Running Head: RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE: A LANGUAGE ARTS UNIT

Responding to Prejudice:

A 21st Century Language Arts Unit for Middle School

Submitted to Dr. George Beckwith

By

Jane Foltz

In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the

Master of Science in Educational and Instructional Technology

National University

San Diego

9/2013

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

The Capstone Project entitled Responding to Prejudice: A 21st Century Language Arts Unit for

Middle School is approved by:

Signature_______________________________________________ Date___________

George Beckwith, Ed.D.

Capstone Faculty Advisor, School of Education

We certify that this Capstone Project by Jane Foltz entitled Responding to Prejudice: A 21st

Century Language Arts Unit for Middle School, in our opinion, is satisfactory in the scope and

quality as Masters of Science project for the degree of Master of Science in Educational and

Instructional Technology in the School of Media and Communication, at National University.

Signature_______________________________________________ Date___________

George Beckwith, Ed. D., MSEIT Lead Faculty

2

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

3

Copyright © 2013 by Jane Foltz

All Rights Reserved

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

4

Table of Contents

ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................... 5

CHAPTER 1 ................................................................................................................................... 6

Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 6

Background of the Study ............................................................................................................ 7

Statement of the Instructional/Training Problem ........................................................................ 9

Purpose...................................................................................................................................... 10

Delimitations ............................................................................................................................. 11

Definitions................................................................................................................................. 11

Summary ................................................................................................................................... 12

CHAPTER 2: Review of the Literature ........................................................................................ 13

Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 13

Historical Overview .................................................................................................................. 13

Meta-analyses of Research ....................................................................................................... 17

Instructional Elements .............................................................................................................. 19

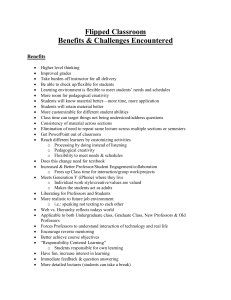

Advantages and Disadvantages of Flipped Teaching ............................................................... 21

Motivation and Effort ............................................................................................................... 22

Promoting Literacy ................................................................................................................... 24

Summary ................................................................................................................................... 25

CHAPTER 3: Project Design.................................................................................................... 26

Learning Theory........................................................................................................................ 26

Project Design ........................................................................................................................... 27

Procedure .................................................................................................................................. 27

Ethical Considerations .............................................................................................................. 32

Summary ................................................................................................................................... 33

CHAPTER 4: Project Evaluation and Discussion ........................................................................ 35

Project Evaluation ..................................................................................................................... 35

Data Presentation ...................................................................................................................... 36

Discussion ................................................................................................................................. 38

Limitations ................................................................................................................................ 40

CHAPTER 5: Summary and Conclusion ...................................................................................... 41

Conclusions ............................................................................................................................... 41

Implications for Teaching ......................................................................................................... 42

Implications for Further Research ............................................................................................ 43

REFERENCES ............................................................................................................................. 45

APPENDICES .............................................................................................................................. 50

Appendix A ............................................................................................................................... 50

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

5

ABSTRACT

Responding to Prejudice is a 21st century language arts unit designed for eighth grade middle

school students to address the essential question, "When faced with prejudice, how do people

successfully respond?" This overarching question provides a theme for reading, discussion,

watching, and listening to a variety of sources of information in print and online. As students

construct a personal response to the question, they will analyze and synthesize meaning offered

by these multiple sources and express their understanding in writing and a multimedia product.

The unit has been designed to be delivered in a flipped classroom setting; it is

hypothesized that the benefits of this model of instruction will allow for a symbiotic combination

of topic, use of online technologies, Common Core standards-based instruction, and pedagogical

approaches (specifically differentiation and gradual release of responsibility). Presently, teachers

anecdotally report that flipped teaching "humanizes" their instruction by allowing them more

time to tackle the thorny, higher levels of Bloom's taxonomy alongside their students in a

workshop-like environment. It is hoped that this particular unit will result in such humanization

while investigating an important and relevant topic that spans all of human history. (Note that

while it is intended for use with a class of students with mild to moderate disabilities, this unit

could easily be adapted for the general education population.)

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

6

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Thirteen years into the 21st century, learned members of the educational community

continue to debate characteristics of and ways to cultivate the skills and habits of mind that will

guarantee full participation in global political, social, academic, intellectual and economic life. It

is abundantly clear, however, that whatever 21st century skills are conceived to be, they are

completely and deeply intertwined with computer technology. This technology, it can be argued,

fulfills the ancient human needs "to communicate, share, collaborate, and express" (Fisher &

Frey, 2010, p. 222) on an unprecedented scale and in heretofore unimagined ways. It is also clear

that, broadly speaking, American public education has been slow to embrace and employ

computer technologies for a multitude of reasons; the rapid proliferation of technological forms

and tools may have, ironically, in and of itself slowed the pace of educational change (Flumerfelt

& Green, 2010). It is useful, therefore, for educators to heed the advice of Fisher and Frey

(2010), and "stop thinking of technology in terms of nouns (PowerPoint, YouTube, or Twitter)

and instead think in terms of verbs (presenting, sharing, and communicating)" (p. 226). In other

words, with emphasis on the affordances that technology offers in terms of "doing," the dictates

of solid pedagogy drive the educational use of technology, not the reverse.

That said, the infusion of computer technology into nearly every realm of human endeavor

necessitates a shift in not only how 21st century teachers teach but also what they teach. As

Prensky (2012) writes, "digital wisdom is a two-fold concept, referring both to wisdom arising

from the use of digital technology to access cognitive power beyond our usual capacity and to

wisdom in the use of technology to enhance our innate capabilities" (p. 202). With the pace of

knowledge growth accelerating concurrently with that of access to it, the focus in education

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

7

shifts from rote memorization with emphasis on a static set of skills to the development of

critical thinking nourished by the posing of questions, the seeking for answers, and the sharing

and expressing of what is discovered both in ourselves and the world at large (Bransford, Brown,

Cocking, 2000). The unit in question, Responding to Prejudice, blending as it does face-to-face

instruction with both asynchronous and synchronous uses of instructional technology, is rooted

firmly in this 21st century mindset. The unit's purpose is to meet multiple California Common

Core reading and writing standards (California Department of Education, 2013) while enhancing

several 21st century literacies as defined by the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE)

(NCTE, 2013).

Background of the Study

Blended instruction, as exemplified in particular by flipped classrooms, has recentely

moved quickly into mainstream teaching (Tucker, 2012). Although used by teachers for many

years in varying forms (with and without technological aspects), this teaching model has surged

in popularity due to the much-publicized work of Salmon Khan and his Kahn Academy, which

had its beginning in 2006 (Berrett, 2012). Many teachers seeking solutions to common teaching

problems are currently adopting this model in an information vacuum--with a focus on

technological tools and without a full understanding of its practical or theoretical underpinnings.

In contrast, Responding to Prejudice will be developed from a "digital wisdom" perspective,

both accessing "cognitive power beyond our usual capacity" (Prensky, 2012, p. 202) and

enhancing "our innate capabilities."

The flipped classroom model of instruction has always offered teachers several advantages.

When literature teachers assign reading for homework, as they have for many decades, they are

asking students to arrive at school prepared so that "class time can be devoted to discussions,

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

8

peer interactions, and time to assimilate and think" (Mazur, 2009, p. 51). Similarly, newer

examples of computer-based flipped instruction also require students to interact with

instructional materials in advance of class, but the materials are generally posted online in the

form of audio or video recordings. Viewed through the lens of Bloom's revised taxonomy,

students are engaging in less cognitively demanding work ("gaining knowledge and

comprehension") (Brame, n. d., para. 1) independently in or out of class, and confronting the

tougher, higher-level work ("application, analysis, synthesis, and/or evaluation") (Brame, n. d.,

para. 1) at school, in the presence of an expert teacher and peers.

Moreover, instruction that blends the use of online technologies and person-to-person

instruction enables teachers to differentiate instruction and bring to life the commonly cited four

Cs of the Common Core--collaboration, communication, critical thinking, and creativity--at the

same time. This convergence of possibilities may underlie the fervor with which teachers have

seized onto the flipped classroom phenomenon. Differentiation in the process, products,

environment, and content of learning to meet the diverse needs of students has long been touted

as the Holy Grail of instructional excellence (Tomlinson, 2001). The proposed unit, Responding

to Prejudice, purposes to harmoniously encompass differentiated instruction, the four Cs of the

Common Core, and the gradual release of responsibility model of 21st century teaching

described by Fisher and Frey (2010). With the differentiation-hallmarks of ongoing, formative

assessment; awareness of learner strengths and weaknesses; use of variously configured group

work; and emphasis on problem solving and student choice, the unit at hand will erase the

physical and temporal school/home boundaries, and open learning to a wide world of meaning

and 24/7 learning (Differentiated Instruction).

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

9

Prior to the sudden widespread interest in and use of Khan Academy videos late in the first

decade of the 21st century, the majority of teachers who had stumbled across or developed their

own versions of flipped teaching were working at the college level (Brame, n. d.; Mazur, 2009).

Thus the implementation of the flipped model in K-12 education is a relatively recent

phenomenon. Interestingly, as the impetus for adopting this model has arisen from outside

academia, research on flipped classrooms is lagging behind their establishment in American

schools.

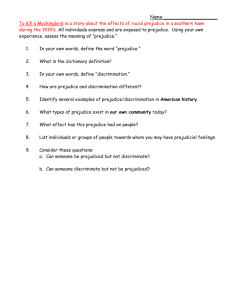

The unit, Responding to Prejudice, has been designed around the essential question,

"When faced with prejudice, how do people successfully respond?" By means of video, fiction,

and nonfiction textual sources of information, middle school resource students with mild to

moderate disabilities will be presented with real world examples of people--historic,

contemporary, and fictional--who have done just that. Students will concurrently consider the

variety of purposes that authors may have for writing and the ways in which purpose, task, and

audience give shape to meaning and message in text. Along with this content, students will

participate in a community of learners both online and at school that has first-hand experience

with the essential question. As Fisher and Frey (2006) suggest, language arts instruction for

adolescents "should be organized around big ideas" (p. 19) that matter to students. This unit

provides a relevant context for nurturing academic skills aligned with Common Core standards

while attending "to the ethical responsibilities required" for learning in a complex online

environment (NCTE, 2013).

Statement of the Instructional/Training Problem

As stated above, the language arts unit Responding to Prejudice, purposes to achieve

differentiated instruction within a gradual release of responsibility framework in a blended

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

10

learning context. Known models of instruction will thus be transplanted into a new environment

that is inconceivable without computer technology. According to the U. S. Department of

Education (2010), significant learning gains must result in order to justify the considerable time

and expense involved in developing and implementing blended learning experiences at any level.

As will be discussed, current research can only suggest which features of blended learning might

be responsible for the positive effects cautiously noted so far (U. S. Department of Education,

2010). Those elements seem to be related to "additional learning time and instructional elements"

(U. S. Department of Education, 2010, abstract) not afforded in control conditions. Benefits of

blended learning occurring in flipped classrooms do not derive, therefore, from the use of

technology per se (U. S. Department of Education, 2010). This highlights the importance of

adhering to bedrock pedagogical models of instruction in the design and implementation of this

unit, and the salience of evaluating what learners are learning as they engage in this unit, both

formatively and summatively.

The primary problem faced in designing, developing, and implementing this unit,

Responding to Prejudice, is transferring the best of known pedagogy into relatively unknown

territory, K-12 teaching. This problem is at once the greatest challenge and the greatest promise

of this unit's design.

Purpose

The purpose of this project is to provide a learning experience that blends face-to-face and

online instructional elements that will enable students to 1) meet grade-level Common Core

standards in reading and writing; 2) grow in their proficiency with technological tools and

"attend to the ethical responsibilities required by these complex environments" (NCTE, 2013,

para. 2) ; and 3) add to their "reservoir of literary and cultural knowledge, references, and

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

11

images" through "wide and deep" (California Department of Education, 2013, p. 49) reading of

fiction and nonfiction.

Delimitations

This project has been designed for a classroom that can reliably provide Internet access and

a computer for every learner each and every day. It is recognized, however, that less than 100%

of the students have computer access at home. Students will be supported as they seek access at

the after-school homework center, the early Wednesday morning hours at the computer lab, or

the public library.

Definitions

For purposes of this project, the following words are defined:

1. Flipped classroom : A form of blended learning in which the traditional pattern of classroom

instruction is inverted or "flipped on its head": content typically provided in a lecture-like format

is instead delivered out of school, while deep, deliberate practice with that content occurs at

school. For purposes of this paper, flipped learning is understood to include "regular and

systematic use of interactive technologies in the learning process" (Strayer, 2012, p. 172).

2. Gradual release of responsibility model: A model for instruction described by Pearson and

Gallagher (1983) that features a sequence of teaching that begins with explicit instructor

modeling of skills to be taught, progresses to guided practice, and ends with independent practice

or application. Responsibility for demonstrating a given skill or strategy shifts from the teacher

to the student in stages.

3. Just in Time Teaching (JiTT): A teaching strategy rooted in research done by the National

Science Foundation that refers to the process of students responding electronically to questions

that follow web-based assignments prior to class on the same topic. The teacher "reads the

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

12

student submissions 'just-in-time' to adjust the classroom lesson to suit the students' needs"

(www.ittdl.physics.iupui.edu/jitt/).

Summary

This paper will capture the unique intentions and underlying instructional design ideas that

have given shape to Responding to Prejudice, a language arts unit meant for middle school

students, in particular a class of eighth grade students with mild to moderate disabilities. This

unit will be delivered via a flipped classroom model of instruction in which students will

independently access online technology to gain background knowledge and lecture content, and

then use class time to apply and explore that content in a community of learners. Since research

on what makes flipped learning effective is scarce, the designer has been careful to rely on

known models of instruction (differentiation, gradual release of responsibility) to deliver

Common Core standards-based instruction. It is hypothesized that the flipped approach will in

fact make the aforementioned models easier to implement. The result, it is hoped, will be an

engaging unit that will promote the four Cs shared by most lists of 21st century skills and the

Common Core standards: collaboration, communication, critical thinking, and creativity.

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

13

CHAPTER 2: Review of the Literature

Introduction

The purpose of this project is to create a flipped classroom unit of language arts instruction

for middle schoolers that will ignite student interest and engagement while enabling them to

meet grade-level Common Core standards in reading and writing. This will occur within a

relevant and timely context for learning framed by the essential question, "When faced with

prejudice, how do people successfully respond?" Student learning will be measured by both

formative and summative assessment (the latter in the form of two performance products: an

essay and a multimedia project.) This project reflects the contemporary view that the lecture

"model is making less and less sense as sources of information grow more plentiful" (Berrett,

2012, para. 30). Supporting research and information on the flipped model of instruction and its

constituent, instructional supports is found in journal and book sources by means of the search

terms "flipped classroom," "instructional technology," and "21st century skills." This chapter will

present a brief history of the flipped classroom model, the theoretical framework that undergirds

it, and research that points to important components of the unit design.

Historical Overview

For decades, college humanities professors, among others, have engaged in flipped

teaching in a basic form but powerful form (Berrett, 2012). Independent reading has been

assigned for homework, while class time was reserved for in depth discussions of plot, literary

device, meaning, and so on (Berrett, 2012). In the sciences, flipping has been adopted in niches

(Berrett, 2012). In the mid-1990's, for example, the math department at the University of

Michigan began to flip calculus courses; students would complete reading prior to class and

engage in problem-solving in class at the board or in groups with professor support (Berrett,

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

14

2012). As one lecturer observes, students are "learning how to think," and teachers are "learning

what they're struggling with" in the classroom (Berrett, 2012, para. 21). According to pre- and

post-test measures of student learning, University of Michigan students in flipped "courses

showed gains at about twice the rate of those in traditional lectures at other institutions who took

the same inventories" (as cited in Berrett, 2012, para. 24).

Mazur, a physics professor at Harvard University, "has been flipping his courses for 21

years using an evolving method he calls 'peer instruction'" (PI) (Berrett, 2012, para. 28). Mazur

(2009) has developed PI in response to mounting evidence of student difficulty applying

concepts taught to novel situations after receiving information in the traditional lecture-read-test

sequence of transferring content. Mazur (2009) began to require that students read new material

in advance of class; "this initial information transfer through reading allows the lectures to focus

on the most important and difficult elements...perhaps from a different perspective or with new

examples" (Crouch & Mazur, 2001, p. 973).

The PI twist has class beginning with students answering a few "short, conceptual

multiple-choice questions" (Mazur, 2009, p. 51) based on homework. As students respond via

hand-held "clickers," the professor can immediately view the level of understanding in the class.

"If between 35% and 70% of the students answer" (Mazur, 2009, p. 51) correctly, they are

prompted to search for a peer with a different answer; Mazur and teaching assistants circulate

and coach as learners "apply the core concepts" and "try to convince each other of the

correctness of their own answer by explaining the underlying reasoning" (Crouch & Mazur,

2001, p. 970). Students then re-answer the questions, and the professor can calibrate the next

instructional steps to student need demonstrated in the moment. Crouch and Mazur (2001)

suggest that this sequence represents an adaptation of JiTT.

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

15

Interestingly, Mazur also addresses the issue of student motivation in his PI model, which

also must be tackled in Responding to Prejudice. This author requires that students answer three

free response questions on the assigned reading before each class, online. The third question, he

reports, is always, "'What did you find difficult or confusing about the reading? If nothing was

difficult or confusing, tell us what you found most interesting" (Crouch & Mazur, 2001, p. 973).

Students earn effort-based credit for their responses, which help guide the teaching that

immediately follows. This professor employs two forms of motivation: basing grades "on

conceptual understanding, not just traditional problem solving" (Crouch & Mazur, 2001, p. 974)

and "setting the right tone in class (including explaining the reasons for teaching this way)". The

core principles of Mazur's PI model--information transferred ahead of instruction, formative

assessment of initial understanding, in-class application of new information to new contexts, peer

discussion ingrained in the resolution of conceptual misunderstandings, and constant teacher

calibration to student need--represent the key features of any flipped instructional setting. These

in turn recommend the model to nearly any teaching context. Remarkably, these principles are

quite similar the hallmark characteristics of instructional differentiation noted in Chapter 1:

ongoing, formative assessment; awareness of learner strengths and weaknesses; use of variously

configured group work; and emphasis on problem solving (Robb, 2008).

Notably, Mazur suggests that similar classroom situations can be conjured without

"clickers" or any form of technology; he has, however, developed an improved "clicker" that can

pinpoint students who need assistance according to seat number so as to arrange small groups to

best advantage (Mazur, 2009). For this author, however, "it is not the technology but the

pedagogy that matters" (Mazur, 2009, p. 51). Mazur (2009) reports "that learning gains nearly

triple" (p. 51) when "students are given the opportunity to resolve misunderstandings about

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

16

concepts and work together to learn new ideas and skills." As Prensky (2011) writes, "changes

toward the way today's kids learn best must drive the technology we acquire and use, rather than

having our future classrooms be driven by any technology's feature set, bandwidth, availability,

or price" (Prensky, 2011, para. 19). Thus technology can contribute to PI or any form of flipped

teaching in a variety of forms workable for any subject, activity, audience, and teacher.

A quantitative study by Deslauriers, Schlew, and Wieman (2011) explores the

effectiveness of two differing instructional approaches in large-enrollment (more than 200student), university physics classes: three hours of traditional lecture versus three hours of

instruction featuring elements of flipped instruction. The treatment condition involved "moving

the simple transfer of factual knowledge outside of class...and creating tasks and feedback that

motivate students to become fully engaged" in class (Deslauriers, Schlew, & Wieman, 2011, p.

862). In-class activities included student "deliberate practice in 'thinking scientifically'"

(Deslauriers et al., p. 862) along with pre-class reading, pre-class quizzes on readings, "in-class

clicker questions" (Deslauriers et al., p. 863), student discussion, group problem solving, and inthe-moment teacher feedback. Learner attendance, engagement, and quantity learned all

measured significantly higher in the treatment group which included students, learning

objectives, instructional time and exams similar to the control group.

A Wagner, Laforge, and Cripps (2013) qualitative report examines the effects of a flipped

lecture component in engineering courses at the University of Regina. A given percentage of

lectures in a given course were simply delivered by supplying video lectures, supporting online

materials, and in-class assignments prior to class. Survey feedback provided by both instructors

and students suggests that the flipped model was a resounding success. Specific conclusions

drawn by Wagner et al. (2013) include the following: 1) "success of flipped lectures is directly"

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

17

(p. 4) related to the in-class assignment, with individual work following group interaction

seeming to provide the greatest educational benefit; 2) 10 to 15 minutes of video was preferred

by students; 3) videos were viewed repeatedly by students; 4) student opinion held that one

flipped lecture per week (30% of lecture time) was optimal; 5) video production consumed 2 to 3

hours of instructor time per 15-minute lecture; and 6) instructors gained back several hours by

providing review materials online prior to tests. In sum, study results generated enthusiasm

among faculty; the key to success in lecture-flipping, according to Wagner et al. (2013) is

student use of class time to "work on a strategically designed instructor-supported assignment"

(p. 2).

Meta-analyses of Research

The U. S. Department of Education Evaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online

Learning: A Meta-analysis and Review of Online Learning Studies (2010) provides the

remarkable conclusion that "no experimental or controlled quasi-experimental studies [from

1994 through 2006] that both compared the learning effectiveness of online and face-to-face

instruction for K-12 students and provided sufficient data for inclusion in a meta-analysis" (p.

xii) could be found. However meta-analysis of 50 study effects, most of which involved older

learners, yields the following key finding: "students in online conditions performed modestly

better, on average, than those learning the same material through traditional face-to-face

instruction" (U. S. Department of Education, 2010, p. xiv). Further, instruction that blended

online and face-to-face instruction resulted in greater measurable benefits than pure online

instruction when compared to pure face-to-face contexts (U. S. Department of Education, 2010).

The only other instructional variable found to produce statistically significant benefits was

collaborative or instructor-mediated (versus purely independent) online activities. Narrative

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

18

review of what studies were available suggests the following conclusions: 1) blended and soleonline instruction within single studies produce similar learning outcomes; 2) learning outcomes

in online settings cannot be attributed to any specific media elements such as online quizzes or

video; and 3) online courses that include opportunities for reflection and "self-monitoring of

understanding" (U. S. Department of Education, 2010, p. xvi.) enhance learning. The findings of

this meta-analysis support the notion that what makes flipped teaching effective is not the

inclusion of technology per se, but rather the provision of meaningful online instruction followed

by student-centered learning activities that might not otherwise occur.

Bishop and Verleger (2013) provide The Flipped Classroom: A Survey of the Research

which highlights the reality that flipped classroom instruction success depends on the in-class

instruction, not just the provision of video lecture (as was suggested by Wagner et al., 2013).

Although they encounter the same paucity of thorough and comparable research as did the

U. S. Department of Education (2010), they posit a few key findings: 1) student reaction to

flipped learning is generally positive; 2) college students come to class better prepared when

supplied with video lectures versus textbook reading; and 3) pre-class online quizzes on videolecture content are appreciated--and even requested--by college students (Bishop & Verleger,

2013).

Usefully, Bishop and Verleger (2013) include a discussion of the theoretical framework

supporting the flipped classroom model as they characterize it--pre-recorded lectures assigned

for homework with class time reserved for interactive learning activities "that cannot be

automated or computerized" (para. 10). Flipped instruction, they caution, is not the mere reordering of homework and class work; without in-class activities shaped by "student-centered

learning theories" (Bishop & Verleger, 2013, para. 27) after Piaget and Vygotsky, "the flipped

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

19

classroom," they assert, "simply does not exist." Flipped classroom activities may take the form

of problem-based learning, peer tutoring, collaborative learning, cooperative learning, or peerassisted learning (Bishop & Verleger, 2013). All of these iterations of student-centered learning

fall into the overarching category of active learning according to these authors. Prince (2004)

defines active learning as "any instructional method that engages students in the learning

process" (as cited in Bishop & Verleger, 2013). The flipped classroom, Bishop and Verleger

(2013) conclude, in fact unites the best of two seemingly incompatible learning theories-constructivism in the form of active, student-centered learning in a social context and

behaviorism in the form of direct instruction.

Instructional Elements

The use of either teacher-created or other videos is also supported by learning theory.

According to Bonk's (2008) discussion of research from the 1990's, online videos construct a

"macrocontext," or shared contextual experience, to ground instruction in a community of

learners. The fact that videos are always available and easily reviewed strengthens their ability to

provide a common learning space in which to anchor instruction and/or build prior knowledge.

Bonk (2008) also suggests that video-viewing resonates with dual coding theory in that

information can be recalled "through both verbal and visual channels" (para. 19). This may in

turn enhance memory of content since several types (semantic and episodic) can be activated at

once (Bonk, 2008). The chunking of content necessitated by the creation of short videos is also

recommended by growing understanding of brain function, as is the importance of repetition of

important content (Medina, 2008).

The "brain rules" for memory elucidated by Medina (2008) in his book of same name seem

to support many of the facets of flipped instruction reviewed thus far. For example, information

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

20

that is endowed with a higher "quality of encoding" is more easily remembered and retrieved

(Medina, 2008). "'Quality of encoding' really means the number of door handles we can put on

the entrance to a piece of information...The handles we can add revolve around content, timing,

and environment" (Medina, 2008, p. 144). All of those "handles" are easily controlled by the

teacher in flipped learning contexts, with timing being partially under the control of students who

can watch and re-watch video lectures as they wish. Similarly, Medina (2008) concludes that

"the best way to make long-term memory more reliable is to incorporate new information

gradually and repeat it in timed intervals" (p. 147). Again, this level of fine-tuning of information

presentation dovetails nicely with and if afforded by the flipped model of instruction.

Robert and Dennis (2005) present interesting findings on the impact of instructional media

that is rich in social presence versus media that is "lean" and lower in social presence. Contrary

to other studies, the authors found that media high in social presence [such as synchronous chats]

"induces increased motivation but decreased ability to process, while...media low in social

presence [such as asynchronous wikis and discussion boards] induces decreased motivation but

increased ability to process" (Robert & Dennis, 2005, p. 19). The implications are that media

used for online instruction should be carefully chosen with an eye to the learning objectives to be

accomplished. "What is vital" when designing online instructional materials is "not always the

sense of presence...but having sufficient information in the appropriate format and the ability to

duly consider it" (Robert and Dennis, 2005, p. 19).

It would seem to follow that uses of asynchronous and synchronous elements in online

instruction should be carefully chosen and balanced with respect to each other. As Hrastinski

(2008) forwards, "the e-learning community needs an understanding of when, why, and how to

use different types of e-learning" (p. 2). A small study conducted by Hrastinski analyzed

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

21

sentences contributed by learners in both synchronous and asynchronous online discussions.

After sorting the sentences into three categories--content-related, task-planning-related, socialsupport-seeking or -giving-- Hrastinski (2008) concludes that the two forms of online discussion

serve different purposes; "synchronous e-learning better supports personal participation and

asynchronous e-learning better supports cognitive participation" (p. 4). Ultimately, it seems, the

two complement each other, and it falls to the instructional designer to match form to function.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Flipped Teaching

Given the current "buzz" being generated by the flipped classroom topic in educational

circles, the informal, professional literature is full of teacher anecdotes and implementation

advice. A compilation of the benefits of flipped teachings cited in various sources is as follows:

1) efficiency of information transmission via video; 2) reusability of videos improves teacher

quality of life; 3) strengthened relationships with students via more class time for productive

interactions and the "taking of the teacher home" in 24/7 video form; 4) enhanced teacher

reflection on their own teaching; 5) increased class time for student collaboration; 6) vastly

improved opportunities to differentiate instruction by student; 7) chance to customize

curriculum; 8) easy teacher sharing of multimedia resources; 9) increased student engagement

and learning; and 10) flexibility that resonates with this generation of students. (Brunsell &

Horejsi, 2013; Fulton, 2012).

An additional benefit of flipped teaching is the opportunity to provide immediate teacher

feedback on student work, as has been discussed. In the case of Responding to Prejudice in

which writing is a major focus of instruction, the chance to provide feedback to students on an

individual basis as they traverse the writing process is a huge boon (Berne, 2010). As

Warschauer (2010) observes, approximately two decades ago, it was feared that the growing

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

22

hegemony of Internet multimedia would erode the importance of writing. Today, not only have

these fears not been realized, but, according to the National Commission on Writing (2003)

"writing is more important than ever before" (as cited in Warschauer, 2010, p. 3). Blogs and

wikis (and the threaded discussions they enable) allow for "exploring identity, expressing one's

voice, airing diverse views, and developing community" (Warschauer, 2010, p. 4). Further, wikis

and online collaborative writing platforms such as Google docs allow for same-time group work

and preserve a history of student contributions and edits for the teacher (Warschauer, 2010).

Additionally, Warschauer states that studies of collaborative online writing with second language

learners point to increased writing quantity and writer confidence online (Warschauer, 2010).

In and amongst the many benefits that flow from flipped classroom teaching, there are

drawbacks recorded in the literature. Several studies report initial student dislike of the model, in

particular its emphasis on the work to be done accountably, in advance of class (Herreid &

Schiller, 2013; Berrett, 2012; Crouch & Mazur, 2001). Crouch and Mazur (2001) warn teachers

to expect a period of adjustment to the new model that might be accompanied by a brief decline

in performance. "With significant effort invested to motivate students, student reactions to PI are

generally positive," in time (Crouch & Mazur, 2001).

Motivation and Effort

Given the student audience for which Responding to Prejudice has been designed (a very

diverse group of special eduation students), motivation is an issue that must be thoughtfully

addressed. In accordance with Mazur (2009), there will be multiple mechanisms for recognizing

student effort in contrast to performance. As Wiest, Wong, Cervantes, Craik and Kreil (2001)

discuss in a study of regular and special education high school students on measures of

"perceived competence" and "academic coping" (abstract), "positive information from significant

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

23

others fosters the development of competence, which in turn impacts academic success" (p. 113).

Their findings suggest that students with learning disabilities demonstrate "less academic

competence than do matched students with the same cognitive abilities" (Wiest et al., 2001, p.

114). Further, such students tend to "attribute their failure to their lack of ability," which is a

hallmark characteristic of a fixed mindset. (Terrell, 1990 as cited in Wiest et al., 2001, p. 115).

This conclusion speaks to the importance of cultivating a growth mindset in students. As

explained by Blackwell, Trzesniewski, and Dweck (2007), "children's beliefs become the mental

'baggage' that they bring to the achievement situation" (p. 259). These authors conclude that a

focus on student potential for growth and development of intellectual capacity, no matter the rate

of development, according to a growth mindset, "provides a host of motivational benefits"

(Blackwell et al., 2007, p. 260). A study by Schunk and Cox (1986) renders the surprising

discovery that simple recognition of student effort as reflected in the spoken words, "'You've

been working hard,'" produced significant gains in both self-efficacy and skill development in

students with learning disabilities (p. 204). All of these findings hint at strategies to weave into

the unit, Responding to Prejudice.

Historically, this group of students has struggled with sustaining focus, motivation,

and effort across tasks that require any length of time. The students' willingness to commit to a

blended learning environment is a potential problem that will be addressed by elements of the

instructional design in ways large and small, from chunking of tasks, to presenting captivating

visual sources of information, to tangibly recording student progress. Specifically, creating

"effort-to-progress graphs" for distinct learning tasks will "mimic the incremental progress

feedback provided by getting to the next level on a computer game" (Willis, 2011, para. 14). As

a result, it is anticipated that students will "experience the dopamine-pleasure response and

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

24

intrinsic motivation of meeting a challenge" (Willis, 2011, para. 10). This encourages the brain

to work toward another such experience and carry effort into the next task (Willis, 2011). Also,

graphing individual growth and effort supports differentiation by recognizing that each student

presents a different profile of strengths and weaknesses, and will travel a different trajectory of

learning. Students will also receive visual feedback for working hard by means of the awarding

of points on Class Dojo (classdojo.com, 2013).

Promoting Literacy

It should be noted that the design of this unit, from its largest outline of activities that

sequentially build to the development of "big ideas" to the smallest discrete chunk of vocabulary

instruction, has been informed by the current understanding of developing literacy in

adolescents. Recognizing the fact that "conflicting messages about literacy practices" that will

support implementation of the CCSS in language arts are currently being communicated by

policy and product, the International Reading Association (IRA) (2012) has published a CCSS

implementation guide. This article offers several salient suggestions for teachers planning

language arts instruction in the here and now. Specifically, the IRA advises that "an ambitious

itinerary of rich and varied narrative and informational texts, including some texts that are

easier" (International Reading Association, 2012, p. 1) as well as texts that require students to

stretch their current ability be accessed. Further, the IRA suggests that the "close, attentive"

reading demanded by the CCSS should proceed to the next step of "using the information and

ideas drawn from text...as the basis of one's own arguments, presentations and claims"

(International Reading Association, 2012, p. 2). Reading and writing are, of course, mutually

reinforcing, and the CCSS requires teaching that encourages their concomitant growth and

support. This source recommends the purpose and format of the forthcoming unit. Additionally,

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

25

the IRA (2012) states that student presentation of ideas "in writing and multimedia formats are

central to the Standards [sic], and as such, students need to know how to summarize text,

critically analyze the information presented in texts, and synthesize information from multiple

texts" (p. 3). All of these skills are embedded in the unit at hand.

Summary

Even in the absence of definitive scientific studies comparing the efficacy of face-to-face

to flipped classroom instruction for K-12 students, a growing body of research offers several

conclusions as to benefits and elements that promote its success. One prominent conclusion

centers on the role of technology. First and foremost, this model is best understood as a way to

improve pedagogy by solving instructional dilemmas; carefully chosen technological elements

are enabling parts of a solution, not solutions in and of themselves. "The regular and systematic

use of interactive technologies" (Strayer, 2012, p. 172) does characterized flipped or inverted

teaching in most studies, however. Together, these ideas suggest the importance of careful

matching of technological tool to instructional intention.

Chief benefits include increased time available for deeper, active learning inside the

classroom, documented learning gains, and enhanced opportunities to differentiate instruction.

Flipping success can be boosted by including web-based student accountability measures for outof-class work a la JiTT, recognizing student effort, and providing conceptual coherence between

what happens out of class and what happens in class (Couch & Mazur, 2001; Mazur, 2009;

Strayer, 2012). Perhaps most importantly, research suggests that carefully flipped learning does

allow teachers to achieve what might be an overarching goal for most: a more connected, more

stable, more dynamic, and more personalized classroom learning experience (Strayer, 2012).

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

26

CHAPTER 3: Project Design

Learning Theory

Responding to Prejudice, which has been designed to be delivered according to flipped

teaching principles, relies on several learning theories. Very simply put, behaviorism holds that

an instructional stimulus will trigger a learning response (Harasim, 2012). Next, cognitivism

suggests that between stimulus and response something occurs which is worthy of educator

attention (Harasim, 2012). That something is the activation of and building upon schemata

(Harasim, 2012). Under cognitivism per Gagne, it is imperative that instruction follow nine

steps: 1) hooking attention, 2) stating the learning objective, 3) activating prior knowledge, 4)

providing new information, 5) guiding learning so as to enhance long-term memory, 6) students

demonstrate understanding, 7) providing feedback on step six, 8) formal assessment, and 9)

promoting memory and transfer of what has been learned (Harasim, 2012). Next, in contrast to

behaviorism and cognitivism, constructivism most significantly shifts emphasis to the role of the

learner who constructs "their own understanding and knowledge of the world" (Harasim, 2012,

p. 60) through personal experience and reflection. This very simplified summary of the major

schools of learning theory shows that, from school to school, progressively greater and greater

emphasis is placed upon the active learning intentions of the student as the key to successful

instruction. The understanding that students must travel through a continuing process of

disequilibration and requilibration to gain new learning (cognitive structures) is an important

tenet of constructivism (Harasim, 2012). The instructor's role changes as well, from purveyor of

information to coach and conjurer of the active learning environment.

The instructional unit at hand most predominately features cognitivist and constructivist

learning theory elements, although it must be stated that the boundary between these two schools

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

27

is at times indistinct. Gagne's nine steps all appear in flipped teaching as described in this paper,

if not always in one linear sequence; and flipped teaching emphasis on active student

construction of knowledge through deliberate practice in a social learning context comprised of

teacher and peers, face-to-face and online, is decidedly constructivist.

Project Design

This unit has been designed in backwards fashion per McTighe and Wiggins (2004) to

address an overarching essential question, "When faced with prejudice, how do people

successfully respond?" The "end" learning objectives are grade-level Common Core standards in

reading and writing, and the assessment products have been designed to demonstrate the meeting

of those objectives along with student construction of an answer to the essential question.

This design process harmonizes with the oft-cited ADDIE (analysis-design-developmentimplementation-evaluation) model. Student needs have been analyzed, a meaningful context and

appropriate learning objectives for learning identified, and a sequence of learning activities

designed and developed. The unit will be implemented with students in the coming 2013-2014

school year. Evaluation of the design is ongoing with feedback from subject matter experts

(SMEs) and usability testers, and final evaluation of the unit itself will take place at the

conclusion of the implementation phase. Final evaluation data will be provided as results of a

student survey, two performance products, and designer/instructor reflection.

Procedure

This unit has been designed for a diverse group of 18 8th grade students at a public middle

school in San Jose, California. This group is comprised of special education students with mild

to moderate disabilities including autism, specific learning disability, emotional disturbance, and

Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD) (see Table 1). Approximately one fifth of these

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

28

students are also English language learners (ELLs). All but one are reading a year or two years

below grade level. By virtue of their life circumstances, many of these students have first-hand

experience with prejudice.

Target User Characteristics

middle school students

many are avid video game players

80% read below grade level

75% male

50% have specific learning disabilities

45% have Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder

20% English language learners

10% have autism

5% carry the designation "emotionally disturbed"

~90% have routine computer access at home

Comments

only basic academic experience with technology (word

processing, PowerPoint)

used to conventions of this medium

simple, clear, brief language needed

require chunking of content and tasks,

and specific, frequent feedback

require clarity of task and purpose delivered with brevity

plus chunking of

content and tasks

require clarity of language in their ZPD for academic

vocabulary

display a low frustration threshold

group work needs to be carefully structured

display a low frustration threshold

group work needs to be carefully structured

display various levels of comfort with technology

generally

Table 1. Characteristics of the target audience for Responding to Prejudice.

Learning goals are as follows: 8th grade language arts student skills and understanding will

grow in specific ways described below.

1. Students will understand that writing is shaped by author's task, specific purpose, and audience

when the same theme is explored in different ways.

2. Students will learn to recognize the elements of writing that vary according to author's chosen,

specific purpose and audience.

3. Students will add to their "reservoir of literary and cultural knowledge, references, and

images" through "wide and deep" (California Department of Education, 2013, p. 49), careful

reading of fiction and nonfiction.

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

29

4. Students will grow in their proficiency with technological tools and "attend to the ethical

responsibilities required by these complex environments" (NCTE, 2013, para. 2).

Common Core standards-based learning objectives identified at the outset of the design

process are as follows below.

1. After reading a grade 6-8 level text, eighth grade resource language arts students will be able

to identify the author's task and purpose [as "express and reflect," "inform and explain",

"evaluate and judge," "inquire and expore," "analyze and interpret", or "take a stand/propose a

solution" (Gallagher, 2011)], and justify their identification in a paragraph that cites at least three

supporting pieces of evidence from the text and that scores a 3 or higher on a 4 point rubric.

CCSS.ELA.RI.8.6. (California State Department of Education, 2013).

2. After reading two or more texts on the same topic or theme, students will be able to analyze

how differences in text structure, tone, and word choice contribute to the authors' purposes and

the meanings delivered as evidenced by completion of a compare/contrast mindmap and

accompanying essay that scores at least 3 on a 4 point rubric. CCSS.ELA.RL.8.5. (California

State Department of Education, 2013).

3. As the unit concludes, students will write an essay that demonstrates a self-selected purpose

(choices listed under item 1) and conveys what they have learned in answer to the unit's essential

question using a minimum of two, correctly cited and integrated sources that scores at least a 3

on a 4 point rubric. CCSS.ELA.W.8.2. (California State Department of Education, 2013).

4. Students will use Google docs to compose written pieces to be edited by teacher and peers;

students will provide thoughtful editing advice for at least one peer using Google docs with a

focus on how effectively purpose and audience have been considered. Student comments and

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

30

advice will score at least a 3 on a 4 point rubric. CCSS. CCR.W.6-12.4-6. (California State

Department of Education, 2013).

5. Students will create and then present a multimedia presentation (from a menu of choices) that

expresses the main ideas presented in their essay (see item 3) that scores at least a 3 on a 4 point

rubric.

6. Students will complete all online and in-class assignments and reading as evidenced by an

average of 80% or higher on all scored checks for understanding to be calculated one third, two

thirds, and three thirds of the way through the unit.

7. Students will adhere to the class-created code of online conduct as measured by teacher and

self checklist ratings.

With audience analyzed and learning objectives defined, this unit was designed to follow

the flipped classroom model. Specifically, out-of-class activities will be comprised of presenting

and briefly responding to new information which will provide (or activate) prior knowledge.

These activities will be housed on a website, www.msfoltz.weebly.com. Prior-to-class

instruction will take the form of teacher-created or -selected multimedia, image, or text sources

of information. Online checks for understanding are easily provided by Google forms; the results

of which can be quickly viewed by the teacher before class in accordance with JiTT. Each

student has their own Google drive account which will permit opportunities for real-time teacher

and peer editing of work, collaborative writing activities, and organization of learning resources.

In-class time will then be used to address student gaps in knowledge or misunderstanding

revealed by results of online checks for understanding according to PI principles. Moreover,

class time will be freed up for creation of high-cognitive-demand writer's workshop activities

punctuated by many opportunities for one-to-one writing instruction. Weekly socratic seminars

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

31

in which the essential question is revisited in light of new thinking can also reliably fit into the

sequence of instruction, as will close-readings of more challenging text passages. In short, the

flexibility of the flipped classroom model will permit the teacher to responsively use JiTT

strategies--and hopefully gain significant instructional traction with this group of students with

special needs.

Technology will enhance this unit in several important ways. First, it is hoped that the

documented benefits of forms of social media will extend to this opportunity to develop 21st

century communication skills. Specifically, students developing these skills can "write for a

social audience and hone their words in response to others, while becoming sensitive to both the

benefits and risks of expressing themselves online" (Warschauer, 2010, p. 4). A wikipage will

house an asynchronous discussion board for the class novel to be read as part of this unit. The

very recent novel, Wonder, by R. J. Palacio (2012) will provide a common thread for theme and

reading response. The reading level of this novel aligns with the independent reading level of the

majority of students in class. Further, the website www.todaysmeet.com will enable a

synchronous role play of students as Wonder characters. These uses of social media adhere to

suggestions from the literature, with a high-thinking activity occuring in the asynchronous form,

and a high-participation activity occuring in the synchronous form. Finally, each student will

create a rubric-scored multimedia performance product and an essay to culminate this unit.

Scores will suggest the degree to which students have learned what was intended to be taught

and developed answers to the essential question. Students will ultilize the multimedia format that

they prefer.

In accordance with GRR framework, reading and writing tasks will be progressively less

and less scaffolded as student progress allows. Students will apply what they have learned,

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

32

especially in terms of writing, with greater and greater assimilation of understanding of text form

and author purpose. Careful construction of a conceptual understanding of the essential question

undergirds the progressive transfer of responsibility to students. The web-based padlet.com

canvas on the ladder of prejudice that is created by the efforts of all is one example. A literal

framework (ladder) acts as a thinking map to organize events and ideas in conceptual categories.

This incorporates a kinesthetic element as well, since events/ideas recorded on "stickies" can be

repositioned via mouse.

As suggested by the review of literature, careful selection of out-of-class sources of

information must be complemented by in-class learning activities that are just as carefully

planned to ensure successful implemenation of this unit. Essentially all of the learning activities

that comprise this unit are resonant with Guidelines for ELA Instructional Materials

Development (Bunch, 2012). Some of these guidelines, developed for English language learners

but completely appropriate for any population of learners are as follows: 1) "begin with a potent

set of Common Core" standards (Bunch, 2012, p. 3); 2) design lessons to allow students with

interact with standards recursively; 3) provide various instructional pathways to encourage high

levels of access to all students; 4) choose fiction and non-fiction texts of various levels of

complexity; 5) focus on different aspects of complexity at different times; 6) provide chances for

activation and building of prior knowledge to allow text access; 7) give students chances to write

with different purposes; and 8) "utilize different participation structures" (Bunch, 2012, p. 3). A

brief glance at Responding to Prejudice demonstrates that all of these instructional design

guidelines have been followed in its creation.

Ethical Considerations

Actual use of this instructional unit poses potential ethical concerns in the areas of online

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

33

privacy, exposure to unintended web content, and inappropriate online student-to-student

communication. Most of these are obviated by the chosen tools themselves. The wikipage to be

used for the Wonder discussion board, for example, offers page-level security. Student work on

Google docs is similarly private according to "sharing" settings. Embedding YouTube videos on

the website, www.msfoltz.weebly.com, precludes the possibility of students viewing other

YouTube videos at the same time and location. The final concern will be addressed by student

creation of an online code of conduct for student-to-student communication; consequences for

failure to adhere to the code will be chosen and agreed to by students. All of the technological

tools employed in this unit (with the exception of padlet) preserve a thorough edit history for the

teacher to peruse should the need arise.

Alpha testing of this unit is being performed by the instructor, one SME, and the

instructor's family. No ethical concerns will arise from alpha testing.

Summary

In sum, Responding to Prejudice has been designed according to the ADDIE model and

the backwards design framework. Both the content and sequence of learning activities thus began

with their end--demonstrated attainment of Common Core standards-based goals and a greater

understanding of the issue of prejudice--in mind. Technology-based resources presented at

www.msfoltz.weebly.com run throughout the unit, allowing a flipped classroom approach to

highly signficant academic content. The end result hopes to be a captivating out-of-class element

synergistically combined with in-class work characterized by deep, deliberate practice of skills

and development of critical thinking. Seen through a constructivist lens, this unit will encourage

students to construct new understandings of the purposes of different forms of writing, several

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

instances of prejudice in their shared cultural heritage, and of ways in which people have not

only survived hardship but responded to it in dignified and successful ways.

34

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

35

CHAPTER 4: Project Evaluation and Discussion

The online portions of Responding to Prejudice, which comprise the heart of this project,

have undergone usability testing prior to implementation with students, which will occur outside

the realm of this capstone paper. Formative assessment measures run through the unit thanks to

JiTT and more, and two authentic, summative assessments will be administered at unit

completion. Apart from usability and academic measures, student effort, engagement, and

enthusiasm for flipped learning will also be assessed as they were addressed by the designer as

important dimensions affecting the learning process. Thus the various instances of assessment

will touch on all four of Kirkpatrick's Four Levels: reaction, learning, behavior (application of

learning), and results (Kirkpatrick & Kirkpatrick, 2009).

Project Evaluation

In this case, the end result of the instructional design process aspires to be a streamlined,

nearly seamless, and almost effortless web experience that synergistically complements the

content for students (not just the designer) it only makes sense to be sure that this has been

achieved. Ever-mindful of the possible perspectives of future users, a careful designer welcomes

a usability evaluation to witness those perspectives in action. Usability testing, writes

Mehlenbacher (1993), provides designers with information about design shortcomings that can in

turn point to "possible solutions to those shortcomings" (p. 211).

Usability is usefully broken into five defining facets, the "5Es" delineated by Quesenbery

(2001). A usable web interface is "efficient, effective, engaging, error tolerant, and easy to

learn" (Quesenbery, 2001, para. 6) . Efficiency has do with how quickly and how accurately a

given task can be accomplished, whereas effectiveness has to do with the extent to which user

goals are achieved as intended (Quesenbery, 2001). An engaging interface is easy to read, not

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

36

just in terms of accessible text features, but also in terms of the flow of content in a sensible and

non-frustrating presentation (Quesenbery, 2001; Williams & Tollett, 2006.) In this particular

case, error-tolerance will be characterized by navigation that aspires to follow common

expectations and therefore makes errors unlikely. This web interface can be called "easy to

learn" if students with differing levels of experience with computer technology are able to

accomplish all that will be required with a very minimal level of frustration and a negligible

learning curve.

After implementation, the unit will be evaluated by student survey (see Appendix A) found

on the final page at www.msfoltz.weebly.com, and by the scores earned by students on the two

performance products that will wrap up the unit. The learning objectives that initiated and shaped

the unit design set rubric-score goals for three pieces of writing (paragraph on author's purpose in

a given piece, a compare/contrast piece, and the final essay) and the multimedia project. Student

learning of content, work completion, and engagement will also be measured, with a goal of an

ongoing average of 80% or higher on online quizzes and graded checks for understanding plus a

goal of 80% of assignments completed. With support to boost and maintain student motivation

purposefully built in to the unit, effort measures provided by xp progress graphs and Class DOJO

will be provide important metrics of the student experience. Student adherence to the online code

of conduct will also be measured, primarily for student benefit, by teacher and self-rating

checklists at the appropriate time.

Data Presentation

Five users took part in usability testing of the website that houses the unit, Responding to

Literature. Four completed two given tasks and completed a survey immediately thereafter; they

ranged in age from 16 to 54, and in computer-familiarity from beginner to expert. One SME

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

37

completed the same tasks in front of the designer and "talked aloud" as they did so. A great deal

of valuable, actionable information was gained from both processes.

Post-Use Survey Questions on the the 5Es

1. I was able to go this fast AND accomplish my given tasks.

2. I took about this many wrong turns getting my tasks done.

3. I was able to find the "Wonder" discussion board...

4. I found the multimedia presentation on the purposes of

writing _____________ .

5. I was able to RESPOND to the presentation as directed

_______________ .

6. I found the website ____________ engaging.

7. In terms of visual appeal and impression, I sound the

website to be ____________ appealing.

8. Please check the boxes of the visual elements that you

found particularly appealing.

9. Overall, I found this website _____________ easy to use.

10. Overall, I found the website design to be __________ .

Responses

as fast as I wanted

pretty fast

pretty slow

frustratingly slow

0

1-2

3-4

right away

after some looking

after a lot of looking

after a wrong turn

right away

after some looking

after a lot of looking

after a wrong turn

right away

after some looking

after a lot of looking

after a wrong turn

very

sort of

not at all

extremely

sort of

not at all

colors

images

menu on left side of page

"Wonder" discussion pages

"Ladder of Prejudice" wall

"Invictus" trailer

Voki avatar frames

incredibly

pretty

sort of

not at all

transparent and noticably elegant

good because I didn't have

to think about it

just okay

a little frustrating

Table 2. Compliation of post-use survey results provided by four respondents.

100%

0%

0%

0%

25%

75%

0%

75%

25%

0%

0%

100%

0%

0%

0%

100%

0%

0%

0%

100%

0%

0%

100%

0%

0%

21%

17%

17%

17%

13%

13%

4%

75%

25%

0%

0%

75%

25%

0%

0%

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

Talk-aloud Script Questions and Prompts

How would you rate your computer

experience on a scalre of 1-10, with 1 being

a complete novice and 10 being an expert

Have you ever participated in an online course of

study?

When you are online, what websites do you use

most, and what do you use them for?

Here is the home page for the website.

What is the title of the unit?

What is its purpose?

What would a student involved in this unit be

thinking about or doing?

(Screen removed.) What did you notice first?

What did you like or dislike?

How would you describe the overall feel and tone?

(Respondent given two tasks: to be able to post a

response to the "Wonder" discussion board and

find a way to respond to the Prezi as directed for

week 1.)

After the tasks, the following questions were asked:

* "How did the ease of completing this task compare

to that of typical web work you have experienced

before?"

* "What did you enjoy about the work you just did?"

* "What was not as enjoyable?"

38

SME Responses

9

No

The Dartmouth (school) website, Facebook,

teacher- and education-related blogs and various websites

like Edutopia. I use them

to communicate with friends and peers; I am always looking

for new teaching ideas. I also shop online for just about

everything.

Responding to Prejudice.

(Respondent reads from the home page.)

They will be thinking about this big topic, writing, and

reading about prejudice.

Visually, I love the design. The simple drawing of the dove

and the colors. The clean look and succinct writing.

Again, the colors and the way they go together. The overall

look and the menu on the left.

Beautiful, welcoming, clear and easy.

(Note: the respondent did a lot more than the two given

tasks due to curiousity about the multimedia elements.)

* This was very easy.

* I liked the real-time modeling in the Prezi (voiceover).

* I liked how the Voki was like taking your teacher home

with you.

* I enjoyed all of it, especially the variety of the sources.

* I enjoyed everything. The only slightly confusing thing

was having to use the back arrow to get back sometimes.

Table 3. Talk-aloud prompts and responses of the SME during observed interaction with the

website.

Discussion

Despite being overwhelmingly positive, the alpha testing results presented in Tables 2 and

3 did point to a few concerns with the website design. The four users who completed the two

tasks independent of the designer quickly confronted the obstacle of privacy settings on the

"Wonder" discussion board housed on an off-site wikipage. Once this was rectified, they were

quickly able to leave a response as requested. This was actually a flaw in the design of the

usability testing, not of the website itself as students will not encounter this difficulty. One user

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE

39

had difficulty getting to the weekly "Wonder" response pages as demonstrated in their response

to survey question three. As a result, the on-screen website directions were changed to make it

very clear what needs to be clicked in order to access them.

Sitting alongside the SME who consented to the talk-aloud testing process yielded more

actionable information. As she read the screen directions for task completion, it became clear

that referents needed to be moved to the same frame as their references in the directions, as she

had to scroll down past the directions more than once to access a button. Further, as she read a

large chunk of on-screen directions, it became obvious that they would be more clear if they

were divided visually. As a result of this test, then, much of the week one page was re-arranged;

the same principles were applied to the other pages as well. During testing it also became

obvious that leaving the website in order to access a survey or a file, sometimes to a new window

and sometimes not, was troublesome. Accordingly, the designer added on-screen information in

a new color, rusty red, briefly stating that the user should use the back arrow to return to the unit

website when appropriate. It is assumed that when a new tab opens, returning to the website will

not prove difficult.

In conclusion, both forms of usability evaluation resulted in actionable information that

should improve the website's functionality for users. Moreover, usability testing results suggest

that the designer's goal of creating an engaging and nonfrustrating web-experience that enhances

the content seems to have been accomplished as evidenced by the results displayed in Table 2.

For example, 100% of users found the website to be "extremely easy" to use and "very

engaging." It can be concluded that, prior to beta testing, the Responding to Prejudice website

exemplifies all of the 5Es--it is efficient, effective, engaging, error-tolerant, and easy to use.