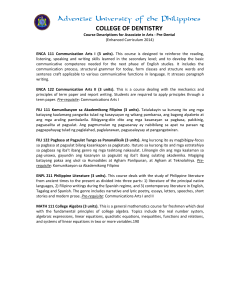

theme 4 responding to society

advertisement