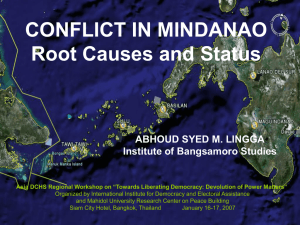

Dynamics and Directions of the Peace Negotiations Between the

advertisement