Contracts Outline

advertisement

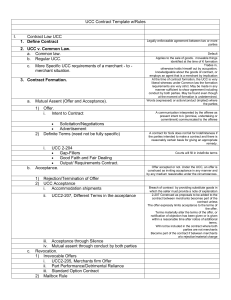

Contracts Outline Printed: March 6, 2016 I. Challenge of an ideal contracting system. A. Must clearly assign all risks between the parties, including: 1. Non-performance 2. Late performance 3. Unacceptable performance 4. Early performance 5. Change in specifications 6. Acts of God 7. Unexpected costs 8. Diminished revenues 9. Market forces B. Must provide remedies for violations of the contract. 1. Short of specifically identifying all risks, the contracting parties can avoid litigation of unforeseen risks by providing clauses to handle unforeseen developments as they arise. C. In short, it must regulate risk distribution. II. Nature and Extent of pre-contractual risk A. Cannot avoid pre-contractual inherent risks by simply not contracting. B. Can only shift burdens of risk between parties. C. Contracts do not create the pre-contractual risk. D. Parties can contract with regard to risks they have no control over, however absurd or improbable. (Anderson v. Backlund: can contract that it will rain). III. Reservation of Power A. Reservation of power to terminate a contract at any time. 1. "Termination of a contract by one party except on the happening of an agreed event requires that reasonable notification be received by the other party and an agreement dispensing with notification is invalid if its operation would be unconscionable."UCC §2-309(3). a. In Sylvan Crest, gov't can't arbitrarily terminate the contract because they saw a better opportunity, even if they give themselves explicit power to do so. 2. In Mabley v. Borden, company can't retract an offer after it has been reasonably relied upon, even though they give themselves explicit power to do so. B. Reservation of power to terminate upon failure to contract concerning additional terms in the future. 1. "A contract is not renedered void because the parties thereto contract or agree to contrat concerning additional matters." Borg Warner. 2. "[T]he fact that some matters are left for future agreement among the parties" does not mean that they have not already contracted. Itek. C. Reservation to determine the extent of one's own performance 1. Davis v. General Foods, the company cannot "speak out of both sides of its mouth" and encourage the performance of the other party (providing Roger W. Martin 1 Contracts Outline Printed: March 6, 2016 the recipe) while explicitly stating that they are to determine the extent of their own performance (payment). D. The law is deliberately "fuzzy" so as to encourage ethical business practices. 1. The courts realize that parties need some room to wiggle. 2. The more carefully you equivocate, the more likely you are to have reasonably convinced the other party that you have committed, and thus bind yourself. 3. There is no amount of explicitness that places you squarely within the 'zone of safety" if you are acting in bad faith, or the risk distribution is too lopsided. IV. Implied-in-Law Contract (Quasi-Contracts) A. A complete fiction, constructed by the courts to prevent unjust enrichment of one party at the expense of another. A contract implied by the nature of the surrounding circumstances, even though neither party may have desired to contract. 1. A doctor will get payment from an unconcious emergency patient, even though the patient cannot "consent", and even thought the patient later dies, because the law must encourage people to assist helpless victims. An injured person is implied by law to assent to treatment to save him. Cotnam v. Wisdom. 2. Fire services provided to the wrong district. Upton v. Powell. B. The amount of recovery due to the unjust enrichment is the fair market value of the materials or service provided. 1. The court constructed an implied-in-law contract in Vickery v. Ritchie, when the architect bailed after misrepresenting the price to both sides. The court constructed the contract because the bath house had been built, and therefore ∆ was unjustly enriched. The amount of the recovery was the fair market value of the services, even though the overall value of the property had gone down. V. Remedies (overview) A. π has conferred some value upon the ∆ in reliance on the promise of the ∆ and the ∆ fails to perform. 1. Court may force ∆ to pay for the value he received from π. 2. Restitution Interest - Prevention of "unjust enrichment". a. reliance by the promisee b. resultant gain by the promisor c. strongest case for court remedy B. π has changed his position upon reliance on the promise of the ∆ (e.g. committed some resources, passed on other opportunities) 1. The court may force ∆ to pay to put π back in the condition he was in prior to commiting resources. 2. Reliance Interest Roger W. Martin 2 Contracts Outline Printed: March 6, 2016 a. broader in scope than the restitution interest, which is a special case. b. covers "losses caused" and "gains prevented" 3. Ex: π tears down buildings in reliance on ∆'s promise to provide financing for a high rise. Wheeler v. White. C. ∆ has not fulfilled a promise upon which the π reasonably expected to be performed. 1. Court may either require promise be fulfilled, or put the π in as good a position as he would have been in the promise were made good. 2. Expectation Interest a. distributive justice, meaning does not seek to re-establish status-quo, but rather establish a new status. b. court assumes an active role. 3. Ex: failed negotiations were constructed by the courts so that a prospective shopping center tenant could move in at a reasonable rate after they had provided a critical service for the builder. City Stores v. Ammerman. VI. Types of Contract Theories (overview) A. Express Contract 1. Terms of negotiation have been set forth in words (oral or written) in such a way that there is a reasonable belief that a commitment exists. 2. Expectation interest protected; "benefit of the bargain". B. Implied-in-Fact Contract 1. same as express contract, except the words are not spoken or written. Only the medium of expression is different (conduct instead of words). 2. Expectation interest protected; "benefit of the bargain" 3. More difficult burden of proof than express contract. a. Familial relations (husband and wife in Hewitt, and father/son in Hertzog) make courts reluctant to find enforceable transaction. C. Quasi-Contract 1. created and imposed by the courts to prevent unjust enrichment. 2. Restitution interest protected D. Promissory Estoppel §90 of the Restatement 1. offeror makes a promise that could reasonably induce an act or forebearance on the part of the offeree, and the offeree is actually induced by that promise. 2. Specifically designed to protect the Reliance interest, but could get you to Expectation interest if the court wishes to encourage litigation by providing a large reward. VII. Indefinite Wording of Contracts A. Most indefinite phrases are used as reservations of power to allow the party to escape to more lucrative deals. B. Performance of one of the parties is left unspecified. Roger W. Martin 3 Contracts Outline Printed: March 6, 2016 1. "An agreement for sale which is otherwise sufficiently definite to be a contract is not made invalid by the fact that it leaves particulars of performance to be specified by one of the parties." UCC §2-311. a. Ex: Moulton v. Kershaw and Fairmount Glass where the "offer letter" did not specify an amount. C. Error in the communications most likely to be construed against drafter. 1. U.S. v. Braunstein, there was a clerical error in the price sent on the telegram and buyer tried to take advantage of the error to exit the bargain. D. Silence can be viewed as assent when the silence is relied upon by the other party. 1. Ex: Cole-McIntyre the salesman accepted the order, but did not ever tell the buyer that it would not be filled. Based on the nature of the business and the previous relationship of the parties, the buyer reasonably relied on the seller's silence as acceptance of the purchase order. 2. UCC §2-204 specifies that a "contract for sale of goods may be made in any manner sufficient to show agreement", which includes silence if the facts fit, even if the precise moment of contractual commitment is unknowable. VIII. The Reliance Principle A. The principle that protects the offeree when the offeror unreasonably misled the offeree, and the offeree was reasonably misled. 1. Any promise that the offeree can reasonably rely on, even if there appears to be no consideration. 2. Ex: Seigel v. Spear, where the π relied on the ∆ to insure his furniture, and so the π forewent getting insurance of his own. B. Material discrepancies between the seller's and the buyer's language. 1. "Battle of the forms" where both parties attempt to make conflicting reservations of power, and the "offer" and "acceptance" do not mirror eachother. 2. Regulated by UCC §2-207 which states that additional terms in an acceptance or a confirmation are to be proposals which become part of the contract unless they materially alter it, or they are objected to within a reasonable time. 3. Examples of terms that would be thrown out are broad reservations of power contrary to custom. a. Substantial reduction of a customary warranty b. Substantial limitation of a customary remedy 4. Examples of terms left in are slight reservations of power not contrary to custom. a. Slight limitation of remedy b. Exemption of liability for some causes beyond the seller's control. 5. Direct conflicts in the language "cancel" each other out. Roger W. Martin 4 Contracts Outline Printed: March 6, 2016 C. An offeree can rely on the notion that there is no adverse language in the contract. 1. Capital Savings, where the mortgage amount was incorrectly calculated, and the buyer relied on the bank to provide an accurate figure for his monthly payment. IX. Consideration Doctrine A. Consideration is a relationship as between two parties; it is the identification and redistribution of pre-contractual risks. B. Consideration allows recovery of the expectation damages. X. Offer and Acceptance A. The offeror has the power of revocation, the offeree has the power of acceptance. A revocation extinguishes the power of acceptance, the acceptance extinguishes the power of revocation. B. Offer and acceptance problems arise when the parties are negotiating at a distance. C. Offers can end by: 1. Acceptance 2. Revocation a. occurs only when the offeree has actual notice of revocation before acceptance. 3. Lapse D. An option is an irrevocable offer that is created out of the reliance principle. 1. A sub-contractor cannot revoke his offer if it has been used by a general in the figuring of a general bid for award of a general contract. Drennan v. Star Paving Co.. It becomes an option at the time the bids are opened, and binding upon award of the contract. 2. The general can not "bid shop" for a different sub after he has used the sub's bid in a general bid. So. Cal. Acoustics. 3. UCC §2-205, an offer is not revocable, for lack of consideration, for the time stated by the offeror, or if no time is stated, for a reasonable time. E. An acceptance by mail is effective upon "dispatch" instead of actual receipt because it protects the offeree's reliance. F. To be an offer, a statement must reasonably convey a power of acceptance upon the offeree, identify the pre-contractual risk, and propose a way to re-distribute that risk. 1. An offer of reward conveys a power of acceptance upon the general public. Smoke Ball. G. UCC §2-206- Unless otherwise stated, an offer can be accepted in any manner reasonable under the circumstances (promise or performance). Davis v. Jacoby where a promise to perform was held to be sufficient acceptance during the lifetime of the offeror. Roger W. Martin 5 Contracts Outline Printed: March 6, 2016 1. Where the offer invites acceptance be performance, the beginning of performance transforms the offer into an option, and the option becomes binding upon complete performance. Restatement (Second) §45. Crook v. Cowan, where the court held that delivery of the carpets was sufficient acceptance to make the contract binding. 2. Unilateral contract is created by acceptance by performance, Bilateral contract is created by acceptance by promise. XI. Requirements Contracts and Output Contracts A. Requirement Contract - seller promises to sell the buyer as much as the buyer requires over a certain time period. 1. Buyer's advantages a. assures a supply b. protection against rise in prices (may get discount) c. enables long-term planning d. eliminates need for storage 2. Seller's advantages a. reduction in selling expenses b. protection against price fluctuations c. predictable market 3. Risk of non-disposal (too much supply) or increasing needs (too little supply) is borne by seller. B. Output Contract - buyer promises to buy a fixed amount from seller over a certain period of time. 1. Same advantages for both buyer and seller 2. Risk of non-disposal (too much supply) or increasing needs (too little supply) is borne by buyer. C. UCC §2-306(1) states that the buyer is required to purchase his good faith requirements from the seller, except that no unreasonable quantity (too high) can be ordered. 1. This puts bounds on the amount of lopsidedness of risk that can be redistributed, which must be balanced with the parties freedom to negotiate as they wish. 2. Normal business practices and variations in the amount of the requirements are not violations of good faith. Eastern Airlines v. Gulf where the practice of fuel freighting was seen to be part of the identified risks inherent in the airline business. D. UCC §2-306(2) states that where parties decide to deal exclusively, an obligation is imposed for the seller to use best efforts to supply the goods and the buyer to use best efforts to promote their sale. E. The courts have a great deal of power to dissovle, enforce, partly enforce, or reconstruct requirements contracts. 1. The courts prefer to find a contract so that they can regulate the parties within that framework. Roger W. Martin 6 Contracts Outline Printed: March 6, 2016 2. The court can read good faith into a contract so as to reconstruct the risk distribution, and impute the new meaning to the parties' desires. XII. "Gratuitous Promise" A. Any act or forebearance, no matter how slight, induced by the promise of an offeror is sufficient to find consideration and form a complete bilateral contract (and get the expectation interest). 1. The effort of moving a distance to perform a service is sufficient consideration. Davis v. Jacoby, Kirksey v. Kirksey. B. The risks sought to be redistributed may be vicarious, or intangible because they bring about the happiness of the parties, or of a third person. 1. In Hamer v. Sidway, the nephew's act was to refrain from using tobacco or drinking. Although this action benefitted himself directly, it was also of vicarious benefit to the uncle. 2. In Allegheny College, the woman's risk that she wished to redistribute was the possibility that she would not be remembered after her death. I. Unconscionability A. Equivalence of bargaining power is not required. Otherwise most promises would be unenforceable, and the court would lose regulatory power. B. UCC 2-302 Unconcscionability 1. The court may refuse to enforce the entire contract, enforce only the equitable portions, or limit the unconscionable portion to make the risk less lopsided. a. This allows the courts to regulate the parties within the framework of the consideration, by limiting the power of the unconscionable clause while salvaging the rest. 2. The basic test is whether, in the light of the general commercial background and the commercial needs of the particular trade or case, the clauses involved are so one-sided as to be unconscionable under the circumstances existing at the time of the making of the contract. a. This allows the parties the freedom to reserve power according to normal business practices, without allowing them to disturb the allocation of risk due to superior bargaining power. C. Fraud, duress, mistake, and unconscionability are all difficult defenses to sustain, particularly because the "mandatoriness" of the consideration doctrine requires that the contract be indifferent to the bargaining power up to the point where it interferes with the risk distribution. 1. "Fraud" implies that there was a bad-faith withholding of critical information that prevented the risks from being distributed. 2. However, it is not just any old withholding of information that prevents a contract from being enforceable. Just because one side makes a huge profit does not mean that the bargain should have been unenforceable. Roger W. Martin 7 Contracts Outline Printed: March 6, 2016 II. Modifications A. A "new" consideration is not required. If both parties decide to supersede the pre-existing contract, then an evolving consideration allows them to do so. 1. A party may feel that he needs to renegotiate a pre-existing contract to redistribute the pre-contractual risks differently in view of changing market conditions, especially risks associated with the other party's potential breach. a. Ex: an employer may promise to give an employee a raise even though the employee is already under contract for a term at a lower wage if the employer feels it necessary to recontract with respect to the risk of the employee breaching. The promise becomes binding if the employee has relied upon it to remain in the employer's service. b. Counter Ex: However, the contract modification must be in good faith, and not forced by fraud or economic duress because this would violate the consideration doctrine. 2. Changing market conditions which would cause the party seeking modification to operate at a loss are sufficient justification for modification, and are not in bad faith. (UCC 2-209). B. UCC 2-209 (4,5) states that a party may waive an executory portion of a contract, but may later unilaterally retract that waiver by giving actual notice and demand full performance if the other party has not materially changed his position in reasonable reliance upon continuance of the waiver. 1. UCC 2-209 (5) invokes the reliance principle to protect the performing party's reliance by requiring actual notice of retraction of the waiver, as well as disallowing retraction when he has materially changed his position in reasonable reliance. a. Ex: reduction in rent for a period of one year can not be retracted during that year by the owner claiming that it was a gratuitous promise. 2. UCC 2-209 (5) also invokes the reliance principle to protect the retracting party by allowing him to fine tune the consideration when necessary, but not allowing the performing party to stand on the waiver beyond the time that it is commercially reasonable to do so. a. Ex: waiver of rent during wartime can be rescinded at the end of a war without violating reliance of performing party. C. Under UCC 2-208 a waiver or modification can be implied from the course of performance a non-conforming performance is not objected to. 1. By acquiescence in performance. 2. By accord and satisfaction when he receives adequate notice. a. The party seeking waiver or modification must be acting in good faith, which means that the notice given must be reasonable under the circumstances. Roger W. Martin 8 Contracts Outline Printed: March 6, 2016 III. Objective view of risk distribution language vs. mistake A. Where a discrepancy (mistake) exists in the parties' "subjective" understanding of what the contract means, the court will use the construction of the party who has been most commercially reasonable in good faith. 1. This keeps the parties within the framework of the consideration, and regulates them by encouraging better communications and more care in contract formation. 2. Ex: Where a buyer purchases manila ropes at a gov't auction where all warranties are expressly disclaimed (thus the price can be slashed as at a garage sale), he bears the risk that the ropes are of poor quality or even a different kind if he does not act with commercial reasonableness and inspect them first. He can not claim that he reasonably relied on them being of high quality if he did not inspect them. 3. Ex: Restatement: If a person offers to sell his cow, but accidentally states "horse", and the offeree knows of the mistake and therefore promptly accepts, there is a contract for the cow, not the horse. B. Where both parties have been equally commercially reasonable, then they both deserve to have at least their reliance interests protected because each relied on a reasonable construction of the contract. IV. Discharge and Impossibility A. Under a strict test, few performances are ever really "impossible". Almost any performance can be completed by some extremely large expenditure of resources. 1. Thus, impossiblity does not excuse performance, it simply requires the alternative of paying damages or a substitute performance. 2. However, damages may be difficult to calculate. B. Parties may contract, as part of their consideration, to be discharged from any further obligation upon the happening of a certain event. 1. Ex: A contract to rent an opera house may have the implied condition that the parties will be discharged if the opera house burns down. This depends on an objective view of the consideration taking into account what other options are commercially reasonable. C. Discharge necessarily affects the risk distribution between the parties, especially where there has been a partial performance by one of the parties. 1. It is not enough to put the parties back in the position that they were before contracting, because the risks have grown and shifted with time. Thus, there is an increment of risk created. 2. When parties are discharged, the court must balance the respective restitution and reliance interests between them, in which case the restitution interest is protected first. Often this can be done by letting the losses remain where they fell. Roger W. Martin 9 Contracts Outline Printed: March 6, 2016 D. A court can choose to discharge or enforce any part or whole of a contract in order to accomplish their regulatory ends, and even impute that meaning to the parties' own consideration. Thus, a discharge would be effective regulation if it resulted in a bottom line award of damages that set an important precedent. 1. Discharge sets aside the parties' consideration, and gets directly at the protectable reliance and restitutionary interests. a. The court can be true to the consideration doctrine, even by giving priority to the resitution and reliance interests, by implying such priority into the parties' own consideration. 2. If a party expects discharge when he has run into impossibility (as an excuse), he will be surprised when the reliance principle is invoked to require him to renegotiate a modification in good faith which overcomes the impossibility and allows the consideration to evolve. a. Ex: A car salesman's failure to accept a favorable reduction in rent to avoid frustration may entitle his landlord to full protection of his expectation interest even when the frustration occurs. b. This is because the success of the law of contract is best measured when the parties' own consideration is truly reflected by being required to work it out themselves in the face of the existing risks. c. The contract becomes a container to hold the evolving consideration and put bounds on the parties' transaction. d. Ex: Even ordinary risks of market fluctuation become extraordinary when they shift so drastically that an objective view of the parties' consideration did not allow for such an event to be binding. V. Breach and Forfeiture A. "Conditions" are terms in the contract, which if broken, break the consideration. "Covenants" are all other terms. 1. The breach of a covenant does not excuse the aggrieved party from performing. He has a duty to make a good faith effort to renegotiate the contract to allow the consideration to evolve. 2. Determination of whether a term is a condition or a covenant requires an objective view of the risk distribution, but courts are more inclined to viewing questionable terms as covenants in order to keep the parties in the contract to regulate them. 3. Breach of a covenant can still result in some measure of damages for losses akin to reliance and restitution, but does not preclude expectation interest recovery. B. "Forfeiture" is a "temporal assymetry in performance", where one side has already performed and the other party breaches. 1. Almost all commercial transactions have this time lag; the longer the time lag, the more susceptible the contract is to forfeiture, in which case, Roger W. Martin 10 Contracts Outline Printed: March 6, 2016 the party with the most power generally tries not to be the first to perform. 2. Divisible contracts are less susceptible to forfeiture because each performance is matched in a relatively timely manner with a payment. 3. Construction contracts are more susceptible to forfeiture because the more the builder performs, the stronger the power of the owner to withhold payment. However, some skimping in the bid is expected as part of the normal commercial behavior of builders, so the non-conforming performance is usually part of the parties' consideration. a. Ex: Not putting brand name lead pipe into a house or spacing the joists at a wider interval are both violations of covenants that would allow recovery only for actual damages because they are not breaches which go to the heart of the contract, allowing forfeiture. b. This protects the reliance of the builder from the bad faith of the owner who claims excess damages for breach. 4. The court must weigh balance the protection of the breacher's restitutionary and reliance interests against the mandatory indifference of the consideration doctrine. We do not wish to weaken the bite of the reliance principle. 5. When the buyer has made a downpayment, and then forfeits, the seller may keep the downpayment to the extent that it represents reasonable liquidated damages, in which case it simply is a part of the parties' own consideration, reflecting the reasonable commercial practice associated with the risks of breach. VI. Remedies A. Specific Performance 1. Only awarded when monetary damages would be insufficient to protect the parties' respective interests, or to make a clear precedent based on particular facts since most cases are not litigated. (Like City Stores). 2. Risk that the performing party will do a bad job out of spite if compelled to affirmative performance. 3. Negative injuctions are only slightly better, because they motivate renegotiation, allowing the consideration to evolve. However, they alter the bargaining power of the parties so substantially that a resulting settlement might not reflect the parties' original consideration. 4. A contract clause that provides for specific performance as the remedy may be ignored by the court as being too lopsided, especially if money damages would be sufficient. Thus, even where explicit, a specific performance remedy could be viewed as outside of the consideration, pushing an otherwise enforceable contract provision "over the edge". 5. An arbitration award of specific performance would carry more weight than a naked specific performance clause because it would incorporate the Roger W. Martin 11 Contracts Outline Printed: March 6, 2016 risk of the abitrator's judgment into the consideration, in much the same was as price indexing. B. Liquidated damages 1. Express liquidated damages are generally the best representation of the parties' own consideration, unless they are so out of whack with an objective view of the contract as to amount to a penalty. 2. The implied liquidated damages in most cases it the lesser of the cost of completion and the difference between the value promised and the received performance. a. Ex: Even an express term to require a strip miner to level the land after mining is construed as a promise to pay for the decrease in value to the land because such a high cost of breach was not objectively part of the consideration. The farmer could not reasonably rely on the express term being taken at face value. b. The court can not be an effective regulator of commercial transactions if it is required to take into account the subjective value of performance to any individual. C. Sale of Goods (Contract - Market differential and cover) 1.If a buyer does not attempt cover, then he is not entitled to lost profits because the transaction has not been completed, thus there is a possibility that the award would be used for other purposes and represent a windfall to the buyer. Better to let the buyer behave in the actual market as he would have if the seller had performed, and then make up the difference. a. buyer who does not cover recovers the loss he would have suffered if he had covered. b. buyer who does cover recovers his actual losses, which include incidental damages and lost profit. 2. §2-708 - (2) If the contract-market differential is inadequate to put the seller in as good a position as performance would have done, then he may recover the profit he would have made on the sale, as well as reasonable reliance damages. [Lost volume seller may recover profit because of lost opportunity.] 3. §2-713 - The buyer's remedy for seller's breach is the contract-market differential at the time the buyer learned of the breach, [protecting the reliance of the buyer on the contract until he has notice] at the place of delivery. 4. §2-715 - The buyer's incidental damages include cost of rejection, and covering the breach. (2) Additionally, the buyer may recover for any loss resulting from the the needs of the buyer which the seller had reason to know of at the time of contracting, and which could not be reasonably covered [losses which were part of the consideration]; and personal injury caused by breach of warranty. Roger W. Martin 12 Contracts Outline Printed: March 6, 2016 a. losses which are not part of the consideration (objectively viewed) are not recoverable - Ex: telegram company is not liable for anything more than the price of transmission because the consideration does not allow it. b. Just because the breaching party had notice of the potential loss, does not mean that he assumed the risk of it. VII. Repudiation A. Upon repudiation, any increment of risk is assigned to the repudiating party that the risks that have accumulated and changed since contract formation will be assigned to him. This is accomplished by moving up the date for performance. 1. The seller who repudiates suddenly has the risk that the market price is higher now than it would be on the date of performance. This requires him to pay damages now so that the buyer can effect cover. 2. This is not applicable to repudiations that do not increases the corpus of risk, like simple debts (loans) where one side has already fully performed (unilateral transactions). B. UCC Section 2-610 - Anticipatory repudiation. 1. The repudiation must be with respect to a performance not yet due, which substantially impairs the value of the contract [burden of risk increased such as by bad faith or demand for performance outside of the consideration] to the aggrieved party. The aggrieved party has the option of (a) waiting for a commercially reasonable time, [but if he waits longer, he can not recover losses he should have avoided because the consideration doctrine requires that the aggrieved party not be able to profit from the breach at the other's expense.] (b) resort to any remedy for breach even if he still urges performance, [and continue to negotiate with the repudiator in good faith.] (c) in any case suspend his own performance 2. A commercially reasonable time is fact driven, and in many cases where services or advertising are involved, the aggrieved party may even be allowed to finish performance against the repudiating party's wishes because otherwise he could not be put in as good a position as he would have had the repudiating party performed. 3. Professionals with clients are presumptively viewed as being like "lost volume" sellers, thus being entitled to lost profits for repuditation. C. UCC Section 2-611 - Retraction of Anticipatory Repudiation 1. Until his next performance is due, the repudiating party can retract his repudiation unless that would violate the reliance principle [aggrieved party relied on the repudiation as in 2-610(b).] D. UCC 2-612 - "Installment Contract" Breach Roger W. Martin 13 Contracts Outline Printed: March 6, 2016 1. If the non-conformity in one delivery impairs the value of the whole contract [increases the buyers risk based on time, quality, etc,] then there is a breach of the whole. But the buyer must notify the seller seasonably. [This sub. furthers the continuance of the contract in the absence of an overt cancellation. The whole contract is not breached if the defects are only local to the installments. This protects the seller's reliance on the buyer not being able to take advantage of minor defects to treat the contract as repudiated.] E. The common theme of the UCC codes on repudiation is to keep the parties at the bargaining table where they can continue to be regulated within their own evolving consideration, instead of requiring the consideration to break. VII. Third Party Beneficiaries. A. If they are included in the consideration they have a cause of action. Roger W. Martin 14