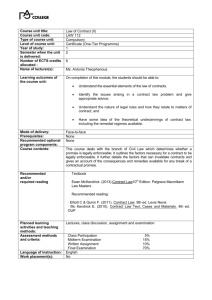

Contracts_Outline_-_Fall_2005_[Lawrence]

advertisement

![Contracts_Outline_-_Fall_2005_[Lawrence]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008494522_1-c1fe2451f8a8de1fd2739f0e8c730b6c-768x994.png)