Administrative Office St. Joseph's Hospital Site, L301

advertisement

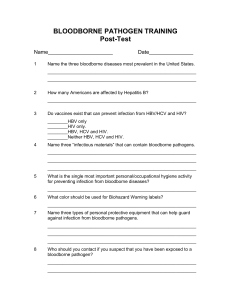

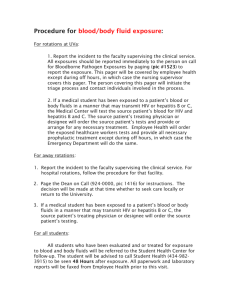

Administrative Office St. Joseph's Hospital Site, L301-10 50 Charlton Avenue East HAMILTON, Ontario, CANADA L8N 4A6 PHONE: (905) 521-6141 FAX: (905) 521-6142 http://www.fhs.mcmaster.ca/hrlmp/ Issue No. 52 QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER August, 2000 OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURE TESTING FOR HEPATITIS AND HIV - WHAT'S NEW? Despite published recommendations to help minimize the health care worker’s (HCW) risk of exposure to fluids capable of transmitting bloodborne pathogens [ie: Hepatitis B Virus (HBV), Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)1,] occupational exposures occur on a regular basis and provide both anxiety for the HCW and a challenge to the laboratory to provide appropriate testing. In 1996, a joint OHA/OMA Communicable Disease Surveillance Protocol for Bloodborne Diseases was developed in response to widespread concern in hospitals about the occupational hazards of HBV, HCV and HIV.2 "Blood and body fluid precautions" which was originally intended for use with known HBV positive patients gave way to an expanded "universal blood and body fluid precautions" in recognition of the fact that HBV status of patients is not always known and the prevalence of HCV and HIV was on the increase. Most hospitals subsequently developed needlestick protocols which varied depending on the opinions and expertise of infection control and occupational health staff/physicians. The escalating HIV/AIDS epidemic, together with the first reported cases of HCW’s found to be infected with HIV resulted in the suggestion that HCW’s should be screened for HIV to ensure the protection of patients. Several lookback studies have now shown that transmission of HIV from a HCW to a patient is extremely unlikely when appropriate infection control practices are followed and the idea of testing HCW’s for HIV has not been pursued. The availability of HCV testing in 1990 and the subsequent Krever Commission investigation into tainted blood ushered in a new awareness of bloodborne pathogens and ensconced HCV as a major risk to HCW’s. Transmission studies for HBV and HIV have indicated that HBV is transmitted much more easily than HIV in a health care setting. For example, after a needlestick injury from a needle contaminated with HBV, there is a 6-30% chance that the victim will be infected. In a similar situation with HIV, there is about 0.4% chance of infection. Recent studies on occupational exposure to HCV indicate an infection rate intermediate between HBV and HIV, in the range of 3-10%. In 1997, Health Canada issued an Integrated Protocol to Manage HCW’s Exposed to Bloodborne Pathogens. 3 The Regional Virology Laboratory (RVL) of the Hamilton Regional Laboratory Medicine Program, located at St. Joseph’s Hospital, has been providing occupational exposure testing for the Hamilton Region for the past 25 years. In the 1980’s before HCV was discovered and HIV had became a significant problem, HBV was the focus of occupational exposure testing. Following exposure to blood or body fluids, the "source" patient is routinely tested for Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) to determine the infectivity status of the donor. If the donor is positive then the HCW should be tested for antibody to HBsAg (anti-HBs) which is the sole marker for immunity. If the HCW is immune (> 10 IU/L anti-HBs) then no further action is required. If the HCW is not immune (<10 IU/L anti-HBs) then Hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) and Hepatitis B vaccine should be offered. In the event that the donor cannot be identified (i.e. needlestick from a discarded sharp or syringe) the donor material should be considered as infectious and the HCW should receive post exposure prophylaxis (HBIG and vaccine) if they are not immune. In 1993 Hepatitis C testing was added to the occupational exposure protocol. Initially only the source was tested for antibody to HCV (anti-HCV) however shortly thereafter testing of the HCW for anti-HCV was initiated for medicolegal reasons (e.g. in the event of a WCB claim). Following infection, seroconversion usually occurs in 5-6 weeks. However, in some cases seroconversion may be delayed for up to 6 months. For this reason HCW’s should be tested at 1 month and again at 6-9 months after exposure to pick up late seroconverters. Although testing for HCV RNA has been shown to narrow the time interval between acute infection and detection of infection in some cases to 1-2 weeks this test is not recommended for occupational exposure due mainly to its increased cost. HCV RNA testing is used to detect infection in immunosuppressed individuals who may have a blunted serological response, including hypogammaglobulinemic patients. There is no prophylactic treatment currently available for HCW’s exposed to HCV; available data do not support the use of immune globulin (IG) or antiviral agents. The HCW should receive counseling from a health care provider and be advised to report any signs of hepatitis-like illnesses. All sera testing positive for anti-HCV antibody by a screening EIA test in Hamilton are sent to the Toronto PHL for confirmation using a second or third generation recombinant immunoblot assay or by an EIA using different HCV antigens from those employed in the screening EIA. Guidelines for post-exposure management of HCW’s exposed to HIV were issued by LCDC in 1990. 4 HIV antibody testing following exposure to blood or body fluids is now recommended practice. The availability of effective anti-retroviral agents for preventing infection in exposed HCW’s provides a strong rationale for HIV testing of the donor. Post-exposure prophylaxis must however be given within the first 2 hours of exposure and this presents a number of logistic hurdles. An occupational exposure is investigated by submitting a serum to the Virology laboratory at St. Joseph’s Hospital for HIV testing. The request must be accompanied by signed consent. The laboratory is currently providing a 24-hour turnaround-time for results and sera positive for HIV antibody are sent to Toronto for confirmation by Western blotting. HCW’s exposed to HIV contaminated blood or fluids should complete a course of medications and be followed for 6 months for seroconversion. Given the very low probability of seroconversion after 6 months and the unnecessary anxiety caused by extending the testing period beyond 6 months, testing at 12 months is not recommended. HCW’s started on post-exposure prophylaxis can be taken off medications if the donor tests negative for HIV antibody. As rapid tests (15-20 min) are approved and implemented the turn-around-time may improve and HCW’s may be spared unnecessary prophylaxis. REFERENCES: 1. LCDC. Infection Control Guidelines: preventing the transmission of bloodborne pathogens in health care settings. CCDR 1997. 2. OHA/OMA Communicable Disease Surveillance Protocols Bloodborne Diseases. 1996, pp1-12. 3. LCDC. An integrated protocol to manage health care workers exposed to Bloodborne pathogens. CCDR 1997; 23 S2:1-18. 4. LCDC. Guidelines for counselling persons who have had an occupational exposure to HIV. CCDR 1990; 16 S2:1-12. Dr. J. Mahony, Head of Virology Services St. Joseph's Hospital, Hamilton Regional Laboratory Medicine Program Professor of Pathology and Molecular Medicine