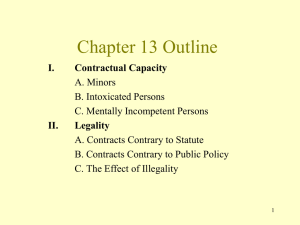

CONTRACTUAL CAPACITY

advertisement

CONTRACTUAL CAPACITY INTRODUCTION As previously noted in the chapter on Introduction to Contracts, "contractual capacity" is a necessary element of a contract. The concept of capacity means that an individual has sufficient understanding in the eyes of the law to protect himself in the marketplace. The rules on capacity been have created to protect people who were believed to lack such an understanding. Historically, the eyes of the law had very narrow vision indeed, and only the privileged few--the lords of feudal England--had full capacity to contract. Today, capacity to contract is presumed, and questions concerning lack of capacity are confined to three major areas: (1)minority; (2) insanity; (3) and voluntary intoxication. Since capacity to contract is presumed, any lack of capacity must be asserted and proven by the person claiming lack of capacity as a defense to the enforcement of a contract. Case 1: Louie Lush, more than slightly intoxicated,passes by Veronica's Exotic Pet Store one afternoon and spies an animal in the window. Believing the animal tube a hamster with a glandular condition, Louie buys the"critter" and takes it home. He is rudely awakened in the middle of the night with a crash as his new pet beaver eats through his wooden bedpost. Should Louie attempt to avoid his contract for the purchase of the beaver, he would have the burden of asserting and proving that he was so intoxicated he lacked the capacity to contract. Generally, if lack of capacity is proven, the effect is to make the contract voidable at the option of the party who entered the contract under the lack of capacity. An exception is made in the case of people who enter contracts after they have been adjudged insane; their contracts are absolutely void. 1 Case 2A: Duey Dingbat, believing himself to be Napoleon, purchases a horse on which he intends to ride to war. If Duey can prove that his delusion so affected him that he did not understand the nature of the contract he had entered into, the contract to purchase the horse would be voidable at Duey's option. NOTE: The seller of the horse could not have the contract set aside on the basis of Duey's insanity--this right to avoid the contract belongs solely to the person under the disability. Case 2B: Assuming the same facts except that Duey had been judicially declared insane prior to his purchase of the horse. If that were the case, either party could prove the judicial declaration and have the contract declared void. MINORS INTRODUCTION At common law, in order to protect minors from being taken advantage of in the marketplace, full capacity to contract was withheld from minors (also termed "infants" in legal literature) until the age of 21. Today, most states have established 18 as the age at which minors obtain full capacity to contract. Except where prohibited by statute, minors have the right to avoid their contracts. This right is called a minor's right to disaffirm. By providing minors with the right to disaffirm contracts in order to protect them from their mistakes, the law has also created a burden in that many people will not deal with minors. The special status of minors in the law leads to the following questions which will be discussed below: 1. What is the nature of a minor's right to disaffirm contracts? 2. How may a minor become bound on a contract? 3. What are the obligations of a minor upon disaffirmance? 4. What are the other party's obligations upon disaffirmance by the minor? 5. What obligations can not be avoided by a minor? 6. Does a misrepresentation of age effect a minor's right to disaffirm? 2 7. Under what circumstances are parents liable for the conduct of their minor children? DISAFFIRMANCE--A MINOR'S RIGHT TO AVOID CONTRACTS Generally, a minor may disaffirm his contracts at anytime during minority or within a reasonable time after reaching majority. One exception is contracts for the sale of land which a minor may not disaffirm until after reaching majority. Other exceptions exist by way of statutes which prohibit the disaffirmance of certain types of contracts, e.g., most states prohibit the disaffirmance of student loans extended by the state. A disaffirmance is a manifestation made by the minor, either expressly or by implication from his conduct, of an intention not to be bound by the contract. Case 3A: Jon Revolta, a minor, had hopes of becoming a great "disco" king, so he went to a jewelry store and purchased a gold medallion necklace for $2,000. After a week of constant responses at the "disco" such as "Buzz off, Turkey", Jon decided that being a "disco" king required more than a gold medallion, and that he had wasted $2,000. Jon went to the jeweler, demanded his money back, and tendered back the necklace. This act by Jon constitutes an express disaffirmance. Case 3B: Suzie Sluffoff, a minor, entered into a contract to work as a telephone solicitor for a week. On the day she was to begin work, Suzie awoke to find that it was a beautiful day for going to the beach. She decided she would much rather spend the week getting a tan than speaking to people she didn't know over the telephone, so she never reported for work that week. As Suzie failed to show up for work, this conduct would indicate an intention not to be bound--a disaffirmance implied by conduct. As disaffirmance is permitted within a reasonable time after the minor reaches majority, how is one to know what constitutes a reasonable time? The question of what is a reasonable time is a question of fact to be determined by the trier of fact (the 3 jury or the judge if the case is tried without a jury) upon an examination of all of the circumstances which surround the transaction. Like many legal principles containing the term "reasonable", this last principle provides little guidance to the student for problem solving purposes. Here are some guidelines which can be considered in solving a "reasonable time after reaching majority" problem: 1. The intelligence of the minor with regard to business matters. A minor who operates a business will be given Leslie than a minor with little or no business experience. 2. The subject matter of the contract. If the subject matter of the contract is a highly depreciable asset, such as a new car, a minor would be given less time to disaffirm than if the item were one that would maintain its value, such as land. 3. The injury that would result to the other party if the contract were disaffirmed. A minor who has wrecked the motorcycle he purchased would find less sympathy in court than one that could return the motorcycle in working condition. 4. The extent to which the contract was fair. Where the evidence indicates that the adult took advantage of the inexperience of the minor, say, by charging a price that was grossly out of proportion to the market value of the item sold, the court is likely to be more generous on the question of time to disaffirm. 5. Whether the contract has been executed or still remains executory. If neither of the parties has performed any duties under the contract, it is likely that the court will be more lenient on the question of time than where some or all of the duties under the contract have been executed. As noted, the above items are only guidelines. No one factor alone would ordinarily be determinative. In the event the evidence is insufficient to establish that the minor disaffirmed the contract within the "reasonable time after reaching majority" criteria, he will be held to be bound to the contract. It will be held that the minor has ratified the contract. RATIFICATION--HOW A MINOR MAY BECOME BOUND ON A CONTRACT As disaffirmance is a manifestation of intent not to be bound, ratification is the 4 opposite: a manifestation of intent to be bound. Ratification must occur after the minor reaches majority; however, like a disaffirmance, a ratification may be either express or implied. The most common way for a person who has reached majority to ratify a contract made during minority is to fail to disaffirm the contract within a reasonable time after reaching majority. Often such a ratification by conduct is more "legal" than"actual" in that the new "adult" generally is not aware of his right to disaffirm. Case 4: Sloto Catchon purchased a new car on an installment contract when he was seventeen. After he reached eighteen, the age of majority, he continued to use the car and make payments on it for six months. Shortly thereafter, he enrolled in a Business Law course and learned that he had the right to disaffirm contracts he had made as a minor. Unfortunately for Sloto, by the time he learned he had the right to disaffirm, it was too late to exercise that right as he had ratified the contract by conduct through the continued use of the car and the making of payments on the installment contract. A minor upon reaching majority may, of course, expressly ratify a contract made during minority. If, for example, a minor had purchased land which had increased in value, he would be well advised to expressly ratify the contract of sale upon reaching majority. Another manner in which a minor's contract may be held to be ratified is by estoppel. This means that the minor acted in such a way that a disaffirmance would have the effect of taking advantage of the other party, therefore, the court would hold that the new adult could not disaffirm--he would be estopped from doing so. Case 5: Simon Sharpie sold land to Tom Trusting while Simon was a minor. After reaching majority, Simon would go by the property and watch Tom building a house on it. As soon as the house was completed, Simon notified Tom of his intention to disaffirm. Even if Simon's expressed disaffirmance were made within a reasonable time of his reaching majority, the court would hold that he was estopped from doing 5 so and had ratified the contract. A MINOR'S OBLIGATIONS UPON DISAFFIRMANCE--DUTY OF RESTORATION The majority rule in this country is that a minor need only return to the other party the consideration if it is still in the minor's possession. Additionally, the minor is generally not liable for any damage to the consideration or loss in value due to depreciation. Case 6: Lindy Crash, a minor, buys a new hang-glider. After he finds both himself and the glider slightly crumpled at the bottom of a cliff, Lindy decides to disaffirm the purchase. Lindy, upon disaffirmance, need only return the crumpled glider; he would be liable for neither the damage nor normal wear and tear. If the minor has sold the consideration given by the other party, he must, upon disaffirmance, return the remainder of any of the proceeds that are still in his possession. However, if the consideration was lost, destroyed, or given away, the minor need not return anything. Case 7A: Tinear Sniffel, a minor, purchased a new stereo for $750.00. After listening to it for a week, he decided he didn't like it, so he sold it to his friend Harry for $500.00. Two weeks later Tinear learned that he could disaffirm his purchase of the stereo, and he notified the stereo store of his intention to disaffirm, demanding the return of his purchase price. The fact that Tinear no longer has the stereo will not prevent him from disaffirming; however, if he still has any of the $500.00 he received from Harry, the amount of his purchase price returnable to him will be reduced by the amount of Harry's money still in his possession. Case 7B: Assuming the same facts as above except that Tinear got angry with the stereo and ran over it with a truck. Under those circumstances, Tinear need not return anything and he is not liable for the destruction of the stereo. 6 In some states the above general rule has been modified either by statute or court decision. In these minority jurisdictions, a minor must restore the consideration received or its value before disaffirmance is permitted. The Supreme Court of Oregon, for example, has held that a minor must pay depreciation on an automobile before being permitted to disaffirm. THE OTHER PARTY'S OBLIGATIONS UPON DISAFFIRMANCE BY THE MINOR When a minor disaffirms a contract, the other party to the contract is obligated to restore to the minor any consideration given by the minor, or if that is not possible, its value. Case 8: Willie Wiseacre, a minor, purchased for cash a Schloose 10 speed bicycle from Trusting Bicycle Shop. He rode the bike all summer, and with winter coming on, he decided to disaffirm the purchase. When Willie disaffirms, the bicycle store must return the purchase price. NOTE: After reading this and the preceding section, many students daydream about what they could have "gotten away with" as a minor. Before these daydreams overtake you, be aware that it is precisely because of these reasons that many merchants will not do business with minors. Prior to the enactment of the U.C.C., if the other party had sold the consideration received from the minor to a third party before the minor's decision to disaffirm, the minor could legally obtain the consideration from such third party. This rule has been modified by Section 2-403 of the Code. Under 2-403, a person with voidable title to goods (such as an adult that has dealt with a minor) may transfer good title to a good faith purchaser for value. Thus, if an adult purchases goods from a minor and then sells them to a third party who has no knowledge of the transaction with the minor, when the minor disaffirms, he can not obtain possession of the goods from the third party. The adult, however, will be liable to the minor for the value of 7 the goods. Case 9A: Speedo Rev, a minor, sells his 1965 Mustang to Fasttalking Fredy's Used Cars for $750.00. Speedo comes home to find that someone has offered him $1500.00 for the car and decides to disaffirm the purchase. Upon returning to Fredy's he discovers that Fredy has sold the car to Glenda Gern, a good faith purchaser. Speedo will not be able to recover possession of the car from Glenda. Case 9B: Assume the same facts as above except that Fredy gave the car to his son as a gift. Speedo could recover possession of the car from Fredy's son as there has been no sale to a good faith purchaser. OBLIGATIONS A MINOR MAY NOT AVOID Although the protection afforded minors will ordinarily permit them to avoid their contractual obligations, there are two classes of obligations that minors may not avoid. These are: (1) the obligation to pay the reasonable value of necessaries furnished them; and (2) the obligation to pay for their torts. LIABILITY FOR NECESSARIES A minor is liable for the reasonable value of necessaries he purchases. This liability is not based on the contract, which like other contracts may be avoided by the minor, but instead rests in quasi-contract. Quasi-contract liability promotes justice because the minor needs the item and the supplier can only receive the reasonable value as opposed to the contract price, thus neither party can be taken advantage of. By now you must be curious about what is meant by the word "necessaries". Well, necessaries include food, clothing, shelter, medical care, educational services, and similar items which are appropriate to the station in life of the minor in question. Just what is a necessary as to a particular minor depends on the socio-economic status of the minor. If the goods or services furnished a particular minor are necessaries as to him there is liability; if they are luxuries, there is no liability. 8 Case 10A: Prudance Prim went to Sak's Fifth Avenue to purchase a dress for her "coming out" sixteenth birthday party. It was to be a rather quaint affair as only her closest 250 friends were invited. She picked out a $500.00 dress and paid for it out of her small change purse. If Prudance decided to disaffirm this purchase, she would still be liable for the reasonable value of the dress (which may or may not be $500.00) as the dress is commensurate with her station in life. Case 10b: Assume that it was Hollie Hihopes, an orphaned minor working as a stock girl, who used her last $500.00 to purchase the dress. In that case, Hollie could disaffirm the contract for the purchase of the luxury item without liability. NOTE: Students frequently experience difficulty with this built in discrimination in the law of necessaries. To help keep this clear, remember that the word necessary is a term of art which varies with each minor whereas what is a necessity for survival tends to be rather uniform for everyone. In modern times there has been a tendency to expand the concept of necessaries. This trend was promoted by the desire of courts to prevent injustices to adults who provided goods and services to older minors which were traditionally not regarded as necessaries but which had become important to older minors under modern economic conditions. Perhaps this trend will stop now that the age of majority is 18 rather than 21 as it was under common law. Today, such items as tools of the trade, an automobile used in business activities, a vocational education , and two years of college are likely to be regarded as necessaries for most minors. MINORS' TORT LIABILITY Generally, minors are liable for their torts. An exception to this general rule is that minors are not liable for their torts which arise out of a voidable contract. Case 11A: Willie Rachet, a minor, operates an automobile repair shop. One day, Dwarg Farquat brings his new Porsche into Willie's for a tune up and oil change. After finishing the oil change, Willie forgets to tighten the oil drain plug. Needless to say, the oil drains out and Dwarg's engine is destroyed. Dwarg sues Willie in tort for Willie's negligence in working on the car. Willie will not be liable to Dwarg in tort as Willie's negligence arises directly out of his contract to repair the car which would generally be 9 voidable. NOTE: Some states by statute prohibit minors from disaffirming contracts regarding businesses they own and operate. In such a state Willie's repair contract would not be voidable and he would be liable to Dwarg in tort. Case 11B: Assume the same repair contract as above except that Willie is sued in tort because he drove the Porsche into an embankment while "joyriding" in the car after the repairs were completed. In that case Willie would be liable in tort because his negligence did not have to do with the contract but was an independent act. THE EFFECT OF A MINOR'S MISREPRESENTATION OF AGE Generally, a minor's misrepresentation that he is above the age of minority will not prevent the minor from disaffirming a contract. Beyond this majority application of the general rule on disaffirmance, the legal waters get quite muddy when a minor's misrepresentation of age is involved. In a few states statutes have been enacted which prohibit disaffirmance by a minor where there has been a misrepresentation of age. Another small minority of states prohibit disaffirmance on the basis of equitable estoppel established by way of court decisions. Even in the majority of states which permit disaffirmance, a minor who misrepresents his age in order to induce an adult to enter into a contract, can not escape without liability. Many of these states permit the minor to be sued for the tort of fraud on the basis of the misrepresentation. The theory here being that the tort is independent of the contract, and that minors are liable for their torts. In these states, the adult can also raise the minor's fraud as a defense to a suit by the minor for breach of contract. (Personally, I disagree with this approach because I can not accept that the minor's misrepresentation of age is independent of the formation of the contract itself.) The remainder of these states, either by statute or court decision, require the misrepresenting minor to make full restitution to the adult in order to be able to disaffirm. 10 PARENTAL LIABILITY FOR THE CONDUCT OF THEIR MINOR CHILDREN The possibility of parental liability for the conduct of their minor children arises in three areas: (1) liability for their children' contracts; (2) liability for necessaries furnished their children; and (3) liability for their children's torts. Contractual Liability Generally, parents have no liability on the contracts made by their minor children. A parent may become individually liable by co-signing a contract with is minor child or by entering into an agreement to guarantee his child's contractual performance; however, in these cases liability is not based on the position of parent but upon the parent's own contractual promise. Liability for Necessaries A parent is not liable for necessaries furnished his minor child unless the parent has failed to provide such necessaries. Case 12A: Purcy Particular, a minor, comes home to find his mother has made her specialty "Hawaiian Hash" for supper. Purcy informs his mother that one more meal of that "junk" will cause his early demise and that he is going out to eat instead. Purcy goes to the local Burger Prince and fills up on burgers. If Purcy should decide to disaffirm the purchase of the meal at Burger Prince, his parents would not be liable for the reasonable value of the meal because they had provided him with necessaries (Purcy would be liable for the reasonable value of the meal, however). Case 12B: Assume that when Purcy came home and asked what was for dinner his mother said: "You're not going to get another meal here until you go out and get a job". If the rest of the facts were the same, Purcy's parents would be liable for the reasonable value of the meal at Burger Prince because they had failed to provide him with the necessary in question. Parental Liability For The Torts Of Their Children. 11 Contrary to popular belief and the statements of parents which are designed to keep their children on the "straight and narrow", parents are not liable for the torts of their minor children simply on the basis of their parentage. A parent may become liable for the tort of a minor child under the ordinary rules of negligence in any of the following circumstances: (1) Where the parent entrusts the minor with a dangerous instrumentality that the child does not possess the maturity to use properly (Many cases where playmates are shot with BB guns proceed on this theory.); (2) Where the parent is aware of dangerous conduct of the minor child and fails to control the child so as to prevent injury to others (I once represented a five year old girl that was nearly burned to death by a seven year old boy who had the habit of trying to kill his playmates.); (3) Where a child's tort is committed while the child is acting as the agent or servant of the parent (In this category is what is called the "family purpose doctrine" which covers such circumstances as a child running over a little old lady on his bike while on the way to pick up bread for the family at the grocery store.); and, (4) Where the parent directs, condones, or sanctions the tort (Cases of this type may take place when little Jonnie comes home any says: Fredy said you're a jerk", and Jonnie's Father responds: "Go beat the turkey up."). INSANITY AND INTOXICATION INTRODUCTION 12 The rules regarding lack of capacity due to insanity or intoxication are quite similar to the rules on minority. Of course, proving insanity or intoxication is much more difficult than proving age. What must be proven in order to establish lack of capacity on the basis of insanity or intoxication is that at the time of the making of the contract, the person claiming lack of capacity was so insane or intoxicated that he did not comprehend the nature and purpose of the contract. Once lack of capacity on the basis of either insanity or intoxication is established, the contract is voidable at the option of the person who has proven his disability. NOTE: The exception to this last rule, as mentioned at the beginning of the chapter, is for people who make contracts after they have been judicially declared insane; their contracts are absolutely void. The similarities and differences between the rules on minority and insanity or intoxication will be explored below. DISAFFIRMANCE Disaffirmance is basically the same with insanity or intoxication as it is with minority, however, some states do not recognize the right to disaffirm on the basis of intoxication. Additionally, in those jurisdictions which permit disaffirmance on the basis of intoxication, the person claiming lack of capacity must also show that the contract was not a fair bargain; that he was taken advantage of because of his condition. Disaffirmance on the basis of insanity may be made by the person himself if the insanity has been cured, or by his representative if after the making of the contract he has been judicially declared insane or died. RATIFICATION As with minority, a contract may be ratified once the infirmity is no longer present, and failure to disaffirm within a reasonable time after regaining sobriety or sanity will constitute a ratification. With insanity, ratification may be expressly made by the insane person's legal representative subsequent to an adjudication of insanity or death. 13 DUTY OF RESTORATION Intoxicated persons are always required to make full restoration upon disaffirmance. With insane persons, full restoration must be made if the contract was fair and the other party did not know, either actually or on the basis of the circumstances, of the insanity. If the contract is unfair or the other party knew or should have known of the insanity, the insane person need only return what consideration remains in his possession as is the case with minors. OTHER PARTY'S OBLIGATIONS UPON DISAFFIRMANCE The principles are the same with regard to insanity or intoxication as they are with minority. If the insane or intoxicated person has performed all the duties necessary to disaffirm, the other party must make full restoration. LIABILITY FOR NECESSARIES Both insane and intoxicated persons are liable for the reasonable value of necessaries provided them. 14