sagip o huli?

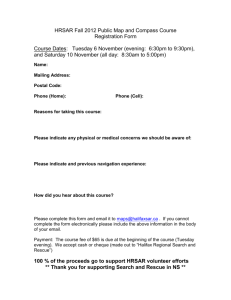

advertisement