MicrosoftWord version

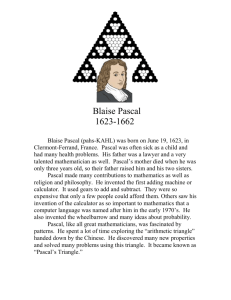

advertisement