Elements of Journalism Style Guide

advertisement

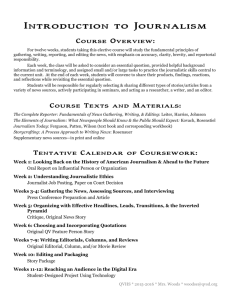

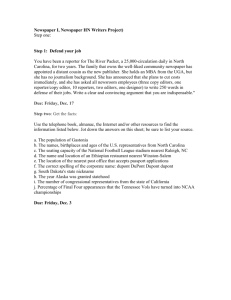

SPRINGFIELD TOWNSHIP HIGH SCHOOL Elements of Journalism A Guide for The Chronicle Frank Vitale IV 10/7/2011 This guide is meant to help student journalists improve their skills by providing a solid foundation for the creation, editing, and distribution of quality articles. Defining News, Finding Stories, and Interviewing Sources What is News? News, simply put, is information about the world around us: people, places, events, or issues. However, newspapers do not report about every person, place, event, or issue that comes to their attention. When attempting to locate a story, the following elements must be considered: Timeliness Readers' Interest (see "Who cares?") Proximity to readership Prominence (how well-known it is) Effects on the Reader Conflict Who Cares? Often, journalists make the mistake of following a story that readers are not interested in. Before pursuing a story, evaluate how your readers will respond and react to it. Avoid those that would elicit a response of "who cares?" or "no duh," as such stories are most likely not worth reporting. Hard, soft, or mushy In the world of journalism, stories are divided into two over-arching categories: hard news and soft news. In The Chronicle, we also have a third category: mushy news. Hard news is strictly facts, and is not intended to entertain or amuse readers. Serious stories, such as reports on crime and stories about building and reconstruction, are considered to be hard news. Hard news most often falls under the jurisdiction of a News Editor. Soft news, on the other hand, is meant to entertain the reader as much as it is meant to inform them. New teacher interviews, student profiles, and reviews (including movie, music, art, or other reviews) are soft news. Soft news is almost always under the realm of Features and Entertainment editors. Mushy news (our name for Tabloid-style news) is really not news at all, but rather articles that have very little if any basis in fact. This kind of story is only used in "April Fool's" issues or the like. Mushy news is always considered Features or Entertainment. Where the News Stories Are Sometimes, stories can be found right in front of you; most of the time, however, finding them will require a bit of digging. A good journalist can find and pursue stories in the most unlikely of places. The easiest way to do this is through tips from other people. These bits of information can help you find a source, which provides trustworthy information for your story. Sources There are two types of sources: primary and secondary. Primary sources are people with firsthand information on the story. Secondary sources, such as reference books, letters, press releases, and informed opinions, are also used to form stories. Generally, it is best to use as many primary sources as possible, and to shy away from any secondary sources. Journalists also frown upon the use of anonymous sources for numerous reasons. The Stress-Test for Sources Not all sources are created equal. Good sources are up-to-date, informed, accurate, and - most importantly - verifiable. A good source is one that can be backed up by other sources. Be wary of sources that cannot be corroborated, as well as any Internet sources. The Local Angle Normally, a student newspaper will want stories to be written with a local angle. A local angle is when the story is written highlighting things of interest or importance to local readers. Any story can be written with a local angle by involving students or community members in the story, either by reporting their opinions or using them as a cited source. Interviewing Sources Interviews are essential to the journalistic process. It is how good journalists get most of their information. After you have found sources, narrow down the list to those few that have the most direct and pertinent information about the story. This will ensure that you get all of the information you need without wasting time gathering repeat information. Requesting an Interview When requesting an interview, it is important to come off as professional as possible, especially if you do not know the source very well. Requesting interviews can either be done in person or via email, but should always include some basic information: your first and last name the name of the newspaper (and the school if the source is not within the building) the topic of the story feasible meeting times, locations, and dates If doing an interview on-the-spot, which is not normally the case, ask if the source has a few minutes to spare and explain the topic of the story before you begin the interview. The Interview Face-to-face interviews are the best form of interviewing, and some editors or advisers may only allow you to interview face-to-face, depending on the story and the source. Interviews should always be scheduled around the source's schedule before your own, and should be at a place that is convenient and safe for both you and the source. About 20-30 minutes of time should be devoted for interviews. Be sure to bring a notebook, pencil, and your questions (see"Writing Interview Questions"). For some stories and in special circumstances, email or online interviews may be acceptable to editors or advisers. The best way to do an online interview is via an online video chat program, such as Skype or Oovoo. After that, online chats and emails can be used. The issue with such text-only forms of communication is that a message can be misinterpreted. If doing an email interview, the source should be asked to provide as much detail and as many clarifying facts as possible. They should also be alerted to the possibility of follow-up questions. A Word About Recording Interviews With voice recorders, camcorders, video cameras, and cell phones, it can be quite tempting to just hit the record button. However, before doing so, make sure that the source knows you are recording the interview and is okay with it. If they are not, you must respect their wishes and put away the recorder. At any time, they have the right to request that the recorder be turned off. Often, chat, email, and online video conversations are automatically saved. If doing such an interview, remind the source that this is the case. This is the online equivalent of using a voice recorder, and should be treated as such. Writing Interview Questions The basis of any interview should be finding out about the basic facts of the story, otherwise known as the who, what, where, when, why, and how of the story. You can elaborate on these in secondary questions. Be sure that your questions are clear, simple, and concise. Make sure the questions are open-ended, and that they make your sources think. Be ready to ask follow-up or clarifying questions if need be. Do not ask controversial questions or questions that may throw the source off guard; if you are unsure, check your questions with your editor or adviser before the interview. Works Cited “Journalism.” MediaCollege.com. Wavelength Media, n.d. Web. 19 Sept. 2011. <http://www.mediacollege.com/journalism/interviews/>. Levin, Mark. EXp3 - Journalism: A Handbook for Journalists. 1952. Lincolnwood, Illinois, USA: National Textbook Company, 1999. Print. Pavlik, John V. Journalism and New Media. New York: Columbia U., 2001. Print. “Practical Tips for Finding a Focus When Writing.” Poynter.org. The Poynter Inst., 2011. Web. 19 Sept. 2011. <http://www.poynter.org/how-tos/newsgathering-storytelling/writing-tools/ 141685/live-chat-today-practical-tips-for-finding-a-focus-when-writing/>. Writing the Article: Leads, Quotes, and Organization Questions have been asked, interviews have been conducted, and information has been obtained. Now comes the task that is often seen to be the most daunting: writing the high-quality article that will garner the readers' attention. Leads The lead is the beginning, and most important, part of an article. It sets the tone for the entire article, and often determines the length and breadth of the article itself. The lead draws a reader into the story, and keeps them interested in the information. Leads can be anywhere from 1 to 3 sentences long. What Makes a Good Lead A good lead has three crucial components: 1. Sets an appropriate mood and tone for the story 2. Draws in the reader 3. Gives some information into the subject of the article itself A good journalist will ensure that their lead fits all of these criteria, and will keep these criteria in mind when choosing angles to write the story through. Consider the story you are writing. Does it require a serious tone, or can it be written from a humorous point of view? Does it require a real attention-grabbing lead, or is it interesting enough to draw the reader in without an unconventional opening? Is there information that the reader should know by the end of the first three lines of the article? Use the answers to these questions to help formulate your lead. Types of Leads There are multiple types of leads, all with a specific purpose, style, mood, tone, color, breadth, depth, and length. All of these aspects must be considered when choosing what kind of lead to write. The following are multiple types of leads, with relevant but fictional headlines. Summary Lead o Summary leads contain the essentials of the article: the who, what where, when, why, and how. They are normally shorter than 40-50 words. They are the typical journalist's lead, as seen in many national and local newspapers. High School Assistant Principal Dr. Melanie-Jo McCarthy, along with Principal Gregory Pucket and Assistant Principal Ryan Johnston, kicked off the school's No Place for Hate initiative on Friday, September 9th, with an assembly led by psychologist Michael Fowlin. Single-Item Lead o Focusing on a single aspect of the story, this lead gives a greater punch and excites the reader. Springfield's Lady Spartan Basketball Team won at Districts. Delayed Identification Lead o Often, a story might be very interesting, but the subject may not be very well known. Using a delayed identification lead, journalists can draw readers into a story without initially identifying who the story is about. Over the summer, the District welcomed a new Human Resources Director to their administrative staff. Analogy Lead o A sure-fire way to get the readers' attention is to compare the story at hand with something they are familiar with. This comparison must be fair, accurate, and unbiased. The Board of School Directors proposed a budget at Tuesday's meeting that proposes cuts that pale in comparison to cutbacks made by surrounding school districts. Amazing Fact Lead o This lead uses a surprising, unknown, and related fact to catch the readers' attention. Springfield Township High School is among the top ten schools in the tri-county area, according to a recently published report. Opposite Lead o Present one viewpoint, and then an opposing viewpoint, to open the story. A new study out from the University of Pennsylvania claims that the use of cell phones as learning devices in school is not a practical alternative to notebook or tablet computers. Springfield Township High School disagrees. Quote Quotations from relevant primary and secondary sources add new depth to an otherwise flat article, and help present multiple points of view without appearing biased. They also help break up ideas and transition from one thought to another within the article. However, quotes can be difficult to incorporate into an article, depending on the story and the content of the quote. Incorporating Quotes In articles, quotations are most often incorporated after an idea has been fully fleshed out and explained. In this instance, the quotation serves to add another point of view to the presented idea, or to provide relevant commentary on the issue. Often, such quotes will appear at the end of a paragraph, or will serve as their own separate paragraph at the end of a series of connected paragraphs on the subject. Quotes can also be used to introduce ideas; in this case, quotations are placed at the beginning of a paragraph or set of paragraphs. Introductory quotes are normally unbiased, or are expert opinions. Note that quotations should never serve as the lead of an article. Separate Quotes In some instances, quotations may be compiled from numerous sources that are all presented in a section separate from the article itself. Often, such quotes are answering a single question asked to all of the sources. Such a compilation should include opinions from all sides of an issue, and should include student, teacher, staff, and administrative sources if relevant. This section may be laid out in an eyeappeasing style, but should show favor for any one side or argument. Warnings about Quotations When using quotations, some issues may arise. When transcribing quotations from audio or video recordings, mistakes may occur that change the meaning of the excerpt. This error can also happen if quotes are being recorded by hand. Journalists must take advanced precautions with such quotations, especially if the recording is difficult to understand. If unsure about a certain word or phrase in a recording, consult the Editor-in-Chief and advisers, or reconfirm the quotation directly with the source. Quotations should always be attributed to a specific source. This attribution should be incorporated into the article itself, and should contain any relevant title of the source, such as Director of Admissions, Superintendent, Principal, Department Coordinator, and the like. Staff members and advisers for The Chronicle should never be quoted in an article, as this is a conflict of interest. Organization The structure of an article helps not only to keep the information organized, but also to keep the readers' attention throughout the story. It is best for a single issue to contain articles that utilize varying structures to keep the reader enthused. There are three main structure styles, each with their own advantages, disadvantages, and usages. The Inverted Pyramid Style This style is the most commonly used structure style in newspapers. It is the best structure for hard news articles. It presents the most pertinent facts and information in the first few paragraphs of the article, with each new paragraph presenting points that are less and less important. An example follows below: The Martini-Glass or Wine-Glass Style The Martini-Glass or Wine-Glass Style is very similar to the Inverted Pyramid Style, but is better suited for stories that rely on a specific chronology. It begins by presenting the most important facts in the first few paragraphs, from most to least important, and then transitions into a chronological explanation of the events. The article ends with a surprising fact or afterthought that succinctly ends the story. An example follows below: Kabob Style Better for soft news and anecdotal articles, this structure uses a story to transition into and out of a general discussion of the topic, with a clarifying paragraph thrown in the mix. An example follows below: Works Cited Grabowski, Mark. “How to Write Good Story Leads.” CubReporters.com. N.p., 2010. Web. 27 Sept. 2011. <http://cubreporters.org/leads.html>. - - -. “Journalism Story Structure.” CubReporters.com. N.p., 2010. Web. 27 Sept. 2011. <http://journalism-education.cubreporters.org/2010/08/journalism-story structure.html>. Hall, Jim. “The Structure of the News Story.” Beginning Reporting. Virginia Commonwealth U, n.d. Web. 27 Sept. 2011. <http://www.courses.vcu.edu/ENG-jeh/BeginningReporting/Writing/ storystructure.htm>. Article Types: News, Features, Sports, and Editorials In all professional newspapers, writers are assigned a certain subject area to cover, and report to the editor of their section. In The Chronicle, there are 4 main sections: News, Features, Sports, and Entertainment. In The Chronicle, journalists are what section their story falls under, and what editor to report to. That editor is responsible for the editing, placing, and layout of their section. News Section The News Section is led by the News Editor. These articles are almost always hard news, and are often placed on the front cover, as well as throughout the issue. They should be serious in nature, and should be at least 650 words in length. They often use quotations from multiple sources, as well as pictures or other relevant graphics. News articles should represent the majority of the articles published in the paper for any given issue, with the exception of the April Fools' Issue and Graduation Issue. Features Section The Features Section is led by the Features Editor, and includes both hard and soft news pieces that normally are run with other articles of a similar theme. For example, a feature might be run about Homecoming Week. This would include hard news articles about the dance, soft news articles about the bonfire and tailgate, and numerous pictures. This provides a natural balance for an interesting spread. Features are normally spread across two adjoining pages. Features may be any length. Articles from other sections may also fall under the jurisdiction of the Features Section if subject permits: an article done by the Sports Section about the Homecoming football game would be considered a features article if put in the homecoming spread. Sports Section The Sports Section reports to the Sports Editor, and includes articles and reviews of sports teams, whether they be school, regional, national, or international teams. The Sports Section will almost always use pictures to supplement their articles. Sports articles should be around 400-800 words, unless a spread is being created, in which case they may be extended further. Sports articles, like all other articles, should not be written by a journalist who has a specific tie to the team (ie. player, manager, coach, etc.) as this is a conflict of interest. Entertainment Section The Entertainment Section is under the jurisdiction of the Entertainment Editor. This section includes comics, reviews (including music, movie, and video game reviews), and "mushy news" articles (see "Defining News"). Comics should be submitted as digital TIFF, JPEG, or GIF files. Reviews should be anywhere from 400-700 words. All reviews and comics should be school appropriate. The rule of thumb is that if you have to ask if it is appropriate, it probably isn't. Reviewers should avoid writing critiques on movies/songs/etc. with expletives in the title. Comics may not be about a particular student, faculty member, administrator, or other person without expressed approval by said person; even in this instance, comics may not be hurtful or demeaning to the person in any way, shape, or form. Other Articles Aside from the article types listed in the above sections, other types of stories may be reported. Opinion and editorial pieces fall under the jurisdiction of the Associate Editor and the Editor-in-Chief. Articles written by outside or guest writers fall under the jurisdiction of the Editor-in-Chief unless determined otherwise. Articles submitted by Student Council or other student organizations are under the control of the Editor-in-Chief. If there is a question as to what editor an article falls under, the Editor-in-Chief and the advisers should be consulted. Works Cited Levin, Mark. EXp3 - Journalism: A Handbook for Journalists. 1952. Lincolnwood, Illinois, USA: National Textbook Company, 1999. Print. “Module One - Print Journalism.” Journalism Studies 20. Saskatchewan Schools and School Div., 2005. Web. 19 Sept. 2011. <http://www.saskschools.ca/curr_content/journalism20/print_journalism/ print_journalism_index.htm>. Editing and Proofreading One articles have been turned in, the process of editing and proofreading begins. This is an essential part in creating a well-written paper that lacks mistakes and misprints. The Difference between Editing and Proofreading When an article is turned in, it is printed out through a word processor. This is often called a copy. Editing, also known as copy-editing, is the correction of copies. When a copy is placed in the layout, it is referred to as a proof. Proofreading is the process of correcting errors in proofs before being sent to print. Editing Editing is the often the first line of defense against spelling, mechanical, and factual errors within a story. Before an article is ever printed out, it should be run through spell check to catch the majority of mistakes. Once printed, all of the names, dates, quotes and places in the copy should be checked for accuracy and correctness. Passive voice should be eliminated wherever possible. First and second person should be changed to third person. Active tense verbs should be used as well. The story's angle should be checked to ensure that it will appeal to the audience of the article. A stylebook for the paper should be referenced if any questions arise about the copy's writing. If the organization is flawed, it should be changed so the article reads better. The author of a copy should never be the only one to edit the copy if at all possible. Proofreading Proofreading, unlike editing, does not involve double-checking facts and reorganizing the copy. It involves catching mistakes not found in editing, as well as those introduced when the copy was placed into the layout. Proofreaders should check for punctuation errors, tabulation errors, cut-offs with copies, missing indents, extra spaces, and errors in headlines and cutlines. Widows, short lines at the end of a paragraph appearing at the top of a column, and orphans, a short word sitting on a line by itself, should be eliminated by repositioning. Unlike editing, authors should never read proofs of their own work, as this is the best way for mistakes to be overlooked. Apply Edits and Saving Copies and Proofs Once edits have been found in copies and issues have been identified in a proof, the changes must be made to the master file. Again, edits should be made to the copies by the author. The author has the right to refuse to make any changes that change the voice of the article; however, they must make any grammatical or spelling changes found. Once proofs have been looked over, any changes should be made by either the editor in charge of the section, or the Editor-in-Chief, depending on the amount of edits and the deadline until printing. The number of the draft of the copy or proof, or the date when the copy or proof was looked over, should be marked on the files. The hard copies of both the copies and proofs should be kept. This is to ensure not only that the edits are documented, but also that the edits are available for use if a file becomes corrupted later on in the editing process. The Great Editing Balancing Act One of the age-old struggles of editors and proofreaders is making sure that the voice of the article or its sentences is not changed. This can often be a difficult task, as an edit that seems fine to an editor may be rejected or disliked by the author. If possible, the author should be the person to apply the edits to the copy, so that any change in voice is avoided. If this is not possible, the author should approve the edited copy before it is placed and printed. Well, You Messed Up. Now What? If a mistake - especially a factual mistake or a spelling mistake for someone's name - slips through editing and proofing, a retraction should be printed. This should be on the same page as the masthead, and should state what was printed, what the correction is, and when/what issue the article was published. Works Cited Grabowski, Mark. “The Final Edits: 5 Things to Do Before Submitting Your Story.” CubReporters.org. N.p., 2010. Web. 5 Oct. 2011. <http://journalism-education.cubreporters.org/2010/08/final-edit-fivethings-to-do-before.html>. Levin, Mark. EXp3 - Journalism: A Handbook for Journalists. 1952. Lincolnwood, Illinois, USA: National Textbook Company, 1999. Print. Distribution and Reflection of Product Distribution Now that the paper has been printed and delivered to the school, it needs to be distributed. This can be confusing process, and can be difficult to navigate for someone not used to the process. Different methods of distribution are used to deliver the paper to different audiences. Papers meant for students should be placed in homerooms, the main office, the library, and other common, high-traffic areas. Papers should be placed in faculty mailboxes as well. Copies of the newspaper should be handdelivered to the high school administration. Papers should also be supplied to the district's administration as well as the school board by way of the district secretary in the Administration Building. Reflection of the Product After the paper has been in circulation for a week or so, the staff should sit down to discuss the strong points and weak points of the paper. Special attention should be paid to the comments made about the paper, whether it is from submitted comments or general remarks overheard in the halls. Flaws in the issue should be noted, and discussion should occur on how to avoid such errors in the future. Distribution methods should also be analyzed regularly for effectiveness. Decisions should be made on where to place the issue and how many to print for each run. Works Cited Levin, Mark. EXp3 - Journalism: A Handbook for Journalists. 1952. Lincolnwood, Illinois, USA: National Textbook Company, 1999. Print. “Newspaper Distribution.” HowStuffWorks. Discovery, 2011. Web. 7 Oct. 2011. <http://people.howstuffworks.com/newspaper5.htm>.