Documents about Native Americans

advertisement

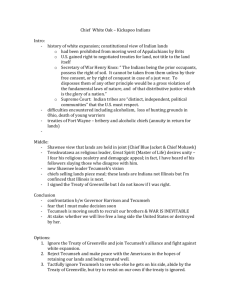

Documents about Native Americans George Washington - Message to the Senate of September 17, 1789 Regarding Treaties with Native Americans September 17, 1789. Gentlemen of the Senate. It doubtless is important that all treaties and compacts formed by the United States with other nations, whether civilized or not, should be made with caution and executed with fidelity. It is said to be the general understanding and practice of nations, as a check on the mistakes and indiscretions of ministers or commissioners, not to consider any treaty negotiated and signed by such officers as final and conclusive until ratified by the sovereign or government from whom they derive their powers. This practice has been adopted by the United States respecting their treaties with European nations, and I am inclined to think it would be advisable to observe it in the conduct of our treaties with the Indians; for though such treaties, being on their part made by their chiefs or rulers, need not be ratified by them, yet, being formed on our part by the agency of subordinate officers, it seems to be both prudent and reasonable that their acts should not be binding on the nation until approved and ratified by the Government. It strikes me that this point should be well considered and settled, so that our national proceedings in this respect may become uniform and be directed by fixed and stable principles. The treaties with certain Indian nations, which were laid before you with my message of the 25th May last, suggested two questions to my mind, viz: First, whether those treaties were to be considered as perfected and consequently as obligatory without being ratified. If not, then secondly, whether both or either, and which, of them ought to be ratified. On these questions I request your opinion and advice. You have, indeed, advised me "to execute and enjoin an observance of " the treaty with the Wyandottes, etc. You, gentlemen, doubtless intended to be clear and explicit, and yet, without further explanation, I fear I may misunderstand your meaning, for if by my executing that treaty you mean that I should make it (in a more particular and immediate manner than it now is) the act of Government, then it follows that I am to ratify it. If you mean by my executing it that I am to see that it be carried into effect and operation, then I am led to conclude either that you consider it as being perfect and obligatory in its present state, and therefore to be executed and observed, or that you consider it as to derive its completion and obligation from the silent approbation and ratification which my proclamation may be construed to imply. Although I am inclined to think that the latter is your intention, yet it certainly is best that all doubts respecting it be removed. Permit me to observe that it will be proper for me to be informed of your sentiments relative to the treaty with the Six Nations previous to the departure of the governor of the Western territory, and therefore I recommend it to your early consideration. Go WASHINTON Tecumseh, Red Cloud and Sitting Bull: Three Great Indian Leaders Diplomacy, courage and charisma were among the attributes of this trio of great Indian leaders. By J. Jay Myers Many brave and wise Indian leaders appeared and gained respect and fame in the late 18th and early 19th century. Only a few of them, however, had the diplomatic skills and charisma to go beyond leading their own bands and their own tribes to form and lead intertribal alliances. Tecumseh the Shawnee, Red Cloud the Oglala Sioux and Sitting Bull the Hunkpapa Sioux all had the right stuff to become legends. Born around 1768 somewhere near present-day Springfield, Ohio, Tecumseh developed an early hatred for the white man's steady encroachment into Indian homelands. When he was 6 years old, after invading Virginia frontiersmen killed his father, his mother took him to the spot and cried out to him: "Avenge! Avenge!" At age 12, too young to be a warrior, Tecumseh watched George Rogers Clark and some 1,000 men defeat his people and burn his town. Filled with bitterness, he swore vengeance on the Long Knives. By the early 1790s, white Americans were traveling down the Ohio River, turning north and settling on Shawnee hunting grounds. Tecumseh led raiding parties on white settlements and helped defeat two armies sent out to subdue the Indians. Officials in George Washington's administration feared a great and powerful alliance of the tribes, and the president sent Maj. Gen. Anthony Wayne out to "tame" the Indians. At the Battle of Fallen Timbers, Tecumseh was the greatest rallying force for the Indians, many times stopping retreats and inspiring them to stand and fight, but he could not prevent a crushing defeat. Nor could he prevent chiefs of other tribes from signing the Treaty of Greenville, thus ceding all of what is now the state of Ohio and part of Indiana to the whites. After that there was a period of relative peace between 1795 and 1809. But during those years, William Henry Harrison, a military man who became governor of Indiana Territory, used liquor, oratory and ceremonial pomp to persuade various chiefs to surrender 50 million acres. By 1805, Tecumseh was traveling between the Appalachians and the Mississippi persuading other tribes to join his confederacy. He told Harrison: "The Indians were once a happy race, but now are made miserable by the white people, who are never contented, but always encroaching. They have driven us from the great salt water, forced us over the mountains and would shortly push us into the lakes. But we are determined to go no farther." His oratory, of course, did not stop the white invasion, and Tecumseh decided to make use of the religious fervor being spread by his younger brother Tenskwatawa, called "the Shawnee Prophet." He planned to reform bad Indian habits, to abandon everything the white man had brought into the Indians' lives, and to try to form a huge confederacy that would include every tribe in U.S. territory. Within three years the brothers had built Prophetsville, a very large town where the Tippecanoe River flows into the Wabash, and had persuaded many chiefs that this was the last chance to stop the white encroachment. But in 1809, some Ohio Valley chiefs signed the Treaty of Fort Wayne, ceding many square miles of land. Tecumseh decided it was time for action and told Harrison he must give back the land. The governor, of course, refused. Tecumseh thought the confederacy was not quite ready for military action and withdrew. He went south to get the final agreement from a number of tribes to join the alliance. British Indian agents were encouraging an Indian uprising against the Americans. In 1811, Harrison decided to take action while Tecumseh was away, visiting the southern tribes Tecumseh had instructed Tenskwatawa not to fight Harrison, but the strong-arm governor provoked a battle at Prophetstown by moving troops to within 600 yards of the town. Insulted, the young warriors fought on November 7, 1811. Harrison's troops won the Battle of Tippecanoe, and the next day they burned the great town, center of the confederacy. The Americans had destroyed the great alliance. Read the documents and look at the map carefully, and then answer the following questions: 1. What are 3 interesting facts you discovered from the reading? 2. What are 2 questions you have about the reading? 3. What is the 1 most important thing you learned from the reading? 4. Describe the relationship between the early United States government and the Native Americans. 5. Describe the relationship between Native American tribes. 6. Why do you think there was such tension between the United States government and the Native Americans?