether she says yes or no, the pressure is much less than if you asked

her for a date. I'm pretty sure she goes to parties."

"Hey, it's an idea. I'll think about it."

[Monday, October 24, 1960]

Russ had Algebra and Trigonometry for first period. One Monday, he was the

first to arrive for class. He had two math books with him which he had been reading

independently. They were paperbacks with brightly-colored covers, which set them apart

from the textbooks he carried. He set all his books down on his desk and went to the

front corner of the room to sharpen a pencil. While he was grinding away, the other

students began drifting in. Henry Passevent was the first to notice the paperbacks in

Russ's stack. He picked one up. He looked at it and whistled.

"Hey, everyone, look what Russ DeWitt has been reading."

Judy VanZandt grabbed the book out of his hand and read the title aloud. "Curves

and Their Properties! Va-va-voom!" She flipped through the pages and pretended to

read from it. "He casually placed his hand on her Cycloid. She turned to him and

caressed his Lemniscate with her moist Hyperbola. He said, 'You're such a Tractrix, my

little Witch of Agnesi!'" Each time she spoke the name of a mathematical curve, she

lowered her voice to a throaty contralto.

Henry was scrutinizing the second book by now. He yelled, "My gosh, look at

this one! He's trying to get to fourth base!" The title was Propositional Logic. A half

dozen voices at once began to comment.

"Who's he planning to proposition?"

"Russ, compute a winning line for me, won'tcha?"

"Pro-o-ove your love for me, my dear!" That was Judy.

"Logic has nothing to do with it!"

"Now we know why he's so good at figures!"

"He just wants to find a cute factor and multiply!"

Russ, still in the corner with his pencil, had turned a couple of shades of red, and

confronted his hecklers with a fierce scowl. He started to shout, "I'll prove a thing or -"

but at that moment the teacher appeared in the doorway. Silence fell on the room as a

tiger drops on a rabbit, and the students decorously found their way each to his or her

assigned place. Russ was deeply grateful for the interruption. He had known all along

that a dignified silence was his best response; only his momentary surge of irritation had

prompted him to protest. But he gave way to one more weakness. He glanced across the

classroom toward Lyn Marano. She was looking back at him. He snapped his eyes back

toward the blackboard. What was that expression she was wearing? Amusement? Pity?

Tenderness?

When school let out, Russ was reminded of the morning's frustration as he packed

up his math books. However, when he arrived at DeWitt's Books, a pleasant surprise was

there to distract him. His record had come in. His father had even gift-wrapped it, and

they opened it ceremoniously.

"Thanks, Dad! Just what I wanted! Opera highlights - Gounod's Faust, Bizet's

Carmen, Saint-Saëns's Samson et Dalila ... Can I put it on the phonograph now?"

Russ had not read the entire contents aloud. One of the selections was the

Berceuse de Jocelyn, from Benjamin Godard's only successful opera, Jocelyn. With his

usual self-control, he didn't skip straight to that cut, but played the record through from

the beginning, reading along in the liner notes. When the Berceuse came up ("Cachés

dans cet asile où Dieu nous a conduits..."), he observed that the name Jocelyn appeared

nowhere in the lyric of the aria. It was a lullaby, not a love song. Even if he sang the

whole song in front of the entire school during the Senior Day assembly, his reputation

could remain intact. There wasn't a chance in a hundred that anyone would associate it

with a specific girl. Although French was not one of Russ's accomplishments, he began

to memorize the song phonetically.

[Saturday, October 29, 1960]

"Well met, Mildred!" Connie VanZandt exclaimed, having spied the history

teacher in an aisle of the IGA grocery store.

Mildred gave a start. "Oh, it's you, Connie! This is a fortuitous encounter. I've

persuaded my younger sister Augusta to try taking instant coffee instead of ground. Now

I'm facing a bewildering range of choices. For example, what about these 'flavor buds' in

Maxwell House Coffee? Are they lumpy?"

"No, Mildred. It's just an advertising slogan. Whatever they are, they're

completely dissolved."

"And would it be the same with the 'pure coffee nectar' in Chase and Sanborn, or

is that some kind of sludge at the bottom of the cup?"

"Same deal."

"Mr. Thurman has repeatedly lauded the Chock Full o' Nuts stores he patronized

in New York City."

"I've noticed that Mr. Thurman approves of products because he uses them, not

the other way around. Anyway, Chock Full o' Nuts doesn't make an instant coffee."

[Chock Full o' Nuts' website says the instant was introduced in 1961. Other brands

available then: Nescafé, Yuban, probably Folgers and Crosse & Blackwell.]

"Ah. Well, that being the case, I may as well try the most inexpensive brand

first." Connie helped her figure out which one was the cheapest per ounce.

"I didn't realize you lived with your sister, Mildred. Have I met her?"

"I believe not. Augusta is somewhat infirm and doesn't go out often. She is sixtynine years old, and one no longer has the élan of youth at that age."

"But you called her your younger sister. Why, Mildred, you must be way past

retirement age."

"Indeed I am, my dear, but I'm not ready to call it a day yet. I believe being in

contact with those young people revitalizes me. The school board summons me every

spring, and every spring I tell them they'll just have to endure me a while longer. They

seem to find a way to do it. Oh, saints preserve us! Did you see that woman?"

It was Connie's turn to be startled and then bewildered. "What about her?"

Mildred's voice sank to a hoarse whisper. "Her skirt was so short, I could see

every inch of her knees."

"Oh, that. I'm afraid you'll have to get used to it. It's getting to be the style."

"It is my firm and settled conviction that God made the knee the ugliest part of a

woman's leg as a warning not to raise the hemline above that point."

Connie chortled.

[Friday, November 11, 1960]

[Timmy's 18th birthday party. Timmy, Russ, Mark, Mitch Johnson, Judy, Lyn,

Karen Sturgis are present. Sharon was invited but didn't make it. No couples.]

[Wednesday, November 16, 1960]

Wednesday evening, November 16, the Strafford High School Band gave its first

concert of the school year. As Connie VanZandt entered the auditorium, removing her

sensible cloth coat with black velour trim, she looked around for familiar faces. She

turned back toward her son, who was tailing close behind her. "Down that way, Frank. I

want to say hello to the Maranos."

Manny Marano rose with a grin when Connie walked up. "Greetings, young

lady," he said. "Won't you and your escort favor us with your company?" He stepped

into the aisle to let her and Frank squeeze past Emily into their seats.

When they had settled down, Connie said, "Well, Emily, I haven't seen you since

the election. You must be pleased."

"Oh, I do feel good that Senator Kennedy won. He has so much to offer the

country. A war hero, an honored author, a dynamic legislator -"

"And husband of the sexiest first lady since Dolley Madison," Manny interrupted.

"There won't be any hanky-panky in the White House with Jackie there to keep Jack

happy."

"All right, Manny, that's enough of that," his wife reproved him, whereupon he

turned to his program. Turning back to Connie, she said, "It really is nice to see you,

Connie. You've become a regular recluse since Carl...." She trailed off.

"It's all right, Emily. Since Carl died. Kicked the bucket, shuffled off this mortal

coil, passed away. But you have a false impression. I'm out and about all the time. It's

just that I'm spending my time with my clients, and when it's not them, it's my children.

A working mother doesn't have too much time for socializing."

"No, I suppose you wouldn't."

"What instrument does Lyn play now?"

"The clarinet. And Judy, what does she play?"

"She's on percussion. Not drums, but the triangle, glockenspiel, chimes, and so

on. That gives us one big advantage: she doesn't practice at home.

"While we're talking, I need to catch up on your older kids. What are they up to

now?"

"We just heard from Tony last night! He seems to be very happy in his career.

You know, he works for NBC in New York. He's a researcher. He checks facts for them

before they go on the air. And his wife Diane is so sweet over the phone. I used to worry

about daughter-in-law problems, but she's very agreeable.

"Then there's Pam. She's in the last year of her nursing program at Amherst.

She's getting good grades. Dates occasionally, but there's no one boy that stands out in

the crowd - at least that she's mentioned. But she's always been very open with me about

those things.

"It's wonderful when the oldest child is well-behaved, because that sets the tone

for the rest of them."

Connie replied, "Yes, that's certainly a big help, although they're all unique in

their own way. I'm so grateful, Emily, that Lyn and Judy are friends. I think Lyn is a

really good influence."

Frank was totally bored by now. He tugged on his mother's sleeve. "When does

it start, Mom?"

"Excuse me," she said to Emily. "Let's see, Franky. It's 7:35. It was supposed to

start five minutes ago."

"Can we go out for ice cream after?"

"We'll talk about it when the time comes. While we're waiting, why don't you

draw pictures on your program?" She gave him a pencil out of her purse and turned back

toward Emily.

"I'm going to draw maps," Frank continued. "I'm going to draw a map of Gotham

City."

"What a good idea! Now, Emily, you said that Pam tells you everything. That

must be such a comfort to you. Is Lyn the same way?"

"Well, truthfully, Connie, I don't have quite the same - oh, here we go." The

curtain had started to open, and they turned their attention to the stage.

Some high school bands are good enough that a music lover can listen to them

without too much discomfort. Strafford was not fortunate enough to have such a band.

However, not many people in the audience were listening with a critical ear. The first

part of the program consisted of simplified arrangements of tunes from Kismet, a far

remove from the original Borodin, but pleasantly melodic.

At intermission, the Maranos and VanZandts all stood up to stretch. Frank asked

if he could run and get a drink of water. Connie said, "All right, but be sure to be back

here in your seat before the second half of the concert." He climbed over the seats in

front of them, where he was able to reach the aisle without squeezing past anyone.

Connie turned once more to Emily and said, "The reason I asked whether Lyn

confides in you is a personal concern. I think Judy is a good girl. But I've been getting

little dribs and drabs that have raised, I'll just say a hint of a doubt. Since Judy and Lyn

spend a lot of time together, I was hoping - oh, shoot the bunny!"

This profane outburst was occasioned by the approach of Howard Thurman. He

came and stood in the row in front of them to talk.

"Ladies, and Mr. Marano. Isn't this lovely? You must be so proud of your

daughters. They did such a good job with Kismet. It really took me right back to 1954,

when I saw it performed on Broadway. I still have my Playbill with the Hirschfeld

illustration on the cover."

The two mothers made polite sounds. Howard prattled on for a while. Then he

said, "Connie, I have an empty seat by me. Would you like to continue the

conversation?"

"No, I can't leave this seat. Frank will be coming back here after the

intermission."

"Pity." He wandered away.

"What was that all about?" asked Emily.

"One of the minor afflictions of a widow's lot. He comes by the office once or

twice a week to have a little chat. He seems harmless enough, so I just turn my attention

level down a few notches and let him drone on. The poor chump doesn't seem to have

any family within a thousand miles, and I don't think he's made any friends here."

"You're an angel of mercy to put up with it, Connie. As for what we were talking

about, I think I see what you want. I'll see if I can't pump Lyn a bit, and if I learn

anything you should know, I'll give you a call. Oh, they're dimming the lights."

"And Franky not back yet. I'd better go hunt him down. Thank you so much,

Emily, you're a pal."

Connie found Frank walking the halls of Strafford High, yanking on one locker

padlock after another.

"What are you doing, young man?"

"Looking for a locker that's open," he replied truthfully.

"And what did you plan to do if you found one?"

"I dunno. See if I could fit inside. Look for mash notes. Stash my gum."

She rolled her eyes, at a loss to know which peccadillo to address first. "Come

on, or we'll miss the concert. And just forget about any ice cream afterward." They

reached the auditorium as the curtain was parting, so they quickly slipped into two empty

seats at the back of the room.

[We need to have some kind of follow-up where Emily reports back to Connie,

but she hasn't found out anything very substantive about Judy.]

[Saturday, December 24, 1960]

Russ was home alone on Christmas Eve. He wrapped his father's Christmas

presents and laid them under a two-foot artificial tree made of wire and green tinsel,

which sat on the coffee table in the living room. He made his supper, ate it, and washed

the dishes. Then, he indulged himself in luxury. He changed into pajamas and bathrobe;

opened a pack of Hydrox cookies; poured a glass of cold milk; put his opera highlights

record on the phonograph; and lay back on the couch with a math book.

After about twenty minutes, the phone rang. It was his father. Vernon was

keeping the bookstore open for last-minute shoppers. A lot of them were asking for gift

wrapping. As a modest form of advertisement, he had a supply of foil stickers embossed

with his business name and address. He liked to use these stickers to hold the ribbon in

place on the package. However, he had used up all the stickers on hand. There were

more sheets of them in a drawer in his desk at home. Would Russ be willing to bring

some of them uptown for him?

"Sure, Dad, but I'm already in my p.j.'s, so it will take me a while."

"Oh, I didn't realize that, son. Forget about it. I don't really need them."

"No, Dad, I don't mind. I'll be there in a half hour."

Russ looked first in the broad top drawer. He flipped through a pile of papers, but

didn't see the stickers. Next, he tried a deep drawer full of file folders. Some of the

folders clearly indicated on their tabs that they were not of interest: taxes, phone bills,

car papers, and so on. One folder said "labels", but when he pulled it out, it contained

sheets of blank labels for addressing envelopes. Then he found a folder at the back of the

drawer with nothing written on its tab. He pulled it out and looked inside.