The photograph's position is often a secondary line of enquiry by the

advertisement

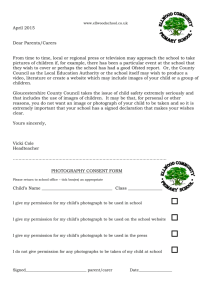

C L A S S I C A L R E C E P TI O N S I N L A TE T W E N TI E T H C E N T U R Y D R A MA A N D P O E TR Y I N E N G L I S H ESSAYS ON DOCUMENTING AND RESEARCHING MODERN PRODUCTIONS OF GREEK DRAMA: THE SOURCES ESSAY 7: THEORY AND PRACTICE IN RESEARCHING GREEK DRAMA IN MODERN CULTURAL CONTEXTS: THE PROBLEM OF THE PHOTOGRAPHIC IMAGE Carol Gillespie (2007) The aim of this paper is to contribute to the discussion about the importance of primary sources in the research and documentation of modern performances of Greek drama by focussing on the use of still photographic images.. The context is our work in the Open University research project on the Reception of Classical Texts in English from the mid-1970s to the present. The first phase of this research has investigated the processes of performance creation in productions of Greek drama on the modern stage and this has underpinned our annotated database of recent examples published on the project website (www2.open.ac.uk/ClassicalStudies/GreekPlays). This focus on process is derived from our view that why, how and for whom the performance is created shapes its relationship with the ancient text and its performance tradition. Researching modern productions means that we have to try to seize information that would otherwise be ephemeral. Our overriding aim in the database is to provide the cultural historians of the future with detailed evidence about the extraordinary impact of Greek drama in the last part of the twentieth century. As this research is carried out in a department of classical studies not one of theatre studies, we have a particular interest in the relationship between the ancient text and its modern interpretations. The hermeneutics has to take account of the nature and dynamics of the modern staging. Whether the performance is in the original Greek or is a translation, classicists have to accept that the relationship between ancient and modern can never be purely linguistic. Even if the modern writer works using a close translation (and increasingly this is used as a mediating stage between the Greek text and the creation of the new play text), there is a further process of translation to the stage. This is shaped by a variety of factors, verbal, non-verbal, cultural and environmental as well as by the subjectivities of the practitioners. Just as the translation, rewriting or play text is part of a modern theatrical environment, so was the ancient text a part of its environment. Through our research, we try to identify and analyse correspondences, or lack of them in the political, cultural and religious settings, the theatrical conventions, theatrical space, the provenance of the audiences and their response. Visual records are a particular concern. Important research has been done on the relationship between Greek vase-painting and theatrical performance in the ancient world.1 Modern images, whether still or moving, may apparently be more intimately connected with a particular performance than are ancient images on painted pottery or mosaics, but are just as problematic in themselves as are the ancient. They present the added difficulty that they involve modern technology as well as an aesthetic and material context that inevitably shapes what they show, how they show it and to whom. The rest of our paper will focus on one kind of visual primary source – the still photograph. Our project is addressing this issue in two ways. We are compiling a photo-gallery of stills, which we shall make available on-line to researchers. We hope that this www2.open.ac.uk/ClassicalStudies/GreekPlays Essays No. 7, 2005 Carol Gillespie gallery be particularly useful in enabling researchers and students to access material from the lesser-known productions that are not extensively featured in the national and international press and are not usually from companies that keep archives. Such productions are nevertheless very important as sources of data which is significant for researching trends in theatre, aesthetics and cultural politics. This essay, seventh in a series of critical essays on the use of primary sources, represents a first step in the a critical evaluation of the potential and the drawbacks of using photographs. We regard it as very important for researchers to make clear what kinds of evidence they are using when they comment on performance. We also want to develop a critical commentary on this evidence to go alongside our database of examples as no database is neutral. In assembling a photo gallery of examples and developing a critical evaluation of the use of photographs as primary sources, we are also addressing the paradox that we write about ‘performances’ without actually having the performance in front of us as a text we can ‘hold’ other than in the memory or the imagination (concepts which need further examination in the context of theatre research; a topic for a future essay). We are constantly thinking about what the photograph can do and what it cannot do in the retrospective construction of performance. Using photographs The positive aspect of using still photographs as primary sources are: i. They contribute evidence from less well-known productions. However, this may not be from actual performances (i.e. photographs may be posed or intended as publicity) NOR can single photographs indicate the changes that take place as the run progresses, although a dated series of actual production photos can be helpful in that respect; ii. They indicate style, physicality and gesture but cannot represent wider movement; iii. They can capture the emotional and sometimes spatial relationship of one actor to another, but only at a particular moment, and within a particular perspective; iv. They focus on details, for instance of costume or make-up or mask, but the viewer cannot know what is on the periphery or the relationship of the parts to the whole; v. With other evidence, the type and style of the photographs suggest what the company wanted to create as its image and how it wanted the performance to be represented (for example art photos? Sexy? Grainy? Key scenes selected? Key actors? Individual? Group?). It is clear then, that using photographs as evidence of aspects of performance is likely to be problematical. A contributing factor to the problem is that in modern industrialised societies we are all involved in the medium of photography at some stage – if not as a producer then as a subject or viewer, or a combination of all three – and many institutions are dependent upon it (the fashion and sex industries, the tabloid press, certain parts of the legal and penal institutions etc.) Yet, comparatively few academic researchers in the UK, outside the area of Art History, receive any formal training in visual analysis. Such an omission means that researchers sometimes treat the performance photograph as the product of a technical and scientific process, capable of depicting objective truth. However, the multi-function characteristic of photography (which enables it to, for example, sell cars, give an insight into the imagination of an artist, identify a ‘criminal’ or capture a personal memory) should alert researchers to the possibility that there are specific discourses at work within photography which allows individual photographs to be ‘read’, and to mean something to someone, within concrete www2.open.ac.uk/ClassicalStudies/GreekPlays 2 Essays No. 7, 2005 Carol Gillespie and delimited conditions of use (that is, meaning can be related to both the original context, or to a new context within which it is viewed). Therefore, as with any other form of documentary evidence, the context of the original is crucial, and yet we often find performance photographs (indeed, most photographs!) being used or displayed in textbooks, academic journals and archives, with very little attempt to contextualise them. The performance photograph then, like any image, is the product of a set of conventions. Those conventions are based on a set of ideas about what the photographer thinks he or she is doing, and a set of practices and procedures that give expression to those ideas. The researcher must therefore remain aware that the performance photograph is neither a factual nor a neutral recording of a particular moment during a production but a personal artistic representation or interpretation by the photographer and/or other agents involved (such as, for example, marketing). The performance researcher therefore has to be able to handle both the evaluation of the photograph as documentary evidence and also the critique of the image as an art form and to form a judgement on the interrelationship between the two spheres. The researcher has to start by asking some basic questions: – Who took the photograph? When? Where? Under what conditions? For what purpose? Who commissioned it? How was it actually used? – What is the place of the image in the photographic context, technical and artistic and/or commercial tradition? (this is important in order to compare with the context and tradition of the performance, and with the artistic and commercial environment external to the performance.) – For comparative purposes: can photos help with study of different productions/adaptations of the same play? (Different character roles/same actor; different productions of Greek plays by the same director/designer/costumer etc.) When applied to the analysis of performance-related photographs from the three separate productions of modern performances of ancient Greek tragedy that are discussed below, such basic questions are crucial. Photographs as records The performance photograph is seen, correctly, as a reference to a record of some prior existence of the performance but this takes us to one of the complexities of using the photographic image as a documentary evidence – the photograph has power precisely because it appears to provide an ‘experience’ of the performance, it gives a sense of bringing the performance back to life. But in retrieving one or more fragmentary glimpses of a past performance the researcher can still only imagine such aspects as gestures, how the performance space was used or features of design/costuming. The problem is compounded because the photograph’s position is often as a secondary line of enquiry– brought out to support or ‘prove’ what has already been decided through other types of research. This leads to photographs being selected from an archive because of some aspect of subject matter contained within the image – an item of clothing, a gesture, the positioning of the chorus – since photographs appear to offer ‘evidence’ that can illustrate the point being made. This leads to the real danger that the viewer of the photographic image comes to identify with the camera and the institution of photography, to such an extent that ‘all other forms of telling and remembering’ begin to fade. (Sekula 1999:187) For example, a researcher might, having already concluded through other areas of research that Theatre Cryptic produces avant garde, modern productions of the ancient plays, be tempted to ‘prove’ their conclusion by using an image from a www2.open.ac.uk/ClassicalStudies/GreekPlays 3 Essays No. 7, 2005 Carol Gillespie newspaper preview of Theatre Cryptic’s performance of Electra at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in August 1999. The production used a new version of the Electra story written by Clare Venables and subtitled ‘Queen of Revenge’. The newspaper photograph (The Scotsman, 19th August, 1999) is a head and (bare) shoulders shot of Electra (Kate Dickie). Her head is a shaven and the word ‘revenge’ is clearly seen tattooed across her skull. Contact with Theatre Cryptic produced another photograph. This time it is a full length photograph, apparently shot on stage, showing Electra (still Kate Dickie) in a long flowing dress and – short cropped hair. Interestingly, Theatre Cryptic were unable to confirm whether or not the full-length image was taken during a live performance, a rehearsal or for another purpose, though they could confirm, from memory, that Electra had short hair for the performance run. Indeed, our original interest in the problem was triggered by the recollection of the researcher who had attended the performance that we documented for our database (DB no. 1115). But which photograph will we rely on some years hence when there is noone left who can remember the performance? This illustrates two problems. Firstly, that performance photographs when uncritically used can be misleading in terms of the performance itself. Secondly, that visual images seldom remain together with detailed contextual information and archivists need also to be aware of this responsibility when compiling collections of images. These two problems demonstrate how crucial our research questions are: what are the photographs’ original conditions of production and, what is the place of these particular images in the photographic context, technique and artistic and/or commercial tradition? In the case of Theatre Cryptic’s Electra photographs, one possibility is that they were posed – possibly for promotional purposes. The head and shoulder shots (which also appeared, though from a different angle, on the front and back of the theatre programme) are dramatic and eye catching and probably tell us more about the company’s desire to draw in an audience than about the actual performance. This is evidence that performance photographs arise not just from the documentary genre but also from the advertising genre. This brings into question the photographer’s role – is s/he a free and creative individual or simply technical labour following orders from two clients (i) the advertising agency who employs the photographer, and in turn relies on the photographer to be successful in each session and therefore bring more work to the agency and (ii) the agency’s client (the theatre company) who have the power to withdraw their patronage of the agency if they are unhappy with the photographer’s work. The researcher must therefore also take into account institutional determinants which might have contributed to the style and content of the photograph. However, the full length photograph, whilst giving the appearance of being taken from the actual performance might also have been self-promotional – perhaps specifically taken for inclusion in Kate Dickie’s portfolio. Some years into the future such a photograph might become part of another genre – that of photograph as art – a photograph ‘by’ rather than a photograph ‘of’. This phenomenon of photograph ‘by’ was noted by Douglas Crimp in the early 1980s who argued that if “photography was invented in 1839 it was only discovered in the 1960s and 1970s” (Crimp, 1993:66-83). He cites the example of Julia Van Haaften’s reorganization of the New York Public library in which she searched through books on disparate subjects (transport, fashion, portraiture etc) for now ‘famous’ art photographers and placed the books under the single category of photography. By separating the photograph from its subject a fashion book containing photographs of Diors’ New Look in 1947 become photographs by Irving Penn, portraits of Delacroix and Manet become photographs by Nadar and Carjat’. The separation of the photograph from its original context clearly alters or www2.open.ac.uk/ClassicalStudies/GreekPlays 4 Essays No. 7, 2005 Carol Gillespie represses the photograph’s information function and points the viewer towards notions of authorship and oeuvre. The role of the archivist With the advent of on-line searchable databases, such as our own, it could be that separation of the photograph from its subject might become, in some ways, less of an issue because it is the user who decides whether or not to search by photographer, performance or actress, and thereby creates the grouping whether it be that of authorship, oeuvre, content etc. But this leaves the onus very much on the archivist to provide details of the original context to ensure the researcher is able to read the image critically. Investigation of a performing arts library that has recently placed its database of images on-line (www.arenapal.com/) demonstrates that context is still not considered an important issue when cataloguing and storing photographs. Photographs in the Arena Pal database are accompanied by only minimal information. [photo image] HECUBA - New version by Tony Harrison Albery Theatre - London 04 / 05 Dir: Laurence Boswell VANESSA REDGRAVE - Hecuba RSC Season Credit: Marilyn Kingwill / ArenaPAL Filename arp1055592.jpg Uncompressed size 2960 Kb File Size 299.09 Kb Dimensions (pixels) 1134 x 891 File Type Image Last Modified 4/22/2005 11:35:59 AM Image Notes: Dimensions 9.60 x 7.54 cm / 3.78 x 2.97 inch Resolution 118.11 ppc / 300.00 ppi Color space RGB Keywords Information Object Name: Category: Supplemental Category: Byline: Credit: ArenaPAL Source: Copyright String: Byline Title: Caption Writer: Headline: Special Instructions www2.open.ac.uk/ClassicalStudies/GreekPlays 5 Essays No. 7, 2005 Carol Gillespie As can be seen from the above screenshot of the entry for a photograph from the 2005 RSC Hecuba production in London (showing Hecuba being held by members of the Chorus) available information includes: production title, date of production run, venue, photographer’s name, name of the main character role and actors name depicted in the photograph, but chorus or other members of the cast ‘around’ the main actors are unnamed. Important categories such as ‘Keywords’, which aids the search facility on databases, and ‘Information’, which could contain crucial contextual information are left blank. (This is also a noticeable contrast with the care taken to give full technical details.) Arena Pal is a commercial database from which it is possible to purchase theatre photographs. The lack of contextual information is therefore particularly dangerous as, when parted from its original context, the meaning in photographs may be altered by individuals or institutions that purchase them and then have the power to define and organise the rhetoric of photographs through the way in which they are displayed, viewed, catalogued. This means that not only are the photographs literally up for sale but also ‘their meanings are up for grabs. New owners are invited, new interpretations promised.’ (Sekula 1999:189). The history of an image and its influence To explore just what can happen when images are ‘sold-on’ we need first to briefly examine the critical reaction to two different productions – the 2005 Royal Shakespeare Company’s Hecuba (translator Tony Harrison) and the 1994/5 National Theatre’s production of The Women of Troy (translator Kenneth McLeish) – before examining a different set of images used the Hecuba theatre programme. Analysis of the RCS’s Hecuba performance text (published by Faber, 2005), shows that Harrison closely followed Euripides’ text. 2 Yet, as Lorna Hardwick noted in a paper to the British Classics Conference (2005) many critics persisted in saying that images in the production ‘looked like photos of Iraq’ (Hardwick 2007). Certainly there were correspondences in the production to the war in Iraq – for example one of the Greek Commanders adopted an American accent, and the phrase ‘coalition forces’, appears in the text a number of times. Such correspondences with contemporary idioms are hardly unusual in translations intended for the immediacy of theatre. One example is the 1994/5 production of Euripides’ The Women of Troy, which used a new translation by Kenneth McLeish and was performed at the National Theatre, London. During the 1980s and much of the1990s wars and social upheaval were occurring in Northern Iraq, Chechnya and the Balkan States. Reviews of the production referred to the ‘Jet fighters and helicopters roaring above’ (John Peter, Sunday Times, March 26, 1995), a ‘set with steps of jagged concrete, wire mesh and corrugated iron suggestive of a prison block’ and ‘a Greek army all with American accents’ (Benedict Nightingale, The Times, March 18, 1995) ‘a multi-cultural European-Asian-African chorus’ (Michael Billington, The Guardian, March 18, 1995) ‘which included Iranians and a Yugoslavian’ (Michael Coveney, The Observer, March 19, 1995), ‘whose choral odes sound Balkan, with the implication that this is Sarajevo’ (Alistair Macauley, Financial Times, March 18, 1995). Photographs relating to this production of Women of Troy (1994/5) show that the costume of the chorus with their purple/blue/gold pattern shawls and head coverings do indeed resemble a Balkan dress code. The design is also remarkably similar to the costume design of chorus of the Hecuba of 2005, including the covering of the head. www2.open.ac.uk/ClassicalStudies/GreekPlays 6 Essays No. 7, 2005 Carol Gillespie Yet, despite all the pointers to current wars and social upheaval referred to in reviews of Women of Troy the critics, whilst they did not particularly enjoy the production, did not complain about having a critique of the war in the Balkans being forced onto them, as they did with the RSC/Harrison production. Indeed John Peter notes mildly, if ironically, in his review that such correspondences in the production of Women of Troy are there to ‘tickle agreeably the consciences of the politically up-to-date’ (Sunday Times, March 26, 1995). An investigation of a close-up photograph of the Hecuba reveals that the costume of the chorus, with purples, pinks, blues and patterns of gold running through the headdress and shawls, resembles more a Slav/Balkan dress code rather than something that is exclusively Muslim. So what was it that caused the critics of the Hecuba (2005) production to, in Lorna Hardwick’s phrase, ‘islamicise the chorus’ (Hardwick, 2007)? Perhaps in part the answer lies with one aspect of the often-ignored ephemera of theatre research, the theatre programme. The programme that accompanied the London run of the RSC’s Hecuba did not contain any written references to the current situation in Iraq. There were two articles contained in the programme. The first article by Edith Hall (then the Professor of Greek Cultural History, at the University of Durham) set out a brief introduction to the cultural and social conditions of 5th century Athens which informed Euripides’ text; the second article, by Ann Shearer (a Jungian analyst) was also set in the ancient context and discussed the way in which victims can become tyrants in their turn. Nor did the programme contain any photographs relating to the production. It did, however, contain three half page photographs by Shirin Neshat, an Iranian born photographer, now living in the US. One of the photographs shows a group of women in a circular huddle apparently digging in the centre of the group as there is dust flying around The second photograph is also a group photo in a similar, possibly the same, location but with mountains more clearly visible in the background. In both photographs all the women are dressed in the traditional black Muslim chador. Only Neshat’s name as photographer, and the title of the series of photographs ‘Passage’, was supplied. Further research found that the photos reproduced in the program are stills from a moving film, which was shot, not in Iraq or Iran, but in Morocco – a more liberal Muslim country in terms of dress perhaps. Furthermore, the film was shot long before the western invasion of Iraq. Neshat herself has argued that the artist’s responsibility is neither to validate nor to critique social and political ideas and she sees her own art as a way of constructing a positive relationship to her own country of birth from the outside. (Ebrahimian, 2002). Understanding the interfaces of meaning within a photograph is also crucial. The West tends to view such representations, of women in their chador, as ‘the other’ the oppressed, the victims of a patriarchal society. Yet, Neshat’s desire is to get the West to see the positive beyond the chador, to percive the freedom and power for Muslim women that she believes lies beneath. She argues that she is an artist not an activist and therefore ‘has no agenda [and is] merely working to entice a dialogue […] . There’s the stereotype about the women – they’re all victims and submissive – and they’re not. Slowly I subvert that image by showing the most subtle and candid way how strong these women are’ (Horsburgh 2004). However, such images when taken from their original context of a moving film which tells a story, accompanied by atmospheric music, are rendered stereotypical, particularly to a western audience. And so the original meaning of Neshat’s film has indeed been left ‘up for grabs’ and changed when the RSC decided to attach the photographs to a theatre performance dealing with issues of ‘tyrant and victim, freedom and slavery, justice and expedience’ (Programme p.4). www2.open.ac.uk/ClassicalStudies/GreekPlays 7 Essays No. 7, 2005 Carol Gillespie The question remains, why were these stills from a film reproduced and used in the Hecuba theatre programme and how did they affect critical reception of the production? Did the journalists subconsciously transpose the clothes worn by the women in the programme onto that of the chorus? Is it possible their memories were more influenced by a set of photographs they could take home and study, than what they actually saw represented on the stage? Such questions are also important for discussion of the wider issue of the reception of contentious productions (see Hardwick, 2007). This brief look at images has highlighted three problematic areas that researchers need to be aware of when using photographic images as evidence: Images cannot stand alone when used as a primary source of evidence. They require detailed contextual information which should include the original conditions of the production of the photograph. Meaning in photographs is also shaped by the specific context in which they are displayed or viewed Different methods of analysis, including semiotics are required when evaluating images to enable understanding of the different layers of meaning generated. This essay has taken particular note of the role of the archivist when setting up a collection, and we intend to try and ensure that all images in our own database will be as fully contextualised as possible – or at the very least will give a history of the research undertaken in the case of each individual image! Bibliography Crimp, Douglas. 1993. "The Museum's Old, the Library's New Subject," in On the Museum's Ruins, Cambridge: MIT Press. Ebrahimian, B. 2002. 'Interview with Shirin Neshat' PAJ: A journal of performance and Art 24/3: 44-55. Hardwick, L. 2007. 'Decolonising the Mind? Controversial Productions of Greek Drama in post-colonial England, Scotland and Ireland' in C. Stray (ed.) Remaking the Classics, London: Duckworth. Horsburgh, Susan 2004. An interview with Shirin Neshat New York, Time Magazine, April, Issue 4: 44-55 [cited 20 September 2005]. Also at www.eruditiononline.come/04.04/shirin_neshat_interview.htm. Mottahedeh, N. 2003. ‘After-Images of a Revolution’ Radical History Review 86: 183-92. Rosenblaum, B. 1978. ‘Style as Social Process’ American Sociological Review, 43: 422-38. Sekula, A. 1983.. 'Reading an Archive: Photography between labour and capital’ reproduced 1999 (eds J. Evans and S. Hall) Visual Culture, Ch. 12. London: Sage Publications. Taplin, O. 1993. Comic Angels and Other Approaches to Greek Drama through Vase-Paintings, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Taplin, O.2007. Pots and Plays: Interactions between Tragedy and Greek Vase Painting of the Fourth Century BC, LA: J. Paul Getty Museum. www2.open.ac.uk/ClassicalStudies/GreekPlays 8 Essays No. 7, 2005 Carol Gillespie See most recently Taplin, 2007, for discussion of the sometimes problematic relationships between myths visual images and plays. 1 The Hecuba production (and related photographs) cited in this paper refers only to the London production in which the set design was neutral. A new set was designed for the US tour which included rows of US army tents and which more clearly corresponded to the Iraqi situation. 2 www2.open.ac.uk/ClassicalStudies/GreekPlays 9