TA QUESTION OF THE MONTH

advertisement

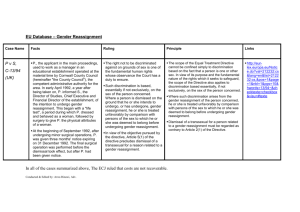

TA QUESTION OF THE MONTH on Reassignment to Another Job as an Accommodation FEBRUARY 2004 Prepared by the Disabilities Law Project & the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law Q. My client is no longer able to perform his job as a driver for a national delivery service because of worsening osteoarthritis. My client asked for reassignment as an accommodation. The employer had a job opening in its customer service department and allowed my client to apply for it. My client met the minimum qualification standards (high school diploma, six months of customer service experience, and a neutral reference from his prior employer), but the employer offered the job to a person with a college degree, two years of customer service experience, and exceptional references. Since the employer had no other present openings, my client lost his job. Does my client have a claim under the Americans with Disabilities Act for failure to make a reasonable accommodation? A. The question of whether the ADA requires an employer to offer an open position to an employee with a disability who meets the job’s minimum qualifications, as opposed to whether it must simply allow the employee to compete for the job, is at present unsettled. Based on current case law, for example, the employee would likely prevail in the Tenth Circuit and lose in the Seventh Circuit. Elsewhere, success would likely depend on whether the employer has an established policy of hiring the most qualified applicants. This Q&A briefly explores the background of reassignment as an accommodation under the ADA; the EEOC's position on whether an employee must be offered a reassignment if he is qualified; and the diverse positions of the courts on the issue. 1. General Principles Relating to Reassignment as a Reasonable Accommodation An employer covered by Title I of the ADA must make reasonable accommodations unless doing so would impose an undue hardship on the operation of the employer's business. 42 U.S.C. §12112(b)(5). The statutory definition of the term "reasonable accommodation" expressly identifies "reassignment to a vacant position" as a potential accommodation. 42 U.S.C. §12111(9)(B). Congress explained its inclusion of reassignment as a potential accommodation by noting that "a transfer to another vacant job for which the person is qualified may prevent the employee from being out of work and [the] employer from losing a valuable worker." H.R. Rep. No. 101-485(II), at 63 (1990), reprinted in 1990 U.S.C.C.A.N. 303, 345. In general, reassignment is the accommodation of last resort, and it should be considered only if accommodation within the employee's current position would pose an undue hardship. See 29 C.F.R. Pt. 1630, App., §1630.2(o); Cravens v. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas City, 214 F.3d 1011, 1019 (8th Cir. 2000). An employee with a disability who is able to perform the essential function of his job, but whose job is eliminated for other reasons, is not entitled to reassignment. Aponte Diaz v. Navieras Puerto Rico, Inc., 130 F. Supp.2d 246, 254 (D.P.R. 2001). The employee must be qualified for the reassigned position. 29 C.F.R. Pt. 1630, App., §1630.2(o); EEOC, Enforcement Guidance: Reasonable Accommodation and Undue Hardship Under the Americans with Disabilities Act (1999) (hereinafter Reasonable Accommodation Enforcement Guidance); Hedrick v. Western Reserve Care System, No. 023898, 2004 WL 43163 at *9 (6th Cir. Jan. 9, 2004). The employer need only consider reassignment if the position is vacant within a reasonable amount of time. 29 C.F.R. Pt. 1630, App., § 1630.2(o); Reasonable Accommodation Enforcement Guidance. The employer need not create a new job or a vacancy for purposes of accommodating an employee with a disability. Smith v. Midland Brake, Inc., 180 F.3d 1154, 1174 (10th Cir. 1999) (en banc) (collecting cases). The reassignment should be to an equivalent position in terms of pay, benefits, and status. 29 C.F.R. Pt. 1630, App., § 1630.2(o); Reasonable Accommodation Enforcement Guidance. In the absence of vacant, equivalent positions, however, the employer can offer reassignment to a lower-graded position. 29 C.F.R. Pt. 1630, App., §1630.2(o); Reasonable Accommodation Enforcement Guidance. The employer is not required to offer a promotion. 29 C.F.R. Pt. 1630, App., §1630.2(o); Reasonable Accommodation Enforcement Guidance. If an individual rejects a reasonable accommodation, including a valid reassignment, he will no longer be considered a qualified individual with a disability. Hedrick v. Western Reserve Care System, 2004 WL 43163 at *9. 2. The EEOC's Position on the Right to Reassignment The EEOC's position is that reassignment does not mean that an employee is merely entitled to compete for a vacant job opening. Reasonable Accommodation Enforcement Guidance (Question 29). Rather, the EEOC has written: "Reassignment means that the employee gets the vacant position if s/he is qualified for it. Otherwise, reassignment would be of little value and would not be implemented as Congress intended." Id. (emphasis in original). Since a person with a disability always can compete for a vacant job, the EEOC reasoned that Congress's identification of reassignment as a reasonable accommodation would be a nullity if it provided no more than that which would have existed without the ADA. Id. (Question No. 29 n.87). 3. The Courts' Assessment of the Right to Reassignment Although not directly on point, the Supreme Court's decision in US Airways, Inc. v. Barnett, 535 U.S. 391 (2002), must be considered in assessing this issue. In that case, the Court was presented with the question of whether reassignment can be a reasonable accommodation when reassignment contravenes an employer's established seniority system. Initially, the Court rejected the defendant's assertion that the ADA can never require an employer to waive disability-neutral workplace rules. Id. at 39798. "The simple fact that an accommodation would provide a ‘preference" – in the sense that it would permit the worker with a disability to violate a rule that others must obey – cannot, in and of itself, automatically show that the accommodation is not ‘reasonable." Id. at 398 (emphasis in original). Nevertheless, the Court concluded that, "in the run of cases," it would not be reasonable to reassign an employee with a disability to a vacant position if doing so would contravene an established seniority system. US Airways, Inc. v. Barnett, 535 U.S. at 403-06. The Court cited the importance of seniority to employee-management relations. Id. at 403. The "seniority system provides important employee benefits by creating, and fulfilling, employee expectations of fair, uniform treatment. These benefits include ‘job security and an opportunity for steady and predictable advancement based on objective standards.'" Id. at 404 (citation omitted). The Court left open the possibility that a plaintiff might show "special circumstances" that warranted an exception to the seniority system (e.g., if he could show that the employer often made exceptions to the system), and, if such circumstances were to exist, then reassignment might be a reasonable accommodation. Id. at 405-06. Several lower courts have extended this concept beyond seniority systems. These courts have indicated that employers need not waive legitimate, non-discriminatory employment policies or displace other employees' rights in order to accommodate a disabled employee through reassignment. See Hedrick v. Western Reserve Care System, 2004 WL 43163 at *9; EEOC v. Humiston-Keeling, Inc., 227 F.3d 1024, 1028 (7th Cir. 2000); Cravens v. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas City, 214 F.3d at 1020; Felix v. New York City Transit Auth., 154 F. Supp.2d 640, 659 (S.D.N.Y. July 16, 2001), aff'd on other grounds, 324 F.3d 102 (2d Cir. 2003); cf. Daugherty v. City of El Paso, 56 F.3d 695, 700 (5th Cir. 1995) ("we do not read the ADA as requiring affirmative action in favor of individuals with disabilities, in the sense of requiring that disabled persons be given priority in hiring or reassignment over those who are not disabled."), cert. denied, 516 U.S. 1172 (1996). In EEOC v. Humiston-Keeling, Inc., the Seventh Circuit expressly rejected the EEOC's position that the ADA required reassignment of an employee with a disability to a vacant position for which he was qualified even though other applicants were more qualified. 227 F.3d at 1027-29. Judge Posner wrote that the EEOC's "interpretation requires employers to give bonus points to people with disabilities, much as veterans' preference statutes do." Id. at 1027. The court concluded that "requiring employers to hire inferior (albeit minimally qualified) applicants merely because they are members of such a group ... is affirmative action with a vengeance. That is giving a job to someone solely on the basis of his status as a member of a statutorily protected group." Id. at 1028-29. The court also dismissed the argument that the reassignment duty would be meaningless if it only meant that the employee had to compete for vacant jobs since it still requires the employer to consider the possibility of reassignment and offer the job to the employee with the disabilities if there is not a better candidate. Id. at 1027. The Seventh Circuit re-affirmed this ruling Mays v. Principi, 301 F.3d 866 (7th Cir. 2002), finding further support in the Supreme Court's ruling in US Airways, Inc. v. Barnett. In Mays, the court rejected the plaintiff's argument that she was entitled to a reassignment, concluding: "[A]ssuming that she were qualified for such a job, if nevertheless there were betterqualified applicants – and the evidence is uncontradicted that there were – the [employer] did not violate its duty of giving the job to them instead of to her." Id. at 872. The court explained: [US Airways] holds that an employer is not required to give a disabled employee superseniority to enable him to retain his job when a more senior employee invokes an entitlement to it conferred by the employer's seniority system. [citation omitted] If for "more senior" we read "better qualified," for "seniority system" we read "the employer's normal method of filling vacancies," and for "superseniority" we read "a break," US Airways becomes our case. Id.; accord Vinson v. Grant/Riverside Methodist Hospitals, No. C2-99-1358, 2001 WL 1681125 at *15 (S.D. Ohio Aug. 30, 2001); see also Hedrick v. Western Reserve Care System, 2004 WL 43163 at *10 ("Although WRCS may have had an obligation to reassign her to a vacant position for which she was qualified, the ADA does not mandate that she be afforded preferential treatment."). In contrast to the Seventh Circuit, however, the Tenth Circuit has concluded that "‘reassignment' must mean more than the mere opportunity to apply for a job with the rest of the world." In Smith v. Midland Brake, Inc., the court explained that "if the reassignment language merely requires an employers to consider on an equal basis with all other applicants an otherwise qualified existing employee with a disability for reassignment to a vacant position, that language would add nothing to the obligation not to discriminate, and would thereby be redundant." 180 F.3d at 1164-65. Relying on the EEOC's position, id. at 1166-67, the court wrote: If a disabled employee had only a right to require the employer to consider his application for reassignment but had no right to reassignment itself, even if the consideration revealed that the reassignment would be reasonable, then this promise within the ADA would be empty. The employer could merely go through the meaningless process of consideration of a disabled employee's application for reassignment and refuse it in every instance. It would be cold comfort for a disabled employee to know that his or her application was "considered" but that he or she was nevertheless still out of a job – a job to which he or she had a reasonable claim to reassignment. We do not think Congress intended such a hollow promise when it listed reassignment as one of the specific reasonable accommodations in 42 U.S.C. §12111(9). Id. at 1167. The majority expressly rejected the dissent's assertion that its analysis imposed an "affirmative action" standard, concluding that Congress intended such reassignment as a reasonable accommodation and deemed the failure to provide such accommodation to constitute unlawful discrimination. Id. The court, however, acknowledged that reassignment might not be a reasonable accommodation if it would violate important employer policies (such as seniority). Id. at 1175-76. The court, though, implicitly held that reassignment as a reasonable accommodation would trump a policy of hiring the most qualified person. See also Aka v. Washington Hosp. Ctr., 156 F.3d 1284, 1304 (D.C. Cir. 1998) (en banc) (noting prior to Barnett in the context of a case involving waiver of a collective bargaining agreement provision that "the word ‘reassignment' must mean something more than allowing an employee to apply for a job on the same basis as everyone else ...."). Although the Seventh and Tenth Circuits have squarely addressed the issue of whether employers must reassign employees with a disability who are less qualified than other applicants, the law elsewhere is less certain. An employer might argue that U.S. Airways v. Barnett should be extended to apply to protect policies of hiring the most qualified applicant (and, therefore, an employee who is not the most qualified cannot be reassigned to an open position). An employee, however, could assert that U.S. Airways v. Barnett is inapplicable outside the seniority context since concerns about certainty and expectations in the advancement process that are protected by seniority rules are not present when the issue is determining who is the most qualified. Even if the basic principle of U.S. Airways v. Barnett is extended to these circumstances, it will still be easier for an employee to establish “special circumstances” in this context than in the seniority context. Factors used by most employers to assess applicants often are subjective (e.g., quality of work, personality, references). If an employer considers these types of factors, it will be easier to prove that it does not always adhere to a policy of hiring the “best” candidate based on purely objective criteria. If that is the case, then allowing reassignment of an employee to a job for which he is qualified (albeit, perhaps, not “best qualified”) will not disrupt settled expectations and the employee can make a case that “special circumstances” exist to disregard the employer’s “policy.”