Contracts Outline

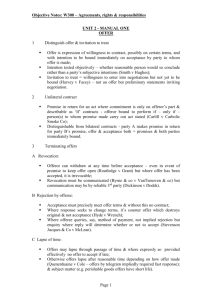

advertisement

Contracts Outline Fall 1998—Prof. Soper Farnsworth text I. CONSIDERATION AS A BASIS FOR ENFORCEMENT 44-55 Consideration: benefit to promisor, detriment to promisee. 1. debt—where someone has gotten something and now enforce the payment of the debt—benefit to promisor 2. covenant—sealing doesn’t help today if there is no consideration 3. assumpsit—must be detriment to promisee Hamer v. Sidway (pg47) (47) (f8)—An uncle promised his nephew $5,000 if he gave up drinking, smoking and gambling until 21. He fulfilled the promise, uncle promised to pay later, he died, executor argued that there was no detriment to promisor because nephew was better off. Court said that he gave up a legal right. Also could argue there was no benefit to promisee, but it could be argued that the uncle did receive a benefit. (If behavior is already illegal, bargain may not be valid. Already required not to do it, so no detriment). §79—Adequacy of Consideration; Mutuality of Obligation If the requirement of consideration is met, there is no additional requirement of: (105) (a) a gain, advantage, or benefit to the promisor of a loss, disadvantage, or detriment to the promisee; or (b) equivalence in the values exchanged; or (c) “mutuality of obligation” Gift Promises (pg52) (49)—reasons for not enforcing: Private (reasons that focus on fairness between the parties) 1. Promisor a) not enriched b) may have acted rashly 2. Promisee a) no harm Public (society) 1. Gifts are sterile transactions in the market 2. Administrative—hard to prove—statement of present intent is very close, but not a promise Executed Gifts—gave the money. Ct says you can’t get it back 1. There is proof of the promise 2. Now we don’t care if you acted rashly Peppercorn Theory (pg54) (68)—The idea that even something trifling in value can be consideration as long as it is bargained for. The courts don’t want to second guess people’s contracts. 1 1. A promises to sell Blackacre for $1 (worth $5000). 2. A promise to sell option to buy Blackacre for $1. (1) looks like you are just trying to turn it into an exchange, so according to §71, may not be consideration. (2) an option can be worth $1, so probably okay. II. FORBEARANCE TO SUE AS CONSIDERATION 55-62 Fiege v. Boehm (pg55)-- promised not to institute bastardy proceedings against if he agreed to pay. After blood tests proved he was not the father, he stopped paying, and she started bastardy proceedings. She tries to recover, and he claims no K because the promise to forbear was based on an invalid claim. Ct says that if she honestly believed that the claim was valid, then a K did exist. There was consideration. Even if it was a worthless claim, he bought peace of mind. see chart (15) (3) (8) Belief / Objective Valid Valid X Invalid X III. Invalid X (if colorable in 1st Restatement ) UNBARGAINED FOR RELIANCE 62-67; 84-98 Feinberg v. Pfeiffer (1962) (pg62 & 104) (16 & 22)-- worked for Pfeiffer for 37 years. President promises to pay her a pension as a reward for her years of service and says that she can retire at any time. She works for another year and a half and retires. She would have worked longer, but the promise was a major factor in her decision. Later, the company stops paying the pension. The ct says she has no right to recover because there is no mutuality of obligation, and her past services are not valid consideration, nor was her continued employment of a yr and ½ . She could have been fired or left the next day. However, the promise was enforceable because she relied on it. (see promissory estoppel) Kirksey v. Kirksey (1845) (pg84) (18)— receives offer from brother-in-law after husband’s death for land if she wants to move. Check first for a bargain—no. Is it a gift? Ct. says yes. Dissent thinks that her loss and inconvenience is sufficient consideration. Today would probably get a different result under §90. Use the up the ante test to find out if it is a bargain. (pg86) 2 Central Adjustment Bureau, Inc. v. Ingram (pg86) (18)—Former employees of CAB left to form their own collection agency in violation of the non-competition contracts they all signed after being hired. ’s argue that there was no consideration because they had already started working. The ct says that continued employment is sufficient consideration to support a non-competition K because they could have been fired. Dissent thinks that additional consideration is necessary, because after employment starts, the ’s have no other options and are forced to sign. ’s bargaining position has been eliminated—like duress. (Promotions are nice, but were not part of the promise). An employer may change the handbook to termination at will provided that the employer gives notice. (pg95—Bankey) IV. RELIANCE AS A BASIS FOR ENFORCEMENT 98-107; 107-116 see chart (21) Contracts 1 6 Promissory Estoppel 1 Estoppel “In Pais” 1 2 2 3 5 6 20th century 5 6 Must have an ind. cause of action Deceit Misrepresentation (broken promise) Material Fact Scienter /intentional Reliance Damage §90—Promise Reasonably Inducing Action of Forbearance 1) A promise which the promisor should reasonably expect to induce action of forbearance on the part of the promisee or a third person and which does induce such action or forbearance is binding if injustice can be avoided only by enforcement of the promise. The remedy granted for breach may be limited as justice requires. 2) A charitable subscription of a marriage settlement is binding under (1) without proof that the promise induced action or forbearance. Ricketts v. Scothorn (pg98) (21)—Granddaughter received a note from her grandfather for $2000 so she would be able to quit her job. She did quit, and her grandfather died, and executor refused to pay claiming no consideration. While there is no consideration (because she did not promise to do anything, and he did not ask her to quit; it was just a gift), she relied to her detriment. 3 Promissory Estoppel (pg101)?? Cohen v. Cowles Media Co. (pg107)—newspaper was supposed to keep his identity confidential. When they didn’t, he was fired. He sued for damages and won. If no bargain, aren’t you relying at your own risk? The point of a promise is to invite reliance What do you have to show under §90? (23) 1. reasonable the promisee would rely 2. the promisee did rely D&G Stout v. Bacardi (pg110) (24)—Stout thinking about selling, but on Bacardi’s assurances they would stay with them, Stout stayed in business. However, Bacardi jumps, and they have to sell for $550,000 less than before. Stout argues that even though Bacardi was not a part of the deal, they relied on the promise to their detriment. Bacardi argues that the relationship is terminable at will, so they relied at their own risk. Stout wins—the ct says that Stout reasonably relied on the promise. Gives reliance, not expectancy (can’t get future profits, only the difference in the sale prices). V. PROMISE FOR PROMISE 116-121; 121-132 Promise for promise is bilateral ($50 to babysit, you say okay) Promise for performance is unilateral ($500 to catch a thief, you say okay, don’t know if you can catch the thief) illusory promise—(19) if the promisor reserves the right to escape performance altogether, then you really haven’t promised anything, and it is not sufficient consideration. There is no mutuality and no K. Horse hypo (wkst)—Seller says promises to deliver horse “unless I change my mind before tomorrow”. Suits by buyer: 1) seller fails to deliver—no recovery, no promise broken 2) buyer relies and incurs costs, still no promise Suits by seller: 3) Buyer reneges before day of delivery—no recovery, no consideration for buyer’s promise (this is the classic case) 4) Seller relies, then buyer revokes—no suit (offer, not a promise) 5) Seller delivers, buyer reneges—seller wins because consideration does exist once seller makes up his mind. If one side has a free way out, then the other side does too. 4 Scott v. Moragues Lumber (1918) (A pg3)—Buyer is lumber co./Seller is ship owner. Seller promises to charge certain amount for charter if he buys a certain ship. No need to decide if promise is illusory because once ship is bought, conditions are met, and buyer wins. Situation #5. Look at the hypos on (28). I don’t understand them. Have to decide if it is illusory if lumber company (buyer) wanted out before seller buys the boat (Sit. #3). May or may not be illusory [why?] 1. If there are other boats out there and it doesn’t matter which one, then the promise is probably illusory. 2. If this is the only boat that will work, then the promise might not be illusory. Strong v. Sheffield (pg119) (20) (29)— promises to forbear suing on debt until he decides to forbear no longer. Illusory, because there is no consideration. She can’t rely on any period of time of forbearance. He actually did forbear for 2 years. Why isn’t this consideration? Ct says that she didn’t want the act of forbearance, she wanted a promise to forbear. [a large discussion in my notes that I should go over pgs29-31] Maetti v. Hopper (pg121) (20) —real estate developer () wants to buy ’s land, but the K is expressly subject to finding satisfactory leases. says she won’t sell. found the leases and paid, but the won’t give the deed. Satisfaction clauses are still consideration because “A promise conditional upon the promisor’s satisfaction is not illusory since it means more than that validity of the performance is to depend on the arbitrary choice of the promisor” (pg123). wins. Satisfaction clauses 1. objective standard—reasonable person 2. subjective—“good faith” satisfaction (honestly not satisfied) how do you show bad faith? - Show you just didn’t like the price - can only get at good faith by proving bad faith Eastern Air Lines v. Gulf Oil (pg125) (21) (33)—Eastern and Gulf had a K for jet fuel. Price should reflect market value. Could get out of the K, but only if they go out of business—easy to see that it is not illusory. K is valid, so should be enforced. [I don’t understand this—study it later] VI. INTERPRETING TO FILL GAPS 133-37; 629-638 5 Wood v. Lady Duff Gordon (pg133) (22) (35)—K gave exclusive right to place her endorsements on products and exclusive right to market her designs and she gets half of the profits. She placed her own endorsements, and sues. argues that it is illusory because he didn’t promise anything. Cardozo says the promise is implied, so there is a K. best efforts v. good faith [what do I do with this?] Zilg v. Prentice-Hall (pg630) (111) (37)—K to publish book about the Dupont family. After problems develop about the nature and the tone of the book, the publisher cuts the advertising budget and reduced the amount of the first printing. Author sues, and ct says that good faith is enough and the initial printing satisfies good faith. (best efforts cannot be everything the author would do, because he’s not paying) (court may have said that you have to give best efforts at first to give the book, then good faith in any continuing efforts. [more in notes when I study] VII. FAIRNESS: CONVENTIONAL CONTROLS 336-348 Reasons to not check for fairness (pg347): 1. no such thing as a just or fair price (especially for unique things) 2. Administrative reasons—costs of courts having to find the price 3. It’s not unfair—you should have check it out. This may be fine in all but the extreme case (“gross disparity”, “shocks the conscience”) McKinnon v. Benedict (pg 337) (61) (40)-- buys land from , makes loan of $5000 if promises to cut down no trees or make improvements in a certain buffer zone for 25 years. paid back the money, and later builds a trailer park. sued for breach. Ct said that inadequacy of the consideration was so gross as to be unconscionable. Detriment to is minimal, but detriment to is severe. Contract is not reasonable. Tuckwiller v. Tuckwiller (pg341) (62) (42)—Mrs. T quits her job to care for Mrs. M. In return, Mrs. M offers to will her farm to Mrs. T. Mrs. M dies before the will can be changed. K is fair and supported by consideration. There was no way for Mrs. T to know how long the obligation would last, so there was great risk on her part. Also, not worried about the disparate value here because Mrs. M can give her farm for nothing to whomever she wants. Have to look at this as the parties did at the time, not in retrospect. Mrs. T gets the farm. 6 Black Industries v. Bush (1953) (pg 344) (63) (43)--, Bush says that the middleman, Black, is making excessive profits in its K with the government, and the K is against public policy. Only void as against public policy if: 1. Contract by to pay for inducing a public official to act in a certain manner. 2. Contract to do an illegal act 3. Contract which contemplates collusive bidding on a public K. This doesn’t fall into one of these categories, so it is valid. To rule otherwise would be to say that all K’s by middlemen are void. VIII. OVERREACHING: CONVENTIONAL CONTROLS 348-361; 361-374 Pre-Existing Duty Rule (pg352)—“Performance of a legal duty owed to a promisor which is neither doubtful nor the subject of honest dispute is not consideration…” §73 Alaska Packers case (pg352) (44)—Workmen signed a K in CA for some work. When they arrived in AK, they demanded a substantial pay increase. Since it was impossible to find new people, the owner signed an agreement. At the end, he only paid them acc. to the first agreement. Ct said the 2nd K was not binding. A new promise for no further consideration and induced by coercion is not valid. Didn’t get anything he wasn’t already entitled to. Classic case of duress. CL never enforced modifications of K’s. People are unhappy with this in the modern context. Schwartzreich (pg354) (45)—Sch. received an offer for a higher salary. He informed his employer and he got a raise. No coercion or duress, but can say that it is just a gift promise. How can you distinguish supplication from clubwielding? 1. say they rescinded the old K and made a new one (that’s what the ct says here) 2. Find anything (a peppercorn, etc) to say they go something. We are using anything to get around the pre-existing legal duty rule, so we need a new rule. (46) §2-209—For modifications, don’t need consideration to be binding. But it must be done in good faith §89 Modification of Executory Contract A promise modifying a duty under a K not fully performed on either side is binding (a) if the modification is fair and equitable in view of circumstances not anticipated by the parties when the K was made; or 7 (b) to the extent provided by statute; or (c) to the extent that justice requires enforcement in view of material change of position in reliance on the promise. NY statute—has to be in writing and “shall not be invalid because of the absence of consideration”, but can be invalid for other reasons, such as duress. SEE THE COMPARING CASES WORKSHEET Arzani v. People (1956) (pg355) (46)—Concrete sub gets an oral promise from the general to pay half of the higher labor costs due to an unforeseen strike. Club wielding, but not with proper means. Ct did not enforce it. Would probably get a different result today. Watkins & Son v. Carrig (1941) (pg357) (47)— found rock during an excavation and said that it would be 9x’s the amount agreed upon; agrees to pay it. argues that the original K was rescinded and a new one took its place. says the other K was not broken, so the second promise to pay has no consideration. Ct enforces the 2nd agreement. Prof: undistinguishable from Arzani. Lingenfelder v. Wainwright Brewery (1891) (B1)—An architect refuses to continue when refrigerator K goes to his competitor. Only resumes work when promises 5% of fridge costs. Not valid. Transaction was the compromise of a doubtful claim. The only difference between the 2 K’s was the additional sum of money. He cannot demand additional compensation. Ct. used the preexisting legal duty rule. Would this be a K under the UCC? Duress? Angel v. Murray (1974) (B4)—Maher is a trash collector for the city. Unexpected increase in the number of dwellings, so he asked for additional compensation, which he was granted twice. General rule—‘A modification of a K is itself a K, which must be supported by consideration’. Modern rule (3 part test—cts should enforce agreements when (1) unexpected difficulties arise (2) during the course of performance, even if no consideration, as long as the parties (3) agree voluntarily. Here we have unanticipated difficulties, before performance complete, and voluntary agreement to pay. Ct. says extra money agreement is binding. Legitimate Reasons (from strongest to weakest) 1. Actual legal defense 2. Colorable legal defense a) good faith belief b) no belief 3. No legal excuse, but claim “hardship” a) unanticipated b) will result in loss? 8 i) ii) iii) loss and put out of business loss, but still profitable just want the money Means Used 1. supplication 2. club-wielding Roth Steel v. Sharon Steel (1983) (B8) (49)—K by Sharon to sell specific amounts at special prices to Roth. Due to federal controls, the market changed, and Sharon couldn’t deliver and was losing money. 2 part test: 1. Whether the party’s conduct is consistent with reasonable commercial standards of fair dealing in the trade. 2. Whether the parties were in fact motivated to seek modification by an honest desire to compensate for commercial exigencies. In this case, it is okay to ask for more money (very liberal), but they did it in bad faith (by threatening to breach), so they lose. Ct doesn’t even reach duress. Is threatening to breach automatic bad faith? no: Carrig (sympathetic to plight) yes: Arzani and Roth See note on Legal-Duty Rule (B16) (50) Pattern I (raise price in 2nd K, refuse to pay) Pattern II (agree to pay less than amt. owed, then try to get whole amt.) It is a lot easier to get out of a K if you haven’t paid yet. After you pay, you must show duress. Austin Instrument v. Loral (pg364) (49)—Loral had a navy K to build radars, awarded a bid to Austin. A 2nd K is not fully awarded to Austin, so they stop delivery under the first K until they get a price increase. Loral checks with all other companies, and no one else can fill the order in time, so they agree to Austin’s demands. Austin’s threat deprived Loral of its free will. Duress (pg365)—a contract is voidable on the ground of duress when it is established that the party making the claim was forced to agree to it by means of a wrongful threat precluding the exercise of free will. A mere threat to breach is not enough for duress. But if you put that with not being able to get the goods from another source, it is duress. 9 Payment in Full Checks (pg371) (pg51)—in some cases, if the creditor accepts the tender of payment, the account is effectively settled and the debtor is discharged of further liability on the account. The rule: if the creditor knows or has reason to know, then it is fine. exception—if it is your money all along, you can take the check and sue for the rest later. UCC 2-311—you have to do your best to bring it to their attention [See notes in this section] (51-53) Flambeau v. Honeywell (1984) (B18) (53)—K can be paid off early, deal included $14,000 worth of computer support. decides its not helpful and pays everything but the computer support with paid in full on the check and in a letter. cashed the check and demanded further payment. Ct. said that it was payment in full, and the owes nothing else even though they paid nothing on the disputed section. 3 rules: (relating to consideration, accord and satisfaction) (B21) 1. compromise in a dispute on entire claim (consistent with CL rule) 2. no dispute, can’t recover—mere refusal not enough 3. no disputed claim, but small dispute on one part—can just pay the undisputed part. IX. NATURE OF ASSENT 138-143; rest 2d 201-203; ucc 2-208; 581-597; 143-152 2 Theories of contract: 1. subjective—meeting of the minds, actual intent 2. objective Knowledge of other’s meaning: A Actual Imputed None B Actual No K A wins A wins Imputed (reasonable) B wins No K A wins None B wins B wins No K Lucy v. Zehmer (pg140) (55)—The seller contracts in jest to sell his farm. The buyer thinks it is real, and there is a signed restaurant ticket. Ct. says he has to sell the farm. Buyer had no knowledge that it was a jest; seller had imputed knowledge. [a little more here] Frigalment v. BNS (pg585) (57)—what is a chicken case. [see my notes]— §2-208— 1) performance 2) express terms 3) course of dealing 10 4) trade usage Ct. says that has the burden and fails to meet it—has to prove that chicken was meant in the narrower sense. Raffles v. Wichelhaus (pg592) (58)—2 ships named Peerless, seller and buyer mean different vessels. When any of the terms used to express an agreement is ambivalent, and the parties understand it in different ways, there cannot be a K unless one of them should have been aware of the other’s understanding. No K. Laserage Tech. v. Laserage Lab. (LTC v. Labs-West) (pg143) (60)—LTC is buying out a disgruntled minority shareholder. K is the settlement agreement. LTC claims no K because they didn’t want him to have shareholder (non-voting) rights—misunderstanding issue. mere memorial v. last clear chance. What did the parties intend? Ct said that he retains the rights and LTC loses [see the 3 reasons on 61—then look at the argument for LTC] Factors to determine whether the parties intended to be bound in the absence of a document (pg150). Look at whether: 1. there is an express reservation of the right not to be bound in the absence of a writing 2. there has been partial performance of the contract 3. all of the terms of the alleged contract have been agreed upon 4. the agreement at issue is the type of K that is usually committed to writing. Sullivan v. O’Connor (pg147 & 7)?? X. THE OFFER 153-163; 163-171; 171-178 §24—Offer Defined An offer is the manifestation of willingness to enter into a bargain, so made as to justify another person in understanding that his assent to that bargain is invited and will conclude it. Corbin says: An offer is an act whereby on e person confers upon another the power to create contractual relations between them. Owen v. Tunison (1932) (pg154) (62)—letters back and forth for the sale of property. Seller says “would not be possible to sell unless I was to receive $16,000”. Buyer accepts, and seller says they aren’t selling. Ct says there was no offer by the seller, so no K. Look at 3 things: 1. language used 11 2. form of communication (#of recipients)—should imply first come first serve 3. context (open terms, prior communications, trade usage) Harvey v. Facey (1893) (pg156) (63)—seller answers an inquiry about how much he would sell for by saying, “lowest price for pen…” This is a harder case because it was in response to an inquiry about how much he would sell for. But the ct still finds no K—he only answered the second question. Fairmount Glass v. Gruden-Martin Woodenware (1899) (pg158) (64)—seller answers a specific inquiry with prices, but doesn’t give amounts. Buyer accepts. Ct. says it is a K. The seller said “for immediate acceptance”, and there is no other way to understand this except as an offer. The seller is therefore bound if the offer is accepted. I. Advertisements—ads are not usually offers to sell because they do not contain sufficient words of commitment to sell (R2d §26, comment b). But if the ad contains a particular number of units in a particular manner, then it may be an offer (ex. first come, first served) (Emmanuel’s pg10). Craft v. Elder & Johnston (1941) (pg163) (65) (28)—advertisement to sell a sewing machine for $26. Customer tries to buy, seller refuses. Ct. says this is not a breach because not an offer, so no K is formed. It is a mere invitation to negotiate. The ct. treats this as very well settled. Lefkowitz (1957) (pg165) (65) (28)—cheap scarves and fur coats…the ct says that where an ad is “clear, definite and explicit, and leaves nothing open for negotiation, it constitutes an offer”. The store claimed there was a house rule to sell to women only, but since the ad did not say that, the wins. The second time, though, he knows about the house rule, so the offer does not apply to him. Because the ad says first come, first serve, we are not reluctant to say this is an offer. If it doesn’t say that, then it may not be an offer, because you can still sell to whomever you want. II. Auctions (UCC 2-328; R2d §28) (67) 1. Advertise 2. Bidders attend 3. Goods put up 4. Bid 5. Hammer Where is the offer and where is the acceptance? #4 and #5—sale complete at fall of the hammer. [ With or without reserve—w/reserve is normal. 12 With means that the auctioneer can withdraw the goods from the sale. So putting them up is not an offer to sell. Without means that there is an irrevocable offer to sell, and the auctioneer cannot withdraw the goods if the bids are too low. Mistaken Bids (pg168) Elsinore Union Elem. v. Kastorff (pg171) (68) (29)—Contractor submitted bid for school, accidentally leaves off the plumbing costs. Ct. holds that he is not held to the original offer. 1. material mistake 2. the other party can be put in status quo 3. unilateral v. mutual mistake (not easy to get out by mutual mistake, but happens) 4. clerical mistakes v. mistakes of judgment (the stupider the mistake, the easier to get out of—people aren’t relying that a clerical error will occur). Is there an implicit promise for the sub to keep the K open? (70) yes— consideration is that I used your bid in my bid. (but the sub doesn’t want the bid used, he wants a job). Is the general bound to use the sub? no, its just an option. XI. THE ACCEPTANCE 179-188; 189-198 (30-33) 2 kinds of contracts: a. Unilateral—only accepted by performance b. Bilateral—accepted by promise or performance §62—acceptance by performance is an implied promise in a bilateral K. [there is so much more in my notes, but I don’t get it] (71-72) Mailbox Rule (pg219-223) (73) (s11)—default rule—favors offeree Accept—effective on dispatch Revoke—effective on receipt In an option K, notice must be received by the 10th day. We distinguish because offeror is the master of the offer. An option K says the offeror can’t revoke, so offeree is in driver’s seat, so only fair to put on offeree and give favor to offeror. International Filter v. Conroe Gin, Ice (1925) (pg180) (73) (31)—There is proposal by seller (not an offer) that has to be approved by an executive officer. The buyer says that it is fine (offer), and the exec officer okays it (acceptance). Two issues: 1) even by your own terms, not an exec officer (ct. says that the president is an exec off.), 2) is saying okay enough acceptance? The acknowledgment sent could serve as notice, but court says that it’s not 13 required. That contradicts §56 which says to accept with a promise, you have to give notice unless it is clearly dispensed with. (§54 says that to accept by performance, no notice required unless requested). White v. Corlies & Tift (1871) (pg184) (75) (32)—Builder tries to accept by performance by buying the materials, but the court says that is not enough of an evidentiary trail; the materials could have used for any job. Tagging or loading onto a truck and showing up are better ways of accepting by performance because there is evidence you intended to perform (“mere preparation v. performance”). Another way to read the holding is that the contract is bilateral because the said that you have to accept between 5-6 by phone. So the offer requests a promise, and the performance is therefore not enough to accept. Ever-Tite Roofing Co. v. Green (1955) (pg187) (76) (32)—the ct. held the offeror must allow a reasonable amount of time to accept by commencing performance. §69—Acceptance by Silence (77) (1) Where an offeree fails to reply to an offer, his silence an inaction operate as an acceptance in the following cases only: (a) Where an offeree takes the benefit of offered services with reasonable opportunity to reject them and reason to know tha they were offered with the expectation of compensation. (b) Where the offeror has stated or given the offeree reason to understand that assent may be manifested by silence or inaction, and the offeree in remaining silent and inactive intends to accept the offer. (c) Where because of previous dealings or otherwise, it is reasonable that the offeree should notify the offeror if he does no intend to accept the offer. (2) An offeree who does any act inconsistent with the offeror’s ownership of offered property is bound in accordance with the offered terms unless they are manifestly unreasonable. But if the act is wrongful as against thofferor is it an acceptance only if ratified by him. 1(a)—if you take the benefit, you have accepted. If you keep it, knowing the price, you have to pay. (if unsolicited merch, though, it is a gift) 1(b)—offeror is being held to the K, silence isn’t usually acceptance in order to protect the offeree 1(c)—custom or previous dealings. Allied Steel v. Ford (pg190) (78) (32)—When an offeree fails to comply with the suggested method of acceptance, but instead begins to perform, is a K formed? Ct. said yes. (different from white because the knew they were accepting). 14 XII. TERMINATION OF THE POWER OF ACCEPTANCE 198-211; 212-219 How can you terminate acceptance? (§33) (pg198) 1. lapse of offer - when it runs out - if not specified, then after a reasonable time 2. revocation by offeror 3. rejection or counter offer by offeree - explicitly - implicitly (won’t pay more than $xx) 4. death (pg218) Option K—a firm offer that includes the promise to keep open for a time UCC 2-205—applies to merchants, in writing, and signed (nothing on consideration. R2d §87—need it in writing, and purported consideration. Toys, Inc. v. FM Burlington (pg202) (83)—option K to renew lease. Where an optionee gives notice of exercising the option buy later disputes the terms of the agreement, may the optionee enforce the option? no [read this case later] Ragosta v. Wilder (pg212) (84)—fork shop case. unilateral K that can only be accepted by performance. Seller revokes before date of performance, buyer sues for breach. Ct. hold there is no breach. [read this later too] Rejection of an Irrevocable Offer (pg217) (85) (36) R2d §37—says that if you have an option K, then you can reject, and still accept within the allotted time. Soper disagrees. You can’t accept, then reject, either. You may have bought: 1. the right to wax hot (accept, then reject) 2. the right to wax cold (reject, then accept) (if he relies, that’s different) 3. the right to decide once and for all (Soper thinks you are here) [ask Al to explain this to me again] XIII. BATTLE OF THE FORMS (2-207) 161-2; 223-226; 226-248 (rev. casebook); (86) (170-177) (38) (11) (s27) Mirror-Image Rule 223-226 “Traditionally, an acceptance must ‘be on terms proposed by the offer without the slightest variation’. Thus the acceptance must mirror the offer, making the offeror the ‘master of the bargain’, such that he can avoid any contract that is not on his own terms” Counter-offers: 1) Rejection and proposal 15 2) 3) (expressly conditional) Neither accept or reject, but risk revocation of offer prob 2, pg216 “I am still considering, but is it possible to get…” Accept with proposal no leverage now, just pleading for different terms Ardente (pg225) (87 & 92) (39) (12)—Buyer wanted furniture to remain with the house. Ct. said that buyer loses because it was not expressly conditional (#2). (Could be #3 because they sent a check and signed.) Last Shot Rule—the last terms win; court assumes that everyone is reading the contracts. In typical battle of the forms, buyer sends form, and seller sends a form back with varying terms. If you apply the mirror image rule, no K. If you apply last shot, you accept seller’s terms by performing. But people aren’t reading these forms, so 2-207 2-207 1) Expression of Acceptance=Acceptance (despite varying terms) unless expressly conditional 2) Additional Terms (between merchants) are part of K unless a) object in advance b) material c) object later 3) Where no K is formed by writings, but conduct shows K. Terms? Those on which both agree, conflicting terms drop out, no last shot rule, code supplies others (i.e. implied warranty). 1) K? despite varying terms? Yeswhat terms? go to 2 Nobut performance, what terms? go to 3 Roto-Lith (1962) (A5) (177) (38,39) (12)—offer to buy cellophane bags. (seller) returned the acceptance and said no warranties. Was the acceptance expressly conditional? Ct. says it is a K, and the last shot rule applies (not knockout like clause 3 says). They resurrected it. The ct. used materiality to decide if it was expressly conditional, and said that the no warranty term was implicitly expressly conditional, but was supposed to look at if it is explicitly stated or if it’s dickered. 16 This decision has been almost universally criticized. Koehring (1977) (A pg7) (39) (12)—telegraph offers back and forth, says “as is, where is”, says specific conditions. Ct. says no K. The replies were not acceptances (although labeled as such), they were rejections and counteroffers. Implicitly expressly conditional—like Roto-Lith, but this time they are dickered terms and 2-207 doesn’t cover dickered terms. Roto-Lith makes sense in this context. If performance, 3 won’t help because if disputed terms drop out, left with no price or delivery method. Now want to say last shot rule. Dorton v. Collins (1972) (C12) (92) (177) (40) (12)—carpet case. (buyer) doesn’t want arbitration, (seller) does. Ct. says that DC got it wrong because they used clause 3 where arbitration dropped out, and buyer won. Instead, this Ct says that “subject to” is not strong enough to make it expressly conditional, so there is a K. Go to clause 2, and ask if arbitration is material. If yes, then no arbitration/if no, then arbitration. Courts are split on whether arbitration is material. Jordan International (1977) (C18) (93) (40) (12)—steel coils case. This time the arbitration clause is part of “expressly conditional” language. It is expressly conditional, so no K. Go to 3, performance, you don’t get arbitration because the disputed terms drop out and it is not supplied by the code. Seller is even worse off here. At least if not expressly conditional (as in Dorton), they could argue the point of materiality. The ct. responds by saying seller can just walk off, and not perform. OR make it expressly conditional up front. Materiality (A8)—Comment 4 suggests that the test is whether the term would constitute surprise or hardship. Ways to make things Expressly Conditional (A10) 1) Pre-printed form (use 2-207 language) (put Jordan and Dorton together. 2) HELP!!!!!! You can make it expressly conditional, but you can’t resurrect the last shot rule. What? Also, what are the 3 tests on A10. I don’t get it!! Knockout Doctrine (C20) Step-Saver (C5)—Step is buying software from TSL and reselling it. Customers are suing SS, who is in turn suing TSL. The box top included no warranty language. SS says that the language materially alters the K they already have, so it drops out. TSL says that there was no K on the phone. The K is when it 17 is purchased. So is it expressly conditional? The court applied the three tests [help...I can’t finish this. I have so many questions] ProCD (1996) (C24) (96)—Database of 3,000 phone books. ignored the license and started selling the information. ProCD proposed a K that a buyer would accept by using the software after having an opportunity to read the license at leisure. Since did not return the goods if terms were unacceptable, he agreed to them. Judge also says this case only has one form so not governed by 2-207. Hill v. Gateway (1997) (C32) (96)—computer ordered over the phone and delivered by mail. A K does not have to read to be effective. People accept the risk of unwanted terms when they do not read the K. There is no reason to require the salespeople to read all the terms over the phone when they can be read and accepted later. ProCD applies, and by keeping the computer for over 30 days, the Hills accepted Gateway’s terms including arbitration. see chart (97) (42) Daitom (1984) (C37) (97)—commercial dryers. read the case, then read my notes. get the three approaches down cold (C43) I get the outcome of the case, I just really need to understand the underlying arguments. XIV. PRE-CONTRACTUAL LIABILITY 248-253; 253-268; 268-285 Davis v. Jacoby (A11) (104)—Husband wants family friends to come care for his wife in an exchange for the estate. A letter is sent (the offer), and the friends sent a letter accepting (acceptance?). The husband committed suicide, cared for the wife anyway. After her death, the will gave the estate to someone else. The lower ct. said that the husband wanted performance, so it is unilateral and the offer expired when he died. This court says it is a bilateral promise because he wanted the promise his wife would be taken care of after his death. They wouldn’t have gotten reliance because they performed after the death of Mr. Whitehead. The reasons given by the court are weak because you may want to know that the carrot is high enough so they will start performance Need to focus on the offeree, not the offeror. But this court focuses on the offeree. Ragosta v. Wilder (pg266 & 212) (107)—unique because it is not to seller’s advantage to have a bilateral K. [look at this] 18 Drennan v. Star Paving (pg253) (105)—sub submitted bid for paving work. General used it and was awarded the K. He went to tell the sub, and before he tells the sub, the sub revokes. The court rejects the idea that there was a promise to keep it open or consideration for that promise and the idea that using the bid is acceptance of a conditional K. But they consider reliance. The difference between §45 and §90 is the remedy. In §45, you get the K, in §90, you get reliance only. If you are a sub, can you avoid §90? Yes, you can say it is revocable at any time, but generals are not likely to use you. Can you say, if you use me, then you have to award the K to me? Yes, you can get a K before the bid is accepted. Lack of consideration is not fatal to a §90 claim. (pg255) §87(2) seem to say that there are offers w/o implied promises to keep them open that you can still rely on. Soper thinks there are none, that at best it is a restatement of §90 Holman Erection v. Orville (pg259)?? (106)—general is not promising to use you. Why might you have a weaker §90 case in Ragosta than Drennan? no implicit promise to keep it open. BUT you were running the risk of someone beating you, not seller revoking. Indefinite (open) terms 1. What did parties intend? 2. What is the court able (willing) to do? Intend Did you intend to be bound? Is the writing mere memorial? a) not bound (until parties decide) b) fully bound (ct. to supply terms if parties can’t) that opens the 2nd question, what are the courts willing to do? see eg. UCC 2-204; 2-305; 2-308; 2-309 c) partially bound—duty to bargain in good faith. Don’t want the court to fill in terms, but still want a remedy if bad faith. a & b are the only ones in the common law. Hoffman v. Red Owl Stores (1965) (pg268) (109)-- wants a franchise. Mutually agreed to invest in small grocery. “Advised” to sell the grocery (loses summer business). Told all along that $18,000 would be enough. put a down payment on a lot in Chilton. Sold the bakery and moved the family to Chilton. Deal fell through because Red Owl kept raising the price and changing the terms. 19 He can’t just sue under K because the terms were never definite (critical open terms pg269) So which of the three is it? b (fill in the terms with other red owl stores) or c (duty to continue to bargain in good faith on the open terms). ran the risk of not being able to agree on layout and rent, but not on how much he contributes To make it a §90 case, have to find #1, no K What was the promise broken? $18,000 is sufficient. Consideration? going and getting experience Why can’t the $18,000 and the experience be a K? because they aren’t bargaining—they just advise. It is a gratuitous promise by Red Owl No consideration, but reliance and you should have foreseen this What would K give in remedies? profits as a red owl franchise [huh]. What is Red Owl’s argument? We didn’t make a promise, just a statement of present position. Some evidence that Hoffman viewed it that way too. He keeps going along until the price gets too high; maybe he knew it wasn’t a promise. Channel Home Centers v. Grossman (1986) (pg272) (112)—easier than Hoffman. Channel signed a letter of intent to rent at the ’s request. Court asks 1) Did both parties intend to be bound? 2) Are the terms of the agreement sufficiently definite to be enforced? 3) Was there consideration? The court answers yes, yes, and the letter of intent was consideration. What shows the promise? 1. the language of the letter, and 2. both took action in reliance. Ct. found a K, duty to negotiate in good faith see another confusing discussion on 112 of my notes. Wheeler v. White (pg271)— promises a loan if can’t get one anywhere else. relies. Court said that critical terms were left open (but they weren’t that critical—shows the reluctance of courts to fill in terms), so no K. But gives him §90 reliance. There was no option of c (partially bound). XV. STATUTE OF FRAUDS 286-290; 294-303 (f9) 5 require writing under the statute. We will use 3: 1) K can’t be performed in a year 2) sales of good over $500 3) K for the sale of interests in land or real estate 3 Questions to ask: 1) Does it fall within the statute? 2) Is it written? 3) If not, does it fall within the exceptions? (2-201) 20 If a lifetime provision, it can be performed in one year if you die, so no writing required. As in Hamer, the letter five years later can be the writing. It doesn’t have to be contemporaneous Don’t need a writing for a 5 year non-competition agreement because if you die, then by definition, you won’t be competing code is more liberal (pg299) §2-201 XVI. INTERPRETATION: PAROL EVIDENCE RULE 565-581; 597-611 (s23) Gianni v. Russell (1924) (pg566) (119)-- is renegotiating his lease with a new owner. He agrees not to sell tobacco as part of the agreement. He claims that the consideration for that is that he has exclusive rights to sell soft drinks, but it is not in the writing. In the lower court, evidence gets in and then Gianni wins. In this court, evidence doesn’t get in. There are two steps: 1) whether the evidence gets in 2) if so, then persuade it is true. Need a good explanation for why it is not in the writing. ex. deeds A contemporaneous letter is fine, only bars contemporaneous oral agreements After the agreement writings and promises are not covered by this; goes into precontractual liability The only reason for parol evidence is evidentiary; no societal reason to make sure you think about the K (unlike Statute of Frauds) see diagram (120) [talk about difference between integrated and not] Williston & Corbin W says look at the final form C says hear all the evidence and then decide Masterson v. Sine (1968) (pg570) (122)-- 21 Bollinger v. Central PA (1967) (pg578) (121)—K for city to do road work. Supposed to recover the dirt. Evidence gets in due to the exception that you can reform the written agreement if it is mutual mistake. Mitchell v. Lath (1928) (pg577) (123) Seagram (pg577) (123) 22