His explanation: There exists a non-physical organizing

advertisement

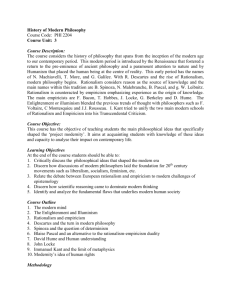

QUEEN’S UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY WELCOME TO PHL 381* PHILOSOPHY OF THE NATURAL SCIENCES Professor Joshua Mozersky 1 Administrative matters 1. Syllabus 2. Classroom respect policy 3. Late policy Tips for doing well in this course: Read each week’s material before class Attend class regularly Participate Read each essay carefully—preferably more than once 2 Philosophy Four branches of philosophy Logic: The study of reasoning. Ethics and value theory: The study of moral and aesthetic claims. Metaphysics (Ontology): The study the most general features of reality. Epistemology: The study of knowledge. 3 Philosophy and science Many of the most famous philosophers were scientists or mathematicians: Aristotle (biology, medicine, cosmology) Descartes (geometry) Leibniz (calculus) Kant (physics, geography) Russell (mathematical logic) So science and philosophy have a deep connection. Here is at least one reason why: 4 Science, knowledge and reality Science has two features of interest to the philosopher: 1. It seems to be the best means of securing knowledge. 2. Its theories seem to tell us what the world is like. So, understanding science can help us to understand the nature of knowledge and reality. 5 What is science? We are interested in: 1. Understanding the nature of science 2. Examining the impact of science on traditional philosophical questions So, we begin the course by asking: What distinguishes science from nonscience? This is a question about the methods of science rather than the answers it gives. 6 Epistemology primer What is it to know that P? Here is the traditional answer: S knows that P if and only if: 1. S believes that P 2. P is true 3. S’s belief that P is justified (S has adequate reason to believe that P) A key question for epistemology: how are beliefs justified? 7 Two traditions Rationalism Knowledge is derived from (justified by) reason not the senses. The senses may provide information for reason to use but they cannot provide knowledge themselves. E.g.: Descartes, Leibniz, and Spinoza. Empiricism These senses are the source (justification) of all knowledge. Everything we know is either observed directly or else deduced on the basis of observation. E.g. Locke, Berkeley, Hume. 8 Rationalism Rationalism may seem implausible, but consider Descartes’ example: I observe a piece of wax. It is solid, cold, scented, white. I approach the fire. The wax is now liquid, warm, scentless, clear. Every sensory property has changed! Descartes: So, if I know it is one and the same wax before and after, this knowledge cannot be delivered by the senses. Even empirical knowledge is the result of reason. 9 Rationalism and metaphysics Traditionally, rationalism has been more amenable to metaphysical speculation: If reason is our source of knowledge, then we can discover the nature of reality by examining the nature of reason. But it is hard to see how reason alone can answer these questions unless one postulates a very intimate connection between the human mind and non-mental reality. 10 Metaphysical systems There are a number of possibilities here: Solipsism: there is no reality outside the mind. Idealism: all reality is made up of ideas. There are things outside the mind, but they are just ideas in the mind of God. Kantianism: the mind constitutes external reality—what is real depends on the human mind’s activities. Cartesian rationalism: I can be certain that God exists and that God doesn’t deceive me so I can be confident that my thoughts are accurate. These systems are designed to justify the use of reason as the source of knowledge. They often involve supernatural or theological elements. But a number of scientific developments cast doubt on these approaches… 11 First example: geometry Kant was very influential. He argued that the mind imposes categories on reality that are universal and necessary. These categories include Newtonian space and time—i.e. a physics that is governed by Euclidean geometry. But, in the 19th Century, non-Euclidean geometries were developed. They were: Coherent Scientifically useful (Einstein) So the idea of universal mental categories that determine reality seemed implausible— our experience can be misleading. 12 Second example: Darwin Darwin’s theory of natural selection showed that through chance physical processes: Some traits will multiply over time Others will be eliminated Result: a system of creatures very well designed for their environment. This process was not ‘purposeful’ or ‘directed’ by God; it was simply a combination of chance and causation. Most scientists saw Darwinian (causal) explanation as superior to traditional metaphysical explanations, e.g. God. 13 Third Example: Hans Driesch He is a renowned embryologist. His experiments: The development of an embryo proceeds normally even if: The early cells are rearranged A single early cell is isolated His conclusion: Neither spatiotemporal location nor physical mass is relevant to the development of the embryo. His explanation: There exists a non-physical organizing principle—an entelechy—that guides the development of living things. Entelechies impinge on the spatiotemporal world, but have no quantitative features so they can’t be measured. They can only be known by reflection on empirical results. 14 Science vs. non-science Philosophers came to think that postulations such as entelechies were ‘occult’ entities that had no place in science. Explanations should be more like Darwin’s. They already had some idea as to what counted as science and what didn’t: Science Physics Biology Chemistry Astronomy Etc. Non-science Theology Entelechy Alchemy Astrology Etc. Still, it would be nice if we could determine a principle that captures what is distinctive about science… Stay tuned, more is coming next week! 15