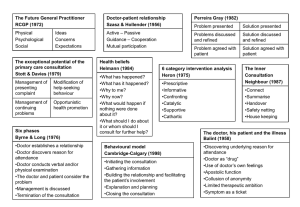

Common MEQ Scenarios

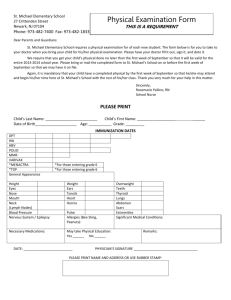

advertisement