Design Guidelines Paper - Ergonomic Society of Australia

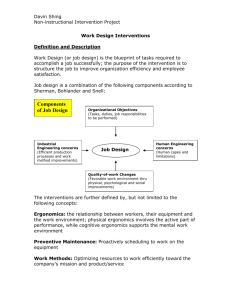

advertisement