Motor Vehicle Admin. v. Atterbeary, Court of Appeals defense brief

advertisement

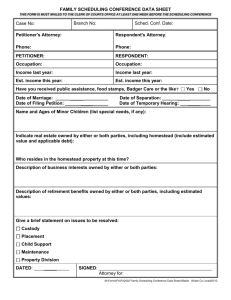

TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Authorities............................................................................. ii Statement of the Case ........................................................................ 1 Questions Presented ........................................................................... 3 Statement of Facts ............................................................................... 3 Argument A. The Circuit Court Correctly Applied Prior Decisions of this Court Upholding a Right to Contact an Attorney Before Electing to Take or Refuse a Breath Test and Correctly Found the Arresting Officer Should Have Permitted Respondent to Use the Telephone. .................................................................................................... 8 B. An Arrested Person’s Expressed Desire to Contact An Attorney Does Not Constitute a “Refusal” to Submit to Breath Testing in Violation of Maryland Law When Police Do Nothing to Permit Contact With An Attorney ...................................................................................................... 16 C. This Court Should Set Minimum Guidelines on What Police Must Do When an Arrested Drunk Driving Suspect Asserts the Desire to Contact an Attorney. ....................................................................................................... 20 D. A Motorist Who is Lawfully Parked and Making No Active Attempt to Operate a Vehicle Should Not Be Forced to Open His Window or Forced to Get Out of the Vehicle Merely Because a Police Officer Suspects the Motorist May Have Been Drinking ...................................................................................................... 25 Conclusion ............................................................................................. 32 Appendix ............................................................................................ Apx 1 i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CASES State: Albrecht v. Director of Revenue (1992, Mo App) 833 SW2d 40...........................22 Atkinson v. State [331 Md. 199 (1993).......................................................2, 26, 28 Billups v. State, 135 Md. App. 345, 354 (2000)....................................................17 Borbon v. Motor Vehicle Administration, 345 Md. 267 (1997)..............................20 Brown v. Director of Revenue, 34 S.W. 3d 166, 2000 Mo. App. LEXIS 1681......23 Cagle v. City of Gadsden, 495 So. 2d 1144, 1145 (Ala. 1986) Capretta v. Motor Vehicles Division, 29Or.App.241, 562 P2d. 1236, 1238 (1977)...................................................................................................................13 Clough v. Commissioner of Public Safety (1985, Minn App) 360 NW2d 428.......23 Dain v. Spradling (1976, Mo. App) 534 SW2d 813...............................................22 Duff v. Commissioner of Public Safety, 560 N.W.2d 735 (Minn. Ct. App. 1997)..22 Edwards v. Arizona, 451 U.S. 477, 484-85, 101 S. Ct. 1880, 68 L. Ed. 2d 378 (1981)...................................................................................................................17 Forman v. MVA, 332 Md. 201, 217 (1993)...........................................................18 Gooch v. Spradling (1975, Mo. App) 523 SW2d 861...........................................22 Hare v. MVA, 326, Md. 296, 303 (1992)...............................................................18 Kuntz v. State Highway Comr. (1987, ND) 405 NW2d 285..................................23 Little v. State, 300 Md. 485 (1984).......................................................................31 McAvoy v. State, 314 Md. 509 (1989)..................................................................16 McCann v. Commissioner of Public Safety (1985), Minn App) 361 NW2d 169.....21 MVA v. Richards, 356 Md. 356 (1999).................................................................32 MVA v. Vermeersch, 331 Md. 188, 193 (1993)....................................................17 NCR Corp. v. Comptroller, 313 Md. 118, 125, 544 A.2d 764, 767 (1988)............27 Ott v. State, 325 Md. 206 (1992)..........................................................................29 People v. Gursey, 22 N.Y.2d. 224, 292 N.Y.S.2d 416, 418, 239 N.E.2d. 351, 352 (1968)..............................................................................................................11-14 Reynolds v. State, 130 Md.App. 304 (1999).........................................................29 Peterson v. Department of Public Safety, 373 N.W.2d 38, 40 (S.D.1985)...........27 ii Sites v. State, 300 Md. 702 (1984).......................................................................10 State v. Love, 182 Ariz. 324, 326-27, 897 P.2d 626, 628-29 (Ariz. 1995)............ State v. Lawrence, 849 S.W.2d. 761, 765 (Tenn. 1993)......................................27 State v. Newton [291 Or. 788, 636 P.2d 393 (1981)............................................11 State v. Ott, 85 Md. App.632................................................................................29 Federal: Bell v. Burson, 402 U.S. 535, 91 S.Ct. 1586, 29 L.Ed.2d. 90 (1971)....................12 Davis v. United States, 512 U.S. 452, 458, 114 S. Ct. 2350................................17 Dixon v. Love, 431 U.S. 105, 97 S.Ct. 1723, 52 L.Ed.2d 172 (1977)...................12 South Dakota v. Neville, 459 U.S. 553 (1983)......................................................10 STATUTES Transportation Article, §16-205.1 Passim State Government Article, § 10-222 RULES OF COURT Maryland Rule ....................................................................................... 30 SECONDARY AUTHORITY Denial of Accused’s Request for Initial Contact with Attorney-Drunk Driving Cases, 18 A.L.R. 4th 705 (1982) iii IN THE COURT OF APPEALS OF MARYLAND ____________ SEPTEMBER TERM, 2001 ______________ No. 76 _____________ MOTOR VEHICLE ADMINISTRATION, Petitioner/Cross-Respondent, vs. KNOWLTON R. ATTERBEARY, Respondent/Cross-Petitioner _____________ On Writ of Certiorari to the Circuit Court for Howard County (Lenore R. Gelfman, Judge) BRIEF OF RESPONDENT ____________ STATEMENT OF THE CASE Respondent agrees this case concerns an administrative suspension of 120 days under Transportation Article, § 16-205.1 based upon his alleged refusal to submit to breath testing following an arrest on April 22, 2000. Respondent disagrees with Petitioner’s characterization in its Statement of the Case that an Administrative Law Judge found Respondent “was not denied an opportunity to speak with counsel before being asked to make a decision to take or refuse a sobriety test.” Brief of Petitioner, p. 2. The Administrative Law Judge actually found that Respondent “did not have an attorney to call” and that his repeated requests to talk with an attorney constituted a refusal under § 16-205.1. On appeal to the Circuit Court for Howard County (Gelfman, J.), the Circuit Court found there was ample evidence to find that Respondent had been in actual physical control of his vehicle, citing Atkinson v. State [331 Md. 199 (1993)]. However, the Circuit Court never held, as claimed by Petitioner, that “... the Officer was required to calculate the time left before he would have to call a technician to prepare and complete a chemical test, and allow Atterbeary to wait until that time and call whomever he chose.” Brief of Petitioner, pp. 2-3. What the Circuit Court did rule is that the arresting officer had decided too quickly that Respondent’s repeated requests for an attorney amounted to a refusal 3 when only 50 minutes had elapsed from the time of the arrest and only 13 minutes had elapsed since Respondent had been advised of the sanctions for taking or refusing a breath test. The Circuit Court made a fact-specific determination that it was unreasonable to call Respondent’s conduct in requesting an attorney a refusal when the police officer had not afforded him any use of the telephone. The Circuit Court also found there was “no evidence” Respondent had attempted “... to thwart the giving of the intoximeter test ... by pushing the two hour limit.” The Circuit Court felt the police officer should have permitted Respondent use of the telephone and could have properly warned him there was a deadline for Respondent to decide imposed by the need to secure an operator and meet the two-hour deadline imposed by statute. Respondent has filed a cross-petition in this Court because the police officer’s arbitrary determination that asking to contact an attorney amounted to a refusal under § 16-205.1 was not the only example of improper conduct by the officer. Earlier, when Respondent was lawfully parked with his engine running, the same officer forced Respondent to lower the window on his vehicle so that the officer could reach in, open the door and require Respondent to alight. This action was taken on mere suspicion Respondent may have consumed too much alcohol. QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Did the Circuit Court correctly interpret Maryland law allowing a motorist arrested for a driving while intoxicated a due process right to seek the advice 4 of an attorney before deciding whether to submit to blood alcohol testing? 2. Was there a “refusal” under Transportation Article, § 16-205.1, when an arrested motorist repeatedly requested an attorney to a police officer who never permitted him any use of the telephone or any other means of contacting his lawyer? 3. Should this Court establish additional guidelines on the rights of persons arrested for alcohol offenses in order to effectuate their due process right to seek advice of counsel? 4. Where a motorist is lawfully parked with the engine running, or starts the engine after request of rescue or law enforcement personnel, what quality of evidence is required before a police officer can force the motorist to open his window and remove him from the vehicle to investigate his suspicion the motorist may be intoxicated? STATEMENT OF THE FACTS A. Introduction; Additional Facts On the Right to Counsel and “Refusal”Issues When Respondent first testified before the Administrative Law Judge on July 26, 2000, he was 53 years of age and the president of a management consulting firm that had been in business for 19 years and employed between 225 and 250 employees. His business devoted much of its time to contract work in public policy issues such as housing, transportation, and mental health. [E. 29]. Respondent held both a bachelor’s and master’s degree, which he had obtained in 1975. According to two separate documents prepared by the arresting officer, Respondent was accused of, or arrested for, conduct occurring on April 22, 2000, at 1:35 a.m. See, Officer’s Certification and Order of Suspension [E. 97], which lists the “Occurrence of Offense” at that time, and the police report introduced by Respondent [E. 99], which gives the time of arrest at that time. Both the officer and Respondent agreed that all or some of the standard Advice or Rights, Form DR15, [E. 98] was read to Respondent, a process which apparently concluded at 2:12 a.m., according to 5 the Advice form itself. What next occurred, according to the officer, is that Respondent “... stated he would take the test...” [E.67]. Officer Mondini then asked Respondent to sign the Advice form, and Respondent asked to read the form first. Ibid. According to Respondent, Officer Mondini had read portions of the form and asked Respondent if he understood. According to Respondent: I said I did not understand, I ‘d like to read the form myself. He then said that I [Mondini] just read the form to you, you should understand it. I said, I’d like to read the form myself. He then projected the form in my direction across the work station or desk and then left the room. [E. 24] According to Respondent, the chronology continued when Officer Mondini returned with another officer, whom he spoke to out of Respondent’s earshot. [E.40] Officer Mondini then began filling out other forms and asked Respondent a series of questions such as his birthday, work phone number and “other administrative kinds of questions.” [E. 41] It was during these questions that Respondent said he wished to speak to an attorney, and each time he repeated that request, Officer Mondini said “... that’s a refusal.” Ibid. Respondent characterized Officer Mondini as saying this in a “gleeful” manner and clapping his hands whenever Respondent requested an attorney. Returning to forms, Respondent agreed he refused to sign the DR-15 Advice of Rights form, saying he did so because the form indicated he had refused to take a breath test, which was not true. [E. 42-43] Meanwhile, both the Advice form and the officer’s police report indicate the test was refused at 2:25 a.m., or thirteen minutes after the advice had been given. It is uncontested that the “refusal” arises from the police officer’s personal determination or conclusion that Respondent’s repeated requests for an attorney constituted a refusal under § 16-205.1. [E. 67, 84, 102]. In his police report, the officer summarized his position as follows: “By refusing to sign the form and 6 refusing to answer the writer’s questions the writer determined Atterbeary refused to submit to a test of breath.” [E. 102, emphasis supplied]. As set forth in Petitioner’s Brief, Officer Mondini wrote in his report, and in some additional notes, and testified at the hearing that Respondent told him “I don’t have an attorney at the moment.” After hearing this claim, Respondent observed that as a small businessman with 250 employees he had “... too many attorneys.” He also knew the names of attorneys he could have contacted, but did not know all of their phone numbers when arrested at around 1:35 a.m. [E. 88-89]. Respondent also contended that Officer Mondini’s only question to him had been the telephone number of the attorney Respondent wished to call. [E. 89]. He also said: The officer asked me specifically. He said, what is your attorney’s phone number. I said, I don’t know what the telephone number is. He said, somewhat gruffly, that’s a refusal. I didn’t quite understand it at the time, but I think I understand what it means now. [E. 88] Petitioner’s brief contends that Petitioner’s requests for an attorney went on 15 to 20 minutes, based on cross examination of Officer Mondini at [E. 84] Other time estimates in the record would dispute this estimate, including Officer Mondini’s report, which in relevant part reads: Once inside the processing area, the writer read the DR-15 to Atterbeary, who agreed to take the breath test. The writer asked Atterbeary to sign the DR-15, at which time he stated he wanted to read the form before signing it. Approximately 10 minutes later, Atterbeary stated he wanted to speak to his lawyer before signing the form. [E. 101] B. The Decision of the Administrative Law Judge on the Right to Counsel and Refusal Issue The transcript of the second hearing contains no reference to the ALJ’s decision, so the only item of record is the “Findings of Fact” form found in the Record Extract at E. 96. An enlarged 7 version of the relevant portion of that form is included in the Appendix to this brief at Apx - . ALJ Rothenberg seems to have written the following: Licensee asked for an attorney. When asked for name & phone number he said he did not have one at the moment. I conclude Licensee did not have an attorney to call. Thereafter, Licensee kept answering he wanted to talk with an attorney to all questions. I conclude therefore he refused to take the test. 16-205.1 C. Additional Facts Necessary to the Cross Petition The DR-15A Officer’s Certification and Order of Suspension form submitted by Officer Mondini [E. 97] contained relatively little detail concerning the location of the incident, cited only as “Montgomery County.” Respondent produced evidence at the original hearing that the location was “3121 Automotive Blvd” [E. 99], and the officer’s report also so states [E. 100]. Officer Mondini never saw Respondent driving the vehicle anywhere [E. 76], and was called to the scene, where a black man in a Mercedes was parked with the engine on when Mondini arrived. [E. 100] The record does not disclose whether the engine was running when fire-rescue personnel first accosted Respondent prior to Mondini’s arrival. However, only the fact the engine was running mattered to the Officer. As Officer Mondini stated at the second hearing, The engine was on. I believe in accordance with the State of Maryland when the engine is on and the person is behind the wheel, that’s considered driving. The DR-15A indicates Officer Mondini “received a call for subject slumped over the wheel” [E. 97], but his report characterizes the dispatch “for a report of one down via fire rescue.” [E. 100] There was no indication in the police report or the testimony at the second hearing that fire rescue personnel told Officer Mondini that Respondent had been slumped over the wheel, and no evidence of the dispatch itself was ever adduced. At the hearing, Officer Mondini said: 8 We spoke to the paramedics. They said that there’s a gentlemen in the Mercedes who refused to open the door, roll down the window. They just wanted to make sure he was okay and they detected a strong odor of alcohol. They told us that he didn’t want to come out of the car and (INAUDIBLE) okay, we’ll go talk to him. I go and try to speak Mr. Atterbeary and ask him if he could step of the car or at least roll down the window. He said, what for, exactly what he said. I don’t have to do that. He had rolled down the window enough that I reached in, opened the door. I reached in and unlocked the door, opened the door, asked him to step out. At which time again I remember him saying, he goes, why do I have to do that? He was uncooperative and I detected a strong odor of alcohol emitting from him. His speech was slurred, he was stuttering. His eyes were bloodshot and watery. At which time, I asked him that he needed to step out of the vehicle and I told him that he needed to turn his engine off. I asked him to step out so I could conduct some standard field sobriety tests. He did step out. [E. 64-65] The police report is largely similar in its description of the facts [E. 100], but neither testimony nor the report mention that “Atterbeary argued with the Officer” when asked to turn off the engine. Brief of Petitioner, p. 6. Respondent did assert his belief that he did not have to roll down his window or exit the vehicle, and had to be “convinced” to lower the power window on his car. As soon as he did so, Officer Mondini reached into the vehicle and opened the door without Respondent’s permission. [E. 77-78] Officer Mondini then required Respondent to get out of the vehicle. [E. 78] It was during this process that Officer Mondini believed Respondent was not a cooperative person. Ibid. No testimony was offered about whether the vehicle’s headlights were on, the hood warm, nor was any explanation offered for the vehicle being parked near several auto dealerships. Counsel for Respondent argued at the first hearing that 9 the roadway involved was not a “highway or private property used by the public in general,” [E. 23-26], but this was disputed by Officer Mondini when he testified at the second hearing [E. 71-73]. There was no dispute that Respondent’s vehicle was parked in a parking space beside the curb in a normal manner. ARGUMENT A. The Circuit Court Correctly Applied Prior Decisions of this Court Upholding a Right to Contact an Attorney Before Electing to Take or Refuse a Breath Test and Correctly Found the Arresting Officer Should Have Permitted Respondent to Use the Telephone. In its Petition for Writ of Certiorari, and again in its brief, the Motor Vehicle Administration has misrepresented the decision of the Circuit Court. In its Petition, MVA contended that “... the circuit court found the Officer was required to calculate how long it would take to obtain a test technician, prepare and conduct a Breathalyzer test within two hours, and allow Respondent to sit with a telephone up to that time before making a decision to take the test.” Petition, page 2. This position has been altered slightly in this Court, where MVA’s Brief claims the Circuit Court “... erroneously believed a ‘reasonable opportunity’ to communicate with counsel must necessarily include all of the time available before a police-calculated deadline to commence preparation and administer a chemical test within two hours 10 of apprehension, as required by § 10-303(a) of the Courts Article.” MVA’s position is not borne out by a fair reading of Judge Gelfman’s oral remarks following argument [E. 2–15]. The Judge clearly set forth all of the respective arguments made by each side, including MVA’s contentions about the counsel issue. Then, in deciding that Officer Mondini had “... jumped the gun...” [E. 13], she illustrated precisely the evil that MVA seeks to prevent, saying: I think the evidence ---- there is no evidence in the transcript that says, look, we need to get a breathalyzer operator in here. We need to have x-amount of minutes in order to start up the machine and so forth. There is no question that an individual can thwart or attempt to thwart the giving of the intoximeter test or other breath test or test by blood, by pushing the two-hour limit. But there is no evidence of that here. In other words, there is no testimony that I found in the record that where Officer Mondini said, look, we went back to the Silver Springs [sic] station; but I would have, at that hour of the morning, I would have had to call in an intoximeter person, and I told the defendant that that’s going to take 22 minutes, approximately, and it’s going to take x minutes to start up the machine, et cetera, et cetera. There is nothing in there. So when you take a look at the time of the arrest, and the time the officer determined a refusal, it was just too quick. And, therefore, the Court, while it agrees that the State has no obligation to provide information specific to an arrestee of a name, or address or phone number of an attorney, basically, in my opinion, Officer Mondini should have said, you know, Mr. Atterbeary, here’s the phone, call whoever you want. And if Mr. Atterbeary could not get in touch with an attorney, the officer should have said, Mr. Atterbeary, I need to have your election by X and X time. I have to take the test within two hours. And If you don’t tell me by such a such time, that’s going to thwart that, and I have then count that as a refusal. Basically, Officer Mondini just went too far – too fast, I should say. 11 [E. 13-14, Emphasis supplied] It is obvious, by reading Judge Gelfman’s remarks in proper context, that she was saying the police officer would have been within his rights to give Respondent much less than the full two hours. What she was suggesting is that the police officer should have given Respondent the simple opportunity to use the phone, but warn him that he was not going to be allowed to thwart the test by delaying a decision past the point when a technician could be secured and the equipment properly set up. This suggestion is completely consistent with the prior holdings of this Court, and the importance of the decision facing an arrested driver concerning his options to take or refuse a test. Eighteen years ago, the Supreme Court decided South Dakota v. Neville, 459 U.S. 553 (1983), a case dealing with the right of a State to revoke a driver’s license for refusal to submit to breath testing, and the permissibility of allowing evidence of refusal to be adduced before the trier of fact. The Court noted: “We recognize, of course, that the choice to submit or refuse to take a blood-alcohol test will not be an easy or pleasant one for a suspect to make.” [Emphasis supplied] Neville did not deal with the right of a suspect in this situation to consult with an attorney, but that right is firmly rooted in Maryland law since this Court decided Sites v. State, 300 Md. 702 (1984) less than eighteen months later. The defendant in that case had been arrested at 12:45 a.m., and advised of his obligations 12 regarding breath testing at the scene of his arrest. He initially agreed, but then sought to contact an attorney after he arrived at the police station. According to Sites, he sought counsel three times, both before and after a breathalyser test was actually administered at 1:25 a.m. The arresting officer told him he had no right to counsel, and no phone calls were permitted. In a lengthy discussion, this Court first determined that Sites had no Sixth Amendment right to counsel, but then discussed the argument of a due process right in detail. One case argued by Sites was People v. Gursey, 22 N.Y.2d 224, 292 N.Y.S.2d 416, 239 N.E.2d 351 (1968), in which the Court of Appeals of New York concluded "that the test results were secured in violation of defendant's privilege of access to counsel without occasioning any significant or obstructive delay." Id., at 352 That court also held: [L]aw enforcement officials may not, without justification, prevent access between the criminal accused and his lawyer, available in person or by immediate telephone communication, if such access does not interfere unduly with the matter at hand.... *** *** "... Granting defendant's requests would not have substantially interfered with the investigative procedure, since the telephone call would have been concluded in a matter of minutes.... Consequently, the denial of defendant's requests for an opportunity to telephone his lawyer must be deemed to have violated his privilege of access to counsel." Id. at 352-53. [Emphasis supplied] This Court also cited with approval, the following: 13 In State v. Newton [291 Or. 788, 636 P.2d 393 (1981) ] the Supreme Court of Oregon, while finding no Sixth Amendment right to counsel, concluded in a plurality opinion that the right of a person arrested for drunk driving timely to call his lawyer before taking the test was traditionally and rigorously observed with "roots deep in the law." 636 P.2d at 405. The plurality found the right to be so fundamental as to be embodied in the Fourteenth Amendment and thus to inhibit states to "deprive any person of ... liberty [481 A.2d 199] ... without due process of law." The court said that the defendant's freedom to call a lawyer before deciding whether to submit to a breathalyzer test was safeguarded by the Fourteenth Amendment, and specifically by the "Defendant's liberty to communicate," which was deemed a significant and substantial liberty free from "purposeless restraints." 636 P.2d at 406. The plurality said that "allowance of a telephone call following an arrest has become traditional and incommunicado incarceration is regarded as inconsistent with American notions of ordered liberty." Id. at 406. (FN4) [Emphasis supplied] The Court then quoted from Neville, supra, and said: By affording a suspect the power to refuse chemical testing, Maryland's implied consent statute deliberately gives the driver a choice between two different potential sanctions, each affecting vitally important interests. Indeed, revocation of a driver's license may burden the ordinary driver as much or more than the traditional criminal sanctions of fine or imprisonment. The continued possession of a driver's license, as the Supreme Court has said, may become essential to earning a livelihood; as such, it is an entitlement which cannot be taken without the due process mandated by the Fourteenth Amendment. See Dixon v. Love, 431 U.S. 105, 97 S.Ct. 1723, 52 L.Ed.2d 172 (1977); Bell v. Burson, 402 U.S. 535, 91 S.Ct. 1586, 29 L.Ed.2d 90 (1971). Considering all the circumstances, we think to unreasonably deny a requested right of access to counsel to a drunk driving suspect offends a sense of justice which impairs the fundamental fairness of the proceeding. We hold, therefore, that the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, as well as Article 24 of the Maryland Declaration of Rights, requires that a person under 14 detention for drunk driving must, on request, be permitted a reasonable opportunity to communicate with counsel before submitting to a chemical sobriety test, as long as such attempted communication will not substantially interfere with the timely and efficacious administration of the testing process. In this regard, it is not possible to establish a bright line rule as to what constitutes a reasonable delay, although the statute itself mandates that in no event may the test be administered later than two hours after the driver's apprehension. Of course, it is the statutory purpose to obtain the best evidence of blood alcohol content as may be practicable in the circumstances, and it is common knowledge that such content dissipates rapidly with the passage of time. Thus, if counsel cannot be contacted within a reasonable time, the arrestee may be required to make a decision regarding testing without the advice of counsel. We emphasize that in no event can the right to communicate with counsel be permitted to delay the test for an unreasonable time since, to be sure, that would impair the accuracy of the test and defeat the purpose of the statute. Manifestly, whether a driver who seeks to communicate with counsel has been denied his due process right to do so depends on the circumstances of each case. Where that right is plainly violated, and the individual submits to the test, we think the only effective sanction is suppression of the test results where adverse to the defendant. A reviewing court, however, should afford great deference to the determination of the police authorities that denial of the requested right of access to counsel was reasonably necessary for the timely administration of the chemical sobriety test. [Emphasis supplied] Three years after Sites, this Court clarified and expanded the meaning of the right to consult with counsel in an action brought by an attorney, Gil Cochran, who had been denied access to potential clients by a State Police general order that limited contact to telephonic communication. Additionally, Cochran sought the right to give clients a breath test on his own equipment brought to the station for that purpose. This Court held: 15 Contrary to the Superintendent's first contention, nothing in Sites limits the due process right to communicate with counsel to a single telephonic contact. Undoubtedly, the statutory time constraints imposed upon the State-administered blood alcohol testing process may well limit the client's ability to communicate with counsel other than by a single telephone conversation. But to so circumscribe the due process right far too narrowly restricts the scope of the constitutional right recognized in Sites. (FN1) Nor is the constitutional right to counsel in any event limited solely to lawyer-client telephonic communication, as the Superintendent further contends. In no way did we limit the mode of lawyer-client communication in Sites or otherwise differentiate between telephone and face-to-face consultation. Indeed, we quoted with approval from a New York Court of Appeals case which involved, as here, the right of a drunk driver suspect to counsel prior to deciding whether to submit to the sobriety test: " '[L]aw enforcement officials may not, without justification, prevent access between the criminal accused and his lawyer, available in person or by immediate telephone communication, if such access does not interfere unduly with the matter at hand....' " Sites, supra, at 713, 481 A.2d 192 (quoting People v. Gursey, 22 N.Y.2d 224, 292 N.Y.S.2d 416, 418, 239 N.E.2d 351, 352 (1968) (emphasis added)). (FN2) We thus agree with Judge Williams that "whether the communication is by phone or in person is irrelevant; the operative question is whether the requested communication would unreasonably impede police processing." See also Capretta v. Motor Vehicles Division, 29 Or.App. 241, 562 P.2d 1236, 1238 (1977) ("[w]hether counsel is available at the station or at the other end of a telephone line is not a pertinent distinction"). Of course, in neither event may drunk driver suspects postpone the decision whether to submit to the state chemical sobriety test until they have consulted with their attorneys, whether personally or by telephone, if the attorney is not available [516 A.2d 975] on a timely basis. What constitutes timeliness is to a large extent determined by the facts of the particular case but, under no circumstances, may the time period exceed the two-hour limit imposed by statute. 16 [Emphasis supplied] None of the case decisions holds or implies that the right to consult with counsel only exists where the suspect under arrest already knows an attorney, has his telephone number, and is able to reach him or her on the first attempt. A “requested communication” to locate and then contact an attorney must only satisfy the requirement that it “not unreasonably impede police processing,” or “such attempted communication will not substantially interfere with the timely and efficacious administration of the testing process." Sites, supra, 300 Md. at 717, 481 A.2d 192. Respondent in this case was in police custody for approximately 37 minutes from the time of arrest to the completion of the DR–15 Advice of Rights form. So far as the record discloses, Respondent did not know until 2:12 a.m. that he had the ‘difficult decision’ to make, and the form itself contains a number of alternative sanctions that are indeed difficult to weigh. “DWI” laws have become increasingly complex with new statutes and procedures being enacted almost every year. Although initially willing to take a breath test, Respondent wisely and properly requested the opportunity to read the DR-15 form before signing it, then requested an opportunity to call an attorney repeatedly when asked questions by the officer. Sites places the burden on the motorist to make the request in the first instance. The question becomes, then, what must the police officer do when the request is 17 made? Sites, of course, recognizes that each case will be different, and this case involved a request by the motorist not more that 10 minutes after the advice was given and a determination by the officer that the motorist was refusing the test only three minutes later. This conclusion was reached because of Respondent’s alleged reply that he ‘did not have an attorney at the moment’ when Officer Mondini asked for the name and phone number of Respondent’s lawyer. Respondent believes that nothing in Sites requires a motorist to answer such a question as a pre-condition for using a telephone to contact a lawyer. On the contrary, an arrested individual might want to keep confidential the identity of his lawyer, or might have to call several possible attorneys before reaching anyone at around 2:30 a.m. Officer Mondini’s request for information seems to be a “purposeless restraint” [State v. Newton, supra, cited in Sites] on the exercise of the right to contact counsel. And the Circuit Court was completely correct in finding Officer Mondini acted “too quickly” in declaring a refusal at some point between 3 and 13 minutes after Respondent was advised. MVA’s brief contends that Judge Gelfman imposed a requirement that certain advice be given to motorists such as Respondent. MVA misreads the judge, who was only trying to illustrate potential things officer Mondini could have done before determining a refusal existed. The most important of these was simply to have let Respondent use the telephone, whether or not he could give the name and telephone number of a lawyer. At no point did she hold that Respondent or others similarly situated had to be advised of a 18 specific deadline at or near the ‘two hour limit’ or given the “panopoly of advice” MVA claims Judge Gelfman ordered. MVA’s reliance on McAvoy v. State, 314 Md. 509 (1989) is also misplaced. That case does hold that a motorist need not be advised of the right to counsel, but it also reiterated “[T]he right McAvoy did enjoy at that point was the right not to be unreasonably refused counsel when requested by him.” 314 Md., at 519. In the end, Judge Gelfman found, and this Court should hold, that the issue was not whether Respondent knew an attorney’s name and phone number, but whether the officer had the right to declare a refusal without giving Respondent the simple use of the telephone to call one. B. An Arrested Person’s Expressed Desire to Contact An Attorney Does Not Constitute a “Refusal” to Submit to Breath Testing in Violation of Maryland Law When Police Do Nothing to Permit Contact With An Attorney Maryland statutes do not define the word “refusal.” The verb “refuse,” however, is defined in the American Heritage Dictionary as: “To indicate unwillingness to do, accept, give, or allow. b. To indicate unwillingness (to do something)” In the instant case, Respondent initially agreed to take a test, but asked the opportunity to read the form advising him of his rights. He requested counsel shortly after he read the form. Respondent was never permitted access to a telephone directory or to the telephone. Officer Mondini’s testimony does not indicate that Petitioner ever affirmatively refused the test, but rather indicates that 19 Petitioner kept asserting his right to counsel, and the officer interpreted Petitioner’s request as a “refusal.” The officer’s position was clearly stated in the police report: “By refusing to sign the form and refusing to answer the writer’s questions, the writer determined Atterbeary refused to submit to a test of breath.” [E. 100] [Emphasis supplied.] Thus, the officer never elicited from Petitioner an actual refusal. Rather, the officer never responded to Petitioner’s requests for counsel, and interpreted these repeated requests as a refusal to take a breath test. The testimony and record do not support the factual finding of ALJ Rothenburg that Petitioner refused to submit to the breath test. “A test for alcohol concentration is refused when the driver, after having been advised pursuant to section 16-205.1(b), declines the officer’s request to submit to the test.” MVA v. Vermeersch, 331 Md. 188, 193 (1993) [emphasis added] Petitioner’s request for an attorney and his refusal to sign a form are not tantamount to “declining” to submit to a test. Thus, the officer unilaterally and unreasonably determined that a request for legal counsel was a “refusal.” Additionally, Officer Mondini acted improperly in continuing to question Petitioner after he made his initial request for an attorney. As the Court of Special Appeals recently stated in Billups v. State, 135 Md. App. 345, 354 (2000), “Once such an assertion is made by a suspect, law enforcement officials must cease all questioning until an attorney has been made available or the suspect himself 20 reinitiates conversation. See Davis [v. United States, 512 U.S. 452,] 458, 114 S. Ct. 2350 (citing Edwards v. Arizona, 451 U.S. 477, 484-85, 101 S. Ct. 1880, 68 L. Ed. 2d 378 (1981)).” The right to counsel is meaningless if a police officer may ignore a arrested person’s requests for an attorney. It is true, of course, that this Court has held, where counsel has not been contacted within a reasonable time, the police officer may require a motorist to make a final decision regarding whether or not to take a breathalyzer test. Sites, supra, at 718. Thus, following a reasonable opportunity to contact counsel, it may have been permissible for the officer to question Petitioner regarding whether he would consent to the test. Those are not the facts of this case, however. Here, Petitioner was never given any opportunity to contact counsel, but the officer continued to question him and determined that each assertion of the right to counsel should be deemed a “refusal.” A prerequisite to the MVA’s suspension of a driver’s license after a hearing is a finding that the police officer “requested a test after the person was fully advised of the administrative sanctions that shall be imposed... Fully advised means not only initially, but the detaining officer must also take care not to subsequently confuse or mislead the driver as to his or her rights under the statute” Forman v. MVA, 332 Md. 201, 217 (1993). In this case the officer failed to clarify Petitioner’s intentions regarding the breath test, after Petitioner had asserted his right to counsel, resulting 21 in a form of legal confusion about his rights analogous to the rights enunciated in Forman. The legislative intent of §16-205.1 is to encourage drivers to take a breath test if they are suspected of driving while intoxicated. Hare v. MVA, 326 Md. 296, 303 (1992). In furtherance of that legislative objective, “the officer must not in any way induce the driver into refusing the test, a result running counter to the statute’s purpose of encouraging drivers to submit to alcohol concentration tests.” Forman, 332 Md. at 217. Legislative policy also favors the taking of a test, even where there is an initial refusal. Transportation Article, §16-205.1(g) provides, in pertinent part, (g) Withdrawal of initial refusal to take test; subsequent consent. – (1) An initial refusal to take a test that is withdrawn as provided in this subsection is not a refusal to take a test for the purposes of this section. (2) A person who initially refuses to take a test may withdraw the initial refusal and subsequently consent to take the test if the subsequent consent: (i) Is unequivocal; (ii) Does not substantially interfere with the timely and efficacious administration of the test; and (iii) Is given by the person: 1. Before the delay in testing would materially affect the outcome of the test; and 2. A. For the purpose of a test for determining alcohol concentration, within 2 hours of the person’s apprehension; or B. For the purpose of a test for determining the drug or controlled dangerous substance content of the person’s blood, within 3 hours of the person’s apprehension. Thus, even if Petitioner had initially refused to take the test, he was permitted by 22 statute to withdraw that refusal, under certain circumstances, within two hours of his arrest. Given that Petitioner (1) initially agreed to take the test; (2) never affirmatively refused to take the test, and (3) requested counsel to assist him in deciding that issue, it was plain legal error for Officer Mondini to declare a refusal had occurred. The Administrative Law Judge merely adopted the Officer’s erroneous conclusion. Judge Gelfman was within her rights by refusing to uphold the legal error made below. The statutory authority for the circuit courts to provide review of administrative decisions of State agencies is found in State Government Article, § 10-222, generally, and includes review of any final decision in a contested case. The right to reverse, modify, or remand is found in subsection (h), which provides: (h) Decision. - In a proceeding under this section, the court may: (1) remand the case for further proceedings; (2) affirm the decision of the agency; or (3) reverse or modify the decision if any substantial right of the petitioner may have been prejudiced because a finding, conclusion, or decision of the agency: (i) is unconstitutional (ii) exceeds the statutory authority or jurisdiction of the agency; (iii) results from an unlawful procedure; (iv) is affected by an other error of law; (v) is unsupported by competent, material, and substantial evidence in light of the entire record as submitted; or (vi) is arbitrary or capricious. [Emphasis supplied] 23 In the hearing before the Administrative Law Judge, MVA failed to meet its burden of proof, and the case has some analogies to Borbon v. Motor Vehicle Administration, 345 Md. 267 (1997). That case dealt with the decision of another ALJ, who found that Borbon had “refused” the test by submitting an inadequate breath sample. In order to constitute a refusal, MVA had to show that the motorist had intentionally frustrated the taking of the test, and the ALJ had the duty to make a credibility determination. See, generally, the discussion at 345 Md,, 281-283. Here, the only credibility determination made by this ALJ was that Respondent “... did not have an attorney to call...” [E. 96] It was because of that fact that his continued requests for an attorney constituted a refusal in the ALJ’s findings. Judge Gelfman’s approach clearly supports the due process right to contact an attorney as enunciated in Sites and Brosan. Judge Rothenberg’s rubber- stamping of the officer’s hasty conclusion does not. C. This Court Should Set Minimum Guidelines on What Police Must Do When an Arrested Drunk Driving Suspect Asserts the Desire to Contact an Attorney. The arresting officer’s apparent belief that Respondent had to identify the name and telephone number of a lawyer before being permitted to contact one unnecessarily impinges the right itself. Upholding that idea would also violate common sense. Few people have a lawyer on retainer, or plan for being arrested 24 for various crimes. Additionally, advising one properly on the intricacies of taking or refusing a breath test arguably requires a specialist, and most people would have to consult a telephone book, or call a friend or relative in order to find an adequate lawyer late at night when most lawyer’s offices are certainly closed. Although the difficulty of the task facing a motorist such as Respondent may mean that an attorney cannot always be reached before the decision to take or refused is compelled by the circumstances, difficulty alone is no basis to permit what happened here. Respondent was alone in a ‘police dominated’ atmosphere and faced with a police officer who already felt he was “uncooperative.” The DR-15 Advice form, even if facially proper advice, contains a vocabulary and a set of choices with which most people are unfamiliar. Several major substantive changes to Maryland DUI laws have been made since this case occurred, with a lower test result leading to more severe potential punishment, and the fact of refusal has now become clearly admissible in evidence. Almost anyone could use the advice of an attorney in making the difficult decision involved. Issues of the sort raised in this case have been the subject of a comprehensive annotation. “Denial of Accused’s Request for Initial Contact with Attorney–Drunk Driving Cases, 18 A.L.R. 4th 705 (1982). Some of the situations in which the right of the motorist to contact an attorney are set forth below, directly as discussed in the annotation: 25 Limited right of motorist, arrested for driving while intoxicated (DWI), to attorney was not violated when officer ignored motorist's first request for an attorney, where officers were completing testing of another driver arrested for DWI, had no duty to interrupt their work, and it was reasonable for them to let motorist wait few minutes to insure that adequate security was available; arresting officer deprived motorist of his right to counsel, however, when he ignored request made immediately before implied consent interview in that, at this point, officer was obligated to vindicate motorist's right to contact attorney. McCann v Commissioner of Public Safety (1985, Minn App) 361 NW2d 169. Arresting officer deprived drunk-driving arrestee of statutory right to consult with attorney prior to making decisions as to chemical testing for blood alcohol level, where, in early morning hours, arrestee contacted attorney's answering service and attorney called police station within half hour, but officer arbitrarily ordered arrestee to terminate conversation before attorney could advise arrestee of such matters as his statutory right to independent testing, with result that trial court erred in sustaining administrative revocation of driver's license under implied consent law. Duff v. Commissioner of Public Safety, 560 N.W.2d 735 (Minn. Ct. App. 1997). In Gooch v Spradling (1975, Mo App) 523 SW2d 861, where a person arrested for driving a motor vehicle while intoxicated testified that he refused to take a breathalyzer test after his requests to consult his attorney were refused, the court held that there had been no unequivocal refusal to take a breathalyzer test warranting license revocation, and the court, in effect, ordered reinstatement of the accused's driver's license. The court noted that the accused said that he would not take any test until he talked to his lawyer, and that the police department policy was not to allow phone calls until a party was booked and not to book until after tests were made. The court stated that the accused was denied his right to representation and advice of counsel under a state court rule governing practice and procedure with reference to traffic cases which provided, inter alia, that every person arrested and held in custody by any peace officer should be permitted to consult with counsel or other persons in his behalf at all times. Although the court recognized that the protection of the rule could be so abused by an accused that a chemical analysis would become useless by the lapse of time and that such abuse would be tantamount to a refusal to submit to the test and would justify revocation, it emphasized that such was not the factual situation here. It pointed out that the record did not indicate that the accused's request to contact his lawyer could not have been accomplished within a few minutes by a telephone call or counsel's presence secured within an hour. In Dain v Spradling (1976, Mo App) 534 SW2d 813, where a person arrested for operating a motor vehicle while intoxicated refused to take a breathalyzer test after her request to call a lawyer or friend for advice was 26 denied, the court stated that the accused did not make an unequivocal and informed refusal to take the test and directed, in effect, that the driver's license of the accused not be revoked. The court stated that although the accused did not have a constitutional right to consult with an attorney prior to deciding whether to submit to a breathalyzer test, under state statutes and court rules the accused had the right to consult with counsel or others and the arresting authorities did not have the right to prevent the accused from doing so. The court added that the accused was not entitled to have counsel present when the test was administered but that she was entitled to obtain the advice of counsel or friend as to whether she should take the test or refuse to do so. The court noted that her request was denied before she was asked to take a breathalyzer test or given the opportunity to do so and that after she was permitted to use a telephone she was not afforded an opportunity to refuse the test or to take it. Failure of arresting officer to respond to drunk-driving arrestee's request to consult counsel prior to deciding whether to submit to test of blood-alcohol level vitiated purported refusal and automatic license revocation. Albrecht v Director of Revenue (1992, Mo App) 833 SW2d 40. Arrested person who asked to consult with attorney before deciding to take chemical test must be given reasonable opportunity to do so if it does not materially interfere with administration of test, and if he is not given reasonable opportunity, his failure to take test is not refusal upon which to revoke license under governing statute. Kuntz v State Highway Comr. (1987, ND) 405 NW2d 285. Defendant, who been arrested for driving while intoxicated, was denied his limited right to counsel under implied consent laws, where at suggestion of arresting officer defendant waited 20 minutes for telephone call from public defender, which was not returned, and where officer then denied defendant opportunity to contact his parents to obtain name of attorney. Clough v Commissioner of Public Safety (1985, Minn App) 360 NW2d 428. Some states, Missouri among them, have statutes that provide for specific time periods after advice is given in which the motorist is to be allowed the opportunity to contact an attorney. See Brown v. Director of Revenue, 34 S.W. 3d 166; 2000 Mo. App. LEXIS 1681 [20 minutes required after advice given]. Present counsel is unable to devote sufficient time [and Respondent’s 27 financial resources] to synthesizing all of the cases, statutes and annotations that have discussed this subject, but Sites and Brosan, supra, remain the law of this State. We are not here dealing with foreign terrorists who may use the opportunity to contact an attorney or friend or relative in order to inflict harm on others, or escape from custody. We are dealing with ordinary citizens – some of whom are, like Respondent, pillars of the community – who need and seek relevant advice concerning an important issue. MVA’s position in the current appeal seems to demonstrate an intention to erode this Court’s prior decisions and render meaningless the right to contact counsel. MVA wants this Court to uphold the angry judgment of a police officer who was already provoked by an “uncooperative” subject that was now requesting an attorney. Instead, this Court should delineate a few practical and reasonable methods of effectuating the rights our citizens have. May we humbly suggest: 1. Access to telephone books and telephone equipment; 2. Ability to call friends, relatives, attorneys or their answering services; 3. Ability to leave a call-back number so that the persons listed in 2 can provide information to the arrestee about reaching the attorney; 4. A reasonable and perhaps minimum time to accomplish contact that takes into consideration the time of day or night when the advice is being sought, but in no way 28 prevents administration of the breath test in a timely manner.1 Alcohol enforcement has become more vigorous, the laws have become more complex, and the penalties more severe. This is not the time lessen the ‘process that is due’ where the right to counsel is actively and properly asserted. D. A Motorist Who is Lawfully Parked and Making No Active Attempt to Operate a Vehicle Should Not Be Forced to Open His Window or Forced to Get Out of the Vehicle Merely Because a Police Officer Suspects the Motorist May Have Been Drinking In considering the issue presented in the cross petition It is important to recognize that this case was not the product of a routine arrest where a police officer had followed a motorist, noticed weaving or some traffic violation, stopped him and detected symptoms of intoxication. At the time the police officer first had contact with Respondent, it is unrebutted that he was not then driving any vehicle. Respondent also made no attempt to drive the vehicle in the presence of a police officer. In fact, according to all the testimony and documentary evidence, the officer was dispatched to the scene, where he found fire-resue personnel already present, 1Counsel will note in passing that current technology, including the Intoximeter EC/IR, does not require lengthy warmup, and that the availability of technicians in metropolitan jurisdictions like Montgomery County is seldom a real problem. Obviously a “bright line” rule is impossible, but some rule recognizing the factors on which the decision depends would help everyone. 29 Respondent in the driver’s seat of his car with the engine running, but parked lawfully alone a roadway adjacent to several automobile dealerships. The obligation to take a chemical test is part of what is generally referred to as an "Implied Consent" law. That is, by using the roads of this State, both residents and non-residents give their implied consent to submit to alcohol testing under certain conditions. Currently, these rules are found in Transportation Article, § 16-205.1(a)(2), which states: Any person who drives or attempts to drive a motor vehicle on a highway or any private property that is used by the public in general in this State is deemed to have consented ... [to take certain tests for alcohol, etc.] [Emphasis supplied] It follows that a person who is not driving or attempting to drive on either a highway or private property used by the public in general has given no such consent. Otherwise, a person sitting in a restaurant, a bar, or his own home, could be asked to submit to such testing on penalty of losing his license to drive, whether or not the person had driven at all. Further, regardless of the locale, Transportation Article § 11-114, provides that: "'Drive' means to drive, operate, move, or be in actual physical control of a vehicle . . . ." Additionally, to "operate" is further defined, in a circular fashion, in § 11-141, as "to drive, as defined in this subtitle." There is no evidence in this case that Respondent drove or attempted to drive 30 his vehicle while intoxicated. Respondent testified that he was not driving or attempting to drive at the time of his arrest. [E. 36] Officer Mondini also testified that he never saw Respondent driving the vehicle. [E. 76-77] At the time that the officer approached Respondent, there was no evidence known to the officer that the vehicle had recently been driven to that location by Respondent. Additionally, to the extent that Respondent could be said to have "operated" the vehicle by lowering the power windows, this was done in response to requests by paramedics and the arresting officer. Thus, the issue is whether the arresting officer had a reasonable suspicion that Respondent was in "actual physical control" of the vehicle while intoxicated. In Atkinson v. State, 331 Md. 199, 212-13 (1993), this Court addressed the meaning of the term "actual physical control" of a vehicle. The Court stated: Neither the statute's purpose nor its plain language supports the result that intoxicated persons sitting in their vehicles while in possession of their ignition keys would, regardless of other circumstances, always be subject to criminal penalty. In the words of a dissenting South Dakota judge, this construction effectively creates a new crime, "Parked While Intoxicated." Petersen v. Department of Public Safety, 373 N.W.2d 38, 40 (S.D.1985) (Henderson, J., dissenting). We believe no such crime exists in Maryland. Although the definition of "driving" is indisputably broadened by the inclusion in § 11-114 of the words "operate, move, or be in actual physical control," the statute nonetheless relates to driving while intoxicated. Statutory language, whether plain or not, must be read in its context. NCR Corp. v. Comptroller, 313 Md. 118, 125, 544 A.2d 764, 767 (1988). In this instance, the context is the legislature's desire to prevent intoxicated individuals from posing a serious public risk with their vehicles. We do not believe the legislature meant to forbid those intoxicated individuals who emerge from a tavern at closing 31 time on a cold winter night from merely entering their vehicles to seek shelter while they sleep off the effects of alcohol. As long as such individuals do not act to endanger themselves or others, they do not present the hazard to which the drunk driving statute is directed. Thus, rather than assume that a hazard exists based solely upon the defendant's presence in the vehicle, we believe courts must assess potential danger based upon the circumstances of each case. We therefore join other courts which have rejected an inflexible test that would make criminals of all people who sit intoxicated in a vehicle while in possession of the vehicle's ignition keys, without regard to the surrounding circumstances. The Court adopted a totality of the circumstances test, which should take into account certain factors, including the following: 1) whether or not the vehicle's engine is running, or the ignition on; 2) where and in what position the person is found in the vehicle; 3) whether the person is awake or asleep; 4) where the vehicle's ignition key is located; 5) whether the vehicle's headlights are on; 6) whether the vehicle is located in the roadway or is legally parked. No one factor alone will necessarily be dispositive of whether the defendant was in "actual physical control" of the vehicle. Rather, each must be considered with an eye towards whether there is in fact present or imminent exercise of control over the vehicle or, instead, whether the vehicle is merely being used as a stationary shelter. Courts must in each case examine what the evidence showed the defendant was doing or had done, and whether these actions posed an imminent threat to the public. 331 Md. at 216-17. In Atkinson, the defendant was sitting intoxicated and asleep in the driver’s 32 seat of his vehicle, lawfully parked on the shoulder of the road, with the keys in the ignition but the engine off. This Court held that Atkinson was not in "actual physical control" of his vehicle, as contemplated by the statute. In State v. Love, 182 Ariz. 324, 326-27, 897 P.2d 626, 628-29 (Ariz. 1995), the Supreme Court of Arizona followed the reasoning of this Court in Atkinson in applying a "totality of the circumstances test," rather than a "rigid, mechanistic analysis" of whether a defendant was in actual physical control of a vehicle while intoxicated. The Arizona court stated: Such an approach was recently adopted in Maryland. See Atkinson v. State, 331 Md. 199, 627 A.2d 1019 (Md. 1993). Finding that its legislature did not intend to forbid intoxicated individuals from seeking stationary shelter in their cars, the Maryland court opted for a flexible test by which fact finders could "assess potential danger based upon the circumstances of each case." Id. at 1025-26; see also Cagle v. City of Gadsden, 495 So. 2d 1144, 1145 (Ala. 1986); State v. Lawrence, 849 S.W.2d 761, 765 (Tenn. 1993). Thus, a determination of actual physical control depends on a weighing of the particular facts presented rather than the application of a boilerplate formula. Factors to be considered in any given case might include: whether the vehicle was running or the ignition was on; where the key was located; where and in what position the driver was found in the vehicle; whether the person was awake or asleep; if the vehicle's headlights were on; where the vehicle was stopped (in the road or legally parked); whether the driver had voluntarily pulled off the road; time of day and weather conditions; if the heater or air conditioner was on; whether the windows were up or down; and any explanation of the circumstances advanced by the defense. See, e.g., Atkinson, 627 A.2d at 1027. This list is not intended to be all-inclusive. It merely serves to illustrate that in every case the trier of fact should be entitled to examine all available evidence and weigh credibility in determining whether defendant was simply using the vehicle as a stationary shelter or actually posed a threat to the public by the exercise of present or imminent control over it while impaired. Id. at 33 1028. In this case, Respondent was sitting "slumped" in the driver's seat of his vehicle in the private parking area of an automobile dealership. There was no evidence that the headlights were on or that the vehicle had been recently driven. By the time the arresting officer arrived on the scene, Respondent had already been approached by paramedics, who had requested that he lower the window and speak with them. Respondent lowered the window about one inch in response to this request. [E. 74] Thus, the fact that the engine was running at the time of the officer's arrival on the scene does not indicate that Respondent was attempting to drive. As the officer testified, Respondent's vehicle had power windows. In order to comply with the paramedics' earlier request that he lower the window, Respondent would have had to put the key in the ignition and turn on the power. Under these circumstances, the officer did not have a reasonable suspicion that Respondent had driven or attempted to drive while intoxicated or that he posed an imminent threat to the public by exerting actual physical control over the vehicle while intoxicated. Accordingly, an essential condition precedent for any administrative action was missing in this case. The Administrative Law Judge’s decision was, in the language of the State Government Article, “...unsupported by competent, material, and substantial evidence in light of the entire record as submitted.” Respondent does not suggest, however, that Officer Mondini had no right to 34 approach the parked vehicle and make inquiries. See, State v.Ott, 85 Md..App. 632 (1991), reversed on other grounds, Ott v. State, 325 Md. 206 (1992). This case, however, is more like Reynolds v. State, 130 Md.App. 304 (1999), where the Court of Special Appeals held that the lawfulness of an encounter between a “... citizen and law enforcement officials under the Fourth Amendment turns on the reasonableness of the actions of law enforcement officials, which must be evaluated according to the alternative which is minimally invasive of personal liberties, yet permits officers to carry out their sworn duties when the facts, which have come to their attention through legitimate means, demonstrate the commission of a criminal act or acts.” [Quoted from headnote 1, p. 304]. Reynolds involved a situation where a pedestrian was stopped by police when he attempted to walk away from an approaching patrol car, and the Court of Special Appeals went on to set guidelines on the propriety of stopping him. The Court said, beginning at p. 321, We begin with the proposition that a pedestrian, who has committed no criminal act, has the unfettered right to freedom of movement on a public street without interference from law enforcement officers. In descending order of intrusiveness, these are the requirements for there to be a constitutionally sanctioned interference from law enforcement officers: Stop, Search, or Arrest, Pursuant to a Warrant--Extreme governmental intrusion resulting in possible loss of liberty in addition to temporary restriction of movement--permitted because, in addition to facts tending to establish that a crime has been committed and suspect is criminal agent, neutral arbiter, magistrate, or judge with legal knowledge superior to officer has reviewed facts and indicated opinion that they constitute probable cause. 35 Warrantless Stop, Search, or Arrest--Extreme governmental intrusion resulting in possible loss of liberty in addition to temporary restriction of movement--permitted because of the exigency of a felony having been committed or a misdemeanor being committed in officer's presence, i.e., because of the ability to personally verify the commission of the offense. Stop, Pursuant to Terry v. Ohio--Less intrusive governmental action resulting initially in temporary restriction of movement--permitted when officer observes suspicious activity indicating criminal activity afoot; bases include officer's experience, knowledge of suspect's criminal history, high crime area; officer may conduct limited "pat-down" of outer garments to detect weapons when officer has apprehension for his or her safety. Accosting--Only minimally intrusive governmental action resulting in no restriction of movement--permitted as long as inquiry involves no show of authority and objective circumstances indicate a reasonable person would feel free to leave. [Titles bold in original quote, emphasis supplied to text above.] The Court of Special Appeals went on to say: Although judicial decisions speak in terms of a "mere accosting" being a non-constitutional event, an "accosting" references only the actions of the police without respect to the response of the person accosted. An accosting may continue to be a non-constitutional event if: 1) the citizen consents to answer questions or otherwise cooperates and 2) that consent is not the result of physical force or a show of authority by police signaling that compliance with the requests of law enforcement officers is required. Thus, notwithstanding federal and State decisions that hold an "accosting" is a non-constitutional event, it ceases to be so when the circumstances demonstrate that the purported consensual response of the citizen is the product of coercion. The record in this case demonstrates that Officer Mondini did, indeed make a show of authority and even intruded into Respondent’s car in order to force the door 36 open and the Respondent outside the vehicle. There was no preliminary inquiry concerning Respondent’s name, his reason for being there, or even a request to produce license and registration. And Mondini offered absolutely no respect whatever to Respondent’s assertions that he did not have to roll down his window or get out of the car. Consider, by analogy, the situation where roadblocks are employed in the detection of drunk drivers. This Court held, in Little v. State, 300 Md. 485 (1984), that the reasonableness of this tool depended upon following certain procedures, one of which was to permit motorists not to go through the roadblock itself. This Court describe the procedure, in part, as follows: A motorist wishing to avoid a sobriety checkpoint may make a U-turn or turn onto a side road prior to reaching the roadblock. No action is taken against a driver doing so unless the motorist drives erratically. For example, on several occasions, drivers ran off the road while trying to turn around and they were stopped. Likewise, a driver who stops at the checkpoint but refuses to roll down the car window is allowed to proceed 300 Md., at 492, Emphasis supplied. The present case arguably presents some “facts” known to the officer justifying a concern about the welfare of Respondent or some quantity of suspicion about his use of alcohol. Nevertheless, before Officer Mondini physically intruded into Respondent’s vehicle, he had absolutely no basis whatever to believe that Respondent was driving or attempting to drive that vehicle. To him, merely being in a vehicle with the engine running was enough. [E. 76] His conduct was extreme, and was not undertaken in good faith. Compare, Motor Vehicle Administration v. 37 Richards, 356 Md. 356 (1999), in which this Court held: Although we have concluded that the exclusionary rule of the Fourth Amendment is not applicable in license suspension proceedings under § 16-205.1, we are nevertheless concerned, as in Sheetz and Chase, that our decision today not be abused. We need not, however, dictate an exception to our general rule that the exclusionary rule does not apply in administrative license suspension proceedings, as we found necessary in those two cases with respect to the administrative proceedings *378 involved therein. (FN11) The current statutory and regulatory framework for § 16-205.1 adequately addresses our similar concerns in the present matter. As noted in the State's brief, the MVA accounted for this Court's concerns in Sheetz and Chase by [739 A.2d 71] promulgating COMAR 11.11.02.10H(1) with respect to § 16-205.1(f) hearings. That regulation provides that when a police officer, in obtaining or seizing disputed evidence, acted in bad faith and not as a reasonable officer should act in similar circumstances, the evidence is inadmissible. (FN12) [2] In conclusion, because the exclusionary rule of the Fourth Amendment does not apply in civil administrative license proceedings under § 16-205.1(f), and because the ALJ found the initial stop to have been made in good faith, the circuit court erred in ruling that Respondent's license was not properly suspended for failing to take a chemical breath test when legitimately requested to do so. 356 Md., at 377-378 [Emphasis supplied] The instant case, of course, presents the opposite side of the same coin. Here, an ALJ allowed the action under § 16-205.1 to proceed despite a lack of evidence that Respondent was “driving or attempting to drive” and admitted evidence acquired by a police officer who acted in bad faith, misunderstood the law, and unlawfully intruded into Respondent’s vehicle. The Circuit Court upheld this action by misapplying Atkinson, supra and overlooking the conduct of the officer. This Court should hold that the Officer’s conduct forms a separate and independent basis for 38 overruling the 120-day suspension imposed by the Administrative Law Judge. CONCLUSION This Court should find that Officer Mondini’s contact with Respondent began and ended with impropriety. In a society that values individual liberty, the right to consult counsel, and freedom from unwarranted intrusion, this case cannot be the basis for a license suspension Respectfully submitted, Reginald W. Bours, III REGINALD W. BOURS, III, P.C. 401 East Jefferson Street Suite 103 Rockville, Maryland 20850 Statement Pursuant to Rule 8-504(a)(8) This brief has been prepared using Arial 13-point proportional type and double spacing except where single spacing is permitted. Footnotes were done in Arial 11-point. Titles in the Table of Contents were done in Arial 14-point. 1 APPENDIX Important Documents Enlarged Copy of the ALJ’s Findings of Fact Highlighting the Findings Made With Respect to Counsel [Next Page]